The Baleful Effect of Computer Languages and Benchmarks Upon Applied Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Organization and Architecture Designing for Performance Ninth Edition

COMPUTER ORGANIZATION AND ARCHITECTURE DESIGNING FOR PERFORMANCE NINTH EDITION William Stallings Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco Upper Saddle River Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montréal Toronto Delhi Mexico City São Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo Editorial Director: Marcia Horton Designer: Bruce Kenselaar Executive Editor: Tracy Dunkelberger Manager, Visual Research: Karen Sanatar Associate Editor: Carole Snyder Manager, Rights and Permissions: Mike Joyce Director of Marketing: Patrice Jones Text Permission Coordinator: Jen Roach Marketing Manager: Yez Alayan Cover Art: Charles Bowman/Robert Harding Marketing Coordinator: Kathryn Ferranti Lead Media Project Manager: Daniel Sandin Marketing Assistant: Emma Snider Full-Service Project Management: Shiny Rajesh/ Director of Production: Vince O’Brien Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Managing Editor: Jeff Holcomb Composition: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Production Project Manager: Kayla Smith-Tarbox Printer/Binder: Edward Brothers Production Editor: Pat Brown Cover Printer: Lehigh-Phoenix Color/Hagerstown Manufacturing Buyer: Pat Brown Text Font: Times Ten-Roman Creative Director: Jayne Conte Credits: Figure 2.14: reprinted with permission from The Computer Language Company, Inc. Figure 17.10: Buyya, Rajkumar, High-Performance Cluster Computing: Architectures and Systems, Vol I, 1st edition, ©1999. Reprinted and Electronically reproduced by permission of Pearson Education, Inc. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Figure 17.11: Reprinted with permission from Ethernet Alliance. Credits and acknowledgments borrowed from other sources and reproduced, with permission, in this textbook appear on the appropriate page within text. Copyright © 2013, 2010, 2006 by Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Prentice Hall. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. -

Id Question Microprocessor Is the Example of ___Architecture. A

Id Question Microprocessor is the example of _______ architecture. A Princeton B Von Neumann C Rockwell D Harvard Answer A Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question _______ bus is unidirectional. A Data B Address C Control D None of these Answer B Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question Use of _______isolates CPU form frequent accesses to main memory. A Local I/O controller B Expansion bus interface C Cache structure D System bus Answer C Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question _______ buffers data transfer between system bus and I/O controllers on expansion bus. A Local I/O controller B Expansion bus interface C Cache structure D None of these Answer B Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question ______ Timing involves a clock line. A Synchronous B Asynchronous C Asymmetric D None of these Answer A Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question -----timing takes advantage of mixture of slow and fast devices, sharing the same bus A Synchronous B asynchronous C Asymmetric D None of these Answer B Marks 1 Unit 1 Id st Question In 1 generation _____language was used to prepare programs. A Machine B Assembly C High level programming D Pseudo code Answer B Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question The transistor was invented at ________ laboratories. A AT &T B AT &Y C AM &T D AT &M Answer A Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question ______is used to control various modules in the system A Control Bus B Data Bus C Address Bus D All of these Answer A Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question The disadvantage of single bus structure over multi bus structure is _____ A Propagation delay B Bottle neck because of bus capacity C Both A and B D Neither A nor B Answer C Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question _____ provide path for moving data among system modules A Control Bus B Data Bus C Address Bus D All of these Answer B Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question Microcontroller is the example of _____ architecture. -

Parallel Computing

Lecture 1: Computer Organization 1 Outline • Overview of parallel computing • Overview of computer organization – Intel 8086 architecture • Implicit parallelism • von Neumann bottleneck • Cache memory – Writing cache-friendly code 2 Why parallel computing • Solving an × linear system Ax=b by using Gaussian elimination takes ≈ flops. 1 • On Core i7 975 @ 4.0 GHz,3 which is capable of about 3 60-70 Gigaflops flops time 1000 3.3×108 0.006 seconds 1000000 3.3×1017 57.9 days 3 What is parallel computing? • Serial computing • Parallel computing https://computing.llnl.gov/tutorials/parallel_comp 4 Milestones in Computer Architecture • Analytic engine (mechanical device), 1833 – Forerunner of modern digital computer, Charles Babbage (1792-1871) at University of Cambridge • Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), 1946 – Presper Eckert and John Mauchly at the University of Pennsylvania – The first, completely electronic, operational, general-purpose analytical calculator. 30 tons, 72 square meters, 200KW. – Read in 120 cards per minute, Addition took 200µs, Division took 6 ms. • IAS machine, 1952 – John von Neumann at Princeton’s Institute of Advanced Studies (IAS) – Program could be represented in digit form in the computer memory, along with data. Arithmetic could be implemented using binary numbers – Most current machines use this design • Transistors was invented at Bell Labs in 1948 by J. Bardeen, W. Brattain and W. Shockley. • PDP-1, 1960, DEC – First minicomputer (transistorized computer) • PDP-8, 1965, DEC – A single bus -

