An Investigation of the Pigments and Materials Used in Some Mural Paintings of Mongolia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Rivers of Mongolia

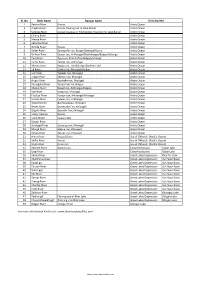

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War

Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issue 16 New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War Translation and Introduction by Sergey Radchenko1 n a freezing November afternoon in Ulaanbaatar China and Russia fell under the Mongolian sword. However, (Ulan Bator), I climbed the Zaisan hill on the south- after being conquered in the 17th century by the Manchus, Oern end of town to survey the bleak landscape below. the land of the Mongols was divided into two parts—called Black smoke from gers—Mongolian felt houses—blanketed “Outer” and “Inner” Mongolia—and reduced to provincial sta- the valley; very little could be discerned beyond the frozen tus. The inhabitants of Outer Mongolia enjoyed much greater Tuul River. Chilling wind reminded me of the cold, harsh autonomy than their compatriots across the border, and after winter ahead. I thought I should have stayed at home after all the collapse of the Qing dynasty, Outer Mongolia asserted its because my pen froze solid, and I could not scribble a thing right to nationhood. Weak and disorganized, the Mongolian on the documents I carried up with me. These were records religious leadership appealed for help from foreign countries, of Mongolia’s perilous moves on the chessboard of giants: including the United States. But the first foreign troops to its strategy of survival between China and the Soviet Union, appear were Russian soldiers under the command of the noto- and its still poorly understood role in Asia’s Cold War. These riously cruel Baron Ungern who rode past the Zaisan hill in the documents were collected from archival depositories and pri- winter of 1921. -

Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River

Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River Valley Results of the 2005 Joint American-Mongolian Expedition to Tamiryn Ulaan Khoshuu, Ogii nuur, Arkhangai aimag, Mongolia David E. Purcell and Kimberly C. Spurr Flagstaff, Arizona (USA) During the summer of 2005 an archaeological investigations, and What is known points to this area archaeological expedition jointly their results, are the focus of this as one of the most important mounted by the Silkroad Foun- article, which is a preliminary and cultural regions in the world, a fact dation of Saratoga, California, incomplete record of the project recently recognized by the U.S.A. and the Mongolian National findings. Not all of the project data UNESCO through designation of University, Ulaanbataar, investi- — including osteological analysis of the Orkhon Valley as a World gated two sites near the the burials, descriptions or maps Heritage Site in 2004 (UNESCO confluence of the Tamir River with of the graves, or analyses of the 2006). Archaeological remains the Orkhon River in the Arkhangai artifacts — is available as of this indicate the region has been aimag of central Mongolia (Fig. 1). writing. Consequently, the greater occupied since the Paleolithic (circa The expedition was permitted emphasis falls on one of the two 750,000 years before present), (Registration Number 8, issued sites. It is hoped that through the with Neolithic sites found in great June 23, 2005) by the Ministry of Silkroad Foundation, the many numbers. As early as the Neolithic Education, Culture and Science of different collections from this period a pattern developed in Mongolia. The project had multiple project can be reunited in a which groups moved southward goals: archaeological investiga- scholarly publication. -

