Making National Museums: Comparing Institutional Arrangements, Narrative Scope and Cultural Integration (Namu)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making National Museums: Comparing Institutional Arrangements, Narrative Scope and Cultural Integration (Namu)

NaMu Making National Museums: Comparing institutional arrangements, narrative scope and cultural integration (NaMu) NaMu IV Comparing: National Museums, Territories, Nation-Building and Change Linköping University, Norrköping, Sweden 18–20 February 2008 Conference Proceedings Editors Peter Aronsson and Andreas Nyblom Financed by the European Union Marie Curie Conferences and Training Courses http://cordis.europa.eu/mariecurie-actions/ NaMu. Contract number (MSCF-CT-2006 - 046067) Copyright The publishers will keep this document online on the Internet – or its possible replacement – for a period of 25 years starting from the date of publication barring exceptional circumstances. The online availability of the document implies permanent permission for anyone to read, to download, or to print out single copies for his/her own use and to use it unchanged for non- commercial research and educational purposes. Subsequent transfers of copyright cannot revoke this permission. All other uses of the document are conditional upon the consent of the copyright owner. The publisher has taken technical and administrative measures to assure authenticity, security and accessibility. According to intellectual property law, the author has the right to be mentioned when his/her work is accessed as described above and to be protected against infringement. For additional information about Linköping University Electronic Press and its procedures for publication and for assurance of document integrity, please refer to its www home page: http://www.ep.liu.se/. -

Architecture: the Museum As Muse Museum Education Program for Grades 6-12

Architecture: The Museum as Muse Museum Education Program for Grades 6-12 Program Outline & Volunteer Resource Package Single Visit Program Option : 2 HOURS Contents of Resource Package Contents Page Program Development & Description 1 Learning Objectives for Students & Preparation Guidelines 2 One Page Program Outline 3 Powerpoint Presentation Overview 4 - 24 Glossary – Architectural Terms 24 - 27 Multimedia Resource Lists (Potential Research Activities) 27 - 31 Field Journal Sample 32 - 34 Glossary – Descriptive Words Program Development This programme was conceived in conjunction with the MOA Renewal project which expanded the Museum galleries, storages and research areas. The excitement that developed during this process of planning for these expanded spaces created a renewed enthusiasm for the architecture of Arthur Erickson and the landscape architecture of Cornelia Oberlander. Over three years the programme was developed with the assistance of teacher specialists, Jane Kinegal, Cambie Secondary School and Russ Timothy Evans, Tupper Secondary School. This programme was developed under the direction of Jill Baird, Curator of Education & Public Programmes, with Danielle Mackenzie, Public Programs & Education Intern 2008/09, Jennifer Robinson, Public Programs & Education Intern 2009/10, Vivienne Tutlewski, Public Programs & Education Intern 2010/2011, Katherine Power, Public Programs & Education Workstudy 2010/11, and Maureen Richardson, Education Volunteer Associate, who were all were key contributors to the research, development and implementation of the programme. Program Description Architecture: The Museum as Muse, Grades 6 - 12 MOA is internationally recognized for its collection of world arts and culture, but it is also famous for its unique architectural setting. This program includes a hands-on phenomenological (sensory) activity, an interior and exterior exploration of the museum, a stunning visual presentation on international museum architecture, and a 30 minute drawing activity where students can begin to design their own museum. -

Museum Air. the Art of Handling Art

lifefeb/2 0 13 magazine Museum air. The art of handling art. contents viewpoint lifefeb/2 0 13 magazine project report Museum buildings. The art of handling art. Page 4 science & technology Art pour l’art. In line with our slogan, we turn to the arts or much more, their place of collection Museum air. Page 10 The art of handling art. or assembly. For in recent decades, very impressive museum buildings have been erected: The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the Tate Modern in London, the feature Acropolis Museum in Athens, the Museum Folkwang in Essen or the very recent The Da Vinci Code. National Museum of China in Beijing. Page 18 Visit with us the world‘s most beautiful, most interesting and most famous museums highlights where we offer insight into the ventilation characteristics of museum buildings. Museums. Page 24 We have also „met“ a fascinating person generally regarded as the universal genius par excellence: Leonardo da Vinci. He is the forefather of fluid dynamics as is evident highlights from his sketchbooks, which were only rediscovered in the 60s of the last century. Museological. Scientists of our time have duplicated, for example, a diving suit and a flying glider from Page 26 his sketches and proven that his technical inventions work. forum & economy And last but not least, read some news about TROX. With the acquisition of the Art at its best economically. TLT building fans, the line of ventilation systems comes full circle for TROX. We can Page 28 now offer our customers the heart of ventilation technology, the fan. -

