World Hau Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geological Timeline

Geological Timeline In this pack you will find information and activities to help your class grasp the concept of geological time, just how old our planet is, and just how young we, as a species, are. Planet Earth is 4,600 million years old. We all know this is very old indeed, but big numbers like this are always difficult to get your head around. The activities in this pack will help your class to make visual representations of the age of the Earth to help them get to grips with the timescales involved. Important EvEnts In thE Earth’s hIstory 4600 mya (million years ago) – Planet Earth formed. Dust left over from the birth of the sun clumped together to form planet Earth. The other planets in our solar system were also formed in this way at about the same time. 4500 mya – Earth’s core and crust formed. Dense metals sank to the centre of the Earth and formed the core, while the outside layer cooled and solidified to form the Earth’s crust. 4400 mya – The Earth’s first oceans formed. Water vapour was released into the Earth’s atmosphere by volcanism. It then cooled, fell back down as rain, and formed the Earth’s first oceans. Some water may also have been brought to Earth by comets and asteroids. 3850 mya – The first life appeared on Earth. It was very simple single-celled organisms. Exactly how life first arose is a mystery. 1500 mya – Oxygen began to accumulate in the Earth’s atmosphere. Oxygen is made by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) as a product of photosynthesis. -

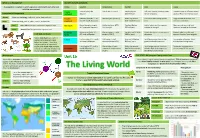

The Living World

1 The Living World MultipleChoiceQuestions (MCQs) 1 As we go from species to kingdom in a taxonomic hierarchy, the number of common characteristics (a)willdecrease (b)willincrease (c)remainsame (d) mayincreaseordecrease Ans. (a) Lower the taxa, more are the characteristic that the members within the taxon share. So, lowest taxon share the maximum number of morphological similarities, while its similarities decrease as we move towards the higher hierarchy, i.e., class, kingdom. Thus,restoftheoptionareincorrect. 2 Which of the following ‘suffixes’ used for units of classification in plants indicates a taxonomic category of ‘family’? (a) − Ales (b) − Onae (c) − Aceae (d) − Ae K ThinkingProcess Biological classification of organism is a process by which any living organism is classified into convenient categories based on some common observable characters. The categoriesareknownas taxons. Ans. (c) The name of a family, a taxon, in plants always end with suffixes aceae, e.g., Solanaceae, Cannaceae and Poaceae. Ales suffix is used for taxon ‘order’ while ae suffix is used for taxon ‘class’ and onae suffixesarenotusedatallinanyofthetaxons. 3 The term ‘systematics’ refers to (a)identificationandstudyoforgansystems (b)identificationandpreservationofplantsandanimals (c)diversityofkindsoforganismsandtheirrelationship (d) studyofhabitatsoforganismsandtheirclassification K ThinkingProcess The planet earth is full of variety of different forms of life. The number of species that are named and described are between 1.7-1.8 million. As we explore new areas, new organisms are continuously being identified, named and described on scientific basis of systematicslaiddownbytaxonomists. 1 2 (Class XI) Solutions Ans. (c) The word systematics is derived from Latin word ‘Systema’ which means systematic arrangement of organisms. Linnaeus used ‘Systema Naturae’ as a title of his publication. -

Beyond Planet Earth: the Future of Planet Earth: Beyond 20 22 18 14 12 6 8 4 ; and the of 35Th the Anniversary 3

Member Magazine Fall 2011 Vol. 36 No. 4 Searching For Life on Mars How to Opening Build November 19 a Lunar BEYOND Elevator PLANET EARTH: THE FUTURE OF SPACE EXPLORATION Astrophysics at the Museum 2 News at the Museum 3 From the Even for those of us long past our school years, fall of you participated. Based on that work, the Museum More Stars Shine Brighter With Museum To Offer always feels like “back to school”—a time for new has restructured and enhanced its program to bring President ventures and new adventures. The most exciting it more fully in line with Members’ lives. Hayden Planetarium Upgrade Science Teaching Degree new venture at the Museum is our Master of Arts Membership categories will now more closely Ellen V. Futter in Teaching (MAT) program, which marks the first reflect the kinds of households that you are part This fall, the Museum is launching a Master time that an institution other than a university of, with new Family and Adult tracks that will of Arts in Teaching (MAT) program, marking or college will offer a master’s program for science allow us to tailor programs, services, and benefits. the first time that an institution other than teachers. Please read more about this pioneering And, moving forward, there will be an increased a university or college will offer such a program initiative on page 3. emphasis on communication, including keeping for science teachers. Fall 2011 brings a full slate of exciting offerings in closer touch with Members through electronic The pioneering 15-month program is for the public, including our thrilling new means, including a new digital membership. -