Tuul River Mongolia

HEALTHY RIVERS FOR ALL Tuul River Basin Report Card • 1 TUUL RIVER MONGOLIA BASIN HEALTH 2019 REPORT CARD Tuul River Basin Report Card • 2 TUUL RIVER BASIN: OVERVIEW The Tuul River headwaters begin in the Lower As of 2018, 1.45 million people were living within Khentii mountains of the Khan Khentii mountain the Tuul River basin, representing 46% of Mongolia’s range (48030’58.9” N, 108014’08.3” E). The river population, and more than 60% of the country’s flows southwest through the capital of Mongolia, GDP. Due to high levels of human migration into Ulaanbaatar, after which it eventually joins the the basin, land use change within the floodplains, Orkhon River in Orkhontuul soum where the Tuul lack of wastewater treatment within settled areas, River Basin ends (48056’55.1” N, 104047’53.2” E). The and gold mining in Zaamar soum of Tuv aimag and Orkhon River then joins the Selenge River to feed Burenkhangai soum of Bulgan aimag, the Tuul River Lake Baikal in the Russian Federation. The catchment has emerged as the most polluted river in Mongolia. area is approximately 50,000 km2, and the river itself These stressors, combined with a growing water is about 720 km long. Ulaanbaatar is approximately demand and changes in precipitation due to global 470 km upstream from where the Tuul River meets warming, have led to a scarcity of water and an the Orkhon River. interruption of river flow during the spring. The Tuul River basin includes a variety of landscapes Although much research has been conducted on the including mountain taiga and forest steppe in water quality and quantity of the Tuul River, there is the upper catchment, and predominantly steppe no uniform or consistent assessment on the state downstream of Ulaanbaatar City. -

Unit Plan – Silk Road Encounters

Unit Plan – Silk Road Encounters: Real and/or Imagined? Prepared for the Central Asia in World History NEH Summer Institute The Ohio State University, July 11-29, 2016 By Kitty Lam, History Faculty, Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy, Aurora, IL [email protected] Grade Level – 9-12 Subject/Relevant Topics – World History; trade, migration, nomadism, Xiongnu, Turks, Mongols Unit length – 4-8 weeks This unit plan outlines my approach to world history with a thematic focus on the movement of people, goods and ideas. The Silk Road serves a metaphor for one of the oldest and most significant networks for long distance east-west exchange, and offers ample opportunity for students to conceptualize movement in a world historical context. This unit provides a framework for students to consider the different kinds of people who facilitated cross-cultural exchange of goods and ideas and the multiple factors that shaped human mobility. This broad unit is divided into two parts: Part A emphasizes the significance of nomadic peoples in shaping Eurasian exchanges, and Part B focuses on the relationship between religion and trade. At the end of the unit, students will evaluate the use of the term “Silk Road” to describe this trade network. Contents Part A – Huns*, Turks, and Mongols, Oh My! (Overview) -------------------------------------------------- 2 Introductory Module ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Module 1 – Let’s Get Down to Business to Defeat the Xiongnu ---------------------------------- -

Tuul River Basin Basin

GOVERNMENT OF MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT MONGOLIA I II III AND GREEN DEVELOPMENT Physical, Tuul river Socio-Economic geographical basin water Development and natural resource and and Future condition of water quality trend of the Tuul river Tuul River basin Basin IV V VI Water Water use Negative TUUL RIVER BASIN supply, water balance of the impacts on consumption- Tuul river basin basin water INTEGRATED WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN use and water resources demand, hydro- constructions VII VIII IX Main challenges River basin The organization and strategic integrated and control of objectives of the water resources the activities to river basin water management implement the Tuul management plan plan measures River Basin IWM INTEGRATED WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN plan Address: TUUL RIVER BASIN “Strengthening Integrated Water Resources Management in Mongolia” project Chingunjav Street, Bayangol District Ulaanbaatar-16050, Mongolia Tel/Fax: 362592, 363716 Website: http://iwrm.water.mn E-mail: [email protected] Ulaanbaatar 2012 Annex 1 of the Minister’s order ¹ A-102 of Environment and Green Development, dated on 03 December, 2012 TUUL RIVER BASIN INTEGRATED WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN (Phase 1, 2013-2015; Phase 2, 2016-2021) Ulaanbaatar 2012 DDC 555.7’015 Tu-90 This plan was developed within the framework of the “Strengthening Integrated Water Resources Management in Mongolia” project, funded by the Government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands at Ministry of Environment and Green Development of Mongolia Project Project Project Consulting Team National Director -