Open Windows 10

Leticia de Cos Martín Martín Cos de Leticia Beckmann Beckmann Frau than Quappi, much more more much Quappi, pages 47 — 64 47 — 64 pages Clara Marcellán Marcellán Clara in California in California Kandinsky and Klee Klee and Kandinsky of Feininger, Jawlensky, Jawlensky, of Feininger, and the promotion promotion the and Galka Scheyer Galka Scheyer ‘The Blue Four’: Four’: Blue ‘The pages 34 — 46 34 — 46 pages Manzanares Manzanares Juan Ángel Lpez- Ángel Juan ~' of modern art as a collector as a collector Bornemisza’s beginnings beginnings Bornemisza’s - ~~.·;•\ Thyssen Baron On ~ .. ;,~I il~ ' r• , ~.~ ··v,,,:~ ' . -1'\~J"JJj'-': . ·'-. ·•\.·~-~ . 13 — 33 pages Nadine Engel Engel Nadine Expressionist Collection Collection Expressionist Thyssen-Bornemisza’s German German Thyssen-Bornemisza’s Beginning of Hans Heinrich Heinrich Hans of Beginning 1, 1 ~- .,.... Museum Folkwang and the the and Folkwang Museum ,..~I,.. '' i·, '' ·' ' ' .·1,.~.... Resonance Chamber. Chamber. Resonance . ~I•.,Ji'•~-., ~. pages 2 — 12 2 — 12 pages ~ -~~- . ., ,.d' .. Ali. .~ .. December 2020 2020 December 10 10 Open Windows Windows Open Open Windows 10 Resonance Chamber. Museum Folkwang and the Beginning of Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’s German Expressionist Collection Nadine Engel Emil Nolde Young Couple, c. 1931–35 22 HollandischerDirektor bracht ✓ Thyssen-Schatzenach Essen Elnen kaum zu bezifiernden Wert bat elne Ausslellung des Folkwang-Museums, die btszum 20. Marz gezelgt wird: sie ent hiilt hundertzehn Melsterwerke der europaisdlen Malerei des 14. bis 18. Jahrhunderts aus der beriihmten Sammlung Sdtlo8 Roboncz, die heute Im Besitz des nodt Jungen Barons H. H. Thys sen-Bornemisza ist und in der Villa Favorlta bei Lugano ihr r Domlzil hat. Insgesamt mnfafll sie 350 Arbeiten. -

