Hitler's American Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D'antonio, Michael Senior Thesis.Pdf

Before the Storm German Big Business and the Rise of the NSDAP by Michael D’Antonio A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Degree in History with Distinction Spring 2016 © 2016 Michael D’Antonio All Rights Reserved Before the Storm German Big Business and the Rise of the NSDAP by Michael D’Antonio Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. James Brophy Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. David Shearer Committee member from the Department of History Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. Barbara Settles Committee member from the Board of Senior Thesis Readers Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Michael Arnold, Ph.D. Director, University Honors Program ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This senior thesis would not have been possible without the assistance of Dr. James Brophy of the University of Delaware history department. His guidance in research, focused critique, and continued encouragement were instrumental in the project’s formation and completion. The University of Delaware Office of Undergraduate Research also deserves a special thanks, for its continued support of both this work and the work of countless other students. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

Document and Analyse: the Legacy of Klemperer, Fraenkel and Neumann for Contemporary Human Rights Engagement Luz Oette, School O

This is the version of the article accepted for publication in Human Rights Quarterly published by John Hopkins University Press: https://www.press.jhu.edu/journals/human_rights_quarterly/index.html Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/23313/ Document and analyse: The legacy of Klemperer, Fraenkel and Neumann for contemporary human rights engagement Luz Oette, School of Law, SOAS University of London Human rights discourse has been criticised for being legalistic, decontextualised and failing to focus on factors explaining violations. Victor Klemperer‟s diaries chronicled the life and suffering of a German Jew in Nazi Germany and the manipulation of language by a totalitarian regime. Ernst Fraenkel‟s Dual State and Franz Neumann‟s Behemoth set out theories offering profound insights into the legal and political nature of the Nazi system. Revisiting their work from a human rights perspective is richly rewarding, providing examples of engaged scholarship that combined documentation and critical analysis. Their writings hold important lessons for contemporary human rights engagement and its critics. I. Introduction The human rights movement and language of human rights has been the subject of sustained criticism. Besides its supposed Western liberal bias, critics have focused particularly on human rights as a mode of political engagement. Human rights discourse is seen as legalistic and decontextualised. Richard Wilson argued in 1997 that human rights reports “can depoliticise human rights violations -

J'une 28, 1933. on This 28Th Day Or June 1933~ the Board· Ot TI

J'une 28, 1933. On this 28th day or June 1933~ the Board· ot TI'U8tees ot the ArkansE State Teachers College met in the President's otti ce at Conway, Arkansas at 11 a.m• with the tbllowing members present and voting: Hirst, Leonard; Humphreys, Compere~ A.ndrews, Fre,uenthe.l ,!Uld: Smith Minutes or the l ast meeting were r ead and approved. Motion by Andrews, seocaded by Smith (l) that Miss Jessie Montgomer be employed as s Upe rvisor tor 1218 jun1 or h igb school in the Training School tor t~ months or July and August at a salaey or $114.90 a month; (2) that Kiss Waldron be assigned in t h9 epi:ropriation budget as auistant int~ DepartmEll.t or Social SoiE11.ce 111.th no change in salary; .(3) that Jerry Dalrymple, Athletic Coach, b.e assigned as adcUtiona.l assistant instead ot an assistant in Social Seienoe, at a salary of ~200.00 a month beginning September l; (4) that the salaries ot Miss Lucy Torson and Miss Edith Langley be made il950 each tor the next year in order to contorm to t he approprta t:l.on bulget; (5) that the resolution passed April 15, 1933 asking the Governor to readjust the amounts appropriated tor salaries in Ite~ 29 and 30 tor 1933-34 be rescinded Motion carrt ed • .llotion by Andrews~ seconded by HumJi>,reys that Guy E. Smith, Disbursing Age~, be instructed to pay tor the grading or oorrespondence papers at the rate ot t l.50 tor each term hours credit; that said payment be paid frcm the Extension Fund upon the eompletion ot each correspondence course; tb:i.t the pa}'JD3nt for tuch work made to meui>ers of tbe regular tacuUy be in addition to salaries tor t.each1ng~ provided that no member or the faculty will be paid more than $450.00 par annum in addi tio:n to the regutar salary. -

