European Urban and Regional Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D.1.1 SWOT REPORT SWOT Analysis and Status

Ref. Ares(2019)1367647 - 28/02/2019 D.1.1 SWOT REPORT SWOT Analysis and Status-Quo Description + Participatory Process Documentation WP1 I. Budapest ___________________________ p. 1 II. Bremen ____________________________ p. 64 III. Jerusalem __________________________ p. 156 IV. Malmö _____________________________ p. 191 V. Southend ___________________________ p. 233 VI. Thessaloniki _________________________ p. 284 This deliverable is a product of Work Package 1 in SUNRISE. It assembles in a documentary way the steps taken by the City Partners towards the Co-Identification and Co-Validation of Problems and Needs in their Action Neighbourhoods. The performance and documentation of these steps has been supportet by the Work Package Leader urbanista and the Technical Support Partners Koucky & Partners AB, Rupprecht Consult, TU Vienna and Zaragoza Logistics Center. Page 0 D.1.1 SWOT REPORT | BUDAPEST SWOT Analysis and Status-Quo Description + Participatory Process Documentation City: Budapest ReportinG Period: February 2019 Responsible Author(s): Antal Gertheis, Noémi Szabó (Mobilissimus Ltd.) Responsible Co-Author(s): Urbanista, TU Vienna, Rucpprecht Consult Date: February 28th, 2019 Status: Final Dissemination level: Confidential Page 1 SWOT Analysis and Status-Quo Description | BUDAPEST Find first options for action in your neighbourhood and check the conditions for their implementation! • Collect all relevant data for your neiGhbourhood • Have a closer look at strength, weaknesses, opportunities and threats • Find »Corridors of Options« • Do a »Bottom-up review« • Get a set of thoughtful options for actions that will be developed further in WP2 Page 2 Executive Summary DurinG the process of co-identification in the area of Törökőr, we reached many different groups who were ready to tell their opinion and problems concerning the mobility in the neighbourhood. -

Germany 2020 Human Rights Report

GERMANY 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Germany is a constitutional democracy. Citizens choose their representatives periodically in free and fair multiparty elections. The lower chamber of the federal parliament (Bundestag) elects the chancellor as head of the federal government. The second legislative chamber, the Federal Council (Bundesrat), represents the 16 states at the federal level and is composed of members of the state governments. The country’s 16 states exercise considerable autonomy, including over law enforcement and education. Observers considered the national elections for the Bundestag in 2017 to have been free and fair, as were state elections in 2018, 2019, and 2020. Responsibility for internal and border security is shared by the police forces of the 16 states, the Federal Criminal Police Office, and the federal police. The states’ police forces report to their respective interior ministries; the federal police forces report to the Federal Ministry of the Interior. The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution and the state offices for the protection of the constitution are responsible for gathering intelligence on threats to domestic order and other security functions. The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution reports to the Federal Ministry of the Interior, and the state offices for the same function report to their respective ministries of the interior. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over security forces. Members of the security forces committed few abuses. Significant human rights issues included: crimes involving violence motivated by anti-Semitism and crimes involving violence targeting members of ethnic or religious minority groups motivated by Islamophobia or other forms of right-wing extremism. -

