UNESCO- IUCN Enhancing Our Heritage Project: Monitoring and Managing for Success in Natural World Heritage Sites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation and the Impact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal Joanne Mclean Charles Sturt University (Australia)

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 19 Number 2 Himalayan Research Bulletin; Special Article 8 Topic: The Tharu 1999 Conservation and the Impact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal Joanne McLean Charles Sturt University (Australia) Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation McLean, Joanne (1999) "Conservation and the Impact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal," HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 19 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol19/iss2/8 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Conservation and the linpact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal Joanne McLean Charles Sturt University (Australia) Since the establishment of the first national park in the United States in the nineteenth century, indig enous peoples have been forced to move from regions designated as parks. Some of these people have been relocated to other areas by the government, more often they have been told to leave the area and are given no alternatives (Clay, 1985:2). Introduction (Guneratne 1994; Skar 1999). The Thant are often de scribed as one people. However, many subgroups exist: The relocation of indigenous people from national Kochjla Tharu in the eastern Tarai, Chitwaniya and Desauri parks has become standard practice in developing coun in the central Tarai, and Kathariya, Dangaura and Rana tries with little regard for the impacts it imposes on a Tharu in the western Tarai (Meyer & Deuel, 1999). -

Status and Effects of Food Provisioning on Ecology of Assamese Monkey (Macaca Assamensis) in Ramdi Area of Palpa, Nepal

STATUS AND EFFECTS OF FOOD PROVISIONING ON ECOLOGY OF ASSAMESE MONKEY (MACACA ASSAMENSIS) IN RAMDI AREA OF PALPA, NEPAL Krishna Adhikari, Laxman Khanal and Mukesh Kumar Chalise Journal of Institute of Science and Technology Volume 22, Issue 2, January 2018 ISSN: 2469-9062 (print), 2467-9240 (e) Editors: Prof. Dr. Kumar Sapkota Prof. Dr. Armila Rajbhandari Assoc. Prof. Dr. Gopi Chandra Kaphle Mrs. Reshma Tuladhar JIST, 22 (2): 183-190 (2018) Published by: Institute of Science and Technology Tribhuvan University Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal JIST 2018, 22 (2): 183-190 © IOST, Tribhuvan University ISSN: 2469-9062 (p), 2467-9240 (e) Research Article STATUS AND EFFECTS OF FOOD PROVISIONING ON ECOLOGY OF ASSAMESE MONKEY (MACACA ASSAMENSIS) IN RAMDI AREA OF PALPA, NEPAL Krishna Adhikari1, Laxman Khanal1, 2 and Mukesh Kumar Chalise1* 1Central Department of Zoology, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal 2Kunming Institute of Zoology, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Yunnan 650223, China *Corresponding E-mail: [email protected] Received: 3 October, 2017; Revised: 10 November, 2017; Accepted: 11 November, 2017 ABSTRACT The population status of Assamese monkey (Macaca assamensis) (McClelland 1840) and its interaction with the local people is poorly documented in Nepal. In 2014, we studied the population status, diurnal time budget and human-monkey conflict in Ramdi, Nepal by direct count, scan sampling and questionnaire survey methods, respectively. Two troops of Assamese monkey having total population of 48 with the mean troop size of 24 individuals were recorded in the study area. The group density was 0.33 groups / km² with a population density of 6 individuals/ km². The male to female adult sex ratio was 1:1.75 and the infant to female ratio was 0.85. -

Anthropogenic Impacts on Flora Biodiversity in the Forests and Common Land of Chitwan, Nepal

