Article Title: Some Reflections on Plains Caddoan Origins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roger T1." Grange, Jr. a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The

Ceramic relationships in the Central Plains Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Grange, Roger Tibbets, 1927- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 18:53:20 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565603 CERAMIC RELATIONSHIPS' IN THE CENTRAL PLAINS ^ > 0 ^ . Roger T1." Grange, Jr. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Roger T, Grange, Jr»________________________ entitled ______Ceramic Relationships in the Central_____ _____Plains_______________________________________ be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of _____Doctor of Philosophy________________________ April 26. 1962 Dissertation Director Date After inspection of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:* 5 / ? / ^ t 5 /? / C 2-— A / , - r y /n / *This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination. The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in The University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. -

Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany

Kindscher, L. Yellow Bird, M. Yellow Bird & Sutton Yellow M. Bird, Yellow L. Kindscher, Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany This book describes the traditional use of wild plants among the Arikara (Sahnish) for food, medicine, craft, and other uses. The Arikara grew corn, hunted and foraged, and traded with other tribes in the northern Great Plains. Their villages were located along the Sahnish (Arikara) Missouri River in northern South Dakota and North Dakota. Today, many of them live at Fort Berthold Reservation, North Dakota, as part of the MHA (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara) Ethnobotany Nation. We document the use of 106 species from 31 plant families, based primarily on the work of Melvin Gilmore, who recorded Arikara ethnobotany from 1916 to 1935. Gilmore interviewed elders for their stories and accounts of traditional plant use, collected material goods, and wrote a draft manuscript, but was not able to complete it due to debilitating illness. Fortunately, his field notes, manuscripts, and papers were archived and form the core of the present volume. Gilmore’s detailed description is augmented here with historical accounts of the Arikara gleaned from the journals of Great Plains explorers—Lewis and Clark, John Bradbury, Pierre Tabeau, and others. Additional plant uses and nomenclature is based on the field notes of linguist Douglas R. Parks, who carried out detailed documentation of the Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany tribe’s language from 1970–2001. Although based on these historical sources, the present volume features updated modern botanical nomenclature, contemporary spelling and interpretation of Arikara plant names, and color photographs and range maps of each species. -

Federal Register/Vol. 73, No. 45/Thursday, March 6, 2008/Notices

12212 Federal Register / Vol. 73, No. 45 / Thursday, March 6, 2008 / Notices known individual was identified. No Nebraska State Historical Society and Box 1286, Hastings, NE 68902, associated funerary objects are present. museum records are consistent with telephone (402) 461–2399, before April Research conducted at the Nebraska information on the site known as the 7, 2008. Repatriation of the human State Historical Society identifies at Hanna Larson Site. The site was remains and associated funerary objects least 15 sites in the area around Palmer. occupied form A.D. 1650 to A.D. 1750 to the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma may One site is known as the Palmer Village and is culturally identified with the proceed after that date if no additional (25HW1), which is a well known site Lower Loup Focus of the Pahuk Aspect claimants come forward. that was occupied by the Skidi band of of the late Ceramic Period. The Hastings Museum is responsible the Pawnee from at least A.D. 1804 to The Lower Loup Phase sites are for notifying the Crow Tribe of Montana; A.D. 1836, and was observed and located in areas also associated with Omaha Tribe of Nebraska; Otoe– recorded by a number of explorers to the historic Pawnee sites. The Lower Loup Missouria Tribe of Indians, Oklahoma; area. Museum officials have been able to material culture suggests that they are Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma; Ponca document Mr. Brooking and Mr. Hill as ancestors of the Pawnee. Descendants of Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma; Ponca having conducted excavations at the the Pawnee are members of the Pawnee Tribe of Nebraska; Sac & Fox Nation of Palmer Village. -

Police and Punishment Among Native Americans of the Plains William Christie Macleod

