Roger T1." Grange, Jr. a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marsland Class III Cultural Resource Investigation (April 28, 2011)

NRC-054B Submitted: 5/8/2015 I AR CAD IS Marsland Expansion Cultural Inventory I I I I I I I I Figure4. Project overview in Section 35 T30N R51W, facing south. Photograph taken by N. Graves, on 12/02/2010. I I I I I I I I Figure 5. Project overview in Section 2 T29N R51W, facing northeast. Photograph taken by A. Howder on 12/03/2010. I 4 I -1- I ARCADJS Marsland Expansion Cultural Inventory I I I I I I I I I Figure 6. Project overview in Section 1 T29N R51W, facing southeast. Photograph taken by A. Howder on 12/04/2010. I I I I I I I I F. Topographic Map 5 I -2- I AR CAD IS Marsland Expansion Cultural Inventory I V. Environmental Setting I A. Present Environment 1. General Topographic Features I The MEAUP is located in the northern Nebraska Panhandle roughly 10 to 12 miles south of Crawford, Nebraska and five miles northeast of Marsland, Nebraska. This portion of the Nebraska Panhandle is dominated topographically by the Pine Ridge escarpment, a rugged, stony region of forested buttes and I deep canyons that divides the High Plains to the south from the Missouri Plateau to the north. The project area straddles the southernmost boundary of the Pine Ridge escarpment and another distinct topographic region to the south, the Dawes Table lands. Taken together, these regions form a unique local mosaic of I topography, geology, and habitat within the project area. I 2. Project Area a. Topography I The Pine Ridge escarpment covers more than one thousand square miles across far eastern Wyoming, northern Nebraska and extreme southern South Dakota (Nebraska State Historical Society 2000). -

Current Archaeology in Kansas

Current Archaeology in Kansas Number 3 2002 Contents Title and Author(s) Page Empty Quarter Archaeology — Donald J. Blakeslee and David T. Hughes 1 What Lies Beneath: Archeological Investigation of Two Deeply Buried Sites in the Whitewater River Basin — C. Tod Bevitt 5 Ongoing Investigations of the Plains Woodland in Central Kansas — Mark A. Latham 9 A High-Power Use-Wear Analysis of Stone Tools Recovered from 14DO417 — William E. Banks 14 Archaeological Investigation of the Scott Site House (14LV1082) Stranger Creek Valley, Northeastern Kansas, A Progress Report — Brad Logan 20 Kansas Archeology Training Program Field School, 2002 — Virginia A. Wulfkuhle 25 Spatial Variability in Central Plains Tradition Lodges — Donna C. Roper 27 Hit and Run: Preliminary Results of Phase III Test Excavations at 14HO308, a Stratified, Multicomponent, Late Prehistoric Site in Southwest Kansas — C. Tod Bevitt 35 Building a Regional Chronology for Southeast Kansas — H.C. Smith 39 Geoarchaeological Survey of Kirwin National Wildlife Refuge, Northwestern Kansas: Application of GIS Method — Brad Logan, William C. Johnson, and Joshua S. Campbell 44 An Update on the Museum of Anthropology — Mary J. Adair 50 Research Notes: Ceramic Sourcing Study Grant Received — Robert J. Hoard 51 Wallace County Research — Janice A. McLean 52 Another Pawnee Site in Kansas? — Donna C. Roper 53 1 2 Empty Quarter Archaeology Donald J. Blakeslee, Wichita State University David T. Hughes, Wichita State University covered most of the upper end. Furthermore, wind erosion has also created a zone around the When a small survey fails to reveal any lake in which it would be nearly impossible to archaeological sites, it is unusual for someone locate sites even if they were present. -

Indian Trust Asset Appendix

Platte River Endangered Species Recovery Program Indian Trust Asset Appendix to the Platte River Final Environmental Impact Statement January 31,2006 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Denver, Colorado TABLE of CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 The Recovery Program and FEIS ........................................................................................ 1 Indian trust Assets ............................................................................................................... 1 Study Area ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Indicators ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Methods ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Background and History .................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 Overview - Treaties, Indian Claims Commission and Federal Indian Policies .................. 5 History that Led to the Need for, and Development of Treaties ....................................... -