The Living World Components & Interrelationships Management

What is an Ecosystem? Biome’s climate and plants An ecosystem is a system in which organisms interact with each other and Biome Location Temperature Rainfall Flora Fauna with their environment. Tropical Centred along the Hot all year (25-30°C) Very high (over Tall trees forming a canopy; wide Greatest range of different animal Ecosystem’s Components rainforest Equator. 200mm/year) variety of species. species. Most live in canopy layer Abiotic These are non-living, such as air, water, heat and rock. Tropical Between latitudes 5°- 30° Warm all year (20-30°C) Wet + dry season Grasslands with widely spaced Large hoofed herbivores and Biotic These are living, such as plants, insects, and animals. grasslands north & south of Equator. (500-1500mm/year) trees. carnivores dominate. Flora Plant life occurring in a particular region or time. Hot desert Found along the tropics Hot by day (over 30°C) Very low (below Lack of plants and few species; Many animals are small and of Cancer and Capricorn. Cold by night 300mm/year) adapted to drought. nocturnal: except for the camel. Fauna Animal life of any particular region or time. Temperate Between latitudes 40°- Warm summers + mild Variable rainfall (500- Mainly deciduous trees; a variety Animals adapt to colder and Food Web and Chains forest 60° north of Equator. winters (5-20°C) 1500m /year) of species. warmer climates. Some migrate. Simple food chains are useful in explaining the basic principles Tundra Far Latitudes of 65° north Cold winter + cool Low rainfall (below Small plants grow close to the Low number of species. -

Greening Wildlife Documentary’, in Libby Lester and Brett Hutchins (Eds) Environmental Conflict and the Media, New York: Peter Lang

Morgan Richards (forthcoming 2013) ‘Greening Wildlife Documentary’, in Libby Lester and Brett Hutchins (eds) Environmental Conflict and the Media, New York: Peter Lang. GREENING WILDLIFE DOCUMENTARY Morgan Richards The loss of wilderness is a truth so sad, so overwhelming that, to reflect reality, it would need to be the subject of every wildlife film. That, of course, would be neither entertaining nor ultimately dramatic. So it seems that as filmmakers we are doomed either to fail our audience or fail our cause. — Stephen Mills (1997) Five years before the BBC’s Frozen Planet was first broadcast in 2011, Sir David Attenborough publically announced his belief in human-induced global warming. “My message is that the world is warming, and that it’s our fault,” he declared on the BBC’s Ten O’Clock News in May 2006. This was the first statement, both in the media and in his numerous wildlife series, in which he didn’t hedge his opinion, choosing to focus on slowly accruing scientific data rather than ruling definitively on the causes and likely environmental impacts of climate change. Frozen Planet, a seven-part landmark documentary series, produced by the BBC Natural History Unit and largely co-financed by the Discovery Channel, was heralded by many as Attenborough’s definitive take on climate change. It followed a string of big budget, multipart wildlife documentaries, known in the industry as landmarks1, which broke with convention to incorporate narratives on complex environmental issues such as habitat destruction, species extinction and atmospheric pollution. David Attenborough’s The State of the Planet (2000), a smaller three-part series, was the first wildlife documentary to deal comprehensively with environmental issues on a global scale. -

How to Save the World STRATEGY for WORLD CONSERVATION

How to save the world STRATEGY FOR WORLD CONSERVATION Robert Allen AX Kogan Page IUCN UNEP WW This book is based on the World Conservation Strategy prepared by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), with the advice, cooperation and financial assistance of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Illustrations: Patrick Virolle Cartoons and cover design: Oliver Duke Copyright ; I UCN-UNEP-WWE 1980 All rights reserved First published 1980 by Kogan Page Limited 120 Pentonvitte Road London NI 9JN Printed in England by MCCorquodale (Newton) Ltd.. Newton-le-Willows, Lancashire. ISBN 0 85038 314 5 (Hb) iSBN (}85038 3153 (Pb) Contents Foreword 7 Preface 9 I. Why the world needs saving now and how it can be done 11 Securing the food supply 33 Forests: saving the saviours 53 Learning to live on planel sea 71 Coming to terms with our fellow species 93 Getting organized: a strategy for conservation 121 Implementing the strategy 145 Foreword Sir Peter Scott Chairman, World Wildlife Fund The World Conservation Strategy, on which this book is based, represents several firsts in nature conservation. it is the first time that governments, non-governmental organizations and experts throughout the world have been involved in preparing a global conservation document. it is the first time that it has been clearly shown how conservation can contribute to the development objectives of governments, industry, commerce, organized labour and the professions. And it is the first time that development has been suggested as a major means of achieving conservation, instead of being viewed as an obstruction to it. -

