How Flowers Changed the World!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

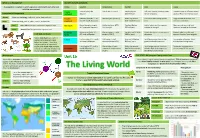

The Living World

1 The Living World MultipleChoiceQuestions (MCQs) 1 As we go from species to kingdom in a taxonomic hierarchy, the number of common characteristics (a)willdecrease (b)willincrease (c)remainsame (d) mayincreaseordecrease Ans. (a) Lower the taxa, more are the characteristic that the members within the taxon share. So, lowest taxon share the maximum number of morphological similarities, while its similarities decrease as we move towards the higher hierarchy, i.e., class, kingdom. Thus,restoftheoptionareincorrect. 2 Which of the following ‘suffixes’ used for units of classification in plants indicates a taxonomic category of ‘family’? (a) − Ales (b) − Onae (c) − Aceae (d) − Ae K ThinkingProcess Biological classification of organism is a process by which any living organism is classified into convenient categories based on some common observable characters. The categoriesareknownas taxons. Ans. (c) The name of a family, a taxon, in plants always end with suffixes aceae, e.g., Solanaceae, Cannaceae and Poaceae. Ales suffix is used for taxon ‘order’ while ae suffix is used for taxon ‘class’ and onae suffixesarenotusedatallinanyofthetaxons. 3 The term ‘systematics’ refers to (a)identificationandstudyoforgansystems (b)identificationandpreservationofplantsandanimals (c)diversityofkindsoforganismsandtheirrelationship (d) studyofhabitatsoforganismsandtheirclassification K ThinkingProcess The planet earth is full of variety of different forms of life. The number of species that are named and described are between 1.7-1.8 million. As we explore new areas, new organisms are continuously being identified, named and described on scientific basis of systematicslaiddownbytaxonomists. 1 2 (Class XI) Solutions Ans. (c) The word systematics is derived from Latin word ‘Systema’ which means systematic arrangement of organisms. Linnaeus used ‘Systema Naturae’ as a title of his publication. -

The Living World Components & Interrelationships Management

What is an Ecosystem? Biome’s climate and plants An ecosystem is a system in which organisms interact with each other and Biome Location Temperature Rainfall Flora Fauna with their environment. Tropical Centred along the Hot all year (25-30°C) Very high (over Tall trees forming a canopy; wide Greatest range of different animal Ecosystem’s Components rainforest Equator. 200mm/year) variety of species. species. Most live in canopy layer Abiotic These are non-living, such as air, water, heat and rock. Tropical Between latitudes 5°- 30° Warm all year (20-30°C) Wet + dry season Grasslands with widely spaced Large hoofed herbivores and Biotic These are living, such as plants, insects, and animals. grasslands north & south of Equator. (500-1500mm/year) trees. carnivores dominate. Flora Plant life occurring in a particular region or time. Hot desert Found along the tropics Hot by day (over 30°C) Very low (below Lack of plants and few species; Many animals are small and of Cancer and Capricorn. Cold by night 300mm/year) adapted to drought. nocturnal: except for the camel. Fauna Animal life of any particular region or time. Temperate Between latitudes 40°- Warm summers + mild Variable rainfall (500- Mainly deciduous trees; a variety Animals adapt to colder and Food Web and Chains forest 60° north of Equator. winters (5-20°C) 1500m /year) of species. warmer climates. Some migrate. Simple food chains are useful in explaining the basic principles Tundra Far Latitudes of 65° north Cold winter + cool Low rainfall (below Small plants grow close to the Low number of species. -