Contemporary Archaeologies of the Southwest P R O C E E D I N G S of the Southwe S T S Y M P O S I U M

Contemporary Archaeologies of the Southwest PRO C EEDING S OF THE SOUTHWE S T S Y M P O S IUM The Archaeology of Regional Interaction: Religion, Warfare, and Exchange across the American Southwest and Beyond EDITED BY MICHELLE HEGMON Contemporary Archaeologies of the Southwest EDITED BY WILLIAM H. WALKER AND KATHRYN R. VENZOR Identity, Feasting, and the Archaeology of the Greater Southwest EDITED BY BARBARA J. MILLS Movement, Connectivity, and Landscape Change in the Ancient Southwest EDITED BY MARGARET C. NELSON AND COLLEEN A. STRAWHACKER Traditions, Transitions, and Technologies: Themes in Southwestern Archaeology EDITED BY SARAH H. SCHLANGER CONTEMPORARY OF ARCHAEOLOGIES THE Edited by William H. Walker and Kathryn R. Venzor U NIVER S I T Y P R E ss O F C O L O R A DO © 2011 by the University Press of Colorado Published by the University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Ad- ams State College, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Mesa State College, Metropolitan State College of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, and Western State College of Colorado. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Southwest Symposium (1988–) (10th : 2006 : Las Cruces, N.M.) Contemporary archaeologies of the Southwest / edited by William H. -

“Sent out by Our Great Father”

“Sent Out By Our Great Father” Zebulon Montgomery Pike’s Journal and Route Across Kansas, 1806 edited by Leo E. Oliva ebulon Montgomery Pike, a lieutenant in the First U.S. Infantry, led an exploring expe- dition in search of the source of the Mississippi River in 1805–1806. Soon after his return to St. Louis in July 1806, General James Wilkinson sent Lieutenant Pike, promoted to cap- tain a few weeks later, to explore the southwestern portion of the Louisiana Purchase, de- parting from the military post of Belle Fontaine near St. Louis on July 15, 1806. His expedition began as Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were nearing completion of their two-year expedition up the Missouri River and across the mountains to the Pacific Ocean and back. Pike crossed present Mis- Zsouri, most of the way by boat on the Missouri and Osage Rivers, where he delivered fifty-one mem- bers of the Osage tribe to the village of the Grand Osage in late August. On September 3 Pike entered present Kansas at the end of the day. His command, including Lieutenant James B. Wilkinson (son of General Wilkinson), Dr. John H. Robinson (civilian surgeon accompanying the ex- pedition), interpreter Antoine François “Baronet” Vásquez (called Baroney in the journal), and eighteen en- listed men, was accompanied by several Osages and two Pawnees as guides. Because of bad feelings between the Osage and Kansa Indians, some of Pike’s Osage guides turned back, and those who continued led his party a Leo E. Oliva, a native Kansan and a former university professor, became interested in frontier military history during the centennial celebration of the founding of Fort Larned in 1959 and has been researching and writing about the frontier army ever since. -

Drawn by the Bison Late Prehistoric Native Migration Into the Central Plains

DRAWN BY THE BISON LATE PREHISTORIC NATIVE MIGRATION INTO THE CENTRAL PLAINS LAUREN W. RITTERBUSH Popular images of the Great Plains frequently for instance, are described as relying heavily portray horse-mounted Indians engaged in on bison meat for food and living a nomadic dramatic bison hunts. The importance of these lifestyle in tune with the movements of the hunts is emphasized by the oft-mentioned de bison. More sedentary farming societies, such pendence of the Plains Indians on bison. This as the Mandan, Hidatsa, Pawnee, Oto, and animal served as a source of not only food but Kansa, incorporated seasonal long-distance also materials for shelter, clothing, contain bison hunts into their annual subsistence, ers, and many other necessities of life. Pursuit which also included gardening. In each case, of the vast bison herds (combined with the multifamily groups formed bands or tribal en needs of the Indians' horses for pasturage) af tities of some size that cooperated with one fected human patterns of subsistence, mobil another during formal bison hunts and other ity, and settlement. The Lakota and Cheyenne, community activities.! Given the importance of bison to these people living on the Great Plains, it is often assumed that a similar pattern of utilization existed in prehistory. Indeed, archeological KEY WORDS: migration, bison, Central Plains, studies have shown that bison hunting was Oneota, Central Plains tradition key to the survival of Paleoindian peoples of the Plains as early as 11,000 years ago. 2 If we Lauren W. Ritterbush is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Kansas State University. -

Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany

Kindscher, L. Yellow Bird, M. Yellow Bird & Sutton Yellow M. Bird, Yellow L. Kindscher, Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany This book describes the traditional use of wild plants among the Arikara (Sahnish) for food, medicine, craft, and other uses. The Arikara grew corn, hunted and foraged, and traded with other tribes in the northern Great Plains. Their villages were located along the Sahnish (Arikara) Missouri River in northern South Dakota and North Dakota. Today, many of them live at Fort Berthold Reservation, North Dakota, as part of the MHA (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara) Ethnobotany Nation. We document the use of 106 species from 31 plant families, based primarily on the work of Melvin Gilmore, who recorded Arikara ethnobotany from 1916 to 1935. Gilmore interviewed elders for their stories and accounts of traditional plant use, collected material goods, and wrote a draft manuscript, but was not able to complete it due to debilitating illness. Fortunately, his field notes, manuscripts, and papers were archived and form the core of the present volume. Gilmore’s detailed description is augmented here with historical accounts of the Arikara gleaned from the journals of Great Plains explorers—Lewis and Clark, John Bradbury, Pierre Tabeau, and others. Additional plant uses and nomenclature is based on the field notes of linguist Douglas R. Parks, who carried out detailed documentation of the Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany tribe’s language from 1970–2001. Although based on these historical sources, the present volume features updated modern botanical nomenclature, contemporary spelling and interpretation of Arikara plant names, and color photographs and range maps of each species. -

Archeological and Bioarcheological Resources of the Northern Plains Edited by George C

Tri-Services Cultural Resources Research Center USACERL Special Report 97/2 December 1996 U.S. Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Construction Engineering Research Laboratory Archeological and Bioarcheological Resources of the Northern Plains edited by George C. Frison and Robert C. Mainfort, with contributions by George C. Frison, Dennis L. Toom, Michael L. Gregg, John Williams, Laura L. Scheiber, George W. Gill, James C. Miller, Julie E. Francis, Robert C. Mainfort, David Schwab, L. Adrien Hannus, Peter Winham, David Walter, David Meyer, Paul R. Picha, and David G. Stanley A Volume in the Central and Northern Plains Archeological Overview Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 47 1996 Arkansas Archeological Survey Fayetteville, Arkansas 1996 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Archeological and bioarcheological resources of the Northern Plains/ edited by George C. Frison and Robert C. Mainfort; with contributions by George C. Frison [et al.] p. cm. — (Arkansas Archeological Survey research series; no. 47 (USACERL special report; 97/2) “A volume in the Central and Northern Plains archeological overview.” Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-56349-078-1 (alk. paper) 1. Indians of North America—Great Plains—Antiquities. 2. Indians of North America—Anthropometry—Great Plains. 3. Great Plains—Antiquities. I. Frison, George C. II. Mainfort, Robert C. III. Arkansas Archeological Survey. IV. Series. V. Series: USA-CERL special report: N-97/2. E78.G73A74 1996 96-44361 978’.01—dc21 CIP Abstract The 12,000 years of human occupation in the Northwestern Great Plains states of Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, and South Dakota is reviewed here. -

