Schisms of Swami Muktananda's Siddha Yoga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status and Effects of Food Provisioning on Ecology of Assamese Monkey (Macaca Assamensis) in Ramdi Area of Palpa, Nepal

STATUS AND EFFECTS OF FOOD PROVISIONING ON ECOLOGY OF ASSAMESE MONKEY (MACACA ASSAMENSIS) IN RAMDI AREA OF PALPA, NEPAL Krishna Adhikari, Laxman Khanal and Mukesh Kumar Chalise Journal of Institute of Science and Technology Volume 22, Issue 2, January 2018 ISSN: 2469-9062 (print), 2467-9240 (e) Editors: Prof. Dr. Kumar Sapkota Prof. Dr. Armila Rajbhandari Assoc. Prof. Dr. Gopi Chandra Kaphle Mrs. Reshma Tuladhar JIST, 22 (2): 183-190 (2018) Published by: Institute of Science and Technology Tribhuvan University Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal JIST 2018, 22 (2): 183-190 © IOST, Tribhuvan University ISSN: 2469-9062 (p), 2467-9240 (e) Research Article STATUS AND EFFECTS OF FOOD PROVISIONING ON ECOLOGY OF ASSAMESE MONKEY (MACACA ASSAMENSIS) IN RAMDI AREA OF PALPA, NEPAL Krishna Adhikari1, Laxman Khanal1, 2 and Mukesh Kumar Chalise1* 1Central Department of Zoology, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal 2Kunming Institute of Zoology, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Yunnan 650223, China *Corresponding E-mail: [email protected] Received: 3 October, 2017; Revised: 10 November, 2017; Accepted: 11 November, 2017 ABSTRACT The population status of Assamese monkey (Macaca assamensis) (McClelland 1840) and its interaction with the local people is poorly documented in Nepal. In 2014, we studied the population status, diurnal time budget and human-monkey conflict in Ramdi, Nepal by direct count, scan sampling and questionnaire survey methods, respectively. Two troops of Assamese monkey having total population of 48 with the mean troop size of 24 individuals were recorded in the study area. The group density was 0.33 groups / km² with a population density of 6 individuals/ km². The male to female adult sex ratio was 1:1.75 and the infant to female ratio was 0.85. -

The Malleability of Yoga: a Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 25 Article 4 November 2012 The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga Andrea R. Jain Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Jain, Andrea R. (2012) "The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 25, Article 4. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1510 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Jain: The Malleability of Yoga The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga Andrea R. Jain Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis FOR over three thousand years, people have yoga is Hindu. This assumption reflects an attached divergent meanings and functions to understanding of yoga as a homogenous system yoga. Its history has been characterized by that remains unchanged by its shifting spatial moments of continuity, but also by divergence and temporal contexts. It also depends on and change. This applies as much to pre- notions of Hindu authenticity, origins, and colonial yoga systems as to modern ones. All of even ownership. Both Hindu and Christian this evidences yoga’s malleability (literally, the opponents add that the majority of capacity to be bent into new shapes without contemporary yogis fail to recognize that yoga breaking) in the hands of human beings.1 is Hindu.3 Yet, today, a movement that assumes a Suspicious of decontextualized vision of yoga as a static, homogenous system understandings of yoga and, consequently, the rapidly gains momentum. -

Themelios an International Journal for Pastors and Students of Theological and Religious Studies

