The Intellectual and Social Declines of Alchemy and Astrology, Circa 1650-1720

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

Notes on Contributors

Notes on Contributors Giuseppe Bezza teaches the history of science and technology at Ravenna (University of Bologna). He has written a number of essays on the history of astrology. He is the author of Commento al primo libro della Tetrabiblos di Claudio Tolemeo (Milan, 1991), Arcana Mundi. Antologia del pensiero astrologico classico (Milan, 1995) and Précis d’historiographie de l’astrologie: Babylone, Égypte, Grèce (Turnhout, 2003). Joseph Crane studied philosophy at Brandeis and has professional training as a psychotherapist. He has practiced astrology and taught astrological and consulting skills since the late 1980s. He began learning traditional astrology in the early 1990s and since then has brought it into his teaching and consulting practice. He lectures on ancient and modern astrological techniques as well as connecting astrology with works of literature and philosophy. He is the author of Astrological Roots: The Hellenistic Tradition (Bournemouth, 2007), a presentation of Hellenistic astrology to modern astrologers, and A Practical Guide to Traditional Astrology (Reston, VA, 1997/2006). Website: www.astrologyinstitute.com. Susanne Denningmann studied Classics and Philosophy at the University of Münster. From 2000 to 2003 she was a research assistant at the collaborative research centre, Functions of Religion in Ancient Near Eastern Societies, supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG), where she focussed on ancient astrology. She received her PhD in Classics and Philosophy in 2004 at the University of Münster. The subject of her thesis was the astrological doctrine of doryphory, published in 2005 as Die astrologische Lehre der Doryphorie. Eine soziomorphe Metapher in der antiken Planetenastrologie (Beiträge zur Altertumskunde, 214). -

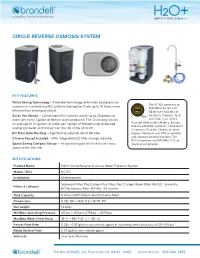

Circle Reverse Osmosis System

CIRCLE REVERSE OSMOSIS SYSTEM KEY FEATURES Water Saving Technology – Patented technology eliminates backpressure The RC100 conforms to common in conventional RO systems making the Circle up to 10 times more NSF/ANSI 42, 53 and efficient than existing products. 58 for the reduction of Saves You Money – Conventional RO systems waste up to 24 gallons of Aesthetic Chlorine, Taste water per every 1 gallon of filtered water produced. The Circle only wastes and Odor, Cyst, VOCs, an average of 2.1 gallons of water per 1 gallon of filtered water produced, Fluoride, Pentavalent Arsenic, Barium, Radium 226/228, Cadmium, Hexavalent saving you water and money over the life of the product!. Chromium, Trivalent Chromium, Lead, RO Filter Auto Flushing – Significantly extends life of RO filter. Copper, Selenium and TDS as verified Chrome Faucet Included – With integrated LED filter change indicator. and substantiated by test data. The RC100 conforms to NSF/ANSI 372 for Space Saving Compact Design – Integrated rapid refill tank means more low lead compliance. space under the sink. SPECIFICATIONS Product Name H2O+ Circle Reverse Osmosis Water Filtration System Model / SKU RC100 Installation Undercounter Sediment Filter, Pre-Carbon Plus Filter, Post Carbon Block Filter (RF-20): 6 months Filters & Lifespan RO Membrane Filter (RF-40): 24 months Tank Capacity 6 Liters (refills fully in less than one hour) Dimensions 9.25” (W) x 16.5” (H) x 13.75” (D) Net weight 14.6 lbs Min/Max Operating Pressure 40 psi – 120 psi (275Kpa – 827Kpa) Min/Max Water Feed Temp 41º F – 95º F (5º C – 35º C) Faucet Flow Rate 0.26 – 0.37 gallons per minute (gpm) at incoming water pressure of 20–100 psi Rated Service Flow 0.07 gallons per minute (gpm) Warranty One Year Warranty PO Box 470085, San Francisco CA, 94147–0085 brondell.com 888-542-3355. -

