Amicus Curiae Briefs from Harvard Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nonhuman Rights to Personhood

Pace Environmental Law Review Volume 30 Issue 3 Summer 2013 Article 10 July 2013 Nonhuman Rights to Personhood Steven M. Wise Nonhuman Rights Project Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pelr Part of the Animal Law Commons, and the Environmental Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven M. Wise, Nonhuman Rights to Personhood, 30 Pace Envtl. L. Rev. 1278 (2013) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pelr/vol30/iss3/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Environmental Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYSON LECTURE Nonhuman Rights to Personhood STEVEN M. WISE I. INTRODUCTION Thank you all for joining us for the second Dyson Lecture of 2012. We were very lucky to have a first Dyson Lecture, and we will have an even more successful lecture this time. We have a very distinguished person I will talk about in just a second. I’m David Cassuto, a Pace Law School professor. I teach among other things, Animal Law, and that is why I am very familiar with Professor Wise’s work. I want to say a few words about the Dyson Lecture. The Dyson Distinguished Lecture was endowed in 1982 by a gift from the Dyson Foundation, which was made possible through the generosity of the late Charles Dyson, a 1930 graduate, trustee, and long-time benefactor of Pace University. The principle aim of the Dyson Lecture is to encourage and make possible scholarly legal contributions of high quality in furtherance of Pace Law School’s educational mission and that is very much what we are going to have today. -

COURT of APPEALS of the STATE of NEW YORK ------X in the Matter of a Proceeding Under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus

COURT OF APPEALS OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------x In the Matter of a Proceeding under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on Index Nos. 162358/15 behalf of TOMMY, (New York County); Petitioner-Appellant, 150149/16 (New York -against- County) PATRICK C. LAVERY, individually and as an of Circle L Trailer Sales, Inc., DIANE LAVERY, and CIRCLE L TRAILER SALES, INC., Respondents-Respondents, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on behalf of KIKO, Petitioner-Appellant, -against- CARMEN PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., CHRISTIE E. PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., and THE PRIMATE SANCTUARY, INC., Respondents-Respondents. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------x MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR PERMISSION TO APPEAL TO THE COURT OF APPEALS Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Steven M. Wise, Esq. 5 Dunhill Road (of the Bar of the State of New Hyde Park, New York Massachusetts) 11040 By Permission of the Court (516) 747-4726 5195 NW 112th Terrace [email protected] Coral Springs, Florida 33076 (954) 648-9864 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Authorities ................................................................................... iv Argument .................................................................................................... 1 I. Preliminary Statement -

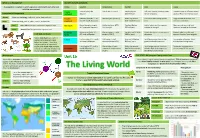

The Living World

1 The Living World MultipleChoiceQuestions (MCQs) 1 As we go from species to kingdom in a taxonomic hierarchy, the number of common characteristics (a)willdecrease (b)willincrease (c)remainsame (d) mayincreaseordecrease Ans. (a) Lower the taxa, more are the characteristic that the members within the taxon share. So, lowest taxon share the maximum number of morphological similarities, while its similarities decrease as we move towards the higher hierarchy, i.e., class, kingdom. Thus,restoftheoptionareincorrect. 2 Which of the following ‘suffixes’ used for units of classification in plants indicates a taxonomic category of ‘family’? (a) − Ales (b) − Onae (c) − Aceae (d) − Ae K ThinkingProcess Biological classification of organism is a process by which any living organism is classified into convenient categories based on some common observable characters. The categoriesareknownas taxons. Ans. (c) The name of a family, a taxon, in plants always end with suffixes aceae, e.g., Solanaceae, Cannaceae and Poaceae. Ales suffix is used for taxon ‘order’ while ae suffix is used for taxon ‘class’ and onae suffixesarenotusedatallinanyofthetaxons. 3 The term ‘systematics’ refers to (a)identificationandstudyoforgansystems (b)identificationandpreservationofplantsandanimals (c)diversityofkindsoforganismsandtheirrelationship (d) studyofhabitatsoforganismsandtheirclassification K ThinkingProcess The planet earth is full of variety of different forms of life. The number of species that are named and described are between 1.7-1.8 million. As we explore new areas, new organisms are continuously being identified, named and described on scientific basis of systematicslaiddownbytaxonomists. 1 2 (Class XI) Solutions Ans. (c) The word systematics is derived from Latin word ‘Systema’ which means systematic arrangement of organisms. Linnaeus used ‘Systema Naturae’ as a title of his publication. -

