Copyright by Annalyda Álvarez-Calderón 2009 Stony Brook University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quispe Pacco Sandro.Pdf

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN SECUNDARIA COMPLEJO ARQUEOLÓGICO DE MAUKA LLACTA DEL DISTRITO DE NUÑOA TESIS PRESENTADA POR: SANDRO QUISPE PACCO PARA OPTAR EL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADO EN EDUCACIÓN CON MENCIÓN EN LA ESPECIALIDAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES PROMOCIÓN 2016- II PUNO- PERÚ 2017 1 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN SEUNDARIA COMPLEJO ARQUEOLÓGICO DE MAUKA LLACTA DEL D ���.r NUÑOA SANDRO QUISPE PACCO APROBADA POR EL SIGUIENTE JURADO: PRESIDENTE e;- • -- PRIMER MIEMBRO --------------------- > '" ... _:J&ª··--·--••__--s;; E • Dr. Jorge Alfredo Ortiz Del Carpio SEGUNDO MIEMBRO --------M--.-S--c--. --R--e-b-�eca Alano�ca G�u�tiérre-z-- -----�--- f DIRECTOR ASESOR ------------------ , M.Sc. Lor-- �VÍlmore Lovón -L-o--v-ó--n-- ------------- Área: Disciplinas Científicas Tema: Patrimonio Histórico Cultural DEDICATORIA Dedico este informe de investigación a Dios, a mi madre por su apoyo incondicional, durante estos años de estudio en el nivel pregrado en la UNA - Puno. Para todos con los que comparto el día a día, a ellos hago la dedicatoria. 2 AGRADECIMIENTO Mi principal agradecimiento a la Universidad Nacional del Altiplano – Puno primera casa superior de estudios de la región de Puno. A la Facultad de Educación, en especial a los docentes de la especialidad de Ciencias Sociales, que han sido parte de nuestro crecimiento personal y profesional. A mi familia por haberme apoyado económica y moralmente en -

Urban Interrelation and Regional Patterning in the Department of Puno, Southern Peru Jean Morisset

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 04:15 Cahiers de géographie du Québec Urban interrelation and regional patterning in the department of Puno, Southern Peru Jean Morisset Volume 20, numéro 49, 1976 Résumé de l'article Le département de Puno s'inscrit autour du lac Titicaca (3 800 m au-dessus du URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/021311ar niveau de la mer) pour occuper un vaste plateau (l'altiplano) ainsi que les DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/021311ar hautes chaînes andines (la puna) et; déborder au nord vers le bassin amazonien (la selva). Aller au sommaire du numéro En utilisant à la fois des informations recueillies lors d'enquêtes sur le terrain et des données de recensement (1940 et 1961), cet essai poursuit un double objectif: on a tenté d'analyser d'une part, l'évolution et l'interdépendance des Éditeur(s) principaux centres du département de Puno pour proposer, d'autre part, une régionalisation à partir des structures géo-spatiales et des organisations Département de géographie de l'Université Laval administratives. De plus, on a brièvement traité de la nature des agglomérations et on a réalisé une analyse quantitative ISSN regroupant 30 variables reportées sur les 85 districts du département. 0007-9766 (imprimé) L'auteur conclut en suggérant que toute planification est un processus qui doit 1708-8968 (numérique) aboutir à un compromis entre des composantes spatio-économiques (planificaciôn tecno-crética) et des composantes socio-culturelles (planificaciôn Découvrir la revue de base). Citer cet article Morisset, J. (1976). Urban interrelation and regional patterning in the department of Puno, Southern Peru. -

