What Painting Is “A Truly Original Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

Alchemical Journey Into the Divine in Victorian Fairy Tales

Studia Religiologica 51 (1) 2018, s. 33–45 doi:10.4467/20844077SR.18.003.9492 www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Religiologica Alchemical Journey into the Divine in Victorian Fairy Tales Emilia Wieliczko-Paprota https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8662-6490 Institute of Polish Language and Literature University of Gdańsk [email protected] Abstract This article demonstrates the importance of alchemical symbolism in Victorian fairy tales. Contrary to Jungian analysts who conceived alchemy as forgotten knowledge, this study shows the vivid tra- dition of alchemical symbolism in Victorian literature. This work takes the readers through the first stage of the alchemical opus reflected in fairy tale symbols, explains the psychological and spiritual purposes of alchemy and helps them to understand the Victorian visions of mystical transforma- tion. It emphasises the importance of spirituality in Victorian times and accounts for the similarity between Victorian and alchemical paths of transformation of the self. Keywords: fairy tales, mysticism, alchemy, subconsciousness, psyche Słowa kluczowe: bajki, mistyka, alchemia, podświadomość, psyche Victorian interest in alchemical science Nineteenth-century fantasy fiction derived its form from a different type of inspira- tion than modern fantasy fiction. As Michel Foucault accurately noted, regarding Flaubert’s imagination, nineteenth-century fantasy was more erudite than imagina- tive: “This domain of phantasms is no longer the night, the sleep of reason, or the uncertain void that stands before desire, but, on the contrary, wakefulness, untir- ing attention, zealous erudition, and constant vigilance.”1 Although, as we will see, Victorian fairy tales originate in the subconsciousness, the inspiration for symbolic 1 M. Foucault, Fantasia of the Library, [in:] Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, D.F. -

Hints and Tips - Painting 28Mm Armies

Hints and Tips - Painting 28mm Armies Good results in less than 45 minutes per figure. By Michael Farnworth Original January 2007, Updated January 2008 Wargamers need to put several figures on a table before they can play. Even a small skirmish game needs fifty figures to form two opposing sides. Painting Guides often show you how to create a masterpiece in a few hours. However a few hours per figure, translates into several months before a game is playable. There are few guides to help you to paint a large number of figures to a reasonable standard in a relatively short time. I paint and base a 28mm figure in about 45 minutes. WW2 soldiers take less time but usually medieval soldiers and Vikings take a little longer. I paint about 350 figures per year. Although the standard is not stunning, they do look presentable on a table. To paint large quantities of figures in a relatively short time requires a little bit of a production engineering mentality. Choice of materials is important as is choice of tools. However, the best paints and the best tools do not get the job done. A well thought out sequence and a sensible batch size makes the job quicker. As a last point, psychology is important. Figure painting is a hobby. It should be fun. Boredom means that projects do not get finished. Unfinished projects and a growing lead pile is a common frustration. I have developed my technique to maximise the sense of achievement early on in the process. I find that this helps to carry me through to the end result – a finished army. -

Download Full Book

Respectable Folly Garrett, Clarke Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Garrett, Clarke. Respectable Folly: Millenarians and the French Revolution in France and England. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.67841. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/67841 [ Access provided at 2 Oct 2021 03:07 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. HOPKINS OPEN PUBLISHING ENCORE EDITIONS Clarke Garrett Respectable Folly Millenarians and the French Revolution in France and England Open access edition supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. © 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press Published 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. CC BY-NC-ND ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3177-2 (open access) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3177-7 (open access) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3175-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3175-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3176-5 (electronic) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3176-9 (electronic) This page supersedes the copyright page included in the original publication of this work. Respectable Folly RESPECTABLE FOLLY M illenarians and the French Revolution in France and England 4- Clarke Garrett The Johns Hopkins University Press BALTIMORE & LONDON This book has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of the Andrew W. -