ASEBL Journal

January 2019 Volume 14, Issue 1 ASEBL Journal Association for the Study of EDITOR (Ethical Behavior)•(Evolutionary Biology) in Literature St. Francis College, Brooklyn Heights, N.Y. Gregory F. Tague, Ph.D. ▬ ~ GUEST CO-EDITOR ISSUE ON GREAT APE PERSONHOOD Christine Webb, Ph.D. ~ (To Navigate to Articles, Click on Author’s Last Name) EDITORIAL BOARD — Divya Bhatnagar, Ph.D. FROM THE EDITORS, pg. 2 Kristy Biolsi, Ph.D. ACADEMIC ESSAY Alison Dell, Ph.D. † Shawn Thompson, “Supporting Ape Rights: Tom Dolack, Ph.D Finding the Right Fit Between Science and the Law.” pg. 3 Wendy Galgan, Ph.D. COMMENTS Joe Keener, Ph.D. † Gary L. Shapiro, pg. 25 † Nicolas Delon, pg. 26 Eric Luttrell, Ph.D. † Elise Huchard, pg. 30 † Zipporah Weisberg, pg. 33 Riza Öztürk, Ph.D. † Carlo Alvaro, pg. 36 Eric Platt, Ph.D. † Peter Woodford, pg. 38 † Dustin Hellberg, pg. 41 Anja Müller-Wood, Ph.D. † Jennifer Vonk, pg. 43 † Edwin J.C. van Leeuwen and Lysanne Snijders, pg. 46 SCIENCE CONSULTANT † Leif Cocks, pg. 48 Kathleen A. Nolan, Ph.D. † RESPONSE to Comments by Shawn Thompson, pg. 48 EDITORIAL INTERN Angelica Schell † Contributor Biographies, pg. 54 Although this is an open-access journal where papers and articles are freely disseminated across the internet for personal or academic use, the rights of individual authors as well as those of the journal and its editors are none- theless asserted: no part of the journal can be used for commercial purposes whatsoever without the express written consent of the editor. Cite as: ASEBL Journal ASEBL Journal Copyright©2019 E-ISSN: 1944-401X [email protected] www.asebl.blogspot.com Member, Council of Editors of Learned Journals ASEBL Journal – Volume 14 Issue 1, January 2019 From the Editors Shawn Thompson is the first to admit that he is not a scientist, and his essay does not pretend to be a scientific paper. -

The Three Phases of Arendt's Theory of Totalitarianism*

The Three Phases of Arendt's Theory of Totalitarianism* X~1ANNAH Arendt's The Origins of Totalitarianism, first published in 1951, is a bewilderingly wide-ranging work, a book about much more than just totalitarianism and its immediate origins.' In fact, it is not really about those immediate origins at all. The book's peculiar organization creates a certain ambiguity regarding its intended subject-matter and scope.^ The first part, "Anti- semitism," tells the story of tbe rise of modern, secular anti-Semi- tism (as distinct from what the author calls "religious Jew-hatred") up to the turn of the twentieth century, and ends with the Drey- fus affair in Erance—a "dress rehearsal," in Arendt's words, for things still worse to come (10). The second part, "Imperialism," surveys an assortment of pathologies in the world politics of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, leading to (but not direcdy involving) the Eirst World War. This part of the book examines the European powers' rapacious expansionist policies in Africa and Asia—in which overseas investment became the pre- text for raw, openly racist exploitation—and the concomitant emergence in Central and Eastern Europe of "tribalist" ethnic movements whose (failed) ambition was the replication of those *Earlier versions of this essay were presented at the University of Virginia and at the conference commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of The Origins of Toudilarianism hosted by the Hannah Arendt-Zentrum at Carl Ossietzky University in Oldenburg, Ger- many. I am grateful to Joshua Dienstag and Antonia Gnmenberg. respectively, for arrang- ing these (wo occasions, and also to the inembers of the audience at each—especially Lawrie Balfour, Wolfgang Heuer, George KJosko, Allan Megili, Alfons Sollner, and Zoltan Szankay—for their helpful commeiiLs and criticisms. -

Legal Personhood for Animals and the Intersectionality of the Civil & Animal Rights Movements

Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 5 2016 Free Tilly?: Legal Personhood for Animals and the Intersectionality of the Civil & Animal Rights Movements Becky Boyle Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijlse Part of the Law Commons Publication Citation Becky Boyle, Free Tilly?: Legal Personhood for Animals and the Intersectionality of the Civil & Animal Rights Movements, 4 Ind. J. L. & Soc. Equality 169 (2016). This Student Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality Volume 4, Issue 2 FREE TILLY?: LEGAL PERSONHOOD FOR ANIMALS AND THE INTERSECTIONALITY OF THE CIVIL & ANIMAL RIGHTS MOVEMENTS BECKY BOYLE INTRODUCTION In February 2012, the District Court for the Southern District of California heard Tilikum v. Sea World, a landmark case for animal legal defense.1 The organization People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) filed a suit as next friends2 of five orca whales demanding their freedom from the marine wildlife entertainment park known as SeaWorld.3 The plaintiffs—Tilikum, Katina, Corky, Kasatka, and Ulises—were wild born and captured to perform at SeaWorld’s Shamu Stadium.4 They sought declaratory and injunctive relief for being held by SeaWorld in violation of slavery and involuntary servitude provisions of the Thirteenth Amendment.5 It was the first court in U.S. -