1888 Handbook of Concordia

HAND-BOOK )OF(- CONCORDIA AND cloUd county, Kansas CLOUD COUNTY COURT HOUSE, CONCORDIA orEazia^-G-o: C. S. BURCI-I PUBLISHING COMPANY. 1888. ms: r^i J. H. UDELL. E. E. SWEARNGIN. CLOUD COUNTY BANK, SWEARNGIN & UDELL CONCORDIA, KANSAS. REAL ESTATE, LOAN AND INSURANCE, CAPITAL, $100,000. SURPLUS, S^.ooo. Office In Iron Block, T. B. SMITH. PRESCDeNT. W. H. WRIGHT, Vice President. % STURGES, KENNETT £ PECK. Wm. M. PECK. Cashier. C 03STCOK.I3IA., KANSAS. O. B HARRISON, ASST. Cashier. '• Attorneys for the Flank. I*'.J. Atwood, President. G. V.. Latnkov, Cashier. HOWARD HILLIS, C. TC. Sweet, Vice President. W. \V. Bowman, Asst. Cashier. FIRST NATIONAL BANK, ATTORNEY AT LAW COA7CORDIA, KANSAS. CONCORDIA, KANSAS. CAPITAL, SIOO.OOO. SURPLUS, $25,000. Collections made for, and Information furnished to 30x :r,:ec;to:r.s - C. V.. Swekt, Gwi. W. Mahsiiam., Tiieh. I.ai.nt,, C. A. Hktoiknav Eastern Investors. K. J. Atwooii, D. \V. Simmons, Thomas \Vhon«i. W. W. Caldwell, President. J. \V. Pktkkshn, Cashier. L. N. HOUSTON, II. II. McEcKKON, Vice President. 1*. W. Moitr.AN, Asst. Cashier. CITIZENS NATIONAL BANK, REAL ESTATE, LOAN and INSURANCE, CONCORDIA, KANSAS. CONCORDIA, KANSAS. CAPITAL, $100,000. SURPLUS, $7,500. DIRECTORS. J. \V. IV.tkkson, A. Nf.i-son, J. S. Siieak ku, It. H. McEckhon, W. \V. Caldwell, -Correspondence Solicited.- T. H. IlttKKNIAN, JOSKI-II 1'KKHIKK, J. A. KldUY, I). T. DuNN INt;. W. W. CALDWELL, J. W. PETERSON, President Cili/.ens National Rank. Cashier Citizens National Rank. Real Estate Agent and Loan Broker, CALDWELL & PETERSON, Negotiators of Loans. CONCORDIA, KANSAS. Ten vcars' experience. -

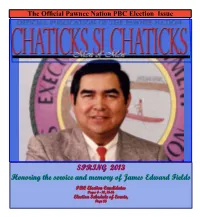

Honoring the Service and Memory of James Edward Fields

The Official Pawnee Nation PBC Election Issue spring 2013 Honoring the service and memory of James Edward Fields pBC Election Candidates pages 4 - 10, 15-16 Election schedule of Events, page 23 Page 2 Chaticks si Chaticks - spring 2013 Pawnee Business Nawah! COuncil Greetings all of you fellow Paw- nee Tribal Members! President: We were saddened by the news of Marshall Gover the passing of Council Member Jim Fields. Our heart goes out to his family Vice President: and all of his relations. We will miss Charles “Buddy” Lone Chief him dearly. It goes to show we never know when Atius will call our name Secretary: home. I want to wish all of our people Linda Jestes good travels and may Atius smile upon you on your adventures. Treasurer: It is coming time for elections and Acting, Linda Jestes we are wishing all those who are run- ning in the upcoming Pawnee Business Council elections the best of luck. For Council Seat 1: those of us who have to decide who to Richard Tilden vote for, I hope that you will give each and every candidate their due respect Council Seat 2: and look at each of their qualifications Karla Knife Chief and abilities. Being on the Business Council is a strong responsibility. We Council Seat 3: sometimes think that when we get on Vacant the Pawnee Tribal Council, we can do so many things, but we need to realize that we are only one vote. We need to make sure what we do for the Pawnee people is in their best interest. -

Streamflow Depletion Investigations in the Republican River Basin: Colorado, Nebraska, and Kansas