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library VOLUME 42 Medieval and Early Modern Science Editors J.M.M.H. Thijssen, Radboud University Nijmegen C.H. Lüthy, Radboud University Nijmegen Editorial Consultants Joël Biard, University of Tours Simo Knuuttila, University of Helsinki Jürgen Renn, Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science Theo Verbeek, University of Utrecht VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hsml Verse and Transmutation A Corpus of Middle English Alchemical Poetry (Critical Editions and Studies) By Anke Timmermann LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 On the cover: Oswald Croll, La Royalle Chymie (Lyons: Pierre Drobet, 1627). Title page (detail). Roy G. Neville Historical Chemical Library, Chemical Heritage Foundation. Photo by James R. Voelkel. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Timmermann, Anke. Verse and transmutation : a corpus of Middle English alchemical poetry (critical editions and studies) / by Anke Timmermann. pages cm. – (History of Science and Medicine Library ; Volume 42) (Medieval and Early Modern Science ; Volume 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback : acid-free paper) – ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) 1. Alchemy–Sources. 2. Manuscripts, English (Middle) I. Title. QD26.T63 2013 540.1'12–dc23 2013027820 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1872-0684 ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

Painting in Acrylic and Oil Instructor: Thomas J

Painting in Acrylic and Oil Instructor: Thomas J. Legaspi [email protected] All materials can be purchased at art stores such as Artist and Craftsman or Blick or easily ordered online. We do not endorse one store over the other. Please feel free to bring similar supplies you already have rather than buying new supplies. We will go over this list in the first class and I will have supplies that you can use in the first class if you are uncertain of what exactly to buy. Paint The best brand for your dollar is Gamblin. Other good brands include Winsor and Newton, Blick and Vasari. Old Holland is a great brand but quite expensive. For this course you can purchase oil, acrylic or both. Recommended Paints: ● Burnt Umber ● Burnt Sienna or Transparent Red Oxide or Red Earth ● Ultramarine Blue ● Cadmium Yellow Light (contains cadmium which a hazardous material) or Cadmium Yellow HUE (contains no actual cadmium) or Hansa Yellow Light (contains no actual cadmium) ● Cadmium Red Light (contains cadmium which is a hazardous material) or Cadmium Red HUE (contains no actual cadmium) or Vermillion (contains no actual cadmium) or Naphthol Red (contains no actual cadmium) ● Yellow Ochre ● Flake White Replacement made by Gamblin (when painting flesh this white will retain your colors more vibrantly than Titanium White) ● Titanium White ● Phthalo Green or Viridian Green ● Alizarin Crimson Optional Paints: ● Cerulean Blue ● Cobalt Blue ● Brown Pink ● Naples Yellow Brushes Please purchase 4-5 brushes for this class. The type of brush you use should be based on the type of painting style you want to achieve. -

Magnes: Der Magnetstein Und Der Magnetismus in Den Wissenschaften Der Frühen Neuzeit Mittellateinische Studien Und Texte

Magnes: Der Magnetstein und der Magnetismus in den Wissenschaften der Frühen Neuzeit Mittellateinische Studien und Texte Editor Thomas Haye (Zentrum für Mittelalter- und Frühneuzeitforschung, Universität Göttingen) Founding Editor Paul Gerhard Schmidt (†) (Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg) volume 53 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/mits Magnes Der Magnetstein und der Magnetismus in den Wissenschaften der Frühen Neuzeit von Christoph Sander LEIDEN | BOSTON Zugl.: Berlin, Technische Universität, Diss., 2019 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Sander, Christoph, author. Title: Magnes : der Magnetstein und der Magnetismus in den Wissenschaften der Frühen Neuzeit / von Christoph Sander. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Mittellateinische studien und texte, 0076-9754 ; volume 53 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019053092 (print) | LCCN 2019053093 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004419261 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004419414 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Magnetism–History–16th century. | Magnetism–History–17th century. Classification: LCC QC751 .S26 2020 (print) | LCC QC751 (ebook) | DDC 538.409/031–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019053092 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019053093 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill‑typeface. ISSN 0076-9754 ISBN 978-90-04-41926-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-41941-4 (e-book) Copyright 2020 by Christoph Sander. Published by Koninklijke -