Discrimination and Law in Nazi Germany

Cohen Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies Name:_______________________________ at Keene State College __________________________________________________________________________________________________ “To Remember…and to Teach.” www.keene.edu/cchgs Student Outline: Destroying Democracy From Within (1933-1938) 1. In the November 1932 elections the Nazis received _______ (%) of the vote. 2. Hitler was named Chancellor of a right-wing coalition government on _________________ _____, __________. 3. Hitler’s greatest fear is that he could be dismissed by President ____________________________. 4. Hitler’s greatest unifier of the many conservatives was fear of the _____________. 5. The Reichstag Fire Decree of February 1933 allowed Hitler to use article _______ to suspend the Reichstag and suspend ________________ ____________ for all Germans. 6. In March 5, 1933 election, the Nazi Party had _________ % of the vote. 7. Concentration camps (KL) emerged from below as camps for “__________________ ________________” prisoners. 8. On March 24, 1933, the _______________ Act gave Hitler power to rule as dictator during the declared “state of emergency.” It was the __________________ Center Party that swayed the vote in Hitler’s favor. 9. Franz Schlegelberger became the State Secretary in the German Ministry of ___________________. He believed that the courts role was to maintain ________________ __________________. He based his rulings on the principle of the ____________________ ___________________ order. He endorsed the Enabling Act because the government, in his view, could act with _______________, ________________, and _____________________. 10. One week after the failed April 1, 1933 Boycott, the Nazis passed the “Law for the Restoration of the Professional _________________ ______________________. The April 11 supplement attempted to legally define “non-Aryan” as someone with a non-Aryan ____________________ or ________________________. -

America Holocaust 0.Pdf

Facing History and Ourselves A Guide to THE AMERICAN EXPERIENCE Documentary America and the Holocaust: Deceit and Indifference Facing History and Ourselves would like to acknowledge Phyllis Goldstein who wrote the manuscript in collaboration with the Facing History team under the direction of Margot Stern Strom and Marc Skvirsky; the design efforts of Joe Wiellette and the thoughtful reviews of David S. Wyman and Martin Ostrow. This study guide was produced by Facing History and Ourselves in consultation with the Educational Print and Outreach Department of the WGBH Educational Foundation. Major funding was provided by the Rita J. and Stanley H. Kaplan Foundation. Additional funding provided by The Jaffe Foundation, A. C. Ratshesky Foundation, Mr. M. Howard Jacobson, Mr. and Mrs. William J. Poorvu, Arnold and Anne Hiatt, David and Muriel Pokross, Dr. and Mrs. Maurice Vanderpol, Ms. Joyce Friedman, Mr. Milton L. Gail, Edward and Leona Zarsky, Dr. and Mrs. David Kaufman, Mr. Richard Arisian, Dr. and Mrs. Alan N. Ertel, Dr. and Mrs. Jonathan Cohen, Dr. and Mrs. Albert Schilling, Ms. Harriet Reisen, Julius and Ruth Kaplan, Samuel and Sidonia Natansohn, Ms. Anna Kolodner, Lorraine Betwenik Gotlib and Sanford Gotlib, and Mr. Joseph M. Rainho. America and the Holocaust: Deceit and Indifference is a Fine Cut Productions, Inc. film for THE AMERICAN EXPERIENCE, a production of WGBH Boston. Writer, Producer, and Director: Martin Ostrow Executive Producer: Judith Crichton Senior Producer: Margaret Drain America and the Holocaust: Deceit and Indifference is the winner of a Golden Eagle Award from CINE (Council on Nontheatrical Events), a Gold Plaque Award at the Chicago International Film Festival, and an award from the Writer’s Guild of America. -

