National Museums in Poland Kazimierz Mazan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scenario of the Exhibition: Tomasz Łabuszewski, Phd, in Cooperation with Anna Maria Adamus, Phd, Ewa Dyngosz, Edyta Gula and Michał Zarychta

STOLEN CHILDHOOD Scenario of the exhibition: Tomasz Łabuszewski, PhD, in cooperation with Anna Maria Adamus, PhD, Ewa Dyngosz, Edyta Gula and Michał Zarychta Graphic design: Katarzyna Dinwebel Reviewers: Bartosz Kuświk, PhD Waldemar Brenda, PhD Producer: Pracownia Plastyczna Andrzej Dąbrowski Photographs from the following archives: AKG images, Archive of the Institute of National Remembrance, Municipal Archive in Dzerzhinsk, State Archive in Warsaw, Archive of Polish Armenians, BE&W Foto, National Library, Bundesarchiv, Centre for Documentation of Deportations, Exile and Resettlements in Cracow, Foundation for Polish-German Reconciliation, Getty Images, Museum of the Second World War, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Polish Army Museum in Kołobrzeg, Warsaw Rising Museum, Regional Museum in Jarocin, Museum of the Castle of Górka Family in Szamotuły, National Digital Archive, Ośrodek Karta, Polish Photographers’ Agency Forum, Polish Press Agency, Underground Poland Studio, Documentary and Feature Film Studio, Association of Crimean Karaites in Poland. With special thanks to: Bogdan Bednarczyk, Janusz Bogdanowicz, Alina Głowacka-Szłapowa, Tomasz Karasiński, Kazimierz Krajewski, PhD, Ewa Siemaszko and Leszek Żebrowski, as well as the Institute of National Remembrance branch offices in Łódź and Poznań. Photograph on the front panel: Archives of the Institute of National Remembrance Despite their efforts, the authors of the exhibition did not manage to reach all authors of photographs used in the exhibition or holders of proprietary -

They Fought for Independent Poland

2019 Special edition PISMO CODZIENNE Independence Day, November 11, 2019 FREE AGAIN! THEY FOUGHT FOR INDEPENDENT POLAND Dear Readers, The day of November 11 – the National Independence Day – is not accidentally associated with the Polish military uni- form, its symbolism and traditions. Polish soldiers on almost all World War I fronts “threw on the pyre their lives’ fate.” When the Polish occupiers were drown- ing in disasters and revolutions, white- and-red flags were fluttering on Polish streets to mark Poland’s independence. The Republic of Poland was back on the map of Europe, although this was only the beginning of the battle for its bor- ders. Józef Piłsudski in his first order to the united Polish Army shared his feeling of joy with his soldiers: “I’m taking com- mand of you, Soldiers, at the time when the heart of every Pole is beating stron- O God! Thou who from on high ger and faster, when the children of our land have seen the sun of freedom in all its Hurls thine arrows at the defenders of the nation, glory.” He never promised them any bat- We beseech Thee, through this heap of bones! tle laurels or well-merited rest, though. On the contrary – he appealed to them Let the sun shine on us, at least in death! for even greater effort in their service May the daylight shine forth from heaven’s bright portals! for Poland. And they never let him down Let us be seen - as we die! when in 1920 Poland had to defend not only its own sovereignty, but also entire Europe against flooding bolshevism. -