WORLD CONSERVATION STRATEGY Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development

WORLD CONSERVATION STRATEGY Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development Prepared by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) with the advice, cooperation and financial assistance of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and in collaboration with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (F AO) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) ~ '1 IUCN WWF The Symbol The circle symbolizes the biosphere-the thin covering of the planet that contains and sustains life. The three interlocking, overlapping arrows symbolize the three objectives of conservation: - maintenance of essential ecological processes and life-support systems; - preservation of genetic diversity; - sustainable utilization of species and ecosystems. WORLD CONSERVATION STRATEGY Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development Prepared by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) with the advice, cooperation and financial assistance of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and in collaboration with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (F AO) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) 1980 ~ ~ IUCN WWF The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, UNEP or WWF concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Copyright© IUCN-UNEP-WWF 1980 All rights reserved First published 1980 Second printing 1980 ISBN 2-88032-104-2 (Bound) ISBN 2-88032-101-8 (Pack) WORLD CONSERVATION STRATEGY Contents Preamble and Guide Foreword I Preface and acknowledgements ·II Guide to the World Conservation Strategy IV Executive Summary VI World Conservation Strategy 1. -

Sociality, Matter, and the Imagination: Re-Creating Anthropology Wolfson College Graduation-Cap Map of Venues and Accommodation

ASA18 Sociality, Matter, and the Imagination: Re-Creating Anthropology Wolfson College graduation-cap Map of Venues and Accommodation Lady Margaret Hall BED graduation-cap 58 Banbury Rd graduation-cap Keble College utensils Pitt Rivers Museum graduation-cap OU Museum of Natural History graduation-cap Queen Elizabeth House Balliol College BED Exeter College BED graduation-cap All Souls College Examination Schools graduation-cap graduation-cap BED Magdalen College St Hilda’s College BED wifi Wifi access at the venue Eduroam credentials can be used for accessing WiFi at the University of Oxford. Delegates can also request temporary credentials, for use during the conference, at the Reception desk when checking in. ASA18 Sociality, Matter, and the Imagination: Re-Creating Anthropology Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and Commonwealth Annual Conference University of Oxford 18-21 September 2018 ASA Committee: Chair: Professor Nigel Rapport (chair(at)theasa.org) Hon. secretary: Dr Cathrine Degnen (secretary(at)theasa.org) Hon. treasurer: Dr Soumhya Venkatesan (treasurer(at)theasa.org) ASA Committee members: Ethical guidelines: Dr Jude Robinson (ethics(at)theasa.org) ASA networks: Dr Julie Scott (networker(at)theasa.org) ASA series editor: Professor Andrew Irving (publications(at)theasa.org) Conference officer: Dr Emma Gilberthorpe (E.Gilberthorpe(at)uea.ac.uk) Media officer: Dr Paul GIlbert (media(at)theasa.org) Conference convenor: Prof David Gellner (Head of the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography at the University -

INTRODUCTION Drawn from Life: Mary Douglas's Personal Method

INTRODUCTION Drawn from life: Mary Douglas’s personal method Richard Fardon Mary Douglas (1921–2007) was the most widely read British anthropolo- gist of the second half of the twentieth century. Her writings continue to inspire researchers in numerous fields in the twenty-first century.1 This vol- ume of papers, first published over a period of almost fifty years, provides insights into the wellsprings of her style of thought and manner of writing. More popular counterparts to many of Douglas’s academic works – either the first formulation of an argument, or its more general statement – were often published around the same time as a specialist version. These first thoughts and popular re-imaginings are particularly revealing of the close relation between Douglas’s intellectual and personal concerns, a convergence that became more overt in her late career, when Mary Douglas occasionally wrote autobiographi- cally, explaining her ideas in relation to her upbringing, her family, and her experiences as both a committed Roman Catholic and a social anthropologist in the academy. The four social types of her theoretical writings – hierarchy, competition, the enclaved sect, and individuals in isolation – extend to remote times and distant places, prototypes that literally were close to home for her. This ability to expand and contract a restricted range of formal images allowed Mary Douglas to enter new fields of study with startling rapidity, to link unlikely domains of thought (through analogy, most frequently with religion), and to accommodate the most diverse examples in comparative frameworks. It was the way, to put it baldly, she made things fall into place. -