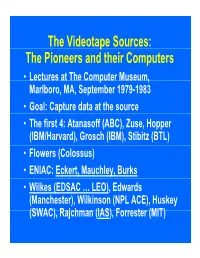

P the Pioneers and Their Computers

The Videotape Sources: The Pioneers and their Computers • Lectures at The Compp,uter Museum, Marlboro, MA, September 1979-1983 • Goal: Capture data at the source • The first 4: Atanasoff (ABC), Zuse, Hopper (IBM/Harvard), Grosch (IBM), Stibitz (BTL) • Flowers (Colossus) • ENIAC: Eckert, Mauchley, Burks • Wilkes (EDSAC … LEO), Edwards (Manchester), Wilkinson (NPL ACE), Huskey (SWAC), Rajchman (IAS), Forrester (MIT) What did it feel like then? • What were th e comput ers? • Why did their inventors build them? • What materials (technology) did they build from? • What were their speed and memory size specs? • How did they work? • How were they used or programmed? • What were they used for? • What did each contribute to future computing? • What were the by-products? and alumni/ae? The “classic” five boxes of a stored ppgrogram dig ital comp uter Memory M Central Input Output Control I O CC Central Arithmetic CA How was programming done before programming languages and O/Ss? • ENIAC was programmed by routing control pulse cables f ormi ng th e “ program count er” • Clippinger and von Neumann made “function codes” for the tables of ENIAC • Kilburn at Manchester ran the first 17 word program • Wilkes, Wheeler, and Gill wrote the first book on programmiidbBbbIiSiing, reprinted by Babbage Institute Series • Parallel versus Serial • Pre-programming languages and operating systems • Big idea: compatibility for program investment – EDSAC was transferred to Leo – The IAS Computers built at Universities Time Line of First Computers Year 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 ••••• BTL ---------o o o o Zuse ----------------o Atanasoff ------------------o IBM ASCC,SSEC ------------o-----------o >CPC ENIAC ?--------------o EDVAC s------------------o UNIVAC I IAS --?s------------o Colossus -------?---?----o Manchester ?--------o ?>Ferranti EDSAC ?-----------o ?>Leo ACE ?--------------o ?>DEUCE Whirl wi nd SEAC & SWAC ENIAC Project Time Line & Descendants IBM 701, Philco S2000, ERA.. -

Parallel Computing

Lecture 1: Single processor performance Why parallel computing • Solving an 푛 × 푛 linear system Ax=b by using Gaussian 1 elimination takes ≈ 푛3 flops. 3 • On Core i7 975 @ 4.0 GHz, which is capable of about 60-70 Gigaflops 푛 flops time 1000 3.3×108 0.006 seconds 1000000 3.3×1017 57.9 days Milestones in Computer Architecture • Analytic engine (mechanical device), 1833 – Forerunner of modern digital computer, Charles Babbage (1792-1871) at University of Cambridge • Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), 1946 – Presper Eckert and John Mauchly at the University of Pennsylvania – The first, completely electronic, operational, general-purpose analytical calculator. 30 tons, 72 square meters, 200KW. – Read in 120 cards per minute, Addition took 200µs, Division took 6 ms. • IAS machine, 1952 – John von Neumann at Princeton’s Institute of Advanced Studies (IAS) – Program could be represented in digit form in the computer memory, along with data. Arithmetic could be implemented using binary numbers – Most current machines use this design • Transistors was invented at Bell Labs in 1948 by J. Bardeen, W. Brattain and W. Shockley. • PDP-1, 1960, DEC – First minicomputer (transistorized computer) • PDP-8, 1965, DEC – A single bus (omnibus) connecting CPU, Memory, Terminal, Paper tape I/O and Other I/O. • 7094, 1962, IBM – Scientific computing machine in early 1960s. • 8080, 1974, Intel – First general-purpose 8-bit computer on a chip • IBM PC, 1981 – Started modern personal computer era Remark: see also http://www.computerhistory.org/timeline/?year=1946 -

Building Computers in 1953: JOHNNIAC"