How to Save the World STRATEGY for WORLD CONSERVATION

How to save the world STRATEGY FOR WORLD CONSERVATION Robert Allen AX Kogan Page IUCN UNEP WW This book is based on the World Conservation Strategy prepared by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), with the advice, cooperation and financial assistance of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Illustrations: Patrick Virolle Cartoons and cover design: Oliver Duke Copyright ; I UCN-UNEP-WWE 1980 All rights reserved First published 1980 by Kogan Page Limited 120 Pentonvitte Road London NI 9JN Printed in England by MCCorquodale (Newton) Ltd.. Newton-le-Willows, Lancashire. ISBN 0 85038 314 5 (Hb) iSBN (}85038 3153 (Pb) Contents Foreword 7 Preface 9 I. Why the world needs saving now and how it can be done 11 Securing the food supply 33 Forests: saving the saviours 53 Learning to live on planel sea 71 Coming to terms with our fellow species 93 Getting organized: a strategy for conservation 121 Implementing the strategy 145 Foreword Sir Peter Scott Chairman, World Wildlife Fund The World Conservation Strategy, on which this book is based, represents several firsts in nature conservation. it is the first time that governments, non-governmental organizations and experts throughout the world have been involved in preparing a global conservation document. it is the first time that it has been clearly shown how conservation can contribute to the development objectives of governments, industry, commerce, organized labour and the professions. And it is the first time that development has been suggested as a major means of achieving conservation, instead of being viewed as an obstruction to it. -

WORLD CONSERVATION STRATEGY Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development

WORLD CONSERVATION STRATEGY Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development Prepared by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) with the advice, cooperation and financial assistance of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and in collaboration with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (F AO) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) ~ '1 IUCN WWF The Symbol The circle symbolizes the biosphere-the thin covering of the planet that contains and sustains life. The three interlocking, overlapping arrows symbolize the three objectives of conservation: - maintenance of essential ecological processes and life-support systems; - preservation of genetic diversity; - sustainable utilization of species and ecosystems. WORLD CONSERVATION STRATEGY Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development Prepared by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) with the advice, cooperation and financial assistance of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and in collaboration with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (F AO) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) 1980 ~ ~ IUCN WWF The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, UNEP or WWF concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Copyright© IUCN-UNEP-WWF 1980 All rights reserved First published 1980 Second printing 1980 ISBN 2-88032-104-2 (Bound) ISBN 2-88032-101-8 (Pack) WORLD CONSERVATION STRATEGY Contents Preamble and Guide Foreword I Preface and acknowledgements ·II Guide to the World Conservation Strategy IV Executive Summary VI World Conservation Strategy 1. -

ED 051 069 SO 001 447 TITLE Selected Bibliography and Audiovisual Materials for Environmental Education

DOCUMENT. RESURE ED 051 069 SO 001 447 TITLE Selected Bibliography and Audiovisual Materials for Environmental Education. INSTITUTION Minnesota State Dept. of Education, St. Paul. Div. of Instruction. REPORT NO XXXVIII-B-363; XXXVIII-B-365 PUB DATE [71] NOTE 46p. ?;DRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies, *Audiovisual Aids, Community Resources, Conservation Education, Ecology, Elementary Grades, *Envircnmental Education, Films, Filmstrips, *Instructional Materials, Natural Resources, Pollution, Resource Guides, Secondary Grades, *Social Problems ABSTRACT This guide to resource materials on environmental education is in two sections: 1)Selected Bibliography of Printed Materials, compiled in April, 1970; and, 2) Audio-Visual materials, Films and Filmstrips, compiled in February, 1971. 99 book annotations are given with an indicator of elementary, junior or senior high school levels. Other book information includes: publisher, copyright date, price, and Dewey Decimal classification. Also listed in this section are six periodicals and some free and inexpensive materials such as pamphlets, government documents, and bibliographies. Audiovisual aids are also arranged by level: primary, intermediate, and junior or senior high school. This last section for secondary grades is subdivided into specific topics: 1)Man and Natural Resources, 2) Population Explosions, 3) Problems of the Cities, 4) Pollution, and 5) Relationship of Man to Communities.A brief content annotation is given as well as running time, color, producer, copyright data (when available) ,rental fee and film order number from the University of Minnesota. Appended is a list of nine additional Audiovisual Rental Sources and addresses of 27 film companies. (Author/JSB) Cr' C) r^4 State of Minnesota Department of Education Code XXXVIII-B753 CP Divisiovl of Instruction April 1970 C:1 Aaj U.S DEPARTMENTOF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS THE PERSON OR RECEIVED FROM INATING IT. -

