“Plans from Hell”: Ethical Implications of the Third Reich's Vision for War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armenian Genocide and the Jewish Holocaust: from Impunity to Retributive Justice*

The Historical and Legal Interconnections Between the Armenian Genocide and the Jewish Holocaust: From Impunity to Retributive Justice* Vahakn N. Dadrian I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 504 II. THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND AFTERMATH OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE ............... 507 A. Outlines of the Problem .......................................................................... 507 B. Conflict in the U.S. Government Regarding the Lausanne Treaty ........................ 511 M. COMPARATIVE ASPECTS OF THE TwO CASES ........................................................... 517 A. The Historical Vulnerability of the Jews and Armenians to Victimization ............... 517 B. The Factorsof Power and Opportunity........................................................ 519 C. Strategiesfor Taking Advantage of the Opportunity Structure ............................ 521 1. The Use of Wartime Emergency Powers by the Executive ......................... 521 2. The Role of PoliticalParties ........................................................... 524 3. Trial Balloons ............................................................................. 529 IV. THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE AS A PRECEDENT AND A PRECURSOR OF THE HOLOCAUST ........... 531 A. Nazi Germany's Knowledge of the Fate of the Armenians ................................. 532 B. Hitler'sAppreciation of the Armenian Genocide............................................. 537 C. The Legacy of Genghis Kum as a Functional -

PURL: G S Lili II a R Y OP EVENTS

No. XXVII. April 21st 1947. UNITED NATIONS WAR CRIMES (VM/TSSICN. (Research Office). W A R CRIMES O V 3 DIGEST. ¿"NOTBî The above title replaces that of Press News Sunmary used in the early numbers of this eries. For internal circulation to the Commission.^ CONTENTS. SUMMARY OP EVENTS. Page. EUROPE. 1. PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/0556af/ G S lili II A R Y OP EVENTS. 5UH0PE. A U S T R I A. Investigations into suspected cases of war ori^«?. Lina radio reported (1 0 ,4«47) that under the jurisdiction of the five People's Courts in Upper Austria and Salzburg - the region of the Linz Chief Public Rrosecutor' s Office - 5,157 preliminary investigations were being nado into cases of suspected war crine3 and underground nenborshi^ of the Nazi party. About 500 trials wore begun la3t year; 342 being ccncludod, two with death sent ences and ll6 with acquittals. Arrests. 7icner Zeitung reported (1,4*47) that the Innsbruck police had arrested the former SS Ob ers turn führer Richard. KORNHERR. CZECHOSLOVAKIA. The Tiso Trial, (see Ho, XXVI, p.2 of this Digest) The Daily Telegraph reported free Prague (16,4.47) that Josef TISO, former President of Slovakia during the German occupation, had been sentenced by the People's Court in Bratislava to death by hanging, Ferdinand DURCANSKY, his former Foreign Kinister, received a similar sentence. During his trial TISO admitted giving military aid to the Germans but denied signing a declaration of \ war on Britain and the United States, Sentence on a Gestapo Official, An Agency message reported frcm Berlin (7 .2 ,4 7 ) that Karel DUCHGN, described, as the most cruel Gestapo man in Olcmouc, had been sentenced to death by the Olccnouc People's Court, He took part in the killing of 21 people in a May 1945 rising and persecuted Slovak partisans. -

Introduction to the Captured German Records at the National Archives

THE KNOW YOUR RECORDS PROGRAM consists of free events with up-to-date information about our holdings. Events offer opportunities for you to learn about the National Archives’ records through ongoing lectures, monthly genealogy programs, and the annual genealogy fair. Additional resources include online reference reports for genealogical research, and the newsletter Researcher News. www.archives.gov/calendar/know-your-records The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is the nation's record keeper. Of all the documents and materials created in the course of business conducted by the United States Federal government, only 1%–3% are determined permanently valuable. Those valuable records are preserved and are available to you, whether you want to see if they contain clues about your family’s history, need to prove a veteran’s military service, or are researching an historical topic that interests you. www.archives.gov/calendar/know-your-records December 14, 2016 Rachael Salyer Rachael Salyer, archivist, discusses records from Record Group 242, the National Archives Collection of Foreign Records Seized, and offers strategies for starting your historical or genealogical research using the Captured German Records. www.archives.gov/calendar/know-your-records Rachael is currently an archivist in the Textual Processing unit at the National Archives in College Park, MD. In addition, she assists the Reference unit respond to inquiries about World War II and Captured German records. Her career with us started in the Textual Research Room. Before coming to the National Archives, Rachael worked primarily as a professor of German at Clark University in Worcester, MA and a professor of English at American International College in Springfield, MA. -