Bull. Hist. Chem. 13- 14 (1992-93)

ll. t. Ch. 13 - 14 (2 2 tr nnd p t Ar n lt nftr, vd lfr, th trdtnl prnpl f ltn r ldf qd nn ft n pr plnr nd fx vlttn, tn, rprntn "ttr." S " xt Alh", rfrn prnd fr t rrptn." , pp. 66, 886. 25. Ibid., p. 68: "... prpr & xt lnd n pr 4. W. n, "tn Clavis Str Key," Isis,1987, tll t n ..." 78, 644. 26. W. n, The "Summa perfectionis" of pseudo-Geber, 46. hllth, Introitus apertus, BCC, II, 66, "... lphr xtr dn, , pp. 42. n ..." 2. l, "tn Alht," rfrn , pp. 224. 4. frn 4, pp. 24. 28. [Ern hllth,] Sir George Ripley's Epistle to King 48. bb, Foundations , rfrn , p. 28. Edward Unfolded, MS. Gl Unvrt, rn 8, pp. 80, 4. l, " xt Alh", rfrn , p. 64. p. 0. bb, Foundations, rfrn , pp. 22222. 2. MS. rn 8, p. Cf. l Philalethes,Introitusapertus, . Wtfll, Never at Rest, rfrn 8, p. 8. in Bibliotheca chemica curiosa, n Mnt, rfrn 2, l. II, p. 2. r t ll b fl t v bth tn prphr 664. (Cbrd Unvrt brr, Kn MS. 0, f. 22r nd th 30. Ibid., MS. rn 8, pp. 2. rnl (hllth, Introitus apertus, in Bibliotheca chemica curi- 31. Ibid. osa, l. II, p. 66: 32. Ibid., pp. 6. Newton: h t trr prptr ltn , t 33. Ibid. nrl trx prptr nrl n p ltntr, t 4. l, "tn Alht," rfrn , p. 20. tn r vltl, t l [lphr] n tr rvlvntr . [Ern hllth,] Sir George Riplye' s Epistle to King ntnt n ntr , d ntr tt t & trrn d Edward Unfolded, n Chymical, Medicinal, and Chyrurgical AD- prf llnt. -

Sedimentation and Clarification Sedimentation Is the Next Step in Conventional Filtration Plants

Sedimentation and Clarification Sedimentation is the next step in conventional filtration plants. (Direct filtration plants omit this step.) The purpose of sedimentation is to enhance the filtration process by removing particulates. Sedimentation is the process by which suspended particles are removed from the water by means of gravity or separation. In the sedimentation process, the water passes through a relatively quiet and still basin. In these conditions, the floc particles settle to the bottom of the basin, while “clear” water passes out of the basin over an effluent baffle or weir. Figure 7-5 illustrates a typical rectangular sedimentation basin. The solids collect on the basin bottom and are removed by a mechanical “sludge collection” device. As shown in Figure 7-6, the sludge collection device scrapes the solids (sludge) to a collection point within the basin from which it is pumped to disposal or to a sludge treatment process. Sedimentation involves one or more basins, called “clarifiers.” Clarifiers are relatively large open tanks that are either circular or rectangular in shape. In properly designed clarifiers, the velocity of the water is reduced so that gravity is the predominant force acting on the water/solids suspension. The key factor in this process is speed. The rate at which a floc particle drops out of the water has to be faster than the rate at which the water flows from the tank’s inlet or slow mix end to its outlet or filtration end. The difference in specific gravity between the water and the particles causes the particles to settle to the bottom of the basin. -

Strategies of Defending Astrology: a Continuing Tradition

Strategies of Defending Astrology: A Continuing Tradition by Teri Gee A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto © Copyright by Teri Gee (2012) Strategies of Defending Astrology: A Continuing Tradition Teri Gee Doctorate of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto 2012 Abstract Astrology is a science which has had an uncertain status throughout its history, from its beginnings in Greco-Roman Antiquity to the medieval Islamic world and Christian Europe which led to frequent debates about its validity and what kind of a place it should have, if any, in various cultures. Written in the second century A.D., Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos is not the earliest surviving text on astrology. However, the complex defense given in the Tetrabiblos will be treated as an important starting point because it changed the way astrology would be justified in Christian and Muslim works and the influence Ptolemy’s presentation had on later works represents a continuation of the method introduced in the Tetrabiblos. Abû Ma‘shar’s Kitâb al- Madkhal al-kabîr ilâ ‘ilm ahk. âm al-nujûm, written in the ninth century, was the most thorough surviving defense from the Islamic world. Roger Bacon’s Opus maius, although not focused solely on advocating astrology, nevertheless, does contain a significant defense which has definite links to the works of both Abû Ma‘shar and Ptolemy. As such, he demonstrates another stage in the development of astrology. -