Restoring the Living Ocean: the Time Is Now

www.ecologicalcitizen.net LONG ARTICLE Restoring the living ocean: The time is now The first part of this two-part essay looks at the destruction that industrial fishing has Eileen Crist unleashed on the global ocean. Human beings have forgotten the living abundance that the seas once harboured. A conglomerate of anthropocentric concepts, mega machines, About the author international fishing fleets and consumerist oblivion has laid waste to that abundance, and Eileen has been teaching brought extinction, death and suffering to marine beings. The subject matter of part two at Virginia Tech in the Department of Science and is deep-sea mining, which is under preparation for commercial launching. Like industrial Technology in Society since fishing, it must be stopped. What is at stake at this historic moment is not only the fate of 1997. She has written and the living ocean, but who we are and who we choose to be as humanity on this planet. co-edited numerous papers and books, with her work Part 1: Sweet delight as if massively destroying ecosystems focusing on biodiversity were the most normal thing ever devised. loss and destruction of wild places, along with pathways and endless night The global fishing industry operates more to halt these trends. Eileen vessels than there are numbers of fish left to lives in Blacksburg, VA, USA. he global ocean is imperilled. be caught, while the incalculable numbers What remains of marine life of slaughtered bystanders are labelled ‘by- Citation abundance, a tiny fraction of catch’ as if they are killed by mistake. Crist E (2019) Restoring the T living ocean: The time is now. -

Extensions of Remar.Ks

July 8, 1970 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 23329 EXTENSIONS OF REMAR.KS BRIGHT FUTURE FOR NORTHEAST the Commonwealth, the Department of Com With a good reputation for action it is diffi ERN PENNSYLVANIA munity Affairs and the Department of Com cult to slow the momentum of a winner. merce wm benefit the northeast and other And it has not been done With magic, With regions as they work in the seventies. rabbits in a ha.t--not by any one local, state HON. HUGH SCOTT Once a Bureau within the Department of or federal agency, but with the combined ef Commerce, the Department of Community forts of responsible people, hardworking, OF PENNSYLVANIA Affairs has blossomed into an effective backed by substantial private investment- IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES agency for direct involvement in vital areas with faith, dimes, dollars, of people who be Wednesday, July 8, 1970 that have mushroomed into prominence in lieved it could be done. recent years. I believe it is an unheralded Specifically, the pace was set Dy successful Mr. SCO'IT. Mr President, on June 6, blessing for the citizens of the Common industrial expansion and relocation pro 1970, the secretary of commerce of Penn wealth of Pennsylvania to have such close grams. PIDA activity in a seven county area sylvania, Hon. William T. Schmidt, de cooperation and such common dedication of northeastern Pennsylvania resulted in 241 livered a speech to the conference of the among the personnel of two organiz.a.tions loans in the amount of $58,760,000 since 1956 that can provide so much assistance to them. -

