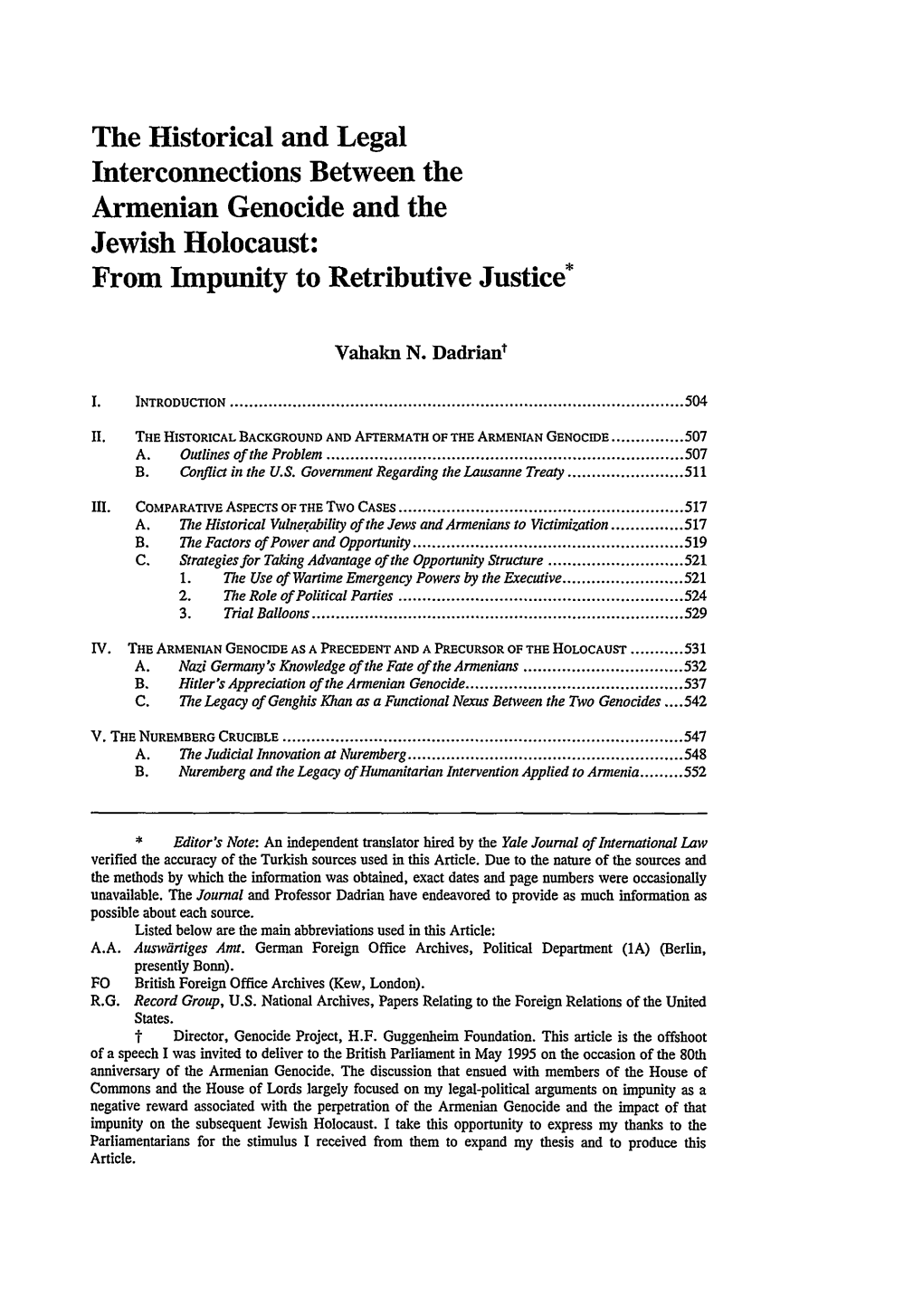

Armenian Genocide and the Jewish Holocaust: from Impunity to Retributive Justice*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5. Between Gleichschaltung and Revolution

Chapter 5 BETWEEN GLEICHSCHALTUNG AND REVOLUTION In the summer of 1935, as part of the Germany-wide “Reich Athletic Com- petition,” citizens in the state of Schleswig-Holstein witnessed the following spectacle: On the fi rst Sunday of August propaganda performances and maneuvers took place in a number of cities. Th ey are supposed to reawaken the old mood of the “time of struggle.” In Kiel, SA men drove through the streets in trucks bearing … inscriptions against the Jews … and the Reaction. One [truck] carried a straw puppet hanging on a gallows, accompanied by a placard with the motto: “Th e gallows for Jews and the Reaction, wherever you hide we’ll soon fi nd you.”607 Other trucks bore slogans such as “Whether black or red, death to all enemies,” and “We are fi ghting against Jewry and Rome.”608 Bizarre tableau were enacted in the streets of towns around Germany. “In Schmiedeberg (in Silesia),” reported informants of the Social Democratic exile organization, the Sopade, “something completely out of the ordinary was presented on Sunday, 18 August.” A no- tice appeared in the town paper a week earlier with the announcement: “Reich competition of the SA. On Sunday at 11 a.m. in front of the Rathaus, Sturm 4 R 48 Schmiedeberg passes judgment on a criminal against the state.” On the appointed day, a large crowd gathered to watch the spectacle. Th e Sopade agent gave the setup: “A Nazi newspaper seller has been attacked by a Marxist mob. In the ensuing melee, the Marxists set up a barricade. -

