“Working Towards the Führer” Peter Longerich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armenian Genocide and the Jewish Holocaust: from Impunity to Retributive Justice*

The Historical and Legal Interconnections Between the Armenian Genocide and the Jewish Holocaust: From Impunity to Retributive Justice* Vahakn N. Dadrian I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 504 II. THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND AFTERMATH OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE ............... 507 A. Outlines of the Problem .......................................................................... 507 B. Conflict in the U.S. Government Regarding the Lausanne Treaty ........................ 511 M. COMPARATIVE ASPECTS OF THE TwO CASES ........................................................... 517 A. The Historical Vulnerability of the Jews and Armenians to Victimization ............... 517 B. The Factorsof Power and Opportunity........................................................ 519 C. Strategiesfor Taking Advantage of the Opportunity Structure ............................ 521 1. The Use of Wartime Emergency Powers by the Executive ......................... 521 2. The Role of PoliticalParties ........................................................... 524 3. Trial Balloons ............................................................................. 529 IV. THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE AS A PRECEDENT AND A PRECURSOR OF THE HOLOCAUST ........... 531 A. Nazi Germany's Knowledge of the Fate of the Armenians ................................. 532 B. Hitler'sAppreciation of the Armenian Genocide............................................. 537 C. The Legacy of Genghis Kum as a Functional -

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

Catriona Kelly Julian Barnes Antony Beevor Mary Beard Richard J Evans Sameer Rahim Andrew Marr Simon Schama 2 PROSPECT

The past in perspective Catriona Kelly Julian Barnes Antony Beevor Mary Beard Richard J Evans Sameer Rahim Andrew Marr Simon Schama 2 PROSPECT Foreword by Sameer Rahim t Prospect we believe that reflecting on the past glossed over in traditional works. Reviewing Beard’s new book, can provide key insights into the present—and the SPQR, Edith Hall, Professor of Classics at King’s College, Lon- future. In the following pages, you can read a selec- don, hails her “exceptional ability” to keep up with modern tion of some our favourite historical and contem- scholarship as well as her talent for plunging the reader into the porary essays we have published in the last year. thick of the action right from the start. AJulian Barnes’s new novel, The Noise of Time, is based on Nazi propaganda presented Hitler’s Germany as the inher- the life of the Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich. In her itor of the Roman Empire. The man who shaped that image lively and expert review, Catriona Kelly, Professor of Russian at was Josef Goebbels. Richard J Evans, a leading historian of the Oxford University, argues that Barnes has captured the spirit of Nazis, reviews a biography of Goebbels that draws extensively the “technician of survival,” who was in continual fear of having for the first time on his private diaries. What Evans finds is a his music—and his life—being eradicated by Stalin. man, for all his fanatical bombast, who had “a soul devoid of Staying on Russia, Antony Beevor’s column “If I ruled the content.” Also included is my interview with Nikolaus Wachs- world” describes how after the publication of his bestselling Ber- mann, whose acclaimed book KL is the first comprehensive his- lin: the Downfall, which criticised the Red Army’s conduct dur- tory of the Nazi concentration camps. -

The Self-Fulfilled Prophecy: Tracing Convergence in the Development and Conception of the Holocaust

THE SELF-FULFILLED PROPHECY: TRACING CONVERGENCE IN THE DEVELOPMENT AND CONCEPTION OF THE HOLOCAUST A thesis submitted to Anglo-American University for the degree of Bachelor in Humanities, Society and Culture Spring 2020 MILAN SOKOLOVSKI INSTRUCTOR: WILLIAM EDDLESTON SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my independent work. All sources and literature are properly cited and included in the bibliography. I hereby declare that no portion of text in this thesis has been submitted in support of another degree, or qualification thereof, for any other university or institute of learning. I also hereby acknowledge that my thesis will be made publicly available pursuant to Section 47b of Act No. 552/2005 Coll. and AAU’s internal regulations. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, I would like to thank my family, especially my parents, and my partner for putting up with me and my slow, erratic research process. I contributed to ruining a visit that was meant to be filled with family bonding and planned activities and have, at times, been distant. You are all a constant base of support and fulfilment which no sustainable success/development can do without. I love you all so ridiculously much! Second, but no less important with regards to this thesis and my academic development, I would like to thank my instructor, Dr William Eddleston, or “Bill”, as I have been goaded into calling him. Without your classes and criticism (often in the charmingly derisive way that only you know how to do) I would not have achieved what I have in the last year, and the following would probably be 50+ pages of an incredibly abstract, philosophical tangent that would have pained me to finish. -

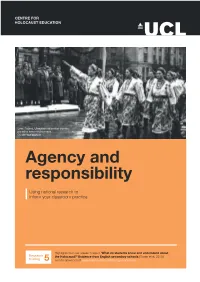

Agency and Responsibility Using National Research to Inform Your Classroom Practice