Download Download

Tuyagerel and Orkhonselenge. Mongolian Geoscientist 47 (2018) 37-44 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5564/mgs.v0i47.1064 Mongolian Geoscientist Original article ANTHROPOGENIC LANDFORM EVOLUTION REMOTED BY SATELLITE IMAGES IN TUUL RIVER BASIN 1 2* Davaagatan Tuyagerel , Alexander Orkhonselenge 1Division of Physical Geography, Institute of Geography and Geoecology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences , Ulaanbaatar 14200, Mongolia 2Laboratory of Geochemistry and Geomorphology, School of Arts and Sciences, National University of Mongolia. Ulaanbaatar 14201. Mongolia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Industrialization, construction and transportation network are abruptly grown and Received 25 June 2018 urban infrastructure is densely expanded due to rapid population growth, i.e., Accepted 26 December 2018 urbanization process is notably intensive in Ulaanbaatar as like as other cities in the world. Human activity in the overpopulated city distinctly modifies landforms and antipathetically impacts on the environment. Channel, floodplain and terraces of Tuul River draining through Ulaanbaatar have been strongly affected by the human activity. Reduction in water resource and water pollution of Tuul River are caused by bio-waste, solid waste and wastewater released from industries, thermal and electric power stations, constructions and companies operating along the river beach. This study presents landform evolution induced by human activity in Tuul River basin. More investigation is needed to infer anthropogenic -

Kherlen River the Lifeline of the Eastern Steppe

Towards Integrated River Basin Management of the Dauria Steppe Transboundary River Basins Kherlen River the Lifeline of the Eastern Steppe by Eugene Simonov, Rivers without Boundaries and Bart Wickel, Stockholm Environment Institute Satellite image of Kherlen River basin in June 2014. (NASA MODIS Imagery 25 August 2013) Please, send Your comments and suggestions for further research to Eugene Simonov [email protected]. 1 Barbers' shop on Kherlen River floodplain at Togos-Ovoo. Photo-by E.Simonov Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Executive summary ................................................................................................................................................... 8 PART I. PRESENT VALUES AND STATUS OF KHERLEN RIVER .................................................................................... 18 1 Management challenges of Mongolia’s scarce waters. .................................................................................. 18 2 The transboundary rivers of Dauria – "water wasted abroad"? ..................................................................... 21 3 Biodiversity in River basins of Dauria .............................................................................................................. 23 4 Ecosystem dynamics: Influence of climate cycles on habitats in Daurian Steppe ......................................... -

Old Turkic Script

Old Turkic script The Old Turkic script (also known as variously Göktürk script, Orkhon script, Orkhon-Yenisey script, Turkic runes) is the Old Turkic script alphabet used by the Göktürks and other early Turkic khanates Type Alphabet during the 8th to 10th centuries to record the Old Turkic language.[1] Languages Old Turkic The script is named after the Orkhon Valley in Mongolia where early Time 6th to 10th centuries 8th-century inscriptions were discovered in an 1889 expedition by period [2] Nikolai Yadrintsev. These Orkhon inscriptions were published by Parent Proto-Sinaitic(?) Vasily Radlov and deciphered by the Danish philologist Vilhelm systems Thomsen in 1893.[3] Phoenician This writing system was later used within the Uyghur Khaganate. Aramaic Additionally, a Yenisei variant is known from 9th-century Yenisei Syriac Kirghiz inscriptions, and it has likely cousins in the Talas Valley of Turkestan and the Old Hungarian alphabet of the 10th century. Sogdian or Words were usually written from right to left. Kharosthi (disputed) Contents Old Turkic script Origins Child Old Hungarian Corpus systems Table of characters Direction Right-to-left Vowels ISO 15924 Orkh, 175 Consonants Unicode Old Turkic Variants alias Unicode Unicode U+10C00–U+10C4F range See also (https://www.unicode. org/charts/PDF/U10C Notes 00.pdf) References External links Origins According to some sources, Orkhon script is derived from variants of the Aramaic alphabet,[4][5][6] in particular via the Pahlavi and Sogdian alphabets of Persia,[7][8] or possibly via Kharosthi used to write Sanskrit (cf. the inscription at Issyk kurgan). Vilhelm Thomsen (1893) connected the script to the reports of Chinese account (Records of the Grand Historian, vol. -