“Working Towards the Führer” Peter Longerich

“Working Towards the Führer” Ian Kershaw, Hitler. 1889-1936: Hubris; 1936-1945: Nemesis, London: Penguin Books 1998 and 2000, vol. I, xxx + 845 pp., illus., vol. II, xxiii + 1115 pp., illus. Reviewed by Peter Longerich Two years after the publication of the first volume (1998), Ian Kershaw has now brought his mammoth biography of Adolf Hitler to completion. With nearly 2,000 pages, this voluminous work, more than five decades after Hitler’s death, provides us with the first truly comprehensive, rigorously scholarly biography of Hitler. Kershaw, originally trained as a medievalist, pursues an approach akin to the German “structuralist” school and is well acquainted with the bitter debates that raged in the 1970s and 1980s regarding the character of the German dictatorship. His own previous research interests have centered primarily on popular opinion and the image of Hitler in the German population, as well as the historiographic debates on the key questions of the Nazi regime.1 The present book attempts to dovetail biographical and structural interpretative approaches in examining the perennial question of the individual’s power to shape history as exemplified in one of the recent past’s most powerful personalities. His work is also a noteworthy attempt to link German structural history with the British tradition of biography. Kershaw’s methodological point of departure is the Weberian concept of charismatic rule. His interest is thus less in the dictator’s personality and more in the complex of social expectations and motivations projected onto Hitler, which accounted for the “power of the Führer,” his principal concern. Consequently, the author does not blaze some path-breaking new approach; rather, he tries fruitfully to apply one of the familiar interpretations of the Nazi dictatorship to uncommon terrain. -

SS-Totenkopfverbände from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande)

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history SS-Totenkopfverbände From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande) Navigation Not to be confused with 3rd SS Division Totenkopf, the Waffen-SS fighting unit. Main page This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. No cleanup reason Contents has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2010) Featured content Current events This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding Random article citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2010) Donate to Wikipedia [2] SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), rendered in English as "Death's-Head Units" (literally SS-TV meaning "Skull Units"), was the SS organization responsible for administering the Nazi SS-Totenkopfverbände Interaction concentration camps for the Third Reich. Help The SS-TV was an independent unit within the SS with its own ranks and command About Wikipedia structure. It ran the camps throughout Germany, such as Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Community portal Buchenwald; in Nazi-occupied Europe, it ran Auschwitz in German occupied Poland and Recent changes Mauthausen in Austria as well as numerous other concentration and death camps. The Contact Wikipedia death camps' primary function was genocide and included Treblinka, Bełżec extermination camp and Sobibor. It was responsible for facilitating what was called the Final Solution, Totenkopf (Death's head) collar insignia, 13th Standarte known since as the Holocaust, in collaboration with the Reich Main Security Office[3] and the Toolbox of the SS-Totenkopfverbände SS Economic and Administrative Main Office or WVHA. -

![Autarky and Lebensraum. the Political Agenda of Academic Plant Breeding in Nazi Germany[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9515/autarky-and-lebensraum-the-political-agenda-of-academic-plant-breeding-in-nazi-germany-1-289515.webp)

Autarky and Lebensraum. the Political Agenda of Academic Plant Breeding in Nazi Germany[1]

Journal of History of Science and Technology | Vol.3 | Fall 2009 Autarky and Lebensraum. The political agenda of academic plant breeding in Nazi Germany[1] By Thomas Wieland * Introduction In a 1937 booklet entitled Die politischen Aufgaben der deutschen Pflanzenzüchtung (The Political Objectives of German Plant Breeding), academic plant breeder and director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (hereafter KWI) for Breeding Research in Müncheberg near Berlin Wilhelm Rudorf declared: “The task is to breed new crop varieties which guarantee the supply of food and the most important raw materials, fibers, oil, cellulose and so forth from German soils and within German climate regions. Moreover, plant breeding has the particular task of creating and improving crops that allow for a denser population of the whole Nordostraum and Ostraum [i.e., northeastern and eastern territories] as well as other border regions…”[2] This quote illustrates two important elements of National Socialist ideology: the concept of agricultural autarky and the concept of Lebensraum. The quest for agricultural autarky was a response to the hunger catastrophe of World War I that painfully demonstrated Germany’s dependence on agricultural imports and was considered to have significantly contributed to the German defeat in 1918. As Herbert Backe (1896–1947), who became state secretary in 1933 and shortly after de facto head of the German Ministry for Food and Agriculture, put it: “World War 1914–18 was not lost at the front-line but at home because the foodstuff industry of the Second Reich [i.e., the German Empire] had failed.”[3] The Nazi regime accordingly wanted to make sure that such a catastrophe would not reoccur in a next war. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