Organisiertes Verbrechen

Organisiertes Verbrechen , au NDEsKRI MI NALAMT WI ES BADE N.. Neben der .Vortragsreihe< gibt das Bundeskriminalamt die Schriftenreihe des Bundeskriminalamtes heraus. Sie enthllt systematische und erschöpfende EinzeldarSlellungen aus dem Gebiet der Kriminologie und Kriminalistik und ist in erster Linie für MiniSlerien, Polizei-, Zoll- u. ä. Behörden, Gerichte, Stuuanwaltschaften und deren Angehörise bestimmL Der Bezug ist nicht über den Buchhandel, sonde,rn nur unmittelbar uber das Bundeskriminalamt - Kl 1 4 - mösrich. Die jährliche GeSl.mtlieferung umfaßt drei Hefte. Als Geschliftsjahr (Lieferungsjahr) ist das Kalenderjahr zugnmde gelegt. Fur das laufende Abonnement ist der Betrag jeweils innerhalb eines Monats nach lieferung des ersten Heftes fällig. Ist bis zum Ablauf dieses Monats keine schriftliche Kündigung erfolgt, verlängert sich das jahresabonnement automatisch um ein weiteres Jahr. Die Rech nu ng wird der ersten Lieferung des jeweiligen jah rgangs beigelegt. Der Preis für das jahresabonnement beträgt 12,- DM. Auch bei Abgabe einzelner Hefte ist der volle Abonnement preis zu bezahlen. Im Interesse einer reibungslosen Verbuchung wird gebeten, bei Einzahlung unbedingt die Im Anschriftenfeld der Rechnung stehende feste Beziehernummer (K ..•) ;anzugeben. Konten der Bundeskasse Frankfurt am Main: P05!Scheckamt Frankfurt am Main Nr. 8971-608 landeszentralbank Frankfurt am Main Nr. 50001020 Zur Vermeidung von Rückfrasen sind bei der Bestellung der .Schriftenreihe. in iedem Falle Beruf oder Dienstgrad sowie die Prlvalilttschrift anzugeben. Verzögerungen bei der Zustellung und unnötige Mehrausgaben sind vermeidbar, wenn Adressenänderungen umgehend dem Bundeskriminalamt - K/1 4 - mitgeteilt werden. Bisher sind folgende noch lieferbare Hefte erschienen: Jah rgang 1960 f1. 4. 1960 bis 31. 12. 1960) Jahrgang 1968 (1. 1.1968 bis 31. 12. 19(8) 5<lchfahndung (MuSlerkatalog) (als Heft 1-3 1. -

Broszura Informacyjna Informationsbroschüre

Informationsbroschüre Broszura informacyjna Verwaltungsgliederung in Deutschland und Polen, Struktur und Arbeit der Sicherheitsbehörden in der Grenzregion Podział administracyjny w Polsce i w Niemczech, struktura i praca organów bezpieczeństwa i porządku publicznego w regionie przygranicznym Förderung der grenzüberschreitenden Zusammenarbeit aus Mitteln des Europäischen Fonds für Regionale Entwicklung (EFRE) im Rahmen des Kooperationsprogramms INTERREG V A Brandenburg–Polen 2014-2020 Dofinansowanie transgranicznej współpracy z Europejskiego Funduszu Rozwoju Regionalnego (EFRR) w ramach Programu Współpracy INTERREG V A Brandenburgia – Polska 2014-2020 Förderung der grenzüberschreitenden Zusammenarbeit aus Mitteln des Europäischen Fonds für Regionale Entwicklung (EFRE) im Rahmen des Kooperationsprogramms INTERREG V A Brandenburg–Polen 2014-2020 Dofinansowanie transgranicznej współpracy z Europejskiego Funduszu Rozwoju Regionalnego (EFRR) w ramach Programu Współpracy INTERREG V A Brandenburgia – Polska 2014-2020 Studienreise zum Deutschen Bundestag, Berlin/Wyjazd Schulung zum Vergleich der administrativen Strukturen in studyjny do niemieckiego Bundestagu, 08.03.2018, Berlin Polen und Deutschland/Szkolenie dotyczące porównania struktur administracyjnych w Polsce i w Niemczech, 06.11.2019, Forst (Lausitz)/Baršć (Łužyca) Impressum Impressum Euroregion Spree-Neiße-Bober Euroregion Sprewa-Nysa-Bóbr Euroregion Spree-Neiße-Bober e.V. Stowarzyszenie Gmin RP Euroregion Berliner Straße 7 “Sprewa - Nysa - Bóbr” 03172 Guben ul. Piastowska 18 Tel.: +49 3561 3133 66-620 Gubin Fax: +49 3561 3171 Tel.:/Fax: +48 68 455 80 50 [email protected] [email protected] www.euroregion-snb.de www.euroregion-snb.pl Euroregion PRO EUROPA VIADRINA Euroregion PRO EUROPA VIADRINA Mittlere Oder e.V. Stowarzyszenie Gmin Polskich Euroregionu Holzmarkt 7 „Pro Europa Viadrina” 15230 Frankfurt (Oder) ul. Władysława Łokietka 22 Tel.: +49 335 66 594 0 66-400 Gorzów Wlkp. -