Warsaw Nno.O

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels Warsaw NNo.o. 882,2, AAugustugust - SSeptembereptember 22014014 The Warsaw Uprising Awe Inspiring - 70 Years On inyourpocket.com ł No. 82 - 5z ȱȱ¢ȱȱȱ ȱȱ¢ȱȱ ȱȱȱȱ ȱ ȱȱĴȱȱ ǯȱȱŝǰȱ£ ȱǯǯǯȱ ǯȱŘŘȱŞŚŞȱŗŘȱŘśǰȱǯȦ¡ȱŘŘȱŞŚŞȱŗśȱşŖ ǯǯǯȱȱ ȱȱȱ ǯ£ǯǯ ǯ ȱ ȱȱȱȱȱǰȱ¢ȱȱ ȱȱ ȱȱȱ ȱȱȱ ȱȱ¢ȱ ȱ ȱ Ěȱȱȱȱ¢ȱ¢ǯ ȱȱȱȱȱȱȱ dz Contents Feature Further Afi eld Warsaw Uprising 8 Łódź 106 Arrival & Transport 12 Leisure 108 City Basics 18 Shopping 112 Culture & Events 20 Directory 118 Restaurants 26 Hotels 120 Cafés 57 Maps & Index Street Index 124 Nightlife 58 City Centre Map 125 Sightseeing City Map 126-127 Essential Warsaw 71 Country Map 128 Sightseeing 72 Listings Index 129 Old Town 84 The Royal Route 87 Features Index 130 Palace of Culture and Science 89 Praga 90 Copernicus Science Center 92 Łazienki 94 IN PRINT Wilanów 97 Jewish Warsaw 100 ONLINE Chopin 103 ON YOUR MOBILE PLAC TEATRALNY 3, WARSAW TEL. +48 601 81 82 83 Monument to the Warsaw Uprising Photo by Zbigniew Furman. Courtesy of Warsaw Uprising Museum. [email protected] 4 Warsaw In Your Pocket warsaw.inyourpocket.com Foreword Welcome to Warsaw and the 82nd edition of Warsaw Publisher In Your Pocket! Summer is in full swing and the city is IYP City Guides Sp. z o.o. Sp.k. absolutely sizzling. It’s the perfect time to take advantage ul. Sławkowska 12, 31-014 Kraków the capitals’ many fi ner points - exploring the parks, [email protected] gardens (beer) and breathtaking urban riverwalks (take www.inyourpocket.com a walk on the wild side!). -

Warsaw in Short

WarsaW TourisT informaTion ph. (+48 22) 94 31, 474 11 42 Tourist information offices: Museums royal route 39 Krakowskie PrzedmieÊcie Street Warsaw Central railway station Shops 54 Jerozolimskie Avenue – Main Hall Warsaw frederic Chopin airport Events 1 ˚wirki i Wigury Street – Arrival Hall Terminal 2 old Town market square Hotels 19, 21/21a Old Town Market Square (opening previewed for the second half of 2008) Praga District Restaurants 30 Okrzei Street Warsaw Editor: Tourist Routes Warsaw Tourist Office Translation: English Language Consultancy Zygmunt Nowak-Soliƒski Practical Information Cartographic Design: Tomasz Nowacki, Warsaw Uniwersity Cartographic Cathedral Photos: archives of Warsaw Tourist Office, Promotion Department of the City of Warsaw, Warsaw museums, W. Hansen, W. Kryƒski, A. Ksià˝ek, K. Naperty, W. Panów, Z. Panów, A. Witkowska, A. Czarnecka, P. Czernecki, P. Dudek, E. Gampel, P. Jab∏oƒski, K. Janiak, Warsaw A. Karpowicz, P. Multan, B. Skierkowski, P. Szaniawski Edition XVI, Warszawa, August 2008 Warsaw Frederic Chopin Airport Free copy 1. ˚wirki i Wigury St., 00-906 Warszawa Airport Information, ph. (+48 22) 650 42 20 isBn: 83-89403-03-X www.lotnisko-chopina.pl, www.chopin-airport.pl Contents TourisT informaTion 2 PraCTiCal informaTion 4 fall in love wiTh warsaw 18 warsaw’s hisTory 21 rouTe no 1: 24 The Royal Route: Krakowskie PrzedmieÊcie Street – Nowy Âwiat Street – Royal ¸azienki modern warsaw 65 Park-Palace Complex – Wilanów Park-Palace Complex warsaw neighborhood 66 rouTe no 2: 36 CulTural AttraCTions 74 The Old -

Making National Museums: Comparing Institutional Arrangements, Narrative Scope and Cultural Integration (Namu)

NaMu Making National Museums: Comparing institutional arrangements, narrative scope and cultural integration (NaMu) NaMu IV Comparing: National Museums, Territories, Nation-Building and Change Linköping University, Norrköping, Sweden 18–20 February 2008 Conference Proceedings Editors Peter Aronsson and Andreas Nyblom Financed by the European Union Marie Curie Conferences and Training Courses http://cordis.europa.eu/mariecurie-actions/ NaMu. Contract number (MSCF-CT-2006 - 046067) Copyright The publishers will keep this document online on the Internet – or its possible replacement – for a period of 25 years starting from the date of publication barring exceptional circumstances. The online availability of the document implies permanent permission for anyone to read, to download, or to print out single copies for his/her own use and to use it unchanged for non- commercial research and educational purposes. Subsequent transfers of copyright cannot revoke this permission. All other uses of the document are conditional upon the consent of the copyright owner. The publisher has taken technical and administrative measures to assure authenticity, security and accessibility. According to intellectual property law, the author has the right to be mentioned when his/her work is accessed as described above and to be protected against infringement. For additional information about Linköping University Electronic Press and its procedures for publication and for assurance of document integrity, please refer to its www home page: http://www.ep.liu.se/. -