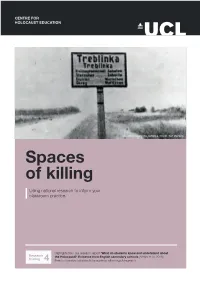

Spaces of Killing Using National Research to Inform Your Classroom Practice

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION The entrance sign to Treblinka. Credit: Yad Vashem Spaces of killing Using national research to inform your classroom practice. Highlights from our research report ‘What do students know and understand about Research the Holocaust?’ Evidence from English secondary schools (Foster et al, 2016) briefing 4 Free to download at www.holocausteducation.org.uk/research If students are to understand the significance of the Holocaust and the full enormity of its scope and scale, they need to appreciate that it was a continent-wide genocide. Why does this matter? The perpetrators ultimately sought to kill every Jew, everywhere they could reach them with victims Knowledge of the ‘spaces of killing’ is crucial to an understanding of the uprooted from communities across Europe. It is therefore crucial to know about the geography of the Holocaust. If students do not appreciate the scale of the killings outside of Holocaust relating to the development of the concentration camp system; the location, role and purpose Germany and particularly the East, then it is impossible to grasp the devastation of the ghettos; where and when Nazi killing squads committed mass shootings; and the evolution of the of Jewish communities in Europe or the destruction of diverse and vibrant death camps. cultures that had developed over centuries. This briefing, the fourth in our series, explores students’ knowledge and understanding of these key Entire communities lost issues, drawing on survey research and focus group interviews with more than 8,000 11 to 18 year olds. Thousands of small towns and villages in Poland, Ukraine, Crimea, the Baltic states and Russia, which had a majority Jewish population before the war, are now home to not a single Jewish person. -

THE NAZI ANTI-URBAN UTOPIA Generalplan Ost

MONOGRAPH Mètode Science Studies Journal, 10 (2020): 165-171. University of Valencia. DOI: 10.7203/metode.10.13009 ISSN: 2174-3487. eISSN: 2174-9221. Submitted: 03/09/2018. Approved: 11/03/2019. THE NAZI ANTI-URBAN UTOPIA Generalplan Ost UNAI FERNÁNDEZ DE BETOÑO Nazi Germany saw Eastern Europe as an opportunity to expand its territory, its living space. Poland would become the laboratory for an inhumane colonisation plan, the Generalplan Ost (“General Plan for the East”), which involved replacement of the non-Aryan population with Germanic farmers. The anti-urban management of that lobotomised territory was scientifically drafted by a group of architects, geographers, and agronomists working under the orders of Heinrich Himmler. The urban planning aspects of this utopian plan, based on central place theory, self-sufficiency, and neighbourhood units, were of great technical interest and influenced the creation of new communities within Franco’s regime. However, we cannot overlook the fact that, had the Nazi plan been completed, it would have resulted in the forced relocation of 31 million Europeans. Keywords: Nazi Germany, Generalplan Ost, land management, colonisation, urban planning. ■ INTRODUCTION for the colonisation of the Eastern territories, mainly the land occupied in Poland between 1939 and 1945. The fields of urban planning and land management The Nazi colonisation of Poland, both in territories have historically focused on significantly different annexed by the Third Reich and those in the objectives depending on the authors of each plan and Generalgouvernement, was a testing ground for land when they were created. Some have given greater management and was understood as a scientific and prominence to the artistic components of urban technical discipline. -