Themelios An International Journal for Pastors and Students of Theological and Religious Studies Volume 2 Issue 3 May, 1977 Contents Karl Barth and Christian apologetics Clark H Pinnock Five Ways to Salvation in Contemporary Guruism Vishal Mangalwadi The ‘rapture question’ Grant R Osborne Acts and Galatians reconsidered Colin J Hemer Book Reviews Vishal Mangalwadi, “Five Ways to Salvation in Contemporary Guruism,” Themelios 2.3 (May 1977): 72- 77. Five Ways to Salvation in Contemporary Guruism Vishal Mangalwadi [p.72] Man’s basic problem according to Hinduism is not moral but metaphysical. It is not that man is guilty of having broken God’s moral law, but that he has somehow forgotten his true nature and he experiences himself to be someone other than what he is. Man is not a sinner; he is simply ignorant of his true self. The problem is with his consciousness. His salvation consists in attaining that original state of consciousness which he has lost. Man’s true nature or original consciousness is defined differently by monistic and non-monistic gurus. The monistic gurus, who believe that God, man and the universe are ultimately one, teach that man is Infinite Consciousness or God, but has somehow been entangled in finite, personal, rational consciousness. So long as he remains in this state he is born repeatedly in this world of suffering. Salvation lies in transcending finite, personal consciousness and merging into (or experiencing ourselves to be) the Infinite Impersonal Consciousness, and thereby getting out of the cycle of births and deaths. In other words, salvation is a matter of perception or realization. -

History of Yoga 2

The History of Yoga by Christopher (Hareesh) Wallis (hareesh.org, mattamayura.org) 1. Yoga means joining oneself (yoga) firmly to a spiritual discipline (yoga), the central element of which is the process (yoga) of achieving integration (yoga) and full connection (yoga) to reality, primarily through scripturally prescribed exercises (yoga) characterized by the meta-principle of repeatedly bringing together all the energies of the body, mind, and senses in a single flow (ekāgratā) while maintaining tranquil focused presence (yukta, samāhita). 2. Yoga in the Indus Valley Civilization? 2500-1700 BCE [hardly likely!] 3. Yoga in the early Vedas? (lit., 'texts of knowledge,' 1800-800 BCE): not in the hymns (saṃhitās), but there are early yogic ideas in the priestly knowledge-books (brāhmaṇas and āraṇyakas) 4. Yoga in the śramana movement (600 – 300 BCE) A. the Buddha (Siddhārtha Gautama), 480 – 400 BCE B. Mahāvīra Jina, founder of Jainism, ca. 550 – 450 BCE 5. Yoga in the Upanishads (lit., 'hidden connections' 700 BCE -100 CE): key teachings A. "Thou art That" (tat tvam asi; Chāndogya Upanishad 6.8.7) • cf. "I am Brahman!" (aham brahmāsmi; Bṛhad-ārankaya Up. 1.4.10) • Practice (abhyāsa): SO’HAM japa B. "Two birds...nestle on the very same tree. One of them eats a tasty fig; the other, not eating, looks on." (Muṇḍaka Upanishad 3.1.1) • Practice: Witness Consciousness meditation C. "A divine Self (ātman) lies hidden in the heart of a living being...Regard that Self as God, an insight gained through inner contemplation." (Kaṭha Upanishad, ca. 200 BCE) • Practice: concentrative meditation. "When the five perceptions are stilled, when senses are firmly reined in, that is Yoga." • Practice: sense-withdrawal & one-pointedness D. -