The Philosopher's Stone

The Philosopher’s Stone Dennis William Hauck, Ph.D., FRC Dennis William Hauck is the Project Curator of the new Alchemy Museum, to be built at Rosicrucian Park in San Jose, California. He is an author and alchemist working to facilitate personal and planetary transformation through the application of the ancient principles of alchemy. Frater Hauck has translated a number of important alchemy manuscripts dating back to the fourteenth century and has published dozens of books on the subject. He is the founder of the International Alchemy Conference (AlchemyConference.com), an instructor in alchemy (AlchemyStudy.com), and is president of the International Alchemy Guild (AlchemyGuild. org). His websites are AlchemyLab.com and DWHauck.com. Frater Hauck was a presenter at the “Hidden in Plain Sight” esoteric conference held at Rosicrucian Park. His paper based on that presentation entitled “Materia Prima: The Nature of the First Matter in the Esoteric and Scientific Traditions” can be found in Volume 8 of the Rose+Croix Journal - http://rosecroixjournal.org/issues/2011/articles/vol8_72_88_hauck.pdf. he Philosopher’s Stone was the base metal into incorruptible gold, it could key to success in alchemy and similarly transform humans from mortal Thad many uses. Not only could (corruptible) beings into immortal (incor- it instantly transmute any metal into ruptible) beings. gold, but it was the alkahest or universal However, it is important to remember solvent, which dissolved every substance that the Stone was not just a philosophical immersed in it and immediately extracted possibility or symbol to alchemists. Both its Quintessence or active essence. The Eastern and Western alchemists believed it Stone was also used in the preparation was a tangible physical object they could of the Grand Elixir and aurum potabile create in their laboratories. -

Lost Knowledge of the Imagination

Praise for Gary Lachman “The Lost Knowledge of the Imagination rejoins the parted Red Sea of modern intellect, demonstrating how rationalism and esotericism are not divided forces but necessary complements and parts of a whole in the human wish for understanding. More still, he elevates the relevancy of spiritual philosophies that we are apt to short-shrift, from Crowley to positive thinking, and issues a warning: If thoughts are causative, it is all the more vital that we, the thinkers, know ourselves.” Mitch Horowitz, PEN Award-winning author of Occult America and One Simple Idea: How Positive Thinking Reshaped Modern Life “A cracking author.” Lynn Picknett, Magonia Review of Books “Lachman is an easy to read author yet has a near encyclopaedic knowledge of esotericism and is hence able to offer many different perspectives on the subject at hand.” Living Traditions magazine “Lachman’s sympathetic, but not uncritical, account of [Rudolf Steiner’s] life is to be recommended to anyone who wishes to be better informed about this gifted and remarkable man.” Kevin Tingay, The Christian Parapsychologist “Lachman challenges many contemporary theories by reinserting a sense of the spiritual back into the discussion” Leonard Schlain, author of The Alphabet Versus the Goddess “Lachman’s depth of reading and research are admirable.” Scientific and Medical Network Review For Kathleen Raine (1908-2003), who showed the way Contents Title Page Dedication Acknowledgments Chapter One: A Different Kind of Knowing Chapter Two: A Look Inside the World Chapter Three: The Knower and the Known Chapter Four: The Way Within Chapter Five: The Learning of the Imagination Chapter Six: The Responsible Imagination Further Reading Also by Gary Lachman Copyright Acknowledgments My thanks go to my editor Christopher Moore for taking on the project and to the staff of the British Library where most of the research was done. -

A Lexicon of Alchemy

A Lexicon of Alchemy by Martin Rulandus the Elder Translated by Arthur E. Waite John M. Watkins London 1893 / 1964 (250 Copies) A Lexicon of Alchemy or Alchemical Dictionary Containing a full and plain explanation of all obscure words, Hermetic subjects, and arcane phrases of Paracelsus. by Martin Rulandus Philosopher, Doctor, and Private Physician to the August Person of the Emperor. [With the Privilege of His majesty the Emperor for the space of ten years] By the care and expense of Zachariah Palthenus, Bookseller, in the Free Republic of Frankfurt. 1612 PREFACE To the Most Reverend and Most Serene Prince and Lord, The Lord Henry JULIUS, Bishop of Halberstadt, Duke of Brunswick, and Burgrave of Luna; His Lordship’s mos devout and humble servant wishes Health and Peace. In the deep considerations of the Hermetic and Paracelsian writings, that has well-nigh come to pass which of old overtook the Sons of Shem at the building of the Tower of Babel. For these, carried away by vainglory, with audacious foolhardiness to rear up a vast pile into heaven, so to secure unto themselves an immortal name, but, disordered by a confusion and multiplicity of barbarous tongues, were ingloriously forced. In like manner, the searchers of Hermetic works, deterred by the obscurity of the terms which are met with in so many places, and by the difficulty of interpreting the hieroglyphs, hold the most noble art in contempt; while others, desiring to penetrate by main force into the mysteries of the terms and subjects, endeavour to tear away the concealed truth from the folds of its coverings, but bestow all their trouble in vain, and have only the reward of the children of Shem for their incredible pain and labour. -