HBO and the HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, the HISTORICAL FILM, and PUBLIC HISTORY at WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the Facul

HBO AND THE HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, THE HISTORICAL FILM, AND PUBLIC HISTORY AT WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University December 2016 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee __________________________________ Raymond J. Haberski, Ph.D., Chair __________________________________ Thorsten Carstensen, Ph.D. __________________________________ Kevin Cramer, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank the members of my committee for supporting this project and offering indispensable feedback and criticism. I would especially like to thank my chair, Ray Haberski, for being one of the most encouraging advisers I have ever had the pleasure of working with and for sharing his passion for film and history with me. Thorsten Carstensen provided his fantastic editorial skills and for all the times we met for lunch during my last year at IUPUI. I would like to thank Kevin Cramer for awakening my interest in German history and for all of his support throughout my academic career. Furthermore, I would like to thank Jason M. Kelly, Claudia Grossmann, Anita Morgan, Rebecca K. Shrum, Stephanie Rowe, Modupe Labode, Nancy Robertson, and Philip V. Scarpino for all the ways in which they helped me during my graduate career at IUPUI. I also thank the IUPUI Public History Program for admitting a Germanist into the Program and seeing what would happen. I think the experiment paid off. -

Geschichte Des Nationalsozialismus

Ernst Piper Ernst Ernst Piper Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus Von den Anfängen bis heute Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus Band 10264 Ernst Piper Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus Schriftenreihe Band 10291 Ernst Piper Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus Von den Anfängen bis heute Ernst Piper, 1952 in München geboren, lebt heute in Berlin. Er ist apl. Professor für Neuere Geschichte an der Universität Potsdam, Herausgeber mehrerer wissenschaft- licher Reihen und Autor zahlreicher Bücher zur Geschichte des 19. und 20. Jahrhun- derts. Zuletzt erschienen Nacht über Europa. Kulturgeschichte des Ersten Weltkriegs (2014), 1945 – Niederlage und Neubeginn (2015) und Rosa Luxemburg. Ein Leben (2018). Diese Veröffentlichung stellt keine Meinungsäußerung der Bundeszentrale fürpolitische Bildung dar. Für die inhaltlichen Aussagen trägt der Autor die Verantwortung. Wir danken allen Lizenzgebenden für die freundlich erteilte Abdruckgenehmigung. Die In- halte der im Text und im Anhang zitierten Internetlinks unterliegen der Verantwor- tung der jeweiligen Anbietenden; für eventuelle Schäden und Forderungen überneh- men die Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung / bpb sowie der Autor keine Haftung. Bonn 2018 © Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung Adenauerallee 86, 53113 Bonn Projektleitung: Hildegard Bremer, bpb Lektorat: Verena Artz Umschlagfoto: © ullstein bild – Fritz Eschen, Januar 1945: Hausfassade in Berlin-Wilmersdorf Umschlaggestaltung, Satzherstellung und Layout: Naumilkat – Agentur für Kommunikation und Design, Düsseldorf Druck: Druck und Verlagshaus Zarbock GmbH & Co. KG, Frankfurt / Main ISBN: 978-3-7425-0291-9 www.bpb.de Inhalt Einleitung 7 I Anfänge 18 II Kampf 72 III »Volksgemeinschaft« 136 IV Krieg 242 V Schuld 354 VI Erinnerung 422 Anmerkungen 450 Zeittafel 462 Abkürzungen 489 Empfehlungen zur weiteren Lektüre 491 Bildnachweis 495 5 Einleitung Dieses Buch ist eine Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus, keine deutsche Geschichte des 20. -