Siddha Yoga Meditation Center in New York

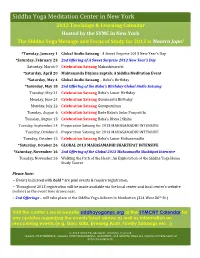

Siddha Yoga Meditation Center in New York 2013 Teachings & Learning Calendar Hosted by the SYMC in New York The Siddha Yoga Message and Focus of Study for 2013 is Mantra Japa! *Tuesday, January 1 Global Audio Satsang - A Sweet Surprise 2013 New Year’s Day *Saturday, February 23 2nd Offering of A Sweet Surprise 2013 New Year’s Day Saturday, March 9 Celebration Satsang Mahashivaratri *Saturday, April 20 Muktananda Dhyana Saptah: A Siddha Meditation Event *Saturday, May 4 Global Audio Satsang – Baba’s Birthday *Saturday, May 18 2nd Offering of the Baba’s Birthday Global Audio Satsang Tuesday, May 21 Celebration Satsang Baba’s Lunar Birthday Monday, June 24 Celebration Satsang Gurumayi’s Birthday Monday, July 22 Celebration Satsang Gurupurnima Tuesday, August 6 Celebration Satsang Bade Baba’s Solar Punyatithi Tuesday, August 13 Celebration Satsang Baba’s Divya Diksha Tuesday, September 24 Preparation Satsang for 2013 MAHASAMADHI INTENSIVE Tuesday, October 8 Preparation Satsang for 2013 MAHASAMADHI INTENSIVE Tuesday, October 15 Celebration Satsang Baba’s Lunar Mahasamadhi *Saturday, October 26 GLOBAL 2013 MAHASAMADHI SHAKTIPAT INTENSIVE *Saturday, November 16 2nd Offering of the Global 2013 Mahsamadhi Shaktipat Intensive Tuesday, November 26 Walking the Path of the Heart: An Exploration of the Siddha Yoga Home Study Course Please Note: ~ Events indicated with bold * are paid events & require registration. ~ Throughout 2013 registration will be made available via the local center and local center’s website (online) as the event time draws near. ~ 2nd Offerings – will take place at the Siddha Yoga Ashram in Manhattan (324 West 86th St.) Visit the center’s local website siddhayoganyc.org or the SYMCNY Calendar for any updates regarding the events listed above as well as information on reoccurring events (e.g. -

STATE NAME DISTRICT NAME GP Village CSP Name Contact Number Model Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Guthulavari Palem DURGA

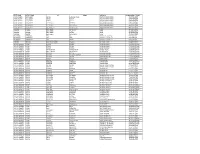

STATE_NAME DISTRICT NAME GP Village CSP Name Contact number Model Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Guthulavari Palem DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Nemam DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Panduru Panduru DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Minorpeta DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Parrakalva DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Suryarao Peta DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Thimmapuram Thimmapuram DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek GADHI BESHAK asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek NAGLA PAR asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek NAGLAR asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek RAGA MAJRA asif ali 9991586053 EBT JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA Opa Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA JARIO Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA ROCHO Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI HARYANA BHIWANI VPOKAKROLI HUKMI Badhra KULWANT SINGH 8059809736 EBT HARYANA BHIWANI VPOKAKROLI HUKMI GOPI(35) KULWANT SINGH 8059809736 EBT MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON SEEGON ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON HANDIA ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON DHEDIYA ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA RAMTEKRAYYAT RAMTEK RAIYAT JAGDISH KALME 8120828495 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA RAMTEKRAYYAT -

Branding Yoga the Cases of Iyengar Yoga, Siddha Yoga and Anusara Yoga

ANDREA R. JAIN Branding yoga The cases of Iyengar Yoga, Siddha Yoga and Anusara Yoga n October 1989, long-time yoga student, John Friend modern soteriological yoga system based on ideas and (b. 1959) travelled to India to study with yoga mas- practices primarily derived from tantra. The encounter Iters. First, he went to Pune for a one-month intensive profoundly transformed Friend, and Chidvilasananda in- postural yoga programme at the Ramamani Iyengar itiated him into Siddha Yoga (Williamson forthcoming). Memor ial Yoga Institute, founded by a world-famous yoga proponent, B. K. S. Iyengar (b. 1918). Postural yoga (De Michelis 2005, Singleton 2010) refers to mod- Friend spent the next seven years deepening his ern biomechanical systems of yoga, which are based understanding of both Iyengar Yoga and Siddha Yoga. on sequences of asana or postures that are, through He gained two Iyengar Yoga teaching certificates and pranayama or ‘breathing exercises’, synchronized with taught Iyengar Yoga in Houston, Texas. Every sum- 1 the breath. Following Friend’s training in Iyengar Yoga, mer, he travelled to Siddha Yoga’s Shree Muktananda he travelled to Ganeshpuri, India where he met Chid- Ashram in upstate New York, where he would study 1954 vilasananda (b. ), the current guru of Siddha Yoga, for one to three months at a time. at the Gurudev Siddha Peeth ashram.2 Siddha Yoga is a Friend founded his own postural yoga system, Anusara Yoga, in 1997 in The Woodlands, a high- 1 Focusing on English-speaking milieus beginning in end Houston suburb. Anusara Yoga quickly became the 1950s, Elizabeth De Michelis categorizes modern one of the most popular yoga systems in the world. -