J. ENVIRONMENTAL SYSTEMS, Vol. 27(3) 251-263, 1999 STREAMFLOW DEPLETION INVESTIGATIONS IN THE REPUBLICAN RIVER BASIN: COLORADO, NEBRASKA, AND KANSAS JOZSEF SZILAGYI University of Nebraska–Lincoln ABSTRACT Water is a critical resource in the Great Plains. This study examines the changes in long-term mean annual streamflow in the Republican River basin. In the past decades this basin, shared by three states, Colorado, Nebraska, and Kansas, displayed decreased streamflow volumes as the river enters Kansas across the Nebraska-Kansas border compared to values preceding the 1950s. A recent lawsuit filed by Kansas challenges water appropriations in Nebraska. More than half of the source area for this water, however, lies outside of Nebraska. Today a higher percentage of the annual flow is generated within Nebraska (i.e., 75% of the observed mean annual stream- flow at the NE-KS border) than before the 1950s (i.e., 66% of the observed mean annual streamflow) indicating annual streamflow has decreased more dramatically outside of Nebraska than within the state in the past fifty years. INTRODUCTION The Republican River basin’s 64,796 km2 drainage area is shared by three states: Colorado, Nebraska, and Kansas (see Figure 1). Nebraska has the largest single share of the drainage area, 25,154 km2 (39% of total); Colorado can claim about 20,000 km2 (31%), while the rest, about 19,583 km2 (30%), belongs to Kansas [1], from which about 12,800 km2 (20%) lies upstream of Hardy, near the Nebraska-Kansas border. Exact figures for the contributing drainage areas (portions of the drainage areas that actually contribute water to the stream) are hard to obtain because these areas in the headwater sections of the basin have been shrinking constantly in the past fifty years. -

For-Hire Motor Carriers-Unrestricted Property

For-Hire - Unrestricted Property September 23, 2021 PIN USDOT MC Name DBA Name Phone Street Suite City State Zip 172318 2382342 1ST CALL HOTSHOT SERVICE LLC 1ST CALL HOTSHOT SERVICE LLC (405) 205-1738 Mail: 2410 W MEMORIAL RD STE C533 OKLAHOMA CITY OK 73134 Physical: 406 6TH ST CHEYENNE OK 73628 106139 1129401 2 B TRUCKING LLC 2 B TRUCKING LLC (936) 635-1288 Mail: 1430 N TEMPLE DIBOLL TX 75941 Physical: 214671 3131628 2 K SERVICES LLC 2 K SERVICES LLC (405) 754-0351 Mail: 2305 COUNTY ROAD 1232 BLANCHARD OK 73010 Physical: 142776 587437 2 R TRUCKING LLC 2 R TRUCKING LLC (402) 257-4105 Mail: 1918 ROAD ""P"" GUIDE ROCK NE 68942 Physical: 152966 2089295 2 RIVERS CONVERSIONS LLC 2 RIVERS CONVERSIONS LLC (405) 380-6771 Mail: 3888 N 3726 RD HOLDENVILLE OK 74848 Physical: 227192 3273977 2 VETS TRUCKING LLC 2 VETS TRUCKING LLC (405) 343-3468 Mail: 9516 TATUM LANE OKLAHOMA CITY OK 73165 Physical: 250374 3627024 2A TRANSPORT LLC 2A TRANSPORT LLC (918) 557-4000 Mail: PO BOX 52612 TULSA OK 74152 Physical: 10055 E 590 RD CATOOSA OK 74015 144063 1885218 3 C CATTLE FEEDERS INC 3 C CATTLE FEEDERS INC (405) 947-4990 Mail: PO BOX 14620 OKLAHOMA CITY OK 73113 Physical: PO BOX 144 MILL CREEK OK 74856 193972 2881702 3 CASAS TRUCKING LLC 3 CASAS TRUCKING LLC (405) 850-0223 Mail: 3701 KEITH COURT OKLAHOMA CITY OK 73135 Physical: 3701 KEITH COURT OKLAHOMA CITY OK 73135 251354 3678453 3 FEATHERS LOGISTICS LLC 3 FEATHERS LOGISTICS LLC (918) 991-4528 Mail: 411 N HODGE ST SAPULPA OK 74066 Physical: 134041 1728299 3 LANE TRUCKING LLC 3 LANE TRUCKING LLC Mail: RR1