“Working Towards the Führer” Peter Longerich

“Working Towards the Führer” Ian Kershaw, Hitler. 1889-1936: Hubris; 1936-1945: Nemesis, London: Penguin Books 1998 and 2000, vol. I, xxx + 845 pp., illus., vol. II, xxiii + 1115 pp., illus. Reviewed by Peter Longerich Two years after the publication of the first volume (1998), Ian Kershaw has now brought his mammoth biography of Adolf Hitler to completion. With nearly 2,000 pages, this voluminous work, more than five decades after Hitler’s death, provides us with the first truly comprehensive, rigorously scholarly biography of Hitler. Kershaw, originally trained as a medievalist, pursues an approach akin to the German “structuralist” school and is well acquainted with the bitter debates that raged in the 1970s and 1980s regarding the character of the German dictatorship. His own previous research interests have centered primarily on popular opinion and the image of Hitler in the German population, as well as the historiographic debates on the key questions of the Nazi regime.1 The present book attempts to dovetail biographical and structural interpretative approaches in examining the perennial question of the individual’s power to shape history as exemplified in one of the recent past’s most powerful personalities. His work is also a noteworthy attempt to link German structural history with the British tradition of biography. Kershaw’s methodological point of departure is the Weberian concept of charismatic rule. His interest is thus less in the dictator’s personality and more in the complex of social expectations and motivations projected onto Hitler, which accounted for the “power of the Führer,” his principal concern. Consequently, the author does not blaze some path-breaking new approach; rather, he tries fruitfully to apply one of the familiar interpretations of the Nazi dictatorship to uncommon terrain. -

NARA T733 R10 Guide 97.Pdf

<~ 1985 GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA No. 97 Records of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories (Reichsministerium fiir die besetzten Ostgebiete) and Other Rosenberg Organizations, Part II Microfiche Edition National Archives and Records Administration Washington, DC 1996 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................... i Glossary ......................................................... vi Captured German and Related Records in the National Archives ...................... ix Published Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, VA ................. xxiii Suggestions for Citing Microfilm ....................................... xxvii Instructions for Ordering Microfilm ...................................... xxx Appendix A, Documents from the Rosenberg Collection Incorporated Within the National Archives Collection of World War II War Crimes Records, RG 238 ........... xxxi Appendix B, Original Rosenberg Documents Incorporated Within Records of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), RG 226 .............................. xxxviii Microfiche List .................................................. xxxix INTRODUCTION The Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, VA, constitute a series of finding aids to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) microfilm publications of seized records of German central, regional, and local government agencies and of military commands and units, as well as of the Nazi Party, its component formations, -

A Forgotten Siege the Kutul Amare Victory and the British Soldiers in Yozgat City

Teacher Education and Curriculum Studies 2020; 5(3): 46-52 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/tecs doi: 10.11648/j.tecs.20200503.11 ISSN: 2575-498X (Print); ISSN: 2575-4971 (Online) A Forgotten Siege the Kutul Amare Victory and the British Soldiers in Yozgat City Mehmet Ertug Yavuz The Foreign Languages School, Yozgat Bozok University, Yozgat, Turkey Email address: To cite this article: Mehmet Ertug Yavuz. A Forgotten Siege the Kutul Amare Victory and the British Soldiers in Yozgat City. Teacher Education and Curriculum Studies. Vol. 5, No. 3, 2020, pp. 46-52. doi: 10.11648/j.tecs.20200503.11 Received : June 28, 2019; Accepted : November 6, 2019; Published : June 20, 2020 Abstract: Kutul Amare was the second greatest victory won by the Turks during the First World War after Çanakkale This article tells you about the war from an objective perspective, how and why the war was finally politically won by the British, who was in charge at the time, how did the war progressed and how certain things changed during the time of this war, the imprisoning of the British soldiers in Yozgat City, This is what exactly makes this war so important and interesting. The (weak/ill-so called by the Europeans at those times) Ottoman forces withdrew and reinforced “Selman-i Pak”, under the command of Colonel 'Bearded Nurettin Bey'. While the reinforcement continued, Mirliva-the Major General- Halil Pasha the Uncle of Enver Pasa, entered the frontline with a corps and changed the course of the battle. General Townshend, with 4500 loss regressed to Kutu'l-Amare. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title "Sabiha Gök̨cen's 80-year-old secret" : Kemalist nation formation and the Ottoman Armenians Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2mh3z3k6 Author Ulgen, Fatma Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO ―Sabiha Gökçen‘s 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation Formation and the Ottoman Armenians A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Fatma Ulgen Committee in charge: Professor Robert Horwitz, Chair Professor Ivan Evans Professor Gary Fields Professor Daniel Hallin Professor Hasan Kayalı Copyright Fatma Ulgen, 2010 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Fatma Ulgen is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION For my mother and father, without whom there would be no life, no love, no light, and for Hrant Dink (15 September 1954 - 19 January 2007 iv EPIGRAPH ―In -

Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 39 Number 1 Special Edition: The Nuremberg Laws Article 12 and the Nuremberg Trials Winter 2017 Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer Jonathan Bush Columbia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Recommended Citation Jonathan Bush, Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer, 39 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 259 (2017). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol39/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUSH MACRO FINAL*.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 1/24/17 7:22 PM Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer JONATHAN A. BUSH* Jacob Robinson (1889–1977) was one of the half dozen leading le- gal intellectuals associated with the Nuremberg trials. He was also argu- ably the only scholar-activist who was involved in almost every interna- tional criminal law and human rights battle in the two decades before and after 1945. So there is good reason for a Nuremberg symposium to include a look at his remarkable career in international law and human rights. This essay will attempt to offer that, after a prefatory word about the recent and curious turn in Nuremberg scholarship to biography, in- cluding of Robinson. -

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

Page | 32 Anglisticum Journal (IJLLIS), Volume: 10 | Issue: 6 | June 2021 E-ISSN: 1857-8187 P-ISSN: 1857-8179 Suspended

June 2021 e-ISSN: 1857-8187 p-ISSN: 1857-8179 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5084928 August 2017 e-ISSN: 1857-8187 p-ISSN: 1857-8179 Research Article History THE HUNGARIAN BEER HALL PUTSCH Keywords: radical right-wing organisations, coup d'état, political THE SZEMERE–BOBULA–ULAIN COUP PLAN, 1923 violence, irredentism, anti- Semitism. Balázs Kántás National Archives of Hungary Abstract The years following World War One belonged to a crisis period when political extremities strengthened throughout Europe. In Hungary, it was also the peak of the radical right wing, and some radical political circles even planned coups d’état against the conservative government that was working on the political consolidation of Hungary. A group of radical right-wing politicians led by Member of the Parliament Ferenc Ulain who had been in confidential contact with German radical right-wing movements and politicians (Adolf Hitler and General Erich Ludendorff among them) decided to execute a takeover attempt in 1923, with the help of Bavarian paramilitary movements, harmonizing their plans with the Munich Beer Hall Putsch being in preparation. The present research article makes an attempt to reconstruct this strange chapter of Hungarian political history. Although domestic policy of Hungary was fully determined by British and French interests after the signing of the Peace Treaty of Trianon, secret negotiations with radical right-wing German and Austrian organizations, which went back to 1919, continued for a time in 1921 and 1922 with less intensity than before. The Bethlen Government continued to maintain moderate contacts with German radical right-wing politicians, including former Bavarian Premier and later Commissioner General Gustav von Kahr, General Erich Ludendorff and Adolf Hitler, who was then an emerging and very ambitious young far-right politician in Munich, the centre of the German radical right-wing movements. -

A University of Sussex Phd Thesis Available Online Via Sussex

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details The German colonial settler press in Africa, 1898-1916: a web of identities, spaces and infrastructure. Corinna Schäfer Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex September 2017 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: Summary As the first comprehensive work on the German colonial settler newspapers in Africa between 1898 and 1916, this research project explores the development of the settler press, its networks and infrastructure, its contribution to the construction of identities, as well as to the imagination and creation of colonial space. Special attention is given to the newspapers’ relation to Africans, to other imperial powers, and to the German homeland. The research contributes to the understanding of the history of the colonisers and their societies of origin, as well as to the history of the places and people colonised. -

Das Reich Der Seele Walther Rathenau’S Cultural Pessimism and Prussian Nationalism ~ Dieuwe Jan Beersma

Das Reich der Seele Walther Rathenau’s Cultural Pessimism and Prussian Nationalism ~ Dieuwe Jan Beersma 16 juli 2020 Master Geschiedenis – Duitslandstudies, 11053259 First supervisor: dhr. dr. A.K. (Ansgar) Mohnkern Second supervisor: dhr. dr. H.J. (Hanco) Jürgens Abstract Every year the Rathenau Stiftung awards the Walther Rathenau-Preis to international politicians to spread Rathenau’s ideas of ‘democratic values, international understanding and tolerance’. This incorrect perception of Rathenau as a democrat and a liberal is likely to have originated from the historiography. Many historians have described Rathenau as ‘contradictory’, claiming that there was a clear and problematic distinction between Rathenau’s intellectual theories and ideas and his political and business career. Upon closer inspection, however, this interpretation of Rathenau’s persona seems to be fundamentally incorrect. This thesis reassesses Walther Rathenau’s legacy profoundly by defending the central argument: Walther Rathenau’s life and motivations can first and foremost be explained by his cultural pessimism and Prussian nationalism. The first part of the thesis discusses Rathenau’s intellectual ideas through an in-depth analysis of his intellectual work and the historiography on his work. Motivated by racial theory, Rathenau dreamed of a technocratic utopian German empire led by a carefully selected Prussian elite. He did not believe in the ‘power of a common Europe’, but in the power of a common German Europe. The second part of the thesis explicates how Rathenau’s career is not contradictory to, but actually very consistent with, his cultural pessimism and Prussian nationalism. Firstly, Rathenau saw the First World War as a chance to transform the economy and to make his Volksstaat a reality.