South Orlando Baptist Church LIBRARY RECORDS by SUBJECT

South Orlando Baptist Church LIBRARY RECORDS BY SUBJECT Page 1 Friday, November 15, 2013 Find all records where any portion of Basic Fields (Title, Author, Subjects, Summary, & Comments) like '' Subject Title Classification Author Accession # Abandoned children Fiction A cry in the dark (Summerhill Secrets #5) JF Lewis, Beverly 6543 Abandoned houses Fiction Julia's hope (The Wortham Family Series #1) F Kelly, Leisha 5343 Abolitionists Frederick Douglass (Black Americans of Achievement) JB Russell, Sharman Apt. 8173 Abortion Fiction Choice summer (Nikki Sheridan Series #1) YA F Brinkerhoff, Shirley 7970 Shades of blue F Kingsbury, Karen 8823 Tilly : the novel F Peretti, Frank E. 6204 Abortion Moral and ethical aspects Abortion : a rational look at an emotional issue 241 Sproul, R. C. (Robert Charles) 1296 Abraham (Biblical patriarch) Abraham and his big family [videorecording] VHS C220.95 Walton, John H. 5221 Abraham, man of faith J221.92 Rives, Elsie 1513 Created to be God's friend : how God shapes those He loves 248.4 Blackaby, Henry T. 4008 Dragons (Face to face) J398.24 Dixon, Dougal 8517 The story of Abraham (Great Bible Stories) C221.92 Nodel, Maxine 3724 Abused children Fiction Looking for Cassandra Jane F Carlson, Melody 6052 Abused wives Fiction A place called Wiregrass F Morris, Michael 7881 Wings of a dove F Bush, Beverly 2498 Abused women Fiction Sharon's hope F Coyle, Neva 3706 Acadians Fiction The beloved land (Song of Acadia #5) F Oke, Janette 3910 The distant beacon (Song of Acadia #4) F Oke, Janette 3690 The innocent libertine (Heirs of Acadia #2) F Bunn, T. -

Nhbs Monthly Catalogue New and Forthcoming Titles Issue: 2011/03 March 2011 [email protected] +44 (0)1803 865913

nhbs monthly catalogue new and forthcoming titles Issue: 2011/03 March 2011 www.nhbs.com [email protected] +44 (0)1803 865913 Welcome to the March 2011 edition of the NHBS Monthly Catalogue. This monthly Zoology: update contains all of the wildlife, science and environment titles added to nhbs.com in Mammals the last month. Birds Customer testimonials: read what our customers say about NHBS. Reptiles & Amphibians Fishes Our annual Backlist Bargains has just one month to run - an annual opportunity to Invertebrates buy best-selling backlist titles at an average discount of 40% (until 31 March 2011). Palaeontology Editor's Picks - New in Stock this Month Marine & Freshwater Biology General Natural History ● The Rise of Fishes Regional & Travel ● Urban Ecology Botany & Plant Science ● Fossil Spiders Animal & General Biology ● The Birds of Panama Evolutionary Biology ● A Field Guide to the Butterflies of Singapore ● The Dance of Air and Sea Ecology ● A Dipterist's Handbook Habitats & Ecosystems ● The Crossley ID Guide: Eastern Birds Conservation & Biodiversity ● British and Irish Moths: An Illustrated Guide to Selected Difficult Species Environmental Science ● Lives of Conifers Physical Sciences ● The Anatomy of Palms Sustainable Development ● Conservation Biogeography ● RSPB Guide to Digital Wildlife Photography Data Analysis Reference Find out more about services for libraries and organisations: NHBS LibraryPro Best wishes, -The NHBS Team View this Monthly Catalogue as a web page or save/print it as a .pdf document. Mammals Go to subject web page Bats 112 pages | Col photos, illus | Natural Phil Richardson History Museum Phil Richardson uses his experiences of bat watching around the world to describe their complex Pbk | 2011 | 9565092756 | #190227A | life cycles. -

Interdependence of Biodiversity and Development Under Global Change

Secretariat of the CBD Technical Series No. 54 Convention on Biological Diversity 54 Interdependence of Biodiversity and Development Under Global Change CBD Technical Series No. 54 Interdependence of Biodiversity and Development Under Global Change Published by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity ISBN: 92-9225-296-8 Copyright © 2010, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity concern- ing the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views reported in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Convention on Biological Diversity. This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holders, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The Secretariat of the Convention would appreciate receiving a copy of any publications that use this document as a source. Citation Ibisch, P.L. & A. Vega E., T.M. Herrmann (eds.) 2010. Interdependence of biodiversity and development under global change. Technical Series No. 54. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal (second corrected edition). Financial support has been provided by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development For further information, please contact: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity World Trade Centre 413 St. Jacques Street, Suite 800 Montreal, Quebec, Canada H2Y 1N9 Phone: +1 514 288 2220 Fax: +1 514 288 6588 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cbd.int Typesetting: Em Dash Design Cover photos (top to bottom): Agro-ecosystem used for thousands of years in the vicinities of the Mycenae palace (located about 90 km south-west of Athens, in the north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece). -