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION Lvov, Poland, Ukrainian nationalist women parading before Hans Frank. Credit: Yad Vashem Agency and responsibility Using national research to inform your classroom practice. Highlights from our research report ‘What do students know and understand about Research the Holocaust?’ Evidence from English secondary schools (Foster et al, 2016) briefing 5 Free to download at www.holocausteducation.org.uk/research The Holocaust was not inevitable. It happened because of the choices people made and the actions they took as a result of those choices. Understanding the choices and actions of the Why does this matter? people involved is crucial for young people if they are to grasp how the Holocaust was possible, If students only see Hitler and a few leading Nazis as responsible for the as well as being able to critically consider the broader issues of agency and responsibility. Holocaust, then the major challenge of understanding how and why people across Europe became complicit in the murder of their neighbours is overlooked. Our research shows that there are serious gaps in students’ understanding of the extent of collaboration and complicity by both German and non-German citizens across Europe in the persecution and mass This has significant consequence for understanding how and why the Holocaust murder of Jews and other groups. These gaps raise urgent questions about the way the Holocaust happened. Explanations that rest on the actions of a powerful individual and the is taught in our schools and about the importance of sound historical knowledge as a basis for fanatics that surrounded him fail to recognise the extent to which the genocide had understanding the operations of extremism over the intervening decades and in the present day. -

The Holocaust in Court: History, Memory & the Law

UNIVERSITY of GLASGOW The Holocaust in Court: History, Memory & the Law Richard J Evans Professor of Modern History University of Cambridge The Third University of Glasgow Holocaust Memorial Lecture 16 January 2003 © Richard J Evans Note: Professor Evans delivered this lecture unscripted and without notes; the text which follows is a corrected transcript of the tape-recording made of the lecture as it was given at the time. The lecturer wishes to express his thanks to Coleen Doherty of the University of Glasgow for transcribing the text. The Holocaust in Court: History, Memory and the Law Ladies and Gentlemen. I am very grateful for the honour of being asked to give the third in what is already I think a distinguished and important series of lectures. This evening, I am going to talk about my involvement in the sensational Irving/Lipstadt libel trial that happened three years ago in London, to talk about the trial itself, and to offer some general reflections about its significance, particularly in terms of history, the denial of history, history and memory and history and the law. The trial had its origins in a book published by an American academic, Deborah Lipstadt, who teaches at Emory University, in Atlanta, Georgia. The book, called Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory, was published in America in 1993, and identified a thin but more or less continuous stream or rivulet of writing which began shortly after the Second World War and which, the author said, constituted what she called Holocaust denial, a term which Lipstadt did not invent but certainly I think put very much on the map with her book. -

German Historical Institute London Bulletin

German Historical Institute London Bulletin Bd. 25 2003 Nr. 1 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht- kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. IDEAS, CONTEXTS, AND THE PURSUIT OF GENOCIDE by Mark Roseman PETER LONGERICH, The Unwritten Order: Hitlers Role in the Final Solution (Stroud: Tempus Publishing, 2001), 160 pp. ISBN 0 7524 1977 3. £17.00 US $21.99 IRMTRUD WOJAK, Eichmanns Memoiren: Ein kritischer Essay, Wis- senschaftliche Reihe des Fritz Bauer Instituts, Sonderband (Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 2001), 279 pp. ISBN 3 593 36381 X. EUR 25.50 MICHAEL WILDT, Generation des Unbedingten: Das Führungskorps des Reichsicherheitshauptamtes (Hamburg: Hamburger Edition, 2002), 964 pp. ISBN 3 930908 75 1. EUR 35.00 CHRISTIAN GERLACH and GÖTZ ALY, Das letzte Kapitel: Realpoli- tik, Ideologie und der Mord an den ungarischen Juden 1944/45 (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 2002), 481 pp. ISBN 3 421 05505 X. EUR 35.00 For a long time, debate about the Holocausts origins was dominated by the intentionalists and the functionalists. According to the clas- sic intentionalist view, the decision-making process leading to Auschwitz was single-minded and single-handed. Hitler, with a firm grip on power, was hell-bent on murder. -

German Historical Institute London Bulletin

German Historical Institute London Bulletin Bd. 22 2000 Nr. 2 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. PETER LONGERICH, Politik der Vernichtung: Eine Gesamtdarstellung der nationalsozialistischen Judenverfolgung (Munich and Zurich: Piper, 1998), 772 pp. ISBN 3 492 03755 0. DM 78.00 Peter Longerich’s Politik der Vernichtung is the first comprehensive overview of the decision- and policy-making process behind the Nazi persecution of the Jews to be written since the opening of the east European archives. Longerich has also made good use of a wealth of specialized studies that have appeared in recent years. The result is a milestone in Holocaust scholarship that both sums up the current state of research and contributes in important ways to the current debates over interpretation. In the first part of the book, Longerich does not break with the general approach found in the pioneering work (now thirty years old but still impressive) of Karl Schleunes and Uwe Dietrich Adam in outlining the three stages or phases of Nazi persecution in the pre- war period. But Longerich’s synthesis and interpretation adds three important elements. -