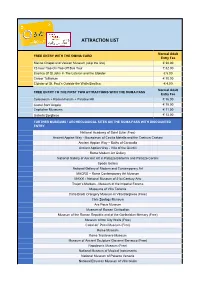

Attraction List

ATTRACTION LIST Normal Adult FREE ENTRY WITH THE OMNIA CARD Entry Fee Sistine Chapel and Vatican Museum (skip the line) € 30.00 72-hour Hop-On Hop-Off Bus Tour € 32.00 Basilica Of St.John In The Lateran and the Cloister € 5.00 Carcer Tullianum € 10.00 Cloister of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls Basilica € 4.00 Normal Adult FREE ENTRY TO THE FIRST TWO ATTRACTIONS WITH THE ROMA PASS Entry Fee Colosseum + Roman Forum + Palatine Hill € 16.00 Castel Sant’Angelo € 15.00 Capitoline Museums € 11.50 Galleria Borghese € 13.00 FURTHER MUSEUMS / ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES ON THE ROMA PASS WITH DISCOUNTED ENTRY National Academy of Saint Luke (Free) Ancient Appian Way - Mausoleum of Cecilia Metella and the Castrum Caetani Ancient Appian Way – Baths of Caracalla Ancient Appian Way - Villa of the Quintili Rome Modern Art Gallery National Gallery of Ancient Art in Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Corsini Spada Gallery National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art MACRO – Rome Contemporary Art Museum MAXXI - National Museum of 21st Century Arts Trajan’s Markets - Museum of the Imperial Forums Museums of Villa Torlonia Carlo Bilotti Orangery Museum in Villa Borghese (Free) Civic Zoology Museum Ara Pacis Museum Museum of Roman Civilization Museum of the Roman Republic and of the Garibaldian Memory (Free) Museum of the City Walls (Free) Casal de’ Pazzi Museum (Free) Rome Museum Rome Trastevere Museum Museum of Ancient Sculpture Giovanni Barracco (Free) Napoleonic Museum (Free) National Museum of Musical Instruments National Museum of Palazzo Venezia National Etruscan -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 712 Friday No. 106 10 July 2009 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDER OF BUSINESS Arrangement of Business Announcement Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies and Credit Unions Bill Second Reading Autism Bill Second Reading Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) Bill Second Reading Driving Instruction (Suspension and Exemption Powers) Bill Second Reading Written Answers For column numbers see back page £3·50 Lords wishing to be supplied with these Daily Reports should give notice to this effect to the Printed Paper Office. The bound volumes also will be sent to those Peers who similarly notify their wish to receive them. No proofs of Daily Reports are provided. Corrections for the bound volume which Lords wish to suggest to the report of their speeches should be clearly indicated in a copy of the Daily Report, which, with the column numbers concerned shown on the front cover, should be sent to the Editor of Debates, House of Lords, within 14 days of the date of the Daily Report. This issue of the Official Report is also available on the Internet at www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200809/ldhansrd/index/090710.html PRICES AND SUBSCRIPTION RATES DAILY PARTS Single copies: Commons, £5; Lords £3·50 Annual subscriptions: Commons, £865; Lords £525 WEEKLY HANSARD Single copies: Commons, £12; Lords £6 Annual subscriptions: Commons, £440; Lords £255 Index—Single copies: Commons, £6·80—published every three weeks Annual subscriptions: Commons, £125; Lords, £65. LORDS CUMULATIVE INDEX obtainable on standing order only. Details available on request. BOUND VOLUMES OF DEBATES are issued periodically during the session. -

GOLDSCHMIED & CHIARI Sara Goldschmied (B. 1975, Arzignano

GOLDSCHMIED & CHIARI Sara Goldschmied (b. 1975, Arzignano, Italy) and Eleonora Chiari (b. 1971, Rome, Italy) Live and work in Milan, Italy SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 International Arts & Artists at Hillyer, Washington, DC (forthcoming) 2019 Goldschmied & Chiari: Paesaggi artificiali, curated by Gaspare Luigi Marcone, Galleria Poggiali, Milan, Italy Goldschmied & Chiari, curated by Gaspare Luigi Marcone, Galleria Poggiali, Pietrasanta, Italy Goldschmied & Chiari: Eclisse, curated by Gaspare Luigi Marcone, Museo Novecento, Florence, Italy 2018 Secret Eyes Only, Doppelgaenger, Bari, Italy Fumo Negli Occhi, curated by Roberto Lacarbonara, ExChiesetta, Polignano a Mare, Italy 2017 Vice Versa, Kristen Lorello, New York, NY Untitled Views, Renata Fabbri Arte Contemporanea, Milan, Italy 2014 Goldschmied & Chiari: Untitled Portraits, Kristen Lorello, New York, NY La democrazia è illusione, curated by Ilaria Bonacossa, Villa Croce, Museum of Contemporary Art, Genova (IT) La démocratie est illusion, curated by Etienne Bernard, Centre d’Art Contemporaine Passerelle, Brest (FR) 2013 Hiding the Elephant, Edicola Notte, Rome, (IT) 2011 Nympheas, curated by Paola Ugolini and Camilla Grimaldi, Icario Arte, Montepulciano, (IT) 2010 Fumo negli occhi, Gonzalez y Gonzalez Gallery, Santiago, Chile Genealogy of Damnatio Memoriae, Atelier House, Museion Museum of contemporary art, Bolzano, (IT) 2009 Roommates, curated by Cecilia Canziani, Macro Museum of contemporary art, Rome, (IT) 2008 Dump Queen, Galerie Elaine Levy Project, Bruxelles, (BE) Dump Queen, curated -