Anthropogenic impacts on flora biodiversity in the forests and common land of Chitwan, Nepal by Ganesh P. Shivakoti Co-Director Population and Ecology Research Laboratory Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science Tribhuvan University, Rampur, Nepal e-mail: [email protected] Stephen A. Matthews Research Associate Population Research Institute The Pennsylvania State University 601 Oswald Tower University Park, PA 18602-6211 e-mail: [email protected] and Netra Chhetri Graduate Student Department of Geography The Pennsylvania State University 302 Walker Building University Park, PA 16802 e-mail: [email protected] DRAFT COPY September 1997 Acknowledgment: This research was supported by two grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (Grant #R01-HD31982 and Grant #RO1-HD33551). We wish to thank William Axinn (PI on these grants), Dirgha Ghimire and the staff at the Population and Ecology Research Laboratory (PERL), IAAS, Nepal who helped collect the flora and common land data. Population growth and deforestation are serious problems in Chitwan and throughout Nepal. In this paper we explore the effect of social and demographic driving forces on flora diversity in Nepal. Specifically, we focus our attention on the flora diversity in three forested areas surrounding a recently deforested, settled and cultivated rural area - the Chitwan District. We have collected detailed counts of trees, shrubs, and grasses along the edge and in the interior of each forested area, and for common land throughout the settled area. Our sampling frame (described in the paper) allows us to construct detailed ordination and classification measures of forest floral diversity. Using techniques from quantitative ecology we can quantify species diversity (relative density, frequency and abundancy), and specifically measure the 'evenness' and 'richness' of the flora in the forested areas and common land. -

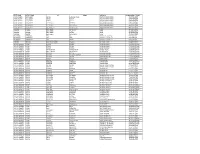

STATE NAME DISTRICT NAME GP Village CSP Name Contact Number Model Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Guthulavari Palem DURGA

STATE_NAME DISTRICT NAME GP Village CSP Name Contact number Model Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Guthulavari Palem DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Nemam DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Panduru Panduru DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Minorpeta DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Parrakalva DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Suryarao Peta DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Thimmapuram Thimmapuram DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek GADHI BESHAK asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek NAGLA PAR asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek NAGLAR asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek RAGA MAJRA asif ali 9991586053 EBT JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA Opa Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA JARIO Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA ROCHO Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI HARYANA BHIWANI VPOKAKROLI HUKMI Badhra KULWANT SINGH 8059809736 EBT HARYANA BHIWANI VPOKAKROLI HUKMI GOPI(35) KULWANT SINGH 8059809736 EBT MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON SEEGON ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON HANDIA ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON DHEDIYA ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA RAMTEKRAYYAT RAMTEK RAIYAT JAGDISH KALME 8120828495 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA RAMTEKRAYYAT -

Cases of Farmer Managed Irrigation Systems from East Chitwan'

Dynamics in Water Rights and Arbitration on Water Right Conflicts: Cases of Farmer Managed Irrigation Systems from East Chitwan' A. Shukla, N. R. Joshi, G. Shivakoti, R. Poudel and N. Shrestha' INTRODUCTION This paper examines the dynamism in water rights from the perspective of property creating process and its regulation and use and the mechanisms of arbitration when conflicts arise in the process. In conceptualizing irrigation development as property, the paper draws upon the property framework of Coward (1983). The development and subsequent management of irrigation systems involve investment of resources of some form, whether capital, labor, material or know- how. The mobilization and investment of resources may occur in private, community or state management regimes. Those who make the investment develop claims on the water supply that is acquired and the physical structures that are created for acquisition, conveyance, regulation and distribution of available supply of water. Even in the case of the state management, the investment of resources for imgation development has a targeted area and users to serve. Within the system each individual who has invested in the development and management of irrigation system has claim on the portion of available water supply. The collective claim on acquired supply of water is therefore apportioned into individual's claim. In defining the individual's claim the imgators come to a set of agreements that creates a social contract for 173 irrigators to realize their claims and acknowledge the claims of others. These agreements are apparent in the forms of rules, roles and sanctions to define, constrain and enforce individual’s claims (Pradhan 1987).While in some irrigation systems the set ofagreements are well articulated, in others there may be little codification. -

Proceedings of International Buffalo Symposium 2017 November 15-18 Chitwan, Nepal