Discover Warsaw

DISCOVER WARSAW #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw #discoverwarsaw WELCOME TO WARSAW! If you are looking for open people, fascinating history, great fun and unique flavours, you've come to the right place. Our city offers you everything that will make your trip unforgettable. We have created this guide so that you can choose the best places that are most interesting for you. The beautiful Old Town and interactive museums? The wild river bank in the heart of the city? Cultural events? Or maybe pulsating nightlife and Michelin-star restaurants? Whatever your passions and interests, you'll find hundreds of great suggestions for a perfect stay. IT'S TIME TO DISCOVER WARSAW! CONTENTS: 1. Warsaw in 1 day 5 2. Warsaw in 2 days 7 3. Warsaw in 3 days 11 4. Royal Warsaw 19 5. Warsaw fights! 23 6. Warsaw Judaica 27 7. Fryderyk Chopin’s Warsaw 31 8. The Vistula ‘District’ 35 9. Warsaw Praga 39 10. In the footsteps of socialist-realist Warsaw 43 11. What to eat? 46 12. Where to eat? 49 13. Nightlife 53 14. Shopping 55 15. Cultural events 57 16. Practical information 60 1 WARSAW 1, 2, 3... 5 2 3 5 5 1 3 4 3 4 WARSAW IN 1 DAY Here are the top attractions that you can’t miss during a one-day trip to Warsaw! Start with a walk in the centre, see the UNESCO-listed Old Town and the enchanting Royal Łazienki Park, and at the end of the day relax by the Vistula River. -

Architecture: the Museum As Muse Museum Education Program for Grades 6-12

Architecture: The Museum as Muse Museum Education Program for Grades 6-12 Program Outline & Volunteer Resource Package Single Visit Program Option : 2 HOURS Contents of Resource Package Contents Page Program Development & Description 1 Learning Objectives for Students & Preparation Guidelines 2 One Page Program Outline 3 Powerpoint Presentation Overview 4 - 24 Glossary – Architectural Terms 24 - 27 Multimedia Resource Lists (Potential Research Activities) 27 - 31 Field Journal Sample 32 - 34 Glossary – Descriptive Words Program Development This programme was conceived in conjunction with the MOA Renewal project which expanded the Museum galleries, storages and research areas. The excitement that developed during this process of planning for these expanded spaces created a renewed enthusiasm for the architecture of Arthur Erickson and the landscape architecture of Cornelia Oberlander. Over three years the programme was developed with the assistance of teacher specialists, Jane Kinegal, Cambie Secondary School and Russ Timothy Evans, Tupper Secondary School. This programme was developed under the direction of Jill Baird, Curator of Education & Public Programmes, with Danielle Mackenzie, Public Programs & Education Intern 2008/09, Jennifer Robinson, Public Programs & Education Intern 2009/10, Vivienne Tutlewski, Public Programs & Education Intern 2010/2011, Katherine Power, Public Programs & Education Workstudy 2010/11, and Maureen Richardson, Education Volunteer Associate, who were all were key contributors to the research, development and implementation of the programme. Program Description Architecture: The Museum as Muse, Grades 6 - 12 MOA is internationally recognized for its collection of world arts and culture, but it is also famous for its unique architectural setting. This program includes a hands-on phenomenological (sensory) activity, an interior and exterior exploration of the museum, a stunning visual presentation on international museum architecture, and a 30 minute drawing activity where students can begin to design their own museum. -

Museum Air. the Art of Handling Art

lifefeb/2 0 13 magazine Museum air. The art of handling art. contents viewpoint lifefeb/2 0 13 magazine project report Museum buildings. The art of handling art. Page 4 science & technology Art pour l’art. In line with our slogan, we turn to the arts or much more, their place of collection Museum air. Page 10 The art of handling art. or assembly. For in recent decades, very impressive museum buildings have been erected: The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the Tate Modern in London, the feature Acropolis Museum in Athens, the Museum Folkwang in Essen or the very recent The Da Vinci Code. National Museum of China in Beijing. Page 18 Visit with us the world‘s most beautiful, most interesting and most famous museums highlights where we offer insight into the ventilation characteristics of museum buildings. Museums. Page 24 We have also „met“ a fascinating person generally regarded as the universal genius par excellence: Leonardo da Vinci. He is the forefather of fluid dynamics as is evident highlights from his sketchbooks, which were only rediscovered in the 60s of the last century. Museological. Scientists of our time have duplicated, for example, a diving suit and a flying glider from Page 26 his sketches and proven that his technical inventions work. forum & economy And last but not least, read some news about TROX. With the acquisition of the Art at its best economically. TLT building fans, the line of ventilation systems comes full circle for TROX. We can Page 28 now offer our customers the heart of ventilation technology, the fan. -