The Living World Components & Interrelationships Management

What is an Ecosystem? Biome’s climate and plants An ecosystem is a system in which organisms interact with each other and Biome Location Temperature Rainfall Flora Fauna with their environment. Tropical Centred along the Hot all year (25-30°C) Very high (over Tall trees forming a canopy; wide Greatest range of different animal Ecosystem’s Components rainforest Equator. 200mm/year) variety of species. species. Most live in canopy layer Abiotic These are non-living, such as air, water, heat and rock. Tropical Between latitudes 5°- 30° Warm all year (20-30°C) Wet + dry season Grasslands with widely spaced Large hoofed herbivores and Biotic These are living, such as plants, insects, and animals. grasslands north & south of Equator. (500-1500mm/year) trees. carnivores dominate. Flora Plant life occurring in a particular region or time. Hot desert Found along the tropics Hot by day (over 30°C) Very low (below Lack of plants and few species; Many animals are small and of Cancer and Capricorn. Cold by night 300mm/year) adapted to drought. nocturnal: except for the camel. Fauna Animal life of any particular region or time. Temperate Between latitudes 40°- Warm summers + mild Variable rainfall (500- Mainly deciduous trees; a variety Animals adapt to colder and Food Web and Chains forest 60° north of Equator. winters (5-20°C) 1500m /year) of species. warmer climates. Some migrate. Simple food chains are useful in explaining the basic principles Tundra Far Latitudes of 65° north Cold winter + cool Low rainfall (below Small plants grow close to the Low number of species. -

Publications Catalogue 2015–16

Publications Catalogue 2015 –16 Vogue 100 New titles A Century of Style Robin Muir While principally a fashion magazine, Vogue has never been just that. It has assumed a central and vital role on the cultural stage, with a history that spans the most inventive decades in fashion and taste, and in the arts and society. Published to mark the magazine’s centenary, and accompanying a major exhibition, this book celebrates the twentieth century and beyond with an authoritative and discriminating eye. In more than 2,000 issues, British Vogue has acted as a cultural barometer, putting fashion in the context of the wider world – how we dress, how we entertain, what we eat, listen to, watch, who leads us, excites us and inspires us. The century’s most talented photographers, Lee Miller, Norman Parkinson, Cecil Beaton, Irving Penn, David Bailey, Snowdon and Mario Testino among them, have contributed to it. In 1916, when the First World War made transatlantic shipments of American Vogue impossible, its proprietor, Condé Nast, authorised a British edition. It was an immediate success, and over the following ten decades cover Provisional of uninterrupted publication continued to mirror its times – the austerity and optimism that followed two world wars, the ‘Swinging London’ scene 310 x 254 mm, 304 pages of the sixties, the radical seventies, the image-conscious eighties – and in Over 300 illustrations its second century remains at the cutting edge of photography and design. ISBN 978 1 85514 561 0 Decade by decade, Vogue 100 celebrates the greatest moments in Price £40 TBC (hardback) fashion, beauty and portrait photography. -

Rossmoor Fund Expands Board to Keep up with Its Growing Workload

ROSSMOOR NEWS WedNesday, august 21, 2013 WalNut creek, califorNia Volume 47, No. 23 • 50 ceNts grading for the courts Shred Day Saturday allows onsite witnessed destruction Rossmoor will sponsor another on-site witness-destruction shred day on Saturday, Aug. 24, from 10 a.m. until 1 p.m. in the Gateway parking lot. This event is sponsored by the Golden Rain Foundation. The cost is $5 per file box or 30 pounds. Only cash is accept- ed. Residents can witness the destruction of their confidential in- formation and files by Shred Works, a AAA-certified shredding company. All the shredded material is recycled. Only paper is accepted. There is no need to worry about re- moving staples or paper clips. Help will be available to unload the material from the car. For information, call Shred Works at 1-800-81SHRED, or email Kyle Taylor at [email protected]. How to use Dial-a-Bus for early and late trips In Rossmoor and downtown News photo by Mike DiCarlo esidents who go to the Fitness Center at Del Valle for an early morning workout, need to get to a meeting at Buckeye tennis court construction under way RGateway Clubhouse or who need to catch BART for work, are advised to call Rossmoor’s Dial-a-Bus for their There’s lots of activity at the Buckeye tennis court site. Last week the demolition work was transportation. The number is 988-7676 finished and work began on the rough grading for the two new courts. All the courts at Buck- Residents who want to dine at Creekside Grill or venture eye are closed to play so players have been using the two old courts on Rossmoor Parkway. -