The Siddha-Yoga to the Test of the Criticism

1 The Siddha-Yoga to the test of the criticism. by Bruno Delorme - April 2018 - Presentation: This reflection is the culmination of a project that has been close to my heart for a long time: to write about an Indian sect, Siddha-Yoga, to which I belonged in my late teens. It presents itself at the same time as a historical, sociological, and psychoanalytic analysis. I wanted to put at the beginning my personal testimony which opens the reflection, and this in order to show how this movement affected me at a certain period of my life, and what it also produced in me. A Summary at the end of the article allows you to identify the main chapters. 2 My passage in the movement of Siddha-Yoga. Testimony by Bruno Delorme1 It was during the year 1978, when I was starting my professional life and after repeated school failures, that I became acquainted with Siddha-Yoga. My best friend at the time was involved in it and so talked to me about it at length. We were both in search of meaning in our lives and in search of spirituality. And Siddha-Yoga suddenly seemed to offer us what we had been looking for a long time. I joined the movement a year after him, and I discovered it through two communities that were roughly equidistant from the city where I lived: the Dijon ashram and the Lyon ashram. The latter was headed by A. C. and his wife, better known today for having managed the association "Terre du Ciel" and its magazine. -

A Short Description of Maha Yoga

A Short Description of Maha Yoga The Simple, Easy and Free Path to Self-Realization What is Maha Yoga? All human beings have three distinct elements – body, mind and spirit. All of us are aware of our bodies, and most of us are aware of our minds. However, far too many of us are unaware of the spirit that resides in each one of us. Our normal awareness often extends only to our bodies and to our minds. Only rarely do some of us get the experience of being actually aware of our own spiritual existence. The objective of Yoga is to extend our Awareness beyond our bodies and our minds to the spirit (Prana), the Universal Life Energy (Chaitanya Shakti) that lies dormant in each and every one of us. When our Awareness merges with the Chaitanya we get happiness and satisfaction in all aspects of our lives, eventually leading to eternal bliss. This union of our Awareness with the Chaitanya is the true meaning of the term Yoga, which means “union” in Sanskrit. The dormant sliver of Chaitanya Shakti, which resides in all of us, is referred to in Yoga terminology as the Kundalini Shakti (Kundalini Energy). Since our brains are usually chockfull of the physical and mental clutter of our day-to-day lives, the Kundalini in most of us gets pushed to the opposite end of our nervous system, the base of our spine (Mooladhara Chakra). There it lies dormant in its subtle form leaving most of us completely unaware of its existence throughout our lives. -

Historical Timeline of Hinduism in America 1780'S Trade Between

3/3/16, 11:23 AM Historical Timeline of Hinduism in America 1780's Trade between India and America. Trade started between India and America in the late 1700's. In 1784, a ship called "United States" arrived in Pondicherry. Its captain was Elias Hasket Derby of Salem. In the decades that followed Indian goods became available in Salem, Boston and Providence. A handful of Indian servant boys, perhaps the first Asian Indian residents, could be found in these towns, brought home by the sea captains.[1] 1801 First writings on Hinduism In 1801, New England writer Hannah Adams published A View of Religions, with a chapter discussing Hinduism. Joseph Priestly, founder of English Utilitarianism and isolater of oxygen, emigrated to America and published A Comparison of the Institutions of Moses with those of the Hindoos and other Ancient Nations in 1804. 1810-20 Unitarian interest in Hindu reform movements The American Unitarians became interested in Indian thought through the work of Hindu reformer Rammohun Roy (1772-1833) in India. Roy founded the Brahmo Samaj which tried to reform Hinduism by affirming monotheism and rejecting idolotry. The Brahmo Samaj with its universalist ideas became closely allied to the Unitarians in England and America. 1820-40 Emerson's discovery of India Ralph Waldo Emerson discovered Indian thought as an undergraduate at Harvard, in part through the Unitarian connection with Rammohun Roy. He wrote his poem "Indian Superstition" for the Harvard College Exhibition of April 24, 1821. In the 1830's, Emerson had copies of the Rig-Veda, the Upanishads, the Laws of Manu, the Bhagavata Purana, and his favorite Indian text the Bhagavad-Gita. -