“Enhancing Buffalo Production for Food and Economy” Proceedings of International Buffalo Symposium 2017 November 15-18 Chitwan, Nepal Faculty of Animal Science, Veterinary Science and Fisheries Agriculture and Forestry University Chitwan, Nepal Symposium Advisors: Prof. Ishwari Prasad Dhakal, PhD Vice Chancellor, Agriculture and Forestry University, Chitwan, Nepal Prof. Manaraj Kolachhapati, PhD Registrar, Agriculture and Forestry University, Chitwan, Nepal Baidhya Nath Mahato, PhD Executive Director, Nepal Agricultural Research Council, Nepal Dr. Bimal Kumar Nirmal Director General, Department of Livestock Services, Nepal Prof. Nanda P. Joshi, PhD Michigan State University, USA Director, Directorate of Research & Extension, Agriculture and Forestry Prof. Naba Raj Devkota, PhD University, Chitwan, Nepal Symposium Organizing Committee Logistic Sub-Committee Prof. Sharada Thapaliya, PhD Chair Prof. Ishwar Chandra Prakash Tiwari Coordinator Bhuminand Devkota, PhD Secretary Dr. Rebanta Kumar Bhattarai Member Prof. Ishwar Chandra Prakash Tiwari Member Prof. Mohan Prasad Gupta Member Prof. Mohan Sharma, PhD Member Matrika Jamarkatel Member Prof. Dr. Mohan Prasad Gupta Member Dr. Dipesh Kumar Chetri Member Hom Bahadur Basnet, PhD Member Dr. Anil Kumar Tiwari Member Matrika Jamarkatel Member Ram Krishna Pyakurel Member Dr. Subir Singh Member Communication/Mass Media Committee: Manoj Shah, PhD Member Ishwori Prasad Kadariya, PhD Coordinator Ishwori Prasad Kadariya, PhD Member Matrika Jamarkatel Member Rajendra Bashyal Member Nirajan Bhattarai, PhD Member Dr. Dipesh Kumar Chetri Member Himal Luitel, PhD Member Dr. Rebanta Kumar Bhattarai Member Nirajan Bhattarai, PhD Member Reception Sub-Committee Dr. Anjani Mishra Member Hom Bahadur Basnet, PhD Coordinator Gokarna Gautam, PhD Member Puskar Pal, PhD Member Himal Luitel, PhD Member Dr. Anil Kumar Tiwari Member Shanker Raj Barsila, PhD Member Dr. -

Impacts of Wildlife Tourism on Poaching of Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros Unicornis) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Impacts of Wildlife Tourism on Poaching of Greater One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Applied Science (Parks, Tourism and Ecology) at Lincoln University by Ana Nath Baral Lincoln University 2013 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Applied Science (Parks, Tourism and Ecology) Abstract Impacts of Wildlife Tourism on Poaching of Greater One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal by Ana Nath Baral Chitwan National Park (CNP) is one of the most important global destinations to view wildlife, particularly rhinoceros. The total number of wildlife tourists visiting the park has increased from 836 in Fiscal Year (FY) 1974/75 to 172,112 in FY 2011/12. But the rhinoceros, the main attraction for the tourists, is seriously threatened by poaching for its horn (CNP, 2012). Thus, the study of the relationship between wildlife tourism and rhinoceros poaching is essential for the management of tourism and control of the poaching. -