Eastern Europe

NAZI PLANS for EASTE RN EUR OPE A Study of Lebensraum Policies SECRET NAZI PLANS for EASTERN EUROPE A Study of Lebensraum Policies hy Ihor Kamenetsky ---- BOOKMAN ASSOCIATES :: New York Copyright © 1961 by Ihor Kamenetsky Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 61-9850 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY UNITED PRINTING SERVICES, INC. NEW HAVEN, CONN. TO MY PARENTS Preface The dawn of the twentieth century witnessed the climax of imperialistic competition in Europe among the Great Pow ers. Entrenched in two opposing camps, they glared at each other over mountainous stockpiles of weapons gathered in feverish armament races. In the one camp was situated the Triple Entente, in the other the Triple Alliance of the Central Powers under Germany's leadership. The final and tragic re sult of this rivalry was World War I, during which Germany attempted to realize her imperialistic conception of M itteleuropa with the Berlin-Baghdad-Basra railway project to the Near East. Thus there would have been established a transcontinental highway for German industrial and commercial expansion through the Persian Gull to the Asian market. The security of this highway required that the pressure of Russian imperi alism on the Middle East be eliminated by the fragmentation of the Russian colonial empire into its ethnic components. Germany· planned the formation of a belt of buffer states ( asso ciated with the Central Powers and Turkey) from Finland, Beloruthenia ( Belorussia), Lithuania, Poland to Ukraine, the Caucasus, and even to Turkestan. The outbreak and nature of the Russian Revolution in 1917 offered an opportunity for Imperial Germany to realize this plan. -

Nazi Privatization in 1930S Germany1 by GERMÀ BEL

Economic History Review (2009) Against the mainstream: Nazi privatization in 1930s Germany1 By GERMÀ BEL Nationalization was particularly important in the early 1930s in Germany.The state took over a large industrial concern, large commercial banks, and other minor firms. In the mid-1930s, the Nazi regime transferred public ownership to the private sector. In doing so, they went against the mainstream trends in western capitalistic countries, none of which systematically reprivatized firms during the 1930s. Privatization was used as a political tool to enhance support for the government and for the Nazi Party. In addition, growing financial restrictions because of the cost of the rearmament programme provided additional motivations for privatization. rivatization of large parts of the public sector was one of the defining policies Pof the last quarter of the twentieth century. Most scholars have understood privatization as the transfer of government-owned firms and assets to the private sector,2 as well as the delegation to the private sector of the delivery of services previously delivered by the public sector.3 Other scholars have adopted a much broader meaning of privatization, including (besides transfer of public assets and delegation of public services) deregulation, as well as the private funding of services previously delivered without charging the users.4 In any case, modern privatization has been usually accompanied by the removal of state direction and a reliance on the free market. Thus, privatization and market liberalization have usually gone together. Privatizations in Chile and the UK, which began to be implemented in the 1970s and 1980s, are usually considered the first privatization policies in modern history.5 A few researchers have found earlier instances. -

Presentation Slides

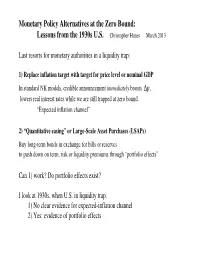

Monetary Policy Alternatives at the Zero Bound: Lessons from the 1930s U.S. Christopher Hanes March 2013 Last resorts for monetary authorities in a liquidity trap: 1) Replace inflation target with target for price level or nominal GDP In standard NK models, credible announcement immediately boosts ∆p, lowers real interest rates while we are still trapped at zero bound. “Expected inflation channel” 2) “Quantitative easing” or Large-Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs) Buy long-term bonds in exchange for bills or reserves to push down on term, risk or liquidity premiums through “portfolio effects” Can 1) work? Do portfolio effects exist? I look at 1930s, when U.S. in liquidity trap. 1) No clear evidence for expected-inflation channel 2) Yes: evidence of portfolio effects Expected-inflation channel: theory Lessons from the 1930s U.S. β New-Keynesian Phillips curve: ∆p ' E ∆p % (y&y n) t t t%1 γ t T β a distant horizon T ∆p ' E [∆p % (y&y n) ] t t t%T λ j t%τ τ'0 n To hit price-level or $AD target, authorities must boost future (y&y )t%τ For any given path of y in near future, while we are still in liquidity trap, that raises current ∆pt , reduces rt , raises yt , lifts us out of trap Why it might fail: - expectations not so forward-looking, rational - promise not credible Svensson’s “Foolproof Way” out of liquidity trap: peg to depreciated exchange rate “a conspicuous commitment to a higher price level in the future” Expected-inflation channel: 1930s experience Lessons from the 1930s U.S. -