The Computer Museum History Center presents "Building Computers in 1953: JOHNNIAC" Willis Ware Bill Gunning JOHNNIAC Designer JOHNNIAC Project Engineer Paul Armer Mort Bernstein RAND Department Head JOHNNIAC Software Developer 5:30 PM, Tuesday, Sept. 15, 1998 Computer Museum History Center Building 126 Moffett Field Mt. View JOHNNIAC was one of an illustrious group of computers built in the early 1950's, all inspired by the IAS computer designed by John von Neumann at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Some of these machines were MANIAC (Los Alamos) and ILLIAC (Univ. of Illinois), as well as WEIZAC, AVIDAC, and ORDVAC. JOHNNIAC was built at RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, and named after John von Neumann himself (he "disapproved", but didn't complain too much). This talk will be given in front of JOHNNIAC itself, the actual machine, since it is now part of the Computer Museum History Center at Moffett Field, the world's largest collection of historical computer hardware. JOHNNIAC ran for the first time in March, 1954. It pioneered the development of time shared operating systems with JOSS (the JOHNNIAC Open Shop System). JOSS could support several dozen users with drum swapping -- there were no disk drives then, so no disk swapping, but instead large rotating drums for magnetic storage. JOHNNIAC also inaugurated the commercial use of magnetic core memory, iron doughnuts on wires, which dominated computer memories for the next decade. Among other tasks, JOHNNIAC was also used to develop digitizing tablets for computer input. Our speakers were all working on JOHNNIAC over 40 years ago. -

Computer Architecture ELE 475 / COS 475 Slide Deck 1

Computer Architecture ELE 475 / COS 475 Slide Deck 1: Introduction and Instruction Set Architectures David Wentzlaff Department of Electrical Engineering Princeton University 1 What is Computer Architecture? Application 2 What is Computer Architecture? Application Physics 3 What is Computer Architecture? Application Gap too large to bridge in one step Physics 4 What is Computer Architecture? Application In its broadest definition, Gap too large to computer architecture is the design of the abstraction/ bridge in one step implementation layers that allow us to execute information processing applications efficiently using manufacturing technologies Physics 5 What is Computer Architecture? Application In its broadest definition, Gap too large to computer architecture is the design of the abstraction/ bridge in one step implementation layers that allow us to execute information processing applications efficiently using manufacturing technologies Physics 6 Abstractions in Modern Computing Systems Application Algorithm Programming Language Operating System/Virtual Machines Instruction Set Architecture Microarchitecture Register-Transfer Level Gates Circuits Devices Physics 7 Abstractions in Modern Computing Systems Application Algorithm Programming Language Operating System/Virtual Machines Instruction Set Architecture Computer Architecture Microarchitecture (ELE 475) Register-Transfer Level Gates Circuits Devices Physics 8 Computer Architecture is Constantly Changing Application Application Requirements: Algorithm • Suggest how to improve -

1.12 Historical Perspective and Further Reading 54.E1

1.12 Historical Perspective and Further Reading 54.e1 An active fi eld of science is like an 1.12 Historical Perspective and Further immense anthill; the Reading individual almost vanishes into the mass of minds tumbling over For each chapter in the text, a section devoted to a historical perspective can each other, carrying be found online. We may trace the development of an idea through a series of information from place machines or describe some important projects, and we provide references in case to place, passing it you are interested in probing further. around at the speed of Th e historical perspective for this chapter provides a background for some of the light. key ideas presented therein. Its purpose is to give you the human story behind the Lewis Th omas, “Natural technological advances and to place achievements in their historical context. By Science,” in Th e Lives of learning the past, you may be better able to understand the forces that will shape a Cell , 1974 computing in the future. Each historical perspective section ends with suggestions for additional reading, which are also collected separately in the online section “Further Reading.” The First Electronic Computers J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly at the Moore School of the University of Pennsylvania built what is widely accepted to be the world’s fi rst operational electronic, general-purpose computer. Th is machine, called ENIAC ( Electronic Numerical Integrator and Calculator), was funded by the United States Army and started working during World War II but was not publicly disclosed until 1946. -

Assembly Language

x86 Architectures; Assembly Language Basics of Assembly language for the x86 and x86_64 architectures topics • Preliminary material – a look at what Assembly Language works with - How processors work » A moment of history - Programming model » the registers » the memory The Processor and The System Unit Computer Organization – Programmer's View • Fundamental components: - CPU - Memory - I/O (“everything else”) • Possible connection schemes: - Single Controller (right) - Direct Memory Access (DMA) (below) the Von Neumann Central Processing Unit • a.k.a. CPU or Processor Control - (or microprocessor) Unit • Control unit interprets program instructions Arithmetic • ALU performs numerical Logic and logical operations Unit • Registers access program data Registers • von Neumann model: single connection to memory to/from - the "Von Neumann Bottleneck" memory John von Neumann’s IAS Machine • Built at the Institute for Advanced Studies, Princeton, NJ - 1945 - 1951 • Program instructions and data in single shared memory - ~5 Kilobytes Data Flow 1. Instructions move from memory (through cache) into Control Unit 2. Operands move between memory and data registers 3. Instruction execution causes data movement from/to memory (sometimes) - Computations carry operands from registers (or memory) to ALU, FPU, then back to registers (or memory) - Input/Output operations move values between devices and registers, or between devices and memory locations Modern CPU elements GPU • ALU, FPU, GPU - Do the computations • General-Purpose Data Arithmetic- Registers Registers Logic Units - Hold data for ALU, FPU Floating- • Specialized Registers Point Units - Control Program Flow Specialized Registers • Control Unit - Controls everything Control Unit Memory • Internal busses (a.k.a. - Connect things Store, Storage, • Cache cache or RAM) - Alleviates Von Neumann bottleneck - Generally not visible to programmer Multi-core Processors • Each "core" is a CPU • One chip holds 2, 4, 8, .. -