Guillermo Enrique Billinghurst Angulo

GUILLERMO ENRIQUE BILLINGHURST ANGULO Guillermo Billinghurst nació en Arica el 27 de julio de 1851. Era hijo de Guillermo Eugenio Billinghurst Agrelo, natural de Buenos Aires; y Belisaria Angulo Tudela, (Arica, 1830 – 20/2/1866)1. Sus abuelos paternos eran el británico William Robert Billinghurst y la argentina Francisca Agrelo Moreyra. El matrimonio Billinghurst Agrelo tuvo por hijos a Daniel Mariano, Guillermo Eugenio, Roberta Luisa, Catalina Florencia y Roberto Gay. A William Billinghurst el gobierno de las Provincias Unidas del Río de La Plata le otorgó la ciudadanía argentina por sus servicios a la independencia. Guillermo Enrique Billinghurst fue bautizado el 13 de octubre de 1851 en su ciudad natal, teniendo como padrinos a Ruperto Fernández y Paula Tudela. Realizó sus primeros estudios en Arica, continuándolos en el Colegio inglés de Goldfinch y Blühm en Valparaíso. Allí conoció a Alfonso Ugarte, el futuro héroe, con quien traba una sólida amistad. Se trasladó a Buenos Aires para seguir ingeniería. El 13 de agosto de 1868 se produjo un terremoto, que tuvo por epicentro el Océano Pacífico –frente a Tacna– y que asoló el sur de nuestro país, especialmente las ciudades de Arequipa, Moquegua, Tacna, Islay, Arica e Iquique. Luego del sismo un Tsunami arrasó las costas peruanas desde Pisco hasta Iquique. Entre las víctimas de la naturaleza estuvo su padre, quien murió ahogado, lo que motivó el retorno de Guillermo Billinghurst a nuestro país, para asumir la conducción de los negocios salitreros de su familia. El 15 de abril de 1879 contrajo nupcias con María Emilia Rodríguez Prieto Cañipa (Arica, 10/5/1860 - ¿?). -

El Verdadero Poder De Los Alcaldes

El verdadero poder * Texto elaborado por la redacción de Quehacer con el apoyo del historiador Eduardo Toche y del sociólogo Mario Zolezzi. Fotos: Manuel Méndez 10 de los alcaldes* 11 PODER Y SOCIEDAD n el Perú existe la idea de que las alcaldías representan un escalón Enecesario para llegar a cargos más importantes, como la Presi- dencia de la República. Sin embargo, la historia refuta esta visión ya que, con la excepción de Guillermo Billinghurst, ningún otro alcalde ha llegado a ser presidente. El político del pan grande, sin duda populista, fue derrocado por el mariscal Óscar R. Benavides. Lima siempre ha sido una ciudad conservadora, tanto en sus cos- tumbres como en sus opciones políticas. Durante el gobierno revolucio- nario de Juan Velasco Alvarado, de tinte reformista, la designación “a dedo” de los alcaldes tuvo un perfil más bien empresarial, desvinculado políticamente de las organizaciones populares. Y eso que al gobierno militar le faltaba a gritos contacto con el mundo popular. SINAMOS, una creación estrictamente política del velasquismo, habría podido de lo más bien proponer alcaldes con llegada al universo barrial. Desde su fundación española, Lima ha tenido más de trescientos alcaldes, muchos de ellos nombrados por el gobierno central. El pri- mero fue Nicolás de Ribera, el Viejo, en 1535, y desde esa fecha hasta 1839 se sucedieron más de 170 gestiones municipales. La Constitución de 1839 no consideró la instancia municipal. Recién en 1857 renace la Municipalidad de Lima y fue gobernada por un solo alcalde. El último en tentar el sillón presidencial fue Luis Castañeda Lossio y su participación en la campaña del año 2011 fue bastante pobre, demostrando que una cosa es con guitarra y otra con cajón. -

New Age Tourism and Evangelicalism in the 'Last

NEGOTIATING EVANGELICALISM AND NEW AGE TOURISM THROUGH QUECHUA ONTOLOGIES IN CUZCO, PERU by Guillermo Salas Carreño A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Bruce Mannheim, Chair Professor Judith T. Irvine Professor Paul C. Johnson Professor Webb Keane Professor Marisol de la Cadena, University of California Davis © Guillermo Salas Carreño All rights reserved 2012 To Stéphanie ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was able to arrive to its final shape thanks to the support of many throughout its development. First of all I would like to thank the people of the community of Hapu (Paucartambo, Cuzco) who allowed me to stay at their community, participate in their daily life and in their festivities. Many thanks also to those who showed notable patience as well as engagement with a visitor who asked strange and absurd questions in a far from perfect Quechua. Because of the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board’s regulations I find myself unable to fully disclose their names. Given their public position of authority that allows me to mention them directly, I deeply thank the directive board of the community through its then president Francisco Apasa and the vice president José Machacca. Beyond the authorities, I particularly want to thank my compadres don Luis and doña Martina, Fabian and Viviana, José and María, Tomas and Florencia, and Francisco and Epifania for the many hours spent in their homes and their fields, sharing their food and daily tasks, and for their kindness in guiding me in Hapu, allowing me to participate in their daily life and answering my many questions. -