Colloidal Goldgold

ColloidalColloidal GoldGold Markus Niederberger Email: [email protected] 22.11.2006 OutlineOutline 1) Definition 2) History 3) Synthesis 4) Chemical and Physical Properties 5) Applications 6) References DefinitionDefinition Colloidal gold: Stable suspension of sub-micrometer- sized particles of gold in a liquid ShortShort HistoryHistory ofof GoldGold 4000 B.C.: A culture in Eastern Europe begins to use gold to fashion decorative objects 2500 B.C.: Gold jewelry was found in the Tomb of Djer, king of the First Egyptian Dynasty 1200 B.C.: The Egyptians master the art of beating gold into leaf as well as alloying it with other metals for hardness and color variations 1091 B.C.: Little squares of gold are used in China as a form of money 300 B.C.: Greeks and Jews of ancient Alexandria start to practice Alchemy, the quest of turning base metals into gold 200 B.C.: The Romans gain access to the gold mining region of Spain 50 B.C.: The Romans begin issuing a gold coin called the Aureus 1284 A.D.: Venice introduces the gold Ducat, which soon becomes the most popular coin in the world Source: National Mining Association, Washington HistoryHistory ofof GoldGold ColloidsColloids andand theirtheir ApplicationApplication History: Gold in Medicine Humankind has linked the lustre of gold with the warm, life-giving light of the sun. In cultures, which deified the sun, gold represented its earthly form. The earliest records of the use of gold for medicinal and healing purposes come from Alexandria, Egypt. Over 5000 years ago the Egyptians ingested gold for mental and bodily purification. -

The Philosopher's Stone

The Philosopher’s Stone Dennis William Hauck, Ph.D., FRC Dennis William Hauck is the Project Curator of the new Alchemy Museum, to be built at Rosicrucian Park in San Jose, California. He is an author and alchemist working to facilitate personal and planetary transformation through the application of the ancient principles of alchemy. Frater Hauck has translated a number of important alchemy manuscripts dating back to the fourteenth century and has published dozens of books on the subject. He is the founder of the International Alchemy Conference (AlchemyConference.com), an instructor in alchemy (AlchemyStudy.com), and is president of the International Alchemy Guild (AlchemyGuild. org). His websites are AlchemyLab.com and DWHauck.com. Frater Hauck was a presenter at the “Hidden in Plain Sight” esoteric conference held at Rosicrucian Park. His paper based on that presentation entitled “Materia Prima: The Nature of the First Matter in the Esoteric and Scientific Traditions” can be found in Volume 8 of the Rose+Croix Journal - http://rosecroixjournal.org/issues/2011/articles/vol8_72_88_hauck.pdf. he Philosopher’s Stone was the base metal into incorruptible gold, it could key to success in alchemy and similarly transform humans from mortal Thad many uses. Not only could (corruptible) beings into immortal (incor- it instantly transmute any metal into ruptible) beings. gold, but it was the alkahest or universal However, it is important to remember solvent, which dissolved every substance that the Stone was not just a philosophical immersed in it and immediately extracted possibility or symbol to alchemists. Both its Quintessence or active essence. The Eastern and Western alchemists believed it Stone was also used in the preparation was a tangible physical object they could of the Grand Elixir and aurum potabile create in their laboratories. -

Ethan Allen Hitchcock Soldier—Humanitarian—Scholar Discoverer of the "True Subject'' of the Hermetic Art

Ethan Allen Hitchcock Soldier—Humanitarian—Scholar Discoverer of the "True Subject'' of the Hermetic Art BY I. BERNARD COHEN TN seeking for a subject for this paper, it had seemed to me J- that it might prove valuable to discuss certain aspects of our American culture from the vantage point of my own speciality as historian of science and to illustrate for you the way in which the study of the history of science may provide new emphases in American cultural history—sometimes considerably at variance with established interpretations. American cultural history has, thus far, been written largely with the history of science left out. I shall not go into the reasons for that omission—they are fairly obvious in the light of the youth of the history of science as a serious, independent discipline. This subject enables us to form new ideas about the state of our culture at various periods, it casts light on the effects of American creativity upon Europeans, and it focuses attention on neglected figures whose value is appreciated abroad but not at home. For example, our opinion of American higher education in the early nineteenth century is altered when we discover that at Harvard and elsewhere the amount of required science and mathematics was exactly three times as great as it is today in an "age of science."^ In the eighteenth century when, according to Barrett Wendell, Harvard gave its » See "Harvard and the Scientific Spirit," Harvard Alumni Bull, 7 Feb. 1948. 3O AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY [April, students only "a fair training in Latin -

Tensions Between Scientia and Ars in Medieval Natural Philosophy and Magic Isabelle Draelants