Annual Report 2011-2012

Department of Physics Astronomy& ANNUAL REPORT 2011-2012 ANNUAL REPORT 2011-12 Annual Report 2011-12-Final-.indd 1 11/30/12 3:23 PM UCLA Physics and Astronomy Department 2011-2012 Chair James Rosenzweig Chief Administrative Officer Will Spencer Feature Article Alex Levine Design Mary Jo Robertson © 2012 by the Regents of the University of California All rights reserved. Requests for additional copies of the publication UCLA Department of Physics and Astronomy 2011-2012 Annual Report may be sent to: Office of the Chair UCLA Department of Physics and Astronomy 430 Portola Plaza Box 951547 For more information on the Department see our website: http://www.pa.ucla.edu/ Los Angeles California 90095-1547 UCLA DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS & ASTRONOMY Annual Report 2011-12-Final-.indd 2 11/30/12 3:23 PM Department of Physics Astronomy& 2011-2012 Annual Report UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES ANNUAL REPORT 2011-12 Annual Report 2011-12-Final-.indd 3 11/30/12 3:23 PM CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLE: EXPLORING THE PHYSICAL FOUNDATION OF EMERGENT PHENOMENA P.7 GIVING TO THE DEPARTMENT P.14 ‘BRILLIANT’ SUPERSTAR ASTRONOMERS P.16 ASTRONOMY & ASTROPHYSICS P.17 ASTROPARTICLE PHYSICS P.24 PHYSICS RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS P.27 PHYSICS & ASTRONOMY FACULTY/RESEARCHERS P.45 NEW DEPARTMENT FACULTY P.46 RALPH WUERKER 1929-2012 P.47 UCLA ALUMNI P.48 DEPARTMENT NEWS P.49 OUTREACH-ASTRONOMY LIVE P.51 ACADEMICS CREATING AND UPGRADING TEACHING LABS P.52 WOMEN IN SCIENCE P.53 GRADUATION 2011-2012 P.54-55 Annual Report 2011-12-Final-.indd 4 11/30/12 3:24 PM Message from the Chair As Chair of the UCLA Department of Physics and Astronomy, it is with pleasure that I present to you our 2011-12 Annual Report. -

The Tuma Underworld of Love. Erotic and Other Narrative Songs of The

The Tuma Underworld of Love Erotic and other narrative songs of the Trobriand Islanders and their spirits of the dead Culture andCulture Language Use Gunter Senft guest IP: 195.169.108.24 On: Tue, 01 Aug 2017 13:36:03 5 John Benjamins Publishing Company The Tuma Underworld of Love Underworld Tuma The guest IP: 195.169.108.24 On: Tue, 01 Aug 2017 13:36:03 Culture and Language Use Studies in Anthropological Linguistics CLU-SAL publishes monographs and edited collections, culturally oriented grammars and dictionaries in the cross- and interdisciplinary domain of anthropological linguistics or linguistic anthropology. The series offers a forum for anthropological research based on knowledge of the native languages of the people being studied and that linguistic research and grammatical studies must be based on a deep understanding of the function of speech forms in the speech community under study. For an overview of all books published in this series, please see http://benjamins.com/catalog/clu Editor Gunter Senft Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen guest IP: 195.169.108.24 On: Tue, 01 Aug 2017 13:36:03 Volume 5 The Tuma Underworld of Love. Erotic and other narrative songs of the Trobriand Islanders and their spirits of the dead by Gunter Senft The Tuma Underworld of Love Erotic and other narrative songs of the Trobriand Islanders and their spirits of the dead Gunter Senft Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics guest IP: 195.169.108.24 On: Tue, 01 Aug 2017 13:36:03 John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984.