Rural Credit in Ten Rural Communities in Three Districts of the Region of Puno

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No.14 (2021), 298- 312 Research Article RURAL CREDIT IN TEN RURAL COMMUNITIES IN THREE DISTRICTS OF THE REGION OF PUNO Ada Luz Flores, O.1; Luis A. Palao2, Marco Vera Z3., Ernesto Chura Y.4. 1 Escuela Posgrado Universidad Nacional del Altiplano Puno Perú, [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0565-9720 2 Universidad Nacional del Altiplano, Puno Perú [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8527-8866 3 Universidad Nacional del Altiplano Puno Perú [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2014-2845 4 Universidad Nacional del Altiplano, Puno Perú, [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4227-220X Abstract The Puno region has two different zones in the native language, the northern zone is Quechua and the southern zone is Aymara. This research was carried out in the southern zone, in three districts and ten rural communities organized in an Association of Agricultural Producers and Fishermen of the Lake (APAPEL), where two credit institutions, CEDER and EDYFICAR through CARE PERU, have promoted rural credit in order to contribute to the improvement of the income of rural families. The objectives of the research are: a) identify the orientation of rural credit according to the type of activity, b) analyze the effect of rural credit on family income, and c) determine the delinquency rate of rural credit granted by two credit institutions. The method used is descriptive of evaluative type of inductive-deductive nature, under the microeconomic approach taking into account the CAUSE-EFFECT relationship. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

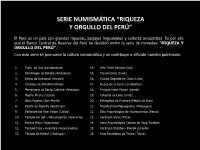

SERIE NUMISMÁTICA “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ” El Perú es un país con grandes riquezas, paisajes inigualables y culturas ancestrales. Es por ello que el Banco Central de Reserva del Perú ha decidido emitir la serie de monedas: “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ”. Con esta serie se promueve la cultura numismática y se contribuye a difundir nuestro patrimonio. 1. Tumi de Oro (Lambayeque) 14. Arte Textil Paracas (Ica) 2. Sarcófagos de Karajía (Amazonas) 15. Tunanmarca (Junín) 3. Estela de Raimondi (Ancash) 16. Ciudad Sagrada de Caral (Lima) 4. Chullpas de Sillustani (Puno) 17. Huaca de la Luna (La Libertad) 5. Monasterio de Santa Catalina (Arequipa) 18. Antiguo Hotel Palace (Loreto) 6. Machu Picchu (Cusco) 19. Catedral de Lima (Lima) 7. Gran Pajatén (San Martín) 20. Petroglifos de Pusharo (Madre de Dios) 8. Piedra de Saywite (Apurimac) 21. Arquitectura Moqueguana (Moquegua) 9. Fortaleza del Real Felipe (Callao) 22. Sitio Arqueológico de Huarautambo (Pasco) 10. Templo del Sol – Vilcashuamán (Ayacucho) 23. Cerámica Vicús (Piura) 11. Kuntur Wasi (Cajamarca) 24. Zona Arqueológica Cabeza de Vaca Tumbes) 12. Templo Inca - Huaytará (Huancavelica) 25. Cerámica Shipibo – Konibo (Ucayali) 13. Templo de Kotosh (Huánuco) 26. Arco Parabólico de Tacna (Tacna) 1 TUMI DE ORO Especificaciones Técnicas En el reverso se aprecia en el centro el Tumi de Oro, instrumento de hoja corta, semilunar y empuñadura escultórica con la figura de ÑAYLAMP ícono mitológico de la Cultura Lambayeque. Al lado izquierdo del Tumi, la marca de la Casa Nacional de Moneda sobre un diseño geométrico de líneas verticales. Al lado derecho del Tumi, la denominación en números, el nombre de la unidad monetaria sobre unas líneas ondulantes, debajo la frase TUMI DE ORO, S. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A History of Guelaguetza in Zapotec Communities of the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, 16th Century to the Present Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7tv1p1rr Author Flores-Marcial, Xochitl Marina Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles A History of Guelaguetza in Zapotec Communities of the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, 16th Century to the Present A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Xóchitl Marina Flores-Marcial 2015 © Copyright by Xóchitl Marina Flores-Marcial 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION A History of Guelaguetza in Zapotec Communities of the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, 16th Century to the Present by Xóchitl Marina Flores-Marcial Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Kevin B. Terraciano, Chair My project traces the evolution of the Zapotec cultural practice of guelaguetza, an indigenous sharing system of collaboration and exchange in Mexico, from pre-Columbian and colonial times to the present. Ironically, the term "guelaguetza" was appropriated by the Mexican government in the twentieth century to promote an annual dance festival in the city of Oaxaca that has little to do with the actual meaning of the indigenous tradition. My analysis of Zapotec-language alphabetic sources from the Central Valley of Oaxaca, written from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, reveals that Zapotecs actively participated in the sharing system during this long period of transformation. My project demonstrates that the Zapotec sharing economy functioned to build and reinforce social networks among households in Zapotec communities. -