The notion of ‘Properties’ : Tensions between Scientia and Ars in medieval natural philosophy and magic Isabelle Draelants To cite this version: Isabelle Draelants. The notion of ‘Properties’ : Tensions between Scientia and Ars in medieval natural philosophy and magic. Sophie PAGE – Catherine RIDER, eds., The Routledge History of Medieval Magic, p. 169-186, 2019. halshs-03092184 HAL Id: halshs-03092184 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03092184 Submitted on 16 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. This article was downloaded by: University College London On: 27 Nov 2019 Access details: subscription number 11237 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge History of Medieval Magic Sophie Page, Catherine Rider The notion of properties Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613192-14 Isabelle Draelants Published online on: 20 Feb 2019 How to cite :- Isabelle Draelants. 20 Feb 2019, The notion of properties from: The Routledge History of Medieval Magic Routledge Accessed on: 27 Nov 2019 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613192-14 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. -

A Lexicon of Alchemy

A Lexicon of Alchemy by Martin Rulandus the Elder Translated by Arthur E. Waite John M. Watkins London 1893 / 1964 (250 Copies) A Lexicon of Alchemy or Alchemical Dictionary Containing a full and plain explanation of all obscure words, Hermetic subjects, and arcane phrases of Paracelsus. by Martin Rulandus Philosopher, Doctor, and Private Physician to the August Person of the Emperor. [With the Privilege of His majesty the Emperor for the space of ten years] By the care and expense of Zachariah Palthenus, Bookseller, in the Free Republic of Frankfurt. 1612 PREFACE To the Most Reverend and Most Serene Prince and Lord, The Lord Henry JULIUS, Bishop of Halberstadt, Duke of Brunswick, and Burgrave of Luna; His Lordship’s mos devout and humble servant wishes Health and Peace. In the deep considerations of the Hermetic and Paracelsian writings, that has well-nigh come to pass which of old overtook the Sons of Shem at the building of the Tower of Babel. For these, carried away by vainglory, with audacious foolhardiness to rear up a vast pile into heaven, so to secure unto themselves an immortal name, but, disordered by a confusion and multiplicity of barbarous tongues, were ingloriously forced. In like manner, the searchers of Hermetic works, deterred by the obscurity of the terms which are met with in so many places, and by the difficulty of interpreting the hieroglyphs, hold the most noble art in contempt; while others, desiring to penetrate by main force into the mysteries of the terms and subjects, endeavour to tear away the concealed truth from the folds of its coverings, but bestow all their trouble in vain, and have only the reward of the children of Shem for their incredible pain and labour. -

Alchemy Rediscovered and Restored

ALCHEMY REDISCOVERED AND RESTORED BY ARCHIBALD COCKREN WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE EXTRACTION OF THE SEED OF METALS AND THE PREPARATION OF THE MEDICINAL ELIXIR ACCORDING TO THE PRACTICE OF THE HERMETIC ART AND OF THE ALKAHEST OF THE PHILOSOPHER TO MRS. MEYER SASSOON PHILADELPHIA, DAVID MCKAY ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN 1941 Alchemy Rediscovered And Restored By Archibald Cockren. This web edition created and published by Global Grey 2013. GLOBAL GREY NOTHING BUT E-BOOKS TABLE OF CONTENTS THE SMARAGDINE TABLES OF HERMES TRISMEGISTUS FOREWORD PART I. HISTORICAL CHAPTER I. BEGINNINGS OF ALCHEMY CHAPTER II. EARLY EUROPEAN ALCHEMISTS CHAPTER III. THE STORY OF NICHOLAS FLAMEL CHAPTER IV. BASIL VALENTINE CHAPTER V. PARACELSUS CHAPTER VI. ALCHEMY IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES CHAPTER VII. ENGLISH ALCHEMISTS CHAPTER VIII. THE COMTE DE ST. GERMAIN PART II. THEORETICAL CHAPTER I. THE SEED OF METALS CHAPTER II. THE SPIRIT OF MERCURY CHAPTER III. THE QUINTESSENCE (I) THE QUINTESSENCE. (II) CHAPTER IV. THE QUINTESSENCE IN DAILY LIFE PART III CHAPTER I. THE MEDICINE FROM METALS CHAPTER II. PRACTICAL CONCLUSION 'AUREUS,' OR THE GOLDEN TRACTATE SECTION I SECTION II SECTION III SECTION IV SECTION V SECTION VI SECTION VII THE BOOK OF THE REVELATION OF HERMES 1 Alchemy Rediscovered And Restored By Archibald Cockren THE SMARAGDINE TABLES OF HERMES TRISMEGISTUS said to be found in the Valley of Ebron, after the Flood. 1. I speak not fiction, but what is certain and most true. 2. What is below is like that which is above, and what is above is like that which is below for performing the miracle of one thing.