![Autarky and Lebensraum. the Political Agenda of Academic Plant Breeding in Nazi Germany[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9515/autarky-and-lebensraum-the-political-agenda-of-academic-plant-breeding-in-nazi-germany-1-289515.webp)

Autarky and Lebensraum. the Political Agenda of Academic Plant Breeding in Nazi Germany[1]

Journal of History of Science and Technology | Vol.3 | Fall 2009 Autarky and Lebensraum. The political agenda of academic plant breeding in Nazi Germany[1] By Thomas Wieland * Introduction In a 1937 booklet entitled Die politischen Aufgaben der deutschen Pflanzenzüchtung (The Political Objectives of German Plant Breeding), academic plant breeder and director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (hereafter KWI) for Breeding Research in Müncheberg near Berlin Wilhelm Rudorf declared: “The task is to breed new crop varieties which guarantee the supply of food and the most important raw materials, fibers, oil, cellulose and so forth from German soils and within German climate regions. Moreover, plant breeding has the particular task of creating and improving crops that allow for a denser population of the whole Nordostraum and Ostraum [i.e., northeastern and eastern territories] as well as other border regions…”[2] This quote illustrates two important elements of National Socialist ideology: the concept of agricultural autarky and the concept of Lebensraum. The quest for agricultural autarky was a response to the hunger catastrophe of World War I that painfully demonstrated Germany’s dependence on agricultural imports and was considered to have significantly contributed to the German defeat in 1918. As Herbert Backe (1896–1947), who became state secretary in 1933 and shortly after de facto head of the German Ministry for Food and Agriculture, put it: “World War 1914–18 was not lost at the front-line but at home because the foodstuff industry of the Second Reich [i.e., the German Empire] had failed.”[3] The Nazi regime accordingly wanted to make sure that such a catastrophe would not reoccur in a next war. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Racial State” by Scholars

Obsession, Separation, and Extermination: The Nazi Reordering of Germany 2. Nazi Germany is described as a “Racial State” by scholars. Explain the place of racism and in particular of anti-Semitism to the Nazi reordering of Germany and of Europe. In your analysis pay attention to both ideology and practice, to domestic and foreign policy, to culture and to politics. Following the Nazi rise to power, officials declared that “hereafter the Reich will recognize only three classes: Germans (of German or related blood), Jews and ‘Jewish mixtures’” (Birchall, “Reich Puts Laws on Jews in Force; Trade Untouched”, in Moeller, 98). This quote lies in a source written in 1935, well before the mass extermination of the Jewish population began in the Third Reich. The politics of the Reich were built around a feeling of Volk and racial similarities; those who were declared to be outside of the Volk were ostracized by the practice of laws within the German culture. Racist ideology was formed and manifested quickly upon the rise of Nazi power, with racial laws causing an obsession with heritage and the split of Germans and Jews. Nazi racism spread internationally as well, particularly as the Nazis began the occupation of Poland, Austria, and other nations. This potent racism, especially toward Jews, fueled the manner in which the Nazis reordered the German nation into a race-obsessed state and spread their obsession into neighboring countries. Politics were the origin of the extreme anti-Semitism in Nazi German. The politicians decided what the German people should believe and advertised it well enough to succeed in changing the outlook of the population.