Rewriting German History Also by Jan Rüger

Rewriting German History Also by Jan Rüger THE GREAT NAVAL GAME: Britain and Germany in the Age of Empire Also byNikolaus Wachsmann HITLER’S PRISONS: Legal Terror in Nazi Germany KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps Rewriting German History New Perspectives on Modern Germany Editedby Jan Rüger Birkbeck, University of London, UK Nikolaus Wachsmann Birkbeck, University of London, UK Selection and editorial matter © Jan Rüger and Nikolaus Wachsmann 2015 Individual chapters © Respective authors 2015 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issuedbythe Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is theglobal academic imprint of theabove companies andhas companies and representatives throughout the world. -

Heinrich Himmler's Solution to His Homosexual Question: Guiding the Youth to Resist Temptation

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2020 Heinrich Himmler's solution to his homosexual question: Guiding the youth to resist temptation Adam B. Grimm Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Grimm, Adam B., "Heinrich Himmler's solution to his homosexual question: Guiding the youth to resist temptation" (2020). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 18060. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/18060 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Heinrich Himmler’s solution to his homosexual question: Guiding the youth to resist temptation by Adam B. Grimm A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Program of Study Committee: John Monroe, Major Professor Jeremy Best April Eismann The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this thesis. The Graduate College will ensure this thesis is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2020 Copyright © Adam Grimm, 2020. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................. iii CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION AND HISTORIOGRAPHY .................................................... 1 CHAPTER 2. THE YOUNG HIMMLER AND THE WILHELINE DEBATES ON SEXUALITY ............................................................................................................................. -

“Plans from Hell”: Ethical Implications of the Third Reich's Vision for War

“Plans from Hell”: Ethical Implications of the Third Reich’s Vision for War in the East Mark V. Montesclaros In any case, Western norms did not apply on the Eastern Front; the norm there was lawlessness. —Frank Ellis, Barbarossa 1941: Reframing Hitler’s Invasion of Stalin’s Soviet Empire For Hitler, “conventional strategy” was inseparably intertwined with racial ideology. Strategy for Hitler was the grand strategy of race struggle. —Adam Tooze, The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy Let there never come a time when we must cast about and ask how it ever came to this. —Thomas Childers, The Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany Purpose and Scope This paper supports the 2019 Fort Leavenworth Ethics Symposium by examining the ethical implications of prosecuting large-scale combat operations in an historical context. By definition, these operations will almost certainly affect civilians and non-combatants in a complex and ambiguous environment, potentially resulting in not only casualties but also internally displaced persons, refugees or a combination of phenomena. At worst, combat operations, if conducted by nations that have little regard for international norms, can include heinous disregard for human populations, resulting in mass atrocities or even genocide. Such was the case with the subject of this paper—the Third Reich—in its prosecution of the Eastern Front during the Second World War. This paper broadly addresses two themes proposed by the Ethics Symposium announcement and call for papers—the ethical considerations with regard to territory and ownership in large-scale conflict, and when did things start to go wrong ethically in an historic case of genocide—in this case the Nazi extermination of European Jewry. -

Heinrich Himmler: a Life'

H-Genocide McMillan on Longerich, 'Heinrich Himmler: A Life' Review published on Monday, December 2, 2013 Peter Longerich. Heinrich Himmler: A Life. Trans. Jeremy Noakes and Leslie Sharpe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. xviii + 1,031 pp. $34.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-19-959232-6. Reviewed by Dan McMillan Published on H-Genocide (December, 2013) Commissioned by Elisa G. von Joeden-Forgey In a noted 1991 essay, leading Holocaust historian Saul Friedländer used Heinrich Himmler as an example to support his contention that the Holocaust, unlike other historical events, “could well be inaccessible to all attempts at a significant representation and interpretation.” Analyzing Himmler’s notorious Posen speech of October 4, 1943, Friedländer highlights Himmler’s statement that the SS must keep the murder of the Jewish people secret for all time, when he called it “a glorious page in our history and one that has never been written and can never be written.”[1] From this statement Friedländer concludes that Himmler and his accomplices did not really believe the racial theories that supposedly justified their actions. Consequently, the Holocaust did not represent an “‘inversion of all values,’” but rather “an amorality beyond all categories of evil. Human beings are no longer reduced to instruments; they lose their humanity entirely.” Having lost their humanity, the perpetrators are therefore no longer accessible to the empathy that remains the heart of the historian’s method. As Friedländer trenchantly formulates his claim, “no one of sound mind would wish to interpret the events from Hitler’s viewpoint.”[2] But do historians have to become Adolf Hitler or Heinrich Himmler to understand why these men acted as they did? Concerning Himmler, at least, Peter Longerich handily demonstrates that we can achieve an understanding of the man and his actions that is nuanced and thorough, if necessarily imperfect.