AUG 2016 Part C.Pdf

Page | 1 CBRNE-TERRORISM NEWSLETTER – August 2016 www.cbrne-terrorism-newsletter.com Page | 2 CBRNE-TERRORISM NEWSLETTER – August 2016 Theresa May tells Islamist extremists: 'The game is up' Source: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/terrorism-in-the-uk/11488942/Theresa-May-tells- Islamist-extremists-The-game-is-up.html March 23 – Theresa May will today tell radical Communities become segregated and cut off Islamists that the "game is up" and that they from one another. Intolerance, hatred and were no longer tolerated in Britain as she bigotry become normalised. Trust is replaced by sets out Tory plans for a crackdown on fear, reciprocity by envy, and solidarity by extremism. division. The Home Secretary is expected to say that a "Where they seek to divide us, our values are future Conservative government target Sharia what unite us. Where they seek to dictate, law, change the rules on granting citizenship to lecture and limit opportunity, our values offer ensure people embrace British values and young people hope and the chance to succeed. introduce "banning orders" for extremist groups. The extremists have no vision for Britain that Radicals will also be barred from working can sustain the dreams and ambitions of its unsupervised with children amid fears that people. Theirs is a negative, depressing and in young people are being brainwashed, while staff fact absurd view of the world - and it is one we at job centres will be required to identify know that in the end we can expose and defeat." vulnerable claimants who may become targets She will appeal to "every single person in for radicalisation. -

Gewalt Gegen/Durch Polizei

Bürgerrechte & Polizei/CILIP 95 (1/2010) Inhalt Gewalt gegen/durch Außerhalb des Polizei Schwerpunkts 3 Polizei und Gewalt 63 Die „fdGO“ als Fetisch: Halbe Wahrheiten, falsche Verfassungsschutz und Ver- Debatte – eine Einleitung fassungsgericht Norbert Pütter Wolf-Dieter Narr 15 Markige Worte – 70 Der Zoll – Mehr als nur eine Von Heiligendamm Verwaltungsbehörde bis zum 1. Mai Otto Diederichs Martin Beck 78 Schweiz: Neues Polizeirecht 21 Wenig Klarheit zum Berufs- für den Bund risiko von PolizistInnen Viktor Györffy Norbert Pütter und und Heiner Busch Randalf Neubert Rubriken 29 Alltägliche Repression gegen Fußballfans Angela Furmaniak 86 Inland aktuell 36 Normalität der Gewalt ge- 90 Meldungen aus Europa gen ImmigrantInnen Dirk Vogelskamp 94 Chronologie 45 Der Verfassungsschutz und 100 Literatur & Aus dem Netz die „linke Gewalt in Berlin Fabian Kunow und 109 Summaries Oliver Schneider 112 MitarbeiterInnen dieser 55 PolizistInnen vor Gericht Ausgabe Tobias Singelnstein Redaktionsmitteilung „Vor vielen Jahren schützte die Uniform den Polizeibeamten, denn sie verlieh Autorität und stellte so klar, wer das Sagen hat, auf der Straße, in jedem Einsatz.“ So steht es auf der Homepage der Gewerkschaft der Polizei, in einem Text, mit dem ihr Bundesvorstand seine „Anti-Gewalt- Kampagne“ vorstellt. Heute müssten PolizeibeamtInnen besonders in Ballungsgebieten an fast jedem Wochenende „ihre Haut zu Markte tragen“. Die GdP, die – vor vielen Jahren – für eine Demokratisierung der Polizei nach innen und außen angetreten ist, wünscht sich nun die Wiederkehr der alten Zeiten: „Der Uniform und allem was dahinter steht … muss zu jeder Zeit Geltung verschafft werden.“ Die Empörung über die angebliche Zunahme von Angriffen auf Poli- zistInnen gehört derzeit zu den Mantras von InnenpolitikerInnen und poli- zeilichen Standesorganisationen. -

They Are Taking Our Women! ?