The German Exile Literature and the Early Novels of Iris Mur- Doch

University of Szeged Faculty of Arts Doctoral Dissertation The German Exile Literature and the Early Novels of Iris Mur- doch Dávid Sándor Szőke Supervisors: Dr. Zoltán Kelemen Dr. Anna Kérchy 2021 Acknowledgements I have a great number of people to thank for their support throughout this thesis, whether this support has been academic, financial, or spiritual. First of all, I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Zoltán Kelemen and Dr Anna Kérchy for their unending help, encouragement and faith in me during my research. Their knowledge about the Holocaust, 20th century English woman writers and minorities has given exceptional depth to my understanding of Murdoch, Steiner, Canetti and Adler. The eye-opening essays and lectures by Dr Peter Weber about the Romanian painter and Holocaust survivor Arnold Daghani’s time in England provided a genesis for this thesis. Had it not for him, I would not have thought about putting Murdoch’s thinking in the context of Cen- tral European refugee literature and culture during and after the Second World War. This thesis owes much to the 2017 Holocaust Conference in Szeged (19 October) and the 2019 International Holocaust Conference in Halle (14-16 November). I would like to express my gratitude to the March of the Living Hungary, the Holocaust Memorial Centre Budapest, the Memory Point of Hódmezővásárhely, the synagogues of Szeged and Hódmezővásárhely, Professor Werner Nell (Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg), Professor Thomas Bremer (Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg), Professor Sue Vice (University of Shef- field), and Dr Zoltán Kelemen for making these events possible. During my PhD, as part of the Erasmus ++ programme I spent an entire year at Martin- Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, where I made a great deal of research about the German coming to terms with the past. -

Gonzo Weekly #137

Subscribe to Gonzo Weekly http://eepurl.com/r-VTD Subscribe to Gonzo Daily http://eepurl.com/OvPez Gonzo Facebook Group https://www.facebook.com/groups/287744711294595/ Gonzo Weekly on Twitter https://twitter.com/gonzoweekly Gonzo Multimedia (UK) http://www.gonzomultimedia.co.uk/ Gonzo Multimedia (USA) http://www.gonzomultimedia.com/ 3 Princess Diana intensely, and encouraged the (probably apocryphal) story that a friend of mine queued for eleven hours in order to write surreal stoned drivel in the book of condolences in Exeter Cathedral. I also got sacked from my position at the BBC for claiming (on air) that her death had been the result of a conspiracy by Interflora, who seemed to have been the only people to benefit. Five years later when it all happened again I was less cynical, but refused to join in the grief for a lady of 101 to whom I was not related, despite the fact that she had lived an extraordinary life and achieved some extraordinary things. Over the lifespan (so far) of this magazine we have seen the deaths of many luminaries, and tried to celebrate their lives in these pages. Dear Friends, Two in particular Welcome to another issue of the best magazine in spring to the world put together for free by a bunch of social mind: Daevid outcasts, and edited by a fat bloke and his small Allen (earlier kitten. However, I think that last sentence qualifies this year) and it all a bit. Mick Farren (in 2013). I In 1999, and again in 2002, when much loved knew both public figures died, there was a great outpouring personally, of public grief, here in the UK at least, amongst and whilst large sectors of the population. -

Films and Videos on Tibet

FILMS AND VIDEOS ON TIBET Last updated: 15 July 2012 This list is maintained by A. Tom Grunfeld ( [email protected] ). It was begun many years ago (in the early 1990s?) by Sonam Dargyay and others have contributed since. I welcome - and encourage - any contributions of ideas, suggestions for changes, corrections and, of course, additions. All the information I have available to me is on this list so please do not ask if I have any additional information because I don't. I have seen only a few of the films on this list and, therefore, cannot vouch for everything that is said about them. Whenever possible I have listed the source of the information. I will update this list as I receive additional information so checking it periodically would be prudent. This list has no copyright; I gladly share it with whomever wants to use it. I would appreciate, however, an acknowledgment when the list, or any part, of it is used. The following represents a resource list of films and videos on Tibet. For more information about acquiring these films, contact the distributors directly. Office of Tibet, 241 E. 32nd Street, New York, NY 10016 (212-213-5010) Wisdom Films (Wisdom Publications no longer sells these films. If anyone knows the address of the company that now sells these films, or how to get in touch with them, I would appreciate it if you could let me know. Many, but not all, of their films are sold by Meridian Trust.) Meridian Trust, 330 Harrow Road, London W9 2HP (01-289-5443)http://www.meridian-trust/.org Mystic Fire Videos, P.O.