Beatboxing, Rap, and Spoken Word

Learning Resource Pack Beatboxing, rap, and spoken word Creating contemporary music and lyrics inspired by culture and heritage. Contents 03 Introduction 04 Using collections and heritage to inspire contemporary artwork 06 About contemporary beatbox, rap and spoken word 08 Planning your project 14 Methods — Method 1: Creating rap lyrics — Method 2: Beatboxing techniques — Method 3: Creating spoken word and poetry 18 Casestudies — Case study 1: Welsh language with key stage 2 — Ysgol Pentraeth, National Slate Museum, Mr Phormula, and Bari Gwilliam — Case study 2: Beatboxing and rap, English language with key stage 3 — Lewis School Pengam, Big Pit and Beat Technique — Case study 3: Bilingual with key stage 3 — Tredegar Park School, Tredegar House (National Trust), and Rufus Mufasa 25 Extending the learning and facilitating curriculum learning 26 Nextsteps 26 Digital resources 27 Abouttheauthors Arts & Education Network; South East Wales 2 Beatboxing, rap, and spoken word Introduction This creative lyric and music project has The projects in this resource can be been tried and tested with schools by the simplified, adapted or further developed authors Rufus Mufasa, Beat Technique and to suit your needs. There are plenty of Mr Phormula. The project is designed to be opportunities for filmmaking, recording pupil-centred, fun, engaging, relevant and and performing, all of which help to in-line with the Welsh Government Digital develop wider creative attributes Competence Framework, while exploring including resilience, presentation skills, pupil’s individual creativity through the communication skills, and collaboration Expressive Arts Curriculum framework, and that are so important to equip learners facilitating the curriculum’s Four Purposes. -

Museums, Galleries & Heritage Careers

Museums, Galleries & Heritage Careers The heritage sector covers museums, science centres, heritage Produced with the support of the organisations, buildings, archaeology, archives and conservation. Find Museums Association. Last updated March 2021 out what your options are, how to get your foot in the door and where to look for vacancies. Opportunities in the sector Job roles: Information/library/archives – Curation – overall responsibility for a record and facilitate use of collection of artefacts or works of art. materials by the institution’s clients They acquire, research, display and Digital – engaging audiences and write about objects making collections and stories Collections – managing objects, accessible online preserving documentation, Volunteer management – cataloguing, storage, preventative organising volunteers and ensuring care, lighting, digital recording a positive experience Conservation – making sure things Partnerships - securing Types of employment: are stable, safe and in good condition sponsorships and partnerships with There is no one path into a museums or before being displayed or leant. Often a wide range of brands and heritage career. Lots of people start out in specialise in a type of object e.g. companies to support the the sector through volunteering, and some paintings or furniture organisations work continue to develop their skills and Learning – education, outreach, Science communication – making networks by volunteering even when they community events. Preparation and scientific content understandable are employed. The heritage sector has delivery of programmes, events and and accessible become increasingly dependent on resources for schools and other Research - conducting research in volunteers to maintain services, and visitors scientific, cultural, historical, or volunteers become very professional and Exhibitions – organising specific artistic fields for use in projects skilled. -

The Government Information Landscape and Libraries

IFLA Professional Report No.137 The Government Information Landscape and Libraries Edited by: Kay Cassell, James Church and Kathryn Tallman, with editorial assistance from Carol Church Cover Photo: Portion of the Government Documents collection held in the Reading Room at the Main Library. Photo taken on 9 September 2014 by CECrane. Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0). University of Illinois. Kay Cassell, Nera Kimar, Clive Tsuma, Susan Paterson, Mohammad Zuheir Bakleh, Lize Denner, Anna Mastora, Maria Koloniari, Maria Monopoli, James Church, Jungwon Yang, Anastasia A. Drozdova, Hannah Chandler, Jennie Grimshaw, Kian Flynn, Cass Hartnett, Maya Swanes, Robert Loprest, Kathryn Tallman, United Nations Cybersecurity Section, & World Bank Group ITS Office of Information Security, 2021. The Government Information Landscape and Libraries/ Edited by Kay Cassell, James Church and Kathyrn Tallman, with editorial assistance from Carol Church The Hague, IFLA Headquarters, 2021. – 161 p. (IFLA Professional Reports: 137) ISBN 978-90-77897-75-1 ISSN 0168-1931 © 2021 by IFLA. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license. To view a copy of this license visit: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 IFLA P.O. Box 95312 2509 CH Den Haag Netherlands www.ifla.org 1 Introduction 3 Dr. Kay Cassell, School of Communication and Information, Rutgers University Complexity of the Government Information Landscape in Sub-Saharan Africa 7 Nerisa Kamar, Information Africa Organization, Kenya, & Dr. Clive Tsuma, -