Historical Timeline of Hinduism in America 1780'S Trade Between

3/3/16, 11:23 AM Historical Timeline of Hinduism in America 1780's Trade between India and America. Trade started between India and America in the late 1700's. In 1784, a ship called "United States" arrived in Pondicherry. Its captain was Elias Hasket Derby of Salem. In the decades that followed Indian goods became available in Salem, Boston and Providence. A handful of Indian servant boys, perhaps the first Asian Indian residents, could be found in these towns, brought home by the sea captains.[1] 1801 First writings on Hinduism In 1801, New England writer Hannah Adams published A View of Religions, with a chapter discussing Hinduism. Joseph Priestly, founder of English Utilitarianism and isolater of oxygen, emigrated to America and published A Comparison of the Institutions of Moses with those of the Hindoos and other Ancient Nations in 1804. 1810-20 Unitarian interest in Hindu reform movements The American Unitarians became interested in Indian thought through the work of Hindu reformer Rammohun Roy (1772-1833) in India. Roy founded the Brahmo Samaj which tried to reform Hinduism by affirming monotheism and rejecting idolotry. The Brahmo Samaj with its universalist ideas became closely allied to the Unitarians in England and America. 1820-40 Emerson's discovery of India Ralph Waldo Emerson discovered Indian thought as an undergraduate at Harvard, in part through the Unitarian connection with Rammohun Roy. He wrote his poem "Indian Superstition" for the Harvard College Exhibition of April 24, 1821. In the 1830's, Emerson had copies of the Rig-Veda, the Upanishads, the Laws of Manu, the Bhagavata Purana, and his favorite Indian text the Bhagavad-Gita. -

Violation of Indigenous Peoples' Human Rights in Chitwan National Park of Nepal

Fact Finding Mission Report Violation of Indigenous Peoples' Human Rights in Chitwan National Park of Nepal Submitted to: Independent panel of experts-WWF Independent review Submitted by Lawyers’ Association for Human Rights of Nepalese IPs (LAHURNIP) National Indigenous Women Federation (NIWF) Anamnagar, Kathmandu, Nepal Post Box: 11179 Phone Number: +97715705510 Email:[email protected] February 2020 Researchers: Advocate, Shankar Limbu Expert (Applied Ecology, Engineer Ecologist), Yogeshwar Rai Chairperson (NIWF), Chinimaya Majhi Advocate, Dinesh Ghale Advocate, Amrita Thebe Indigenous Film Expert, Sanjog Lafa Magar Executive Summary Indigenous Peoples (IPs) of Nepal make up 9.54 million (36%) out of a total population of 26.5 million of the Country (Census 2011). The National Foundation for Development of Indigenous Nationalities (NFDIN) Act, 2002 recognizes and enlists 59 IPs or Indigenous Nationalities (Adibashi Janjati), with distinct cultures, traditions, beliefs system, social structure and history. At present, the Protected Areas (PAs) in Nepal include 12 National Parks, 1 Wildlife Reserve, 1 Hunting Reserve, 6 Conservation Areas and 13 BZs, covering over 3.4 million ha or 23.39% of the country. Most of the PAs are established in ancestral lands of IPs, displacing them and adversely impacting their existence, livelihoods, identity, and culture. They continue facing systematic discrimination as well as sexual offences against women, which qualifies as racism against IPs. This report is an outcome of a fact-finding mission looking into human rights violations as well as abuses in Chitwan National Park (CNP) of Nepal. The study enquires into, and traces recent reports by BuzzFeed, The Kathmandu Post and other media as well as reports which claim that the World Wide Fund for Nature Conservation (WWF) -one of conservation’s most famous organization-is responsible in many ways for torture, killings, sexual abuses as well as other gross human rights violations as part of their attempt to fight poaching. -