Esta Propuesta Legislativa Busca Llenar Un Vacío Legal... El Señor PRESIDENTE (Luis Gonzales Po- Sada Eyzaguirre).— Disculpe

1064 Diario de los Debates - PRIMERA LEGISLATURA ORDINARIA DE 2007 - TOMO II Esta propuesta legislativa busca llenar un vacío Se deja constancia del voto a favor de los congre- legal... sistas Rebaza Martell, Peralta Cruz, Beteta Ru- bín, Maslucán Culqui y Otárola Peñaranda. El señor PRESIDENTE (Luis Gonzales Po- sada Eyzaguirre).— Disculpe, congresista. “Votación para exonerar de segunda votación el texto sustitutorio del Le estábamos dando el uso de la palabra para Proyecto N.° 911 que pudiera solicitar que se exonere de segunda votación el proyecto de ley que acabamos de apro- Señores congresistas que votaron a favor: bar de manera abrumadora. Abugattás Majluf, Alegría Pastor, Anaya Oropeza, Andrade Carmona, Balta Salazar, Bruce Montes La señora CHACÓN DE VETTO- de Oca, Cajahuanca Rosales, Calderón Castro, RI (GPF).— Señor Presidente, no Carpio Guerrero, Carrasco Távara, Cenzano he solicitado exoneración de segun- Sierralta, Eguren Neuenschwander, Espinoza da votación. Ramos, Estrada Choque, Falla Lamadrid, Flores Torres, Galindo Sandoval, Guevara Trelles, Seguiremos el Reglamento, señor Herrera Pumayauli, Huancahuari Páucar, Huerta Presidente. Díaz, Lazo Ríos de Hornung, León Minaya, León Zapata, Luizar Obregón, Macedo Sánchez, El señor PRESIDENTE (Luis Gonzales Po- Mayorga Miranda, Mendoza del Solar, Nájar sada Eyzaguirre).— Correcto. Kokally, Negreiros Criado, Núñez Román, Peña Angulo, Pérez del Solar Cuculiza, Perry Cruz, Puede hacer uso de la palabra el congresista Ramos Prudencio, Reymundo Mercado, Robles Oswaldo Luizar. López, Rodríguez Zavaleta, Ruiz Delgado, Ruiz Silva, Salazar Leguía, Saldaña Tovar, Sánchez El señor LUIZAR OBREGÓN Ortiz, Sasieta Morales, Serna Guzmán, Silva Díaz, (N-UPP).— Presidente, entiendo Sucari Cari, Sumire de Conde, Supa Huamán, que la posición de la congresista Torres Caro, Urquizo Maggia, Urtecho Medina, Cecilia Chacón es la posición de su Valle Riestra González Olaechea, Vargas Fernán- bancada. -

Bio-Filtration of Helminth Eggs and Coliforms from Municipal Sewage for Agricultural Reuse in Peru