National Museums in Poland Kazimierz Mazan

Building National Museums in Europe 1750-2010. Conference proceedings from EuNaMus, European National Museums: Identity Politics, the Uses of the Past and the European Citizen, Bologna 28-30 April 2011. Peter Aronsson & Gabriella Elgenius (eds) EuNaMus Report No 1. Published by Linköping University Electronic Press: http://www.ep.liu.se/ecp_home/index.en.aspx?issue=064 © The Author. National Museums in Poland Kazimierz Mazan Summary The patterns that museums in Poland, and other European countries, developed bear many similarities, however, in Poland's case, the main determining factor appears to be the political situation in Eastern Europe. The author shall present the history of museum evolution, in relation to nation-state-generative processes, using a four-stage periodic division: the Partitions (1795-1918), restored independence (1918-1939), realsocializmus (1945-1989), and the new democracy (1989-2010). The first initiatives in favour of creating museums appeared in the first period, following the annexation of Polish territories by Russia, Prussia, and Austria, and were predominantly of grassroots character. The driving force behind them consisted mainly of private collectors or associations thereof. The first museum conceived as ‘national’ in the sense of public, and full accessibility (not in the sense of state ownership), was instituted in Krakow by the local municipal authorities, as the National Museum in Krakow. It was the first case in a mass of private collections and museums that had hitherto dominated the landscape. The second period – of regained national independence – spanning the time between the two world wars, was marked mostly by the influence exerted by newly-founded, central state agencies, aiming at steering museums towards a more nationalistic path: propagating petrifying the ‘Polish spirit’ in Polish territories which continued to be inhabited by a multitude of diverse nationalities. -

National Museums in Spain: a History of Crown, Church and People José María Lanzarote Guiral

Building National Museums in Europe 1750-2010. Conference proceedings from EuNaMus, European National Museums: Identity Politics, the Uses of the Past and the European Citizen, Bologna 28-30 April 2011. Peter Aronsson & Gabriella Elgenius (eds) EuNaMus Report No 1. Published by Linköping University Electronic Press: http://www.ep.liu.se/ecp_home/index.en.aspx?issue=064 © The Author. National Museums in Spain: A History of Crown, Church and People José María Lanzarote Guiral Summary The present report provides an overview on the history of national museums in Spain as well as an analysis of a selected set of case studies. In the first part of this report, a historical outline of the creation and evolution of museums is provided from the point of view of the enlarging scope of the concept ‘national heritage’. The choice of national museums in the second part exemplifies the role played by different categories of heritage in the construction of national master narrative in Spain, including fine arts (Museo del Prado), archaeology (Museo Arqueológico Nacional) and nature (Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales). The study of the Museum of the Americas (Museo de América) allows for the exploration of the complex relationship between Spanish national identity and the imperial past, whereas the Museum of History of Catalonia (Museu d’Història de Catalunya) leads reflection to the competing nationalist projects within the state. Finally, the case of the Museum of the Spanish Army (Museo del Ejército Español) is considered in the light of the contemporary debates on ‘historical memory’ that have marked its recent renovation. 847 Summary table, Spain Name Inaugurated Initiated Actors Ownership Type Values Temporal reach Style Location Prado Museum 1819 1819 Crown, Royal (1819-68) Fine Arts Spanish and Classical to Originally purpose-built Museo Nacional del Spanish state State (1868-) (painting and universal Neoclassical for Museum of Natural Prado sculpture) (sculpture) Sciences Middle Ages to (1785-1819), beginning 19th c.