A History of Inner Asia

This page intentionally left blank A HISTORY OF INNER ASIA Geographically and historically Inner Asia is a confusing area which is much in need of interpretation.Svat Soucek’s book offers a short and accessible introduction to the history of the region.The narrative, which begins with the arrival of Islam, proceeds chrono- logically, charting the rise and fall of the changing dynasties, the Russian conquest of Central Asia and the fall of the Soviet Union. Dynastic tables and maps augment and elucidate the text.The con- temporary focus rests on the seven countries which make up the core of present-day Eurasia, that is Uzbekistan, Kazakstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Sinkiang, and Mongolia. Since 1991, there has been renewed interest in these countries which has prompted considerable political, cultural, economic, and religious debate.While a vast and divergent literature has evolved in consequence, no short survey of the region has been attempted. Soucek’s history of Inner Asia promises to fill this gap and to become an indispensable source of information for anyone study- ing or visiting the area. is a bibliographer at Princeton University Library. He has worked as Central Asia bibliographer at Columbia University, New York Public Library, and at the University of Michigan, and has published numerous related articles in The Journal of Turkish Studies, The Encyclopedia of Islam, and The Dictionary of the Middle Ages. A HISTORY OF INNER ASIA Princeton University Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , United Kingdom Published in the United States by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521651691 © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. -

Mongolia (Tour Participant Martin Hale)

Pallas’s Sandgrouse epitomise the wilds of Mongolia (tour participant Martin Hale) MONGOLIA 21 MAY – 4/8 JUNE 2016 LEADERS: MARK VAN BEIRS and TERBISH KHAYANKHAYRVAA The enormous, landlocked country of Mongolia is the 19th largest and the most sparsely populated fully sovereign country in the world. At 1,564,116 km² (603,909 sq mi), Mongolia is larger than the combined areas of Germany, France and Spain and holds only three million people. It is one of our classic eastern Palearctic destinations and travelling through Mongolia is a fantastic experience as the scenery is some of the best in the world. Camping is the only way to discover the real Mongolia, as there are no hotels or ger camps away from the well-known tourist haunts. On our 19 day, 3,200km off-road odyssey we wandered through the wide and wild steppes, deserts, semi-deserts, mountains, marshes and taiga of Genghis Khan’s country. The unfamiliar feeling of ‘space’ charged our batteries and we experienced both icy cold and rather hot weather. Mongolia does not yield a long birdlist, but it holds a fabulous array of attractive specialities, including many species that are only known as vagrants to Europe and North America. Spring migration was in full swing with various Siberia-bound migrants encountered at wetlands and migrant hotspots. The 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Mongolia www.birdquest-tours.com endearing Oriental Plover was the Bird of the Trip as we witnessed its heart-warming flight display several times at close range. The magnificent eye-ball to eye-ball encounter with an angry Ural Owl in the Terelj taiga will never be forgotten and we also much enjoyed the outstanding experience of observing a male Hodgson’s Bushchat in his inhospitable mountain tundra habitat. -

Gokturk Cultural History

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE Richard Dietrich, Ph.D. GOKTURK CULTURAL HISTORY Contents Religion Art Literature RELIGION Overview The GökTürk and Uighur states were characterized by religious diversity and played an important role in the history and development of religions in central Eurasia. In addition, the discovery of numerous religious texts in Old Turkic and artwork with religious subject matter has contributed greatly to modern scholars’ understanding of the history, development, beliefs and practices of Central Asian religions in general and Buddhism and Manichaeism in particular. Religion among the Gök Türk In general, the Gök Türk seem to have followed their ancestral spiritual beliefs. These included the worship of several deities, among them the sky god Tengri, to whom sacrifices of horses and sheep were offered during the fifth month of the year; a goddess associated with the household and fert ility, Umay; and a god of the road, or possibly fate, Yol Tengri. In addition to these major divinities, there were rituals related to cults of fire, earth and water, sacred forests and sacred mountains, as well as elements of ancestor worship and indications of belief in totemic animals, particularly the wolf. Another link between this world and the spirit world was the shaman, who journeyed to the spirit world in a trance in order to cure illness or foretell the future. However, it is clear that as the Gök Türk state grew and came into greater contact with other peoples they were influenced by other religious systems. One clear example of this is the Gök Türk kaghan Taghpar (or Taspar, r.