V Edictradition S Hramanatradition

V e d i c t r a d i t i o n S h r a m a n a t r a d i t i o n Samkhya Buddhism ―Brahmanas‖ 900-500 T a n t r a BCE Jainism ―Katha ―Bhagavad Upanishad‖ Gita‖ 6th Century 5th—2nd BCE ―Samkhya Century BCE Karika‖ Patnanjali’s Yogachara ―Tattvarthasutra‖ Buddhism 200 CE ―Sutras‖ 2nd Century CE Adi Nanth 4th –5th (Shiva?) 100 BCE-500CE Century CE The Naths Matsyendranath ―Hatha Yoga‖ Raja ―Lord of Fish‖ (Classical) Yoga Helena Guru Nanak Dev Ji Gorakshanath Blavatsky ―Sikhism‖ ―Laya Yoga‖ b. 8th century 15th Century ―Theosophists‖ “Hatha Yoga Pradipika” Annie by Yogi Swatmarama Besant 16th Centruy Charles Leadbeater ―The Serpent Power‖ Krishnanand Babu Saraswati Bhagwan Das British John Woodroffe Mahavatar Babaji Gymnastics (Arthur Avalon) (Saint?) Late 19th/early 20th century Bhagavan Ramakrishna Vivekananda ―Kriya Yoga‖ Nitkananda Vishnu Vishwananda B. 1888 b. 1863 Yoga ―Krama Vinyasa‖ Bhaskar Lele Saraswati Kurunta Dadaji Ramaswami Lahiri Mahasaya Brahmananda ―World’s ―Siddha Paliament on Yoga‖ Saraswati Bengali Mahapurush Religion‖ B. 1870 Maharaj ―Integral Yoga‖ Baba Muktananda Krishnamurti B. 1908 A.G. Krishnamacharya B. 1895 Sri Sivananda Yukteswar Giri Nirmalanda Auribindo Mirra Ghandi Mohan B. 1888 B. 1872 Alfassa B. 1887 ―Transcendental Swami ―Kundalini ―Divine Meditation‖ Chidvilasananda Kailashananda Indra Yoga‖ 1935 Life Desikachar Devi Swami Society‖ Yogananda Maharishi (son) Kripalvananda Sri Mahesh Yogi Auribindo b. 1893 ―viniyoga‖ b. 1913 Asharam Bishnu Ghosh ―Ashtanga Yogi ―Autobiography Dharma Mittra Gary Yoga‖ ―Light of a Yogi‖ (brother) Mahamandaleshwar Kraftsow BKS on Bhajan Nityandanda b. 1939 Patabhi Jois Iyengar Yoga‖ b. -

Aghoreshwar Bhagawan Ram and the Aghor Tradition

Syracuse University SURFACE Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Anthropology - Dissertations Affairs 12-2011 Aghoreshwar Bhagawan Ram and the Aghor Tradition Jishnu Shankar Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/ant_etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Shankar, Jishnu, "Aghoreshwar Bhagawan Ram and the Aghor Tradition" (2011). Anthropology - Dissertations. 93. https://surface.syr.edu/ant_etd/93 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Aghoreshwar Mahaprabhu Baba Bhagawan Ram Ji, a well-established saint of the holy city of Varanasi in north India, initiated many changes into the erstwhile Aghor tradition of ascetics in India. This tradition is regarded as an ancient system of spiritual or mystical knowledge by its practitioners and at least some of the practices followed in this tradition can certainly be traced back at least to the time of the Buddha. Over the course of the centuries practitioners of this tradition have interacted with groups of other mystical traditions, exchanging ideas and practices so that both parties in the exchange appear to have been influenced by the other. Naturally, such an interaction between groups can lead to difficulty in determining a clear course of development of the tradition. In this dissertation I bring together micro-history, hagiography, folklore, religious and comparative studies together in an attempt to understand how this modern day religious-spiritual tradition has been shaped by the past and the role religion has to play in modern life, if only with reference to a single case study.