Appendix M Historical Perspectives and References

M.1 Introduction M-2 M.2 The Early Development of Computers (Chapter 1) M-2 M.3 The Development of Memory Hierarchy and Protection (Chapter 2 and Appendix B) M-9 M.4 The Evolution of Instruction Sets (Appendices A, J, and K) M-17 M.5 The Development of Pipelining and Instruction-Level Parallelism (Chapter 3 and Appendices C and H) M-27 M.6 The Development of SIMD Supercomputers, Vector Computers, Multimedia SIMD Instruction Extensions, and Graphical Processor Units (Chapter 4) M-45 M.7 The History of Multiprocessors and Parallel Processing (Chapter 5 and Appendices F, G, and I) M-55 M.8 The Development of Clusters (Chapter 6) M-74 M.9 Historical Perspectives and References M-79 M.10 The History of Magnetic Storage, RAID, and I/O Buses (Appendix D) M-84 M Historical Perspectives and References If … history … teaches us anything, it is that man in his quest for knowledge and progress is determined and cannot be deterred. John F. Kennedy Address at Rice University (1962) Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. George Santayana The Life of Reason (1905), Vol. 2, Chapter 3 M-2 ■ Appendix M Historical Perspectives and References M.1 Introduction This appendix provides historical background on some of the key ideas presented in the chapters. We may trace the development of an idea through a series of machines or describe significant projects. If you are interested in examining the initial development of an idea or machine or are interested in further reading, references are provided at the end of each section. -

William Stallings Computer Organization and Architecture 8Th Edition

William Stallings Computer Organization and Architecture 8th Edition Chapter 1 Introduction Architecture & Organization 1 • Architecture is those attributes visible to the programmer —Instruction set, number of bits used for data representation, I/O mechanisms, addressing techniques. —e.g. Is there a multiply instruction? • Organization is how features are implemented —Control signals, interfaces, memory technology. —e.g. Is there a hardware multiply unit or is it done by repeated addition? Architecture & Organization 2 • All Intel x86 family share the same basic architecture • The IBM System/370 family share the same basic architecture • This gives code compatibility ... at least backwards • Organization differs within members of the same family, e.g. floating point numerical co- processors with names like 8087, 80287 and 80387. With very few exceptions, the 80486 and subsequent x86 processors then integrated this x87 functionality on chip. Structure & Function • Structure is the way in which components relate to each other • Function is the operation of individual components as part of the structure Function General computer functions: —Data processing —Data storage —Data movement —Control Operations (a) Data movement I/O (peripherals directly attached) Communications/Networking (communication lines) Example application? Operations (a) Data movement I/O (peripherals directly attached) Communications/Networking (communication lines) Camera attached to a PC, sending the frames to a window on the screen of the same PC. Operations (b) Storage Example application? Operations (b) Storage Playing an mp3 file stored in memory to earphones attached to the same PC. Operation (c) Processing from/to storage Example application? Operation (c) Processing from/to storage Any number-crunching application that takes data from memory and stores the result back in memory. -

1.12 Historical Perspective and Further Reading 1.12-3 High and Several Feet Wide

An active fi eld of science is like an immense anthill; the 1.12 Historical Perspective and Further individual almost Reading vanishes into the mass of minds tumbling over each other, carrying For each chapter in the text, a section devoted to a historical perspective can information from place be found online. We may trace the development of an idea through a series of to place, passing it machines or describe some important projects, and we provide references in case around at the speed of you are interested in probing further. light. Th e historical perspective for this chapter provides a background for some of the Lewis Th omas, “Natural key ideas presented therein. Its purpose is to give you the human story behind the Science,” in Th e Lives of technological advances and to place achievements in their historical context. By a Cell , 1974 learning the past, you may be better able to understand the forces that will shape computing in the future. Each historical perspective section ends with suggestions for additional reading, which are also collected separately in the online section “Further Reading.” The First Electronic Computers J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly at the Moore School of the University of Pennsylvania built what is widely accepted to be the world’s fi rst operational electronic, general-purpose computer. Th is machine, called ENIAC ( Electronic Numerical Integrator and Calculator), was funded by the United States Army and started working during World War II but was not publicly disclosed until 1946. ENIAC was a general-purpose machine used for computing artillery-fi ring tables.