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 28 Article 3 Issue 2 July-August Summer 1937 Police and Punishment Among Native Americans of the Plains William Christie MacLeod Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation William Christie MacLeod, Police and Punishment Among Native Americans of the Plains, 28 Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 181 (1937-1938) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. POLICE AND PUNISHMENT AMONG NATIVE AMERICANS OF THE PLAINS WMLwA CIMISTIE MACLEOD* The American Indians of the Plains and the adjacent wood- lands have been given much credit in the literature concerning them, with regard to their abilities as warriors. Neither scientific nor popular writings, however, have taken much note of matters concerning their internal polity. The "tribe" is something we con- ceive of rather chaotically. Yet these native peoples were as neatly and elaborately organized politically as many civilized peoples- and-which is what interests in this paper-as an aspect of their political organizations there was included an important and effective police system, clothed with powers to enforce its orders, and able to inflict severe punishment for disobedience. Neglected as this phase of the life of these peoples has been, nevertheless there is available in the literature sufficient data to enable us to present a fairly complete, though imperfect, picture of these police organizations.1 Among these native American peoples there was no military force or "army" standing above or apart from the armed body of the people. -

Pipestone National Monument, Minnesota Native American Cultural Affiliation and Traditional Association Study

Pipestone National Monument, Minnesota Native American Cultural Affiliation and Traditional Association Study Item Type Report Authors Zedeño, M. Nieves; Basaldu, R.C. Publisher Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona Download date 24/09/2021 17:33:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/292671 PIPESTONE NATIONAL MONUMENT, MINNESOTA NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURAL AFFILIATION AND TRADITIONAL ASSOCIATION STUDY Final Report June 30, 2004 María Nieves Zedeño Robert Christopher Basaldú Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA Tucson, AZ 85721 PIPESTONE NATIONAL MONUMENT, MINNESOTA NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURAL AFFILIATION AND TRADITIONAL ASSOCIA- TION STUDY Final Report Prepared by María Nieves Zedeño And Robert Christopher Basaldú Prepared for National Park Service Midwest Region Under Task Agreement 27 of Cooperative Agreement H8601010007 R.W. Stoffle and M. N. Zedeño, Principal Investigators Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 86721 June 30, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................................................iii SUMMARY OF FINDINGS ......................................................................................................... iv CHAPTER ONE – STUDY OVERVIEW...................................................................................... 1 Geographic and Cultural Focus of the Research............................................................................ -

Ioway-Otoe-Missouria ~ English A

100 Ioway-Otoe-Missouria ~ English [JGT:1992] (Rev. Apr.4, 2007) A n n n n a, an; any; one; the same n/adj. iyá ; (suf.) ...-ya ; iyá ki ~ iyá ŋki ~ Abandoned One (A Cultural Hero) Béñe^iñe (I.) [BAY nyeh een nyeh] ~ n iyá ŋke [ee YAH; ee YAHG kee ~ ee YAHG keh] . (NOTE: The word "a, an" is not Béñe^iŋe (O.) [BAY nyeh ing-eh] ; Beré^iŋe ~ Bedé^iŋe (?) . [NOTE: Literally the usually used, except for emphasis or clarity): name may be rendered: “They Abandoned Him Little One” or “The Dear One They This is a boat, Jé^e báje ke. Left Behind”). He is known as Thrown Away or The Outcast in the traditional That is a house, Gá^e chí ke. Wéka n stories. He is said to have been an orphan boy befriended by a chief's son. He There is a man, (O.) Wá nhe iyá n nahé ke. was accused of having an affair with his friend's wife. Abandoned by the whole There is a man, (I.) Wáñe iyá nki nahé ke. community, he was blessed by a shaggy horse that came from the Heavens. At n length, he proves his earnest loyalty to his friend and as a benefactor to his people Do you see any or anyone ? Iyá arásda je. n n and community]. **SEE: Wéka ; Wórage. I have a kitten, Udwáyiñeya áñi ke. n n n n abdomen; torso, trunk, body n. ñixósda sda ~ ñixósta sta [nyee KHOH There was an old man who Wá nša iyá n chí nchiñe stahn stahn] (lit.: “belly round-round”). -

Environment, Cultures, and Social Change on the Great Plains: a History of Crow Creek Tribal School

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2000 Environment, Cultures, and Social Change on the Great Plains: A History of Crow Creek Tribal School Robert W. Galler Jr. Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Galler, Robert W. Jr., "Environment, Cultures, and Social Change on the Great Plains: A History of Crow Creek Tribal School" (2000). Dissertations. 3376. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3376 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENVIRONMENT, CULTURES, AND SOCIAL CHANGE ON THE GREAT PLAINS: A HISTORY OF CROW CREEK TRIBAL SCHOOL by Robert W. Galler, Jr. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillmentof the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 2000 Copyright by Robert W. Galler, Jr. 2000 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people provided assistance, suggestions, and support to help me complete this dissertation. My study of Catholic Indian education on the Great Plains began in Dr. Herbert T. Hoover's American Frontier History class at the University of South Dakota many years ago. I thank him for introducing me to the topic and research suggestions along the way. Dr. Brian Wilson helped me better understand varied expressions of American religious history, always with good cheer. -