Museums of Warsaw

Dorota Folga-Januszewska Museums of Warsaw a guide Concept, text, photograph selection and academic editing Dorota Folga-Januszewska Graphics design Tadeusz Nuckowski Photos (page, top/bottom, right/left) Marek Czasnojć 93t; Marta Dziewulska 40t; Grażyna Figura-Laskowska 12b; Dorota Folga-Januszewska 16, 22t, 35, 38t, 57tl, 58, 77b, 78, 86b, 92t; Żaneta Govenlock 73b; Maciej Januszewski 13t; Maciej Miłobędzki 76b; Waldemar Panów, PZ Studio 18–21, 30, 31, 33, 36t, 44, 46, 47br, 48–50, 53, 59, 65, 68, 71, 73t, 74, 81, 82, 87t, 93b; Zbigniew Panów, PZ Studio 8, 10, 12t, 13b, 14b, 22b–26b, 27–29, 32, 34, 36b, 37, 40b, 42t, 43, 45, 51, 52, 54–56, 60–63, 66, 67, 69b, 72, 75, 79, 80, 83–85, 87–92b; Michał Sacharewicz 76t; Jacek Ślubowski 69t; Mariusz Wideryński 38b; Museum’s own collections 9, 11, 14t, 15, 17, 26t, 39, 41, 42b, 47t, bl, 57tr, b, 64, 65, 70, 77t Photos (cover) Waldemar Panów, Zbigniew Panów Text translated by Thomas Crestodina – Atominium Translation Agency Foreword, preface, editors’ note and credits translated by Caryl Swift – Atominium Translation Agency Editors Anna Chudzik Agnieszka Rymarowicz Kinga Urbańska Proofing Anna Crestodina, Elżbieta Grzesiak, Dorota Żurek – Atominium Translation Agency DTP Jakub Kinel Agnieszka Rymarowicz Kinga Urbańska The author, editorial team and publisher extend their warmest thanks to the staff and directors of the museums as well to the students and graduates of the Chair of Con- temporary Art, Theory and Museology at the History of Art Institute and the Museol- ogy Institute of the Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University, Warsaw, for their assistance in verifying the information and gathering the illustrations. -

Open Windows 10

Leticia de Cos Martín Martín Cos de Leticia Beckmann Beckmann Frau than Quappi, much more more much Quappi, pages 47 — 64 47 — 64 pages Clara Marcellán Marcellán Clara in California in California Kandinsky and Klee Klee and Kandinsky of Feininger, Jawlensky, Jawlensky, of Feininger, and the promotion promotion the and Galka Scheyer Galka Scheyer ‘The Blue Four’: Four’: Blue ‘The pages 34 — 46 34 — 46 pages Manzanares Manzanares Juan Ángel Lpez- Ángel Juan ~' of modern art as a collector as a collector Bornemisza’s beginnings beginnings Bornemisza’s - ~~.·;•\ Thyssen Baron On ~ .. ;,~I il~ ' r• , ~.~ ··v,,,:~ ' . -1'\~J"JJj'-': . ·'-. ·•\.·~-~ . 13 — 33 pages Nadine Engel Engel Nadine Expressionist Collection Collection Expressionist Thyssen-Bornemisza’s German German Thyssen-Bornemisza’s Beginning of Hans Heinrich Heinrich Hans of Beginning 1, 1 ~- .,.... Museum Folkwang and the the and Folkwang Museum ,..~I,.. '' i·, '' ·' ' ' .·1,.~.... Resonance Chamber. Chamber. Resonance . ~I•.,Ji'•~-., ~. pages 2 — 12 2 — 12 pages ~ -~~- . ., ,.d' .. Ali. .~ .. December 2020 2020 December 10 10 Open Windows Windows Open Open Windows 10 Resonance Chamber. Museum Folkwang and the Beginning of Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’s German Expressionist Collection Nadine Engel Emil Nolde Young Couple, c. 1931–35 22 HollandischerDirektor bracht ✓ Thyssen-Schatzenach Essen Elnen kaum zu bezifiernden Wert bat elne Ausslellung des Folkwang-Museums, die btszum 20. Marz gezelgt wird: sie ent hiilt hundertzehn Melsterwerke der europaisdlen Malerei des 14. bis 18. Jahrhunderts aus der beriihmten Sammlung Sdtlo8 Roboncz, die heute Im Besitz des nodt Jungen Barons H. H. Thys sen-Bornemisza ist und in der Villa Favorlta bei Lugano ihr r Domlzil hat. Insgesamt mnfafll sie 350 Arbeiten. -