Schisms of Swami Muktananda's Siddha Yoga

Marburg Journal of Religion: Volume 15 (2010) Schisms of Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga John Paul Healy Abstract: Although Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga is a relatively new movement it has had a surprising amount of offshoots and schismatic groups claiming connection to its lineage. This paper discusses two schisms of Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga, Nityananda’s Shanti Mandir and Shankarananda’s Shiva Yoga. These are proposed as important schisms from Siddha Yoga because both swamis held senior positions in Muktananda’s original movement. The paper discusses the main episodes that appeared to cause the schism within Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga and the subsequent growth of Shanti Mandir and Shiva Yoga. Nityananda’s Shanti Mandir and Shankarananda’s Shiva Yoga may be considered as schisms developing from a leadership dispute rather than doctrinal differences. These groups may also present a challenge to Gurumayi’s Siddha Yoga as sole holder of the lineage of Swami Muktananda. Because of movements such as Shanti Mandir and Shiva Yoga, Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga Practice continues and grows, although, it is argued in this paper that it now grows through a variety of organisations. Introduction Prior to Swami Muktananda’s death in 1982 Swami Nityananda was named his successor to Siddha Yoga; by 1985 he was deposed by his sister and co-successor Gurumayi. Swami Shankarananda, a senior Swami in Siddha Yoga, sympathetic to Nityananda also left the movement around the same time. However, both swamis with the support of devotees of Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga, developed their own movements and today continue the lineage of their Guru and emphasise the importance of the Guru Disciple relationship within Swami Muktananda’s tradition. -

Nepal Biodiversity Strategy

NEPAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY His Majesty’s Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Supported by Global Environment Facility and UNDP 2002 : 2002, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, HMG, Nepal ISBN: 99933- xxx xxx Published by: His Majesty’s Government of Nepal Citation: HMGN/MFSC. 2002. Nepal Biodiversity Strategy, xxx pages Cover Photo: R.P. Chaudhary and King Mahendra Trust for Nature Conservation Back Photo: Nepal Tourism Board Acknowledgements The Nepal Biodiversity Strategy (NBS) is an important output of the Biodiversity Conservation Project of the Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation (MFSC) of His Majesty’s Government of Nepal. The Biodiversity Conservation Project is supported by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The preparation of the NBS is based on the substantial efforts of and assistance from numerous scientists, policy-makers and organisations who generously shared their data and expertise. The document represents the culmination of hard work by a broad range of government sectors, non- government organisations, and individual stakeholders. The MFSC would like to express sincere thanks to all those who contributed to this effort. The MFSC particularly recognises the fundamental contribution of Resources Nepal, under the leadership of Dr. P.B. Yonzon, for the extensive collection of data from various sources for the preparation of the first draft. The formulation of the strategy has been through several progressive drafts and rounds of consultations by representatives from Government, community-based organisations, NGOs, INGOs and donors. For the production of the second draft, the MFSC acknowledges the following: Prof. Ram P. -

Current Status of Asian Elephants in Nepal

Gajah 35 (2011) 87-92 Current Status of Asian Elephants in Nepal Narendra M. B. Pradhan1*, A. Christy Williams2 and Maheshwar Dhakal3 1WWF Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal 2WWF AREAS, Kathmandu, Nepal 3Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Kathmandu, Nepal *Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] Introduction Wild elephants Until the 1950s, much of the plains area of Population distribution southern Nepal known as the Terai was covered by forests uninhabited by humans due to malaria. Presently, the number of resident wild Asian It is believed that the elephants in these forests elephants in Nepal is estimated to be between 109 in Nepal and elephants in north and northeast and 142 animals (DNPWC 2008). They occur India constituted one contiguous population in four isolated populations (Eastern, Central, (DNPWC 2008). The eradication of malaria and Western and far-western). The area inhabited by government resettlement programs in the 1950s elephants is spread over 135 village development resulted in a rapid influx of people from the hills committees (VDC) in 19 districts (17 in lowland into the Terai. Besides, thousands of Nepalese Terai and 2 in the hills) of Nepal, covering about residing in Myanmar and India came back to 10,982 km2 of forest area (DNPWC 2008). Nepal due to the land reform program in the This widespread and fragmented distribution of 1960s (Kansakar 1979). The arrival of settlers elephants in the Terai underscores the importance meant the destruction of over 80% of the natural of the need for landscape level conservation habitat (Mishra 1980), which resulted in the planning as a strategy to protect elephants and fragmentation of wild elephants into partially or humans by maintaining forest corridors within completely isolated groups numbering less than the country (Fig.