Pawnee Tribe, Sioux and the Otoe-Missouri Tribe

Plains Indians By Nicole Kotrous Chapter 1 Plains Indians By Nicole Kotrous Chapter 2 Introduction Years and years ago, buffalo and Indians roamed the plains of North America. It could be that those very buffalo and Indians roamed in your backyard! Imagine... it’s a hot summer night, you’re dashing through the seemingly endless prairie grass. Your bow and arrows bouncing against your back, sweat trickling down your forehead. Your cheeks are blotchy red from running. You look up and meet eyes with a brutal, ferocious animal. You draw your bow, and let the arrow go..swoosh! You have hit the animal. You drop to your knees and begin praying to your one and only God, Wakan Tanka. You thank him for once again feeding your family for another lengthy winter. Plains Indians In the years before European settlers came to the United States, Native American tribes lived all across the land. Several tribes lived in what we call the Plains, or the middle portion of the country. I am going to focus on five Plains Indian tribes. These include: the Ponca tribe, the Omaha tribe, the Pawnee tribe, Sioux and the Otoe-Missouri tribe. Some of these Native- American tribes were nomadic hunters. That means that they traveled all year round in search of plants, animals, food, and fresh water. They also traveled to visit and trade with other tribes. When they traded, they traded for stuff they didn’t have. For example they got horses, shells, beads, and stone that was soft enough to carve, and rock that could be chipped into weapon heads, or points. -

The Skidi Pawnee Morning Star Sacrifice of 1827

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: The Skidi Pawnee Morning Star Sacrifice of 1827 Full Citation: Melburn D Thurman, “The Skidi Pawnee Morning Star Sacrifice of 1827,” Nebraska History 51 (1970): 268-280 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1970MorningStar.pdf Date: 1/13/2012 Article Summary: A traditional Skidi Morning Star sacrifice ceremony was cut short in 1827 when the chief or his son saved the Cheyenne woman who was to be its victim. In doing so the Indians chose not to observe the custom of their tribe but to side with a government agent who had intervened to save the woman. Cataloging Information: Names: Petalesharo, John Dougherty, Big Axe, Joshua Pilcher, Lucien Fontenelle, Alexandre Laforce Papin, Alphonso Wetmore Place Names: Council Bluffs, Fort Atkinson Keywords: Morning Star Sacrifice, Skidi Pawnee, Petalesharo, Knife Chief, John Dougherty, Joshua Pilcher, Lucien Fontenelle, Alexandre Laforce Papin, Big Axe, Alphonso Wetmore Photographs / Images: silver medal awarded to Petalsharo in 1821 because he had intervened to save a Comanche girl, the intended victim of an 1817 Skidi Pawnee Morning Star sacrifice ceremony; a painting of Petalesharo, made while he was in Washington, DC, as a member of a Pawnee deputation in 1821 (painting attributed to Charles B King) " _ " . -

AUTHOR AVAILABLE from the Pawnee Experience

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 235 934 RC 014 310 AUTHOR Solberg, Chris; Goldenstein, Erwin, Ed. TITLE The Pawnee Experience: From Center Village to Oklahoma (Junior High Unit). INSTITUTION Nebraska Univ., Lincoln. Nebraska Curriculum Inst. on Native American Life. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 78 NOTE 80p.; For related document, see RC 014 309. AVAILABLE FROMNebraska Curriculum Development Center, Andrews Hall 32, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68588 0336 ($2.00). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use - Guides (For Teab ers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01\Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS., DESCRIPTORS *American Indian History; American Indian Literature; American Indians; *American Indian Studies; ChronicleS; *Cultural Background; Cultural Education; Cultural Influences; Economic Change; Historiography; Junior High Schools; Kinship; *Learning Modules; *Life Style; Perspective Taking; Primary Sources; *Relocation; Tribes; United States History; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS *Pawnee (Tribe) ABSTRACT A sample packet on the Pawnee experience, developed for use by junior high teachers, includes a\reading list and materials for teachers and students. Sections on Pawnee origins, history, religion and world view, tribal structure and kinship, and economic system before and after relocation from Nebraska to Oklahoma include objectives, lists of materials needed, exercises for students, and essays accompanied by questions to ponder. For _-i-n-stance, the section on Pawnee origins has the following objectives: (1) introducing students to Pawnee accounts of their origins and encounters with Europeans, and to the notion that different people interpret hist6ry differently, according/to their values and history; and (2) showing students that the meaning of history depends in part on the symbolism people carry into a historical event. -