They are taking our women! ? Analysing the changes in representations of men with an “Oriental” immigrant background as sexual predators in the Bremen newspaper Weser Kurier before and after the New Year’s night in Cologne 2015/2016 International Migration and Ethnic Relations Bachelor Thesis 15 credits Spring 2018 Miriam Schenk 19941230 - 9628 Supervisor: Anne Sofie Roald Word count: 10 053 Abstract Representing “Oriental” men as sexual predators in the media is a recurring theme that has proliferated since the New Year’s night in Cologne in 2015/2016. This study investigates how the representation of men with an immigrant background as sexual predators has developed in the year before and after the New Year’s night in Cologne in 2015/2016 in the Bremen local newspaper Weser Kurier. The aim of the study is to find out in what ways the representation of “Oriental” man has changed, how a moral panic is established, and how an idea of fear is created. To reach this aim Critical Discourse Analysis will be used in combination with theories concerned with “Othering”, moral panic and Orientalism. Because of the limited scope of this study, it should be considered as a base for future research into the field. Key Words: Media representation, Critical Discourse Analysis, sexual harassment, migrants, Germany 2 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Table of Contents 3 1. Introduction 4 2. Aim 4 3. Research Question 4 4. Background 4 4.1. Disposition 4 4.2. Who are the men in question? 5 4.3. New Year’s night in Cologne 2015/2016 5 4.4 Statistics concerning sexual violence in Bremen 6 4.5. -

LANDTAG RHEINLAND-PFALZ Drucksache 17/10708 17

LANDTAG RHEINLAND-PFALZ Drucksache 17/10708 17. Wahlperiode zu Drucksache 17/10167 02. 12. 2019 Antwort des Ministeriums der Finanzen auf die Große Anfrage der Fraktion der CDU – Drucksache 17/10167 – Zulagen für die im Öffentlichen Dienst Beschäftigten und Personalsituation bei Polizei, Berufsfeuerwehr und Justizvollzug in Rheinland-Pfalz Das Ministerium der Finanzen hat die Große Anfrage namens der Landesregierung – Zuleitungsschreiben des Chefs der Staats- kanzlei vom 29. November 2019 – wie folgt beantwortet: I. Allgemeines*) 1. Welche Berufsgruppen (z. B. Polizeibeamtinnen und -beamte, Berufsfeuerwehrbeamtinnen und -beamte und Justizvollzugsbediens- tete) im Öffentlichen Dienst sind in Rheinland-Pfalz zulagenberechtigt? Welche Zulagen gibt es (z. B. Erschwerniszulage, Dienst zu ungünstigen Zeiten-Zulage, Wechselschichtzulage/Zulage für Dienst zu wechselnden Zeiten)? Es wird gebeten, die jeweiligen Zulagen den einzelnen Berufsgruppen zuzuordnen und die jeweilige Höhe der Zulagen mit Stufen aufzulisten. 2. Welche Zulagen gibt es nach Kenntnis der Landesregierung für die unter Ziffer 1 genannten Berufsgruppen in den anderen Bundes- ländern und im Bund? Es wird gebeten, für jedes Bundesland und den Bund die jeweiligen Zulagen den einzelnen Berufsgruppen zuzuordnen und separat aufzuschlüsseln. 3. Wie hoch sind nach Kenntnis der Landesregierung die unter I Ziffer 2 genannten Zulagen? Es wird gebeten, die Angaben für jedes Bundesland und den Bund separat nach Zulagen (mit Stufen) und Berufsgruppe aufzuschlüsseln. Der Tatbestand einer Zulage -

How to Deal with Nazi-Looted Art After Cornelius Gurlitt

PRECLUDING THE STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS? HOW TO DEAL WITH NAZI-LOOTED ART AFTER CORNELIUS GURLITT Phillip Hellwege* The Nazi regime collapsed seventy years ago; still today, we are concerned about the restitution of Nazi-looted art. In recent decades, the public debate in Germany has often focused on restitution by public museums and other public bodies. The recent case of Cornelius Gurlitt has raised the issue of restitution of Nazi-looted art by private individu- als and private entities. German law is clear about this issue: property based claims are time-barred after thirty years. Thus, according to Ger- man law, there is little hope that the original owners will have an en- forceable claim for the restitution of such art. Early in 2014, the Bavarian State Government proposed a legislative reform of the Ger- man Civil Code. The draft bill aims to re-open property based claims for restitution. The draft bill is a direct reaction to the case of Cornelius Gurlitt. This article analyzes the availability of property based claims for the restitution of Nazi-looted art under German law and critically as- sesses the Bavarian State Government's draft bill. My conclusion is not encouraging for the original owners of Nazi-looted art. Even though the Bavarian draft bill breeds hope among Nazi victims and their heirs, who are led to believe that they now have enforceable claims against the present possessors of what was theirs, the truth is that many original owners have forever lost ownership of their art. Re-opening property based claims will not be of any help to these victims, because it is still * Professor of Private Law, Commercial Law, and Legal History, University Augsburg, Germany. -