Attraction List

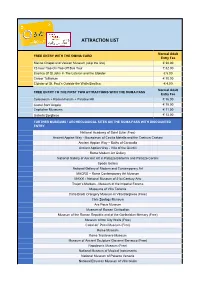

ATTRACTION LIST Normal Adult FREE ENTRY WITH THE OMNIA CARD Entry Fee Sistine Chapel and Vatican Museum (skip the line) € 30.00 72-hour Hop-On Hop-Off Bus Tour € 32.00 Basilica Of St.John In The Lateran and the Cloister € 5.00 Carcer Tullianum € 10.00 Cloister of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls Basilica € 4.00 Normal Adult FREE ENTRY TO THE FIRST TWO ATTRACTIONS WITH THE ROMA PASS Entry Fee Colosseum + Roman Forum + Palatine Hill € 16.00 Castel Sant’Angelo € 15.00 Capitoline Museums € 11.50 Galleria Borghese € 13.00 FURTHER MUSEUMS / ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES ON THE ROMA PASS WITH DISCOUNTED ENTRY National Academy of Saint Luke (Free) Ancient Appian Way - Mausoleum of Cecilia Metella and the Castrum Caetani Ancient Appian Way – Baths of Caracalla Ancient Appian Way - Villa of the Quintili Rome Modern Art Gallery National Gallery of Ancient Art in Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Corsini Spada Gallery National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art MACRO – Rome Contemporary Art Museum MAXXI - National Museum of 21st Century Arts Trajan’s Markets - Museum of the Imperial Forums Museums of Villa Torlonia Carlo Bilotti Orangery Museum in Villa Borghese (Free) Civic Zoology Museum Ara Pacis Museum Museum of Roman Civilization Museum of the Roman Republic and of the Garibaldian Memory (Free) Museum of the City Walls (Free) Casal de’ Pazzi Museum (Free) Rome Museum Rome Trastevere Museum Museum of Ancient Sculpture Giovanni Barracco (Free) Napoleonic Museum (Free) National Museum of Musical Instruments National Museum of Palazzo Venezia National Etruscan -

Travel Guide

TRAVEL GUIDE Traces of the COLD WAR PERIOD The Countries around THE BALTIC SEA Johannes Bach Rasmussen 1 Traces of the Cold War Period: Military Installations and Towns, Prisons, Partisan Bunkers Travel Guide. Traces of the Cold War Period The Countries around the Baltic Sea TemaNord 2010:574 © Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen 2010 ISBN 978-92-893-2121-1 Print: Arco Grafisk A/S, Skive Layout: Eva Ahnoff, Morten Kjærgaard Maps and drawings: Arne Erik Larsen Copies: 1500 Printed on environmentally friendly paper. This publication can be ordered on www.norden.org/order. Other Nordic publications are available at www.norden.org/ publications Printed in Denmark T R 8 Y 1 K 6 S 1- AG NR. 54 The book is produced in cooperation between Øhavsmuseet and The Baltic Initiative and Network. Øhavsmuseet (The Archipelago Museum) Department Langelands Museum Jens Winthers Vej 12, 5900 Rudkøbing, Denmark. Phone: +45 63 51 63 00 E-mail: [email protected] The Baltic Initiative and Network Att. Johannes Bach Rasmussen Møllegade 20, 2200 Copenhagen N, Denmark. Phone: +45 35 36 05 59. Mobile: +45 30 25 05 59 E-mail: [email protected] Top: The Museum of the Barricades of 1991, Riga, Latvia. From the Days of the Barricades in 1991 when people in the newly independent country tried to defend key institutions from attack from Soviet military and security forces. Middle: The Anna Akhmatova Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Handwritten bark book with Akhmatova’s lyrics. Made by a GULAG prisoner, wife of an executed “enemy of the people”. Bottom: The Museum of Genocide Victims, Vilnius, Lithuania.