Alchemy Ancient and Modern

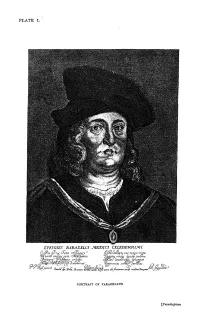

PLATE I. EFFIGIES HlPJ^SELCr JWEDlCI PORTRAIT OF PARACELSUS [Frontispiece ALCHEMY : ANCIENT AND MODERN BEING A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE ALCHEMISTIC DOC- TRINES, AND THEIR RELATIONS, TO MYSTICISM ON THE ONE HAND, AND TO RECENT DISCOVERIES IN HAND TOGETHER PHYSICAL SCIENCE ON THE OTHER ; WITH SOME PARTICULARS REGARDING THE LIVES AND TEACHINGS OF THE MOST NOTED ALCHEMISTS BY H. STANLEY REDGROVE, B.Sc. (Lond.), F.C.S. AUTHOR OF "ON THE CALCULATION OF THERMO-CHEMICAL CONSTANTS," " MATTER, SPIRIT AND THE COSMOS," ETC, WITH 16 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS SECOND AND REVISED EDITION LONDON WILLIAM RIDER & SON, LTD. 8 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.G. 4 1922 First published . IQH Second Edition . , . 1922 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION IT is exceedingly gratifying to me that a second edition of this book should be called for. But still more welcome is the change in the attitude of the educated world towards the old-time alchemists and their theories which has taken place during the past few years. The theory of the origin of Alchemy put forward in I has led to considerable discussion but Chapter ; whilst this theory has met with general acceptance, some of its earlier critics took it as implying far more than is actually the case* As a result of further research my conviction of its truth has become more fully confirmed, and in my recent work entitled " Bygone Beliefs (Rider, 1920), under the title of The Quest of the Philosophers Stone," I have found it possible to adduce further evidence in this connec tion. At the same time, whilst I became increasingly convinced that the main alchemistic hypotheses were drawn from the domain of mystical theology and applied to physics and chemistry by way of analogy, it also became evident to me that the crude physiology of bygone ages and remnants of the old phallic faith formed a further and subsidiary source of alchemistic theory. -

A Short Course in Forgetting Chemistry

[This is from What Painting Is (New York: Routledge, 1998). This was originally posted on www.jameselkins.com. This version is unillustrated: some illustrations are on the website. Some alchemical symbols have dropped out of this file. See the website for context, other material from the book, and for contact information for the author. (September 2009).] 1 A short course in forgetting chemistry Painting is alchemy. Its materials are worked without knowledge of their properties, by blind experiment, by the feel of the paint. A painter knows what to do by the tug of the brush as it pulls through a mixture of oils, and by the look of colored slurries on the palette. Drawing is a matter of touch: the pressure of the charcoal on the slightly yielding paper, the sticky slip of the oil crayon between the fingers. Artists become expert in distinguishing between degrees of gloss and wetness—and they do so without knowing how they do it, or how chemicals create their effects. Monet’s paintings are a case in point. They seem especially simple to many people, as if Monet were the master of certain moods—of moist bluish twilight or candent yellow beaches— but nothing more: as if he had no sense that painting could be anything but a method for fixing light onto canvas. In his singleminded pursuit of the grain and feel of light, he seems to forget who he is, and who he is painting. He has only a weak attachment to people, and he treats the figures who stray into his pictures as if they were colored dolls instead of friends and relatives.i Instead his attention is riveted to the blurry shapes that come forward through the imperfect atmosphere, and on the shifting tints of light that somehow congeal into meadows and oceans and haystacks.