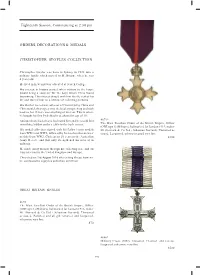

Eighteenth Session, Commencing at 2.30 Pm ORDERS, DECORATIONS

Eighteenth Session, Commencing at 2.30 pm ORDERS, DECORATIONS & MEDALS CHRISTOPHER STOYLES COLLECTION Christopher Stoyles was born in Sydney in 1933 into a military family which moved to Melbourne when he was 4 years old. He lived in Kew and was educated at Scotch College. His interest in history started when visitors to the house would bring a souvenir for the boys which Chris found fascinating. This interest stayed with him for the rest of his life and started him on a lifetime of collecting militaria. His Mother was a keen collector of Crown Derby China and Chris would always peer into the local antique shop and rush back to her if there was anything of interest. This is where he bought his fi rst Pickelhaube at about the age of 10. Antique shops had always fascinated him and he would fi nd 4679* something hidden under a table in the back corner. The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Offi cer (OBE type 1) (Military), hallmarked for London 1919, maker His medal collection started with his Father’s own medals SG (Garrard & Co Ltd - Sebastian Garrard). Unnamed as from WW1 and WW2, followed by his two brother-in-laws' issued. Lacquered, otherwise good very fi ne. medals from WW2. Chris spent 20 years in the Australian $100 Army Reserve and this only strengthened his interest in militaria. He made many friends through his collecting here and on trips overseas to the United Kingdom and Europe. Chris died on 3rd August 2016 after a long illness, however he continued to enjoy his collection until then. -

ENTIDADES POLÍTICAS Y ADMINISTRATIVAS DEL MUNDO Abril De 1999

Servicios Centrales ENTIDADES POLÍTICAS Y ADMINISTRATIVAS DEL MUNDO Abril de 1999 1999/2 ENTIDADES POLÍTICAS Y ADMINISTRATIVAS DEL MUNDO Coordinado por: Marina Arana Montes DIRECTORA DE LA UNIDAD DE PROCESO TÉCNICO Elaborado por: Oscar Muñoz Paz BECARIO-COLABORADOR DE LA BIBLIOTECA (UNIDAD DE PROCESO TÉCNICO) Abril de 1999 Biblioteca Universidad Complutense de Madrid ÍNDICE Página INTRODUCCIÓN.......................................................................................................... 1 AFRICA ......................................................................................................................... 7 AMÉRICA.................................................................................................................... 19 ASIA............................................................................................................................. 63 EUROPA ...................................................................................................................... 81 OCEANÍA .................................................................................................................. 203 ORGANIZACIONES MULTINACIONALES.......................................................... 211 DIRECCIONES WEB DE INTERÉS ........................................................................ 217 INTRODUCCIÓN Las instituciones político-administrativas presentan bastantes dificultades a la hora de crear registros catalográficos con puntos de acceso normalizados. Deben ir en su idioma original y, en ciertos -

Annual Report 2015

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Period under review: 1 January – 31 December 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 of the Federal Agency and of the Joint Commission Period under review: 1 January – 31 December 2015 © 2016 National Agency for the Prevention of Torture All rights reserved Printed by Heimsheim Prison National Agency for the Prevention of Torture Viktoriastraße 35 D-65189 Wiesbaden Tel.: +49 (0)611-160 222 8-18 Fax: +49 (0)611-160 222 8-29 Email: [email protected] www.nationale-stelle.de An electronic version of this Annual Report can be retrieved from the “Publications” section at: www.nationale-stelle.de. TABLE OF CONTENTS I General information about the work of the National Agency....................................................................................11 1 – Background.................................................................................................................................................................12 1.1 – Institutional framework ..........................................................................................................................................12 1.2 – Tasks ........................................................................................................................................................................12 1.3 – Powers......................................................................................................................................................................12 2 – The National Agency in the international context...................................................................................................13