Annual Report 2017-2018.Pdf

COLD SPRING HARBOR CENTRAL SCHOOL DISTRICT ANNUAL REPORT 2017-2018 October 9, 2018 Cold Spring Harbor Central School District The 2017-2018 school year was one in which we created a variety of new learning experiences for our students, all behind the efforts of Cold Spring Harbor teachers and leaders to prepare them for the future. Following the vision driving the district’s board of education goals, all teachers and leaders continued to build an awareness of the Next Generation Learning Standards through a diverse professional development workshops offered by staff developers from around the country and members of the Cold Spring Harbor faculty. Professional development occurred in numerous content areas such as English Language Arts, math, social studies, science, and technology. Teachers also received professional learning in the revised New York State Standards for the Arts. These efforts continue to support many goals including the district’s work in building authentic research experiences for all students in kindergarten through graduation. In addition, our Science Research Program continued to flourish and its expansion provided students with practical experiences and even an opportunity to highlight their work at the Science Research Symposium at the high school, a true example of providing students with opportunities to share high level research with their peers and the community. While there are many highlights to the school year in relation to the district’s goals in the area of technology, the Creative Learning Labs assembled at the two elementary buildings provided students, teachers, and even parents the chance to experience a truly redefined classroom. Designed by teachers and leaders, these state-of-the-art spaces outfitted with flexible furniture, afforded students with the ability to experience enhanced and differentiated learning environments. -

Lexical Semantic Analysis in Natural Language Text

Lexical Semantic Analysis in Natural Language Text Nathan Schneider Language Technologies Institute School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University ◇ July 28, 2014 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy in language and information technologies Abstract Computer programs that make inferences about natural language are easily fooled by the often haphazard relationship between words and their meanings. This thesis develops Lexical Semantic Analysis (LxSA), a general-purpose framework for describing word groupings and meanings in context. LxSA marries comprehensive linguistic annotation of corpora with engineering of statistical natural lan- guage processing tools. The framework does not require any lexical resource or syntactic parser, so it will be relatively simple to adapt to new languages and domains. The contributions of this thesis are: a formal representation of lexical segments and coarse semantic classes; a well-tested linguistic annotation scheme with detailed guidelines for identifying multi- word expressions and categorizing nouns, verbs, and prepositions; an English web corpus annotated with this scheme; and an open source NLP system that automates the analysis by statistical se- quence tagging. Finally, we motivate the applicability of lexical se- mantic information to sentence-level language technologies (such as semantic parsing and machine translation) and to corpus-based linguistic inquiry. i I, Nathan Schneider, do solemnly swear that this thesis is my own To my parents, who gave me language. work, and that everything therein is, to the best of my knowledge, true, accurate, and properly cited, so help me Vinken. § ∗ In memory of Charles “Chuck” Fillmore, one of the great linguists. -

How to Save the World STRATEGY for WORLD CONSERVATION

How to save the world STRATEGY FOR WORLD CONSERVATION Robert Allen AX Kogan Page IUCN UNEP WW This book is based on the World Conservation Strategy prepared by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), with the advice, cooperation and financial assistance of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Illustrations: Patrick Virolle Cartoons and cover design: Oliver Duke Copyright ; I UCN-UNEP-WWE 1980 All rights reserved First published 1980 by Kogan Page Limited 120 Pentonvitte Road London NI 9JN Printed in England by MCCorquodale (Newton) Ltd.. Newton-le-Willows, Lancashire. ISBN 0 85038 314 5 (Hb) iSBN (}85038 3153 (Pb) Contents Foreword 7 Preface 9 I. Why the world needs saving now and how it can be done 11 Securing the food supply 33 Forests: saving the saviours 53 Learning to live on planel sea 71 Coming to terms with our fellow species 93 Getting organized: a strategy for conservation 121 Implementing the strategy 145 Foreword Sir Peter Scott Chairman, World Wildlife Fund The World Conservation Strategy, on which this book is based, represents several firsts in nature conservation. it is the first time that governments, non-governmental organizations and experts throughout the world have been involved in preparing a global conservation document. it is the first time that it has been clearly shown how conservation can contribute to the development objectives of governments, industry, commerce, organized labour and the professions. And it is the first time that development has been suggested as a major means of achieving conservation, instead of being viewed as an obstruction to it.