The Reasons Why Germany Invaded Russia in 1941

THE REASONS WHY GERMANY INVADED RUSSIA IN 1941 Operation Barbarossa (German: Unternehmen Barbarossa) was the code name for the Axis In the two years leading up to the invasion, Germany and the Soviet Union signed political and economic pacts for strategic purposes. .. The reasons for the postponement of Barbarossa from the initially planned date of 15 May to. Gerd von Rundstedt , with an armoured group under Gen. On 25 November , the Soviet Union offered a written counter-proposal to join the Axis if Germany would agree to refrain from interference in the Soviet Union's sphere of influence, but Germany did not respond. The Hunger Plan outlined how the entire urban population of conquered territories was to be starved to death, thus creating an agricultural surplus to feed Germany and urban space for the German upper class. Each division we could observe was carefully noted and counter-measures were taken. Stalin, on the other hand, had just purged his military of all top officials. During , both of these nations had their reasons for staying neutral, but once those reasons were gone, it was only a matter of time before they clashed with each other. Indeed, a month later, Soviet officials agreed to increase grain deliveries to Germany to a total of five million tons yearly. In my opinion this imposes on us only one duty, to strive more than ever after our National Socialist ideals. These were headed by Italy, with whose statesmen I am linked by ties of personal and cordial friendship. On the contrary, there are a few people who, in their deep hatred, in their senselessness, sabotage every attempt at such an understanding supported by that enemy of the world whom you all know, international Jewry. -

The Perpetrators of the November 1938 Pogrom Through German-Jewish Eyes

Chapter 4 The Perpetrators of the November 1938 Pogrom through German-Jewish Eyes Alan E. Steinweis The November 1938 pogrom, often referred to as the “Kristallnacht,” was the largest and most significant instance of organized anti-Jewish violence in Nazi Germany before the Second World War.1 In addition to the massive destruc- tion of synagogues and property, the pogrom involved the physical abuse and terrorizing of German Jews on a massive scale. German police reported an official death toll of 91, but the actual number of Jews killed was probably about ten times that many when one includes fatalities among Jews who were treated brutally during their arrest and subsequent imprisonment in Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen.2 Violence had been a normal feature of the Nazi regime’s anti-Jewish measures since 1933,3 but the scale and intensity of the Kristallnacht were unprecedented. The pogrom occurred less than one year before the outbreak of the war and the first atrocities by the Wehrmacht against Polish Jews, and less than three years before the Einsatzgruppen, Order Police, and other units began to undertake the mass murder of Jews in the Soviet Union. Knowledge about the perpetrators of the pogrom, therefore, pro- vides important context for understanding the violence that came later. To be sure, nobody has yet undertaken the extremely ambitious project to identify precisely which perpetrators of the Kristallnacht eventually would participate directly in the “Final Solution.” There certainly were many such cases, however, perhaps the most notable being Odilo Globocnik, who presided over the po- grom violence in Vienna in November 1938 and less than three years later was placed in charge of Operation Reinhardt, the mass murder of the Jews in the General Government.4 1 Many of the observations in this chapter are based on cases described and documented in the author’s book, Kristallnacht 1938 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009). -

Six the POLICE of NAZI PRAXIS

Six THE POLICE OF NAZI PRAXIS The SS was the “architect” of genocide, as part of its function as the biologically knowledgeable and modern-minded gardener of Germany’s social and political garden. Its thinking provided the theoretical framework for justifying a radical form of praxis. This praxis lay in the field of general bio-engineering, which included positive engineering (the creation and sponsoring of health and fitness), as well as its negative counterpart (the weeding out of unfit or noxious elements). There is no question, here, of reviewing in detail all SS practices: a huge amount of books and articles have already described the workings of SS endeavors. For the same reason, it would be pointless to summarize the series of events and processes that have constituted the Holocaust proper. My purpose would rather be to stress the points of passage from theory to practice, in SS thinking, and to identify the SS ideas that have fueled SS praxis. 1. Going East The spirit of SS praxis was anchored to a particular view of Germanic history, and it was summarized in a few sentences pronounced by Himmler, in 1936. In that year, he organized a ceremony to honor King Heinrich, on the occasion of the 1000th anniversary of his death, on 2 July 1936. He praised King Heinrich as an example, as a model, as a great Führer of Germany, who had fought the Slavs. And he easily assumed that King Heinrich had viewed the world in a racist perspective. In substance, Himmler expressed himself as follows: He [King Heinrich] has never forgotten that the strength of the German Volk lay in the purity of its blood and in the peasant implanting in free soil.