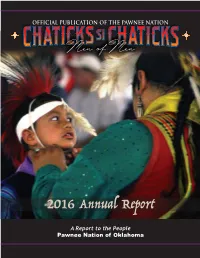

2016 Annual Report

2016 Annual Report A Report to the People Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma In Remembrance... Laureen Sue Eppler Joseph George Ward Jr. 11/24/1959 - 1/3/2016 5/29/74 - 8/22/16 Virginia Mae HorseChief James Vernon Andrews 1/20/1926 - 2/13/2016 9/5/63 - 9/16/16 Estelle Marie “Tiny” Stevens Charles Howlingcrane III 12/30/32 - 3/6/16 8/12/61 - 9/19/16 James Ross Toahty Sherman Herbert Wilde Sr. 7/31/48 - 3/19/16 3/10/31 - 9/21/16 Esther Jean Fields Thomas Neill Bayhylle 11/6/65 - 4/1/16 9/10/43 - 10/1/16 Manny Louis Miller Vernon Lee Hall 6/1/48 - 4/2/16 7/17/44 -10/6/16 Tobias Isaiah Horsechief Howard Ormand John Howell 4/7/16 - 4/7/16 12/23/36 - 11/16/16 Cecil Frank Rouwalk Edith Beardsley 2/14/50 - 4/17/16 3/4/19 - 11/27/16 Arlene Francis Mathews Gibson Scott Sumpter Jr. 5/24/84 - 4/22/16 2/15/59 -12/11/16 Charles James McAllister Sr. James Wayne Blaine 2/14/19 - 4/22/16 1/28/54 -12/11/16 Dennis Michael Sindone Jr. Val Thomas Eppler 11/24/82 - 8/11/16 3/20/57 - 12/17/16 2016 Annual Report of the Pawnee Nation Government to the Pawnee Nation. 2016 Pawnee Business Council Nawa, Building on a legacy of leadership, the Pawnee It is a pleasure serving the Pawnee people on Business Council has eagerly accepted the the Pawnee Business Council and presenting this challenge to protect our lands and our rights to annual report to you. -

Music of the American Indian: Plains: Comanche, Cheyenne, Kiowa

The Library of Congress Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division Recording Laboratory AfS L39 MUSIC OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN PLAINS: COMANCHE, CHEYENNE, KIOWA, CADDO, WICHITA, PAWNEE From the Archive of Folk Culture Recorded and Edited by Willard Rhodes First issued on long-playing record in 1954. Accompanying booklet published 1982. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 82-743369 Available from the Recording Laboratory, Library of Congress, Washington, D .C. 20540. Cover illustration: DANCE OF THE DOG SOLDIER SOCIETIES, by Dick West. Courtesy Philbrook Art Center. Dedicated to the memory of Willard W. Beatty, Director of Indian Education for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Department of the Interior, from 1937 to 1951. • • FOREWORD TO THE 1954 EDITION • • For a number of years the Bureau of Indian Affairs has sponsored the recording of typical Indian music throughout the United States. During this time approximately a thousand Indian songs have been recorded by Mr. Willard Rhodes, professor of music at Columbia Univer sity. The study originated in an effort to deter mine the extent to which new musical themes were continuing to develop. Studies have shown that in areas of Indian concentration, especially in the Southwest, the old ceremonial songs are still used in the traditional fashion. In the Indian areas where assimilation has been greater, Indian type music is still exceedingly popular. There is considerable creative activity in the development of new secular songs which are used for social gatherings. These songs pass from reservation to reservation with slight change. While the preservation of Indian music through recordings contributes only a small part to the total understanding of American Indians, it is nevertheless an important key to this understand ing.