Bio-filtration of helminth eggs and coliforms from municipal sewage for agricultural reuse in Peru Rosa Elena Yaya Beas Thesis committee Promotors Prof. Dr G. Zeeman Personal chair at the Sub-department of Environmental Technology Wageningen University Prof. Dr J.B. van Lier Professor of Anaerobic Wastewater Treatment for Reuse and Irrigation Delft University of Technology Co-promotor Dr K. Kujawa-Roeleveld Lecturer at the Sub-department of Environmental Technology Wageningen University Other members Dr N. Hofstra, Wageningen University Prof. Dr M.H. Zwietering, Wageningen University Prof. Dr C.A. de Lemos Chernicharo, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil Dr M. Ronteltap, UNESCO-IHE, Delft This research was conducted under the auspices of the Graduate School of SENSE (Socio-Economic and Natural Sciences of the Environment). II Bio-filtration of helminth eggs and coliforms from municipal sewage for agricultural reuse in Peru Rosa Elena Yaya Beas Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr A.P.J. Mol, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Wednesday 20 January 2016 at 1.30 p.m. in the Aula. III Rosa Elena Yaya Beas Bio-filtration of helminth eggs and coliforms from municipal sewage for agricultural reuse in Peru 198 pages. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2016) With references, with summaries in English and Dutch ISBN 978-94-6173-494-5 IV V Abstract Where fresh water resources are scarce, treated wastewater becomes an attractive alternative for agricultural irrigation. -

CBD First National Report

BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN PERU __________________________________________________________ LIMA-PERU NATIONAL REPORT December 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................ 6 1 PROPOSED PROGRESS REPORT MATRIX............................................... 20 I INTRODUCTION......................................................................................... 29 II BACKGROUND.......................................................................................... 31 a Status and trends of knowledge, conservation and use of biodiversity. ..................................................................................................... 31 b. Direct (proximal) and indirect (ultimate) threats to biodiversity and its management ......................................................................................... 36 c. The value of diversity in terms of conservation and sustainable use.................................................................................................................... 47 d. Legal & political framework for the conservation and use of biodiversity ...................................................................................................... 51 e. Institutional responsibilities and capacities................................................. 58 III NATIONAL GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ON THE CONSERVATION AND SUSTAINABLE USE OF BIODIVERSITY.............................................................................................. 77 -

Wildpotato Collecting Expedition in Southern Peru

A Arner J of Potato Res (1999) 76:103-119 103 Wild Potato Collecting Expedition in Southern Peru (Departments of Apurimac, Arequipa, Cusco, Moquegua Puno, Tacna) in 1998: Taxonomy and New Genetic Resources David M. Spooner*\ Alberto Salas L6pez2,Z6simo Huaman2, and Robert J. Hijmans2 'United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Department of Horticulture, University of Wisconsin, 1575 Linden Drive, Madison, WI, 53706-1590. Tel: 608-262-0159; FAX: 608-262-4743; email: [email protected]) 'International Potato Center (CIP), Apartado 1558, La Molina, Lima 12, Peru. ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Peruhas 103 taxa of wild potatoes (species, sub- Wild and cultivated tuber-bearing potatoes (Solanum species, varieties, and forms) according to Hawkes sect. Petota) are distributed from the southwestern United (1990; modified by us by a reduction of species in the States to south-central Chile. The latest comprehensive tax- Solanum brevicaule complex) and including taxa onomic treatment of potatoes (Hawkes, 1990) recogllized 216 described by C. Ochoa since 1989. Sixty-nine of these tuber-bearing species, with 101 taxa (here to include species, 103 taxa (67%) were unavailable from any ofthe world's subspecies, varieties and forms) from Peru. Ochoa (1989, genebanks and 85 of them (83%) had less than three 1992b, 1994a,b) described ten additional Peruvian taxa rais- germplasm accessions. We conducted a collaborative ing the total to 111. We lower this number to 103 with a mod- Peru(INIA), United States (NRSP-6), and International ification of species in the Solanum brevicaule complex. Potato Center (CIP) wild potato (Solanum sect. Petota) Sixty-nine of these 103 species (67%) were unavailable from collecting expedition in Peru to collect germplasm and any ofthe world's genebanks and 85 of them (83%) had less gather taxonomic data.