The Siddha-Yoga to the Test of the Criticism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Malleability of Yoga: a Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 25 Article 4 November 2012 The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga Andrea R. Jain Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Jain, Andrea R. (2012) "The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 25, Article 4. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1510 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Jain: The Malleability of Yoga The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga Andrea R. Jain Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis FOR over three thousand years, people have yoga is Hindu. This assumption reflects an attached divergent meanings and functions to understanding of yoga as a homogenous system yoga. Its history has been characterized by that remains unchanged by its shifting spatial moments of continuity, but also by divergence and temporal contexts. It also depends on and change. This applies as much to pre- notions of Hindu authenticity, origins, and colonial yoga systems as to modern ones. All of even ownership. Both Hindu and Christian this evidences yoga’s malleability (literally, the opponents add that the majority of capacity to be bent into new shapes without contemporary yogis fail to recognize that yoga breaking) in the hands of human beings.1 is Hindu.3 Yet, today, a movement that assumes a Suspicious of decontextualized vision of yoga as a static, homogenous system understandings of yoga and, consequently, the rapidly gains momentum. -

Themelios an International Journal for Pastors and Students of Theological and Religious Studies

Themelios An International Journal for Pastors and Students of Theological and Religious Studies Volume 2 Issue 3 May, 1977 Contents Karl Barth and Christian apologetics Clark H Pinnock Five Ways to Salvation in Contemporary Guruism Vishal Mangalwadi The ‘rapture question’ Grant R Osborne Acts and Galatians reconsidered Colin J Hemer Book Reviews Vishal Mangalwadi, “Five Ways to Salvation in Contemporary Guruism,” Themelios 2.3 (May 1977): 72- 77. Five Ways to Salvation in Contemporary Guruism Vishal Mangalwadi [p.72] Man’s basic problem according to Hinduism is not moral but metaphysical. It is not that man is guilty of having broken God’s moral law, but that he has somehow forgotten his true nature and he experiences himself to be someone other than what he is. Man is not a sinner; he is simply ignorant of his true self. The problem is with his consciousness. His salvation consists in attaining that original state of consciousness which he has lost. Man’s true nature or original consciousness is defined differently by monistic and non-monistic gurus. The monistic gurus, who believe that God, man and the universe are ultimately one, teach that man is Infinite Consciousness or God, but has somehow been entangled in finite, personal, rational consciousness. So long as he remains in this state he is born repeatedly in this world of suffering. Salvation lies in transcending finite, personal consciousness and merging into (or experiencing ourselves to be) the Infinite Impersonal Consciousness, and thereby getting out of the cycle of births and deaths. In other words, salvation is a matter of perception or realization. -

History of Yoga 2

The History of Yoga by Christopher (Hareesh) Wallis (hareesh.org, mattamayura.org) 1. Yoga means joining oneself (yoga) firmly to a spiritual discipline (yoga), the central element of which is the process (yoga) of achieving integration (yoga) and full connection (yoga) to reality, primarily through scripturally prescribed exercises (yoga) characterized by the meta-principle of repeatedly bringing together all the energies of the body, mind, and senses in a single flow (ekāgratā) while maintaining tranquil focused presence (yukta, samāhita). 2. Yoga in the Indus Valley Civilization? 2500-1700 BCE [hardly likely!] 3. Yoga in the early Vedas? (lit., 'texts of knowledge,' 1800-800 BCE): not in the hymns (saṃhitās), but there are early yogic ideas in the priestly knowledge-books (brāhmaṇas and āraṇyakas) 4. Yoga in the śramana movement (600 – 300 BCE) A. the Buddha (Siddhārtha Gautama), 480 – 400 BCE B. Mahāvīra Jina, founder of Jainism, ca. 550 – 450 BCE 5. Yoga in the Upanishads (lit., 'hidden connections' 700 BCE -100 CE): key teachings A. "Thou art That" (tat tvam asi; Chāndogya Upanishad 6.8.7) • cf. "I am Brahman!" (aham brahmāsmi; Bṛhad-ārankaya Up. 1.4.10) • Practice (abhyāsa): SO’HAM japa B. "Two birds...nestle on the very same tree. One of them eats a tasty fig; the other, not eating, looks on." (Muṇḍaka Upanishad 3.1.1) • Practice: Witness Consciousness meditation C. "A divine Self (ātman) lies hidden in the heart of a living being...Regard that Self as God, an insight gained through inner contemplation." (Kaṭha Upanishad, ca. 200 BCE) • Practice: concentrative meditation. "When the five perceptions are stilled, when senses are firmly reined in, that is Yoga." • Practice: sense-withdrawal & one-pointedness D. -

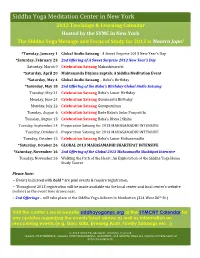

Siddha Yoga Meditation Center in New York

Siddha Yoga Meditation Center in New York 2013 Teachings & Learning Calendar Hosted by the SYMC in New York The Siddha Yoga Message and Focus of Study for 2013 is Mantra Japa! *Tuesday, January 1 Global Audio Satsang - A Sweet Surprise 2013 New Year’s Day *Saturday, February 23 2nd Offering of A Sweet Surprise 2013 New Year’s Day Saturday, March 9 Celebration Satsang Mahashivaratri *Saturday, April 20 Muktananda Dhyana Saptah: A Siddha Meditation Event *Saturday, May 4 Global Audio Satsang – Baba’s Birthday *Saturday, May 18 2nd Offering of the Baba’s Birthday Global Audio Satsang Tuesday, May 21 Celebration Satsang Baba’s Lunar Birthday Monday, June 24 Celebration Satsang Gurumayi’s Birthday Monday, July 22 Celebration Satsang Gurupurnima Tuesday, August 6 Celebration Satsang Bade Baba’s Solar Punyatithi Tuesday, August 13 Celebration Satsang Baba’s Divya Diksha Tuesday, September 24 Preparation Satsang for 2013 MAHASAMADHI INTENSIVE Tuesday, October 8 Preparation Satsang for 2013 MAHASAMADHI INTENSIVE Tuesday, October 15 Celebration Satsang Baba’s Lunar Mahasamadhi *Saturday, October 26 GLOBAL 2013 MAHASAMADHI SHAKTIPAT INTENSIVE *Saturday, November 16 2nd Offering of the Global 2013 Mahsamadhi Shaktipat Intensive Tuesday, November 26 Walking the Path of the Heart: An Exploration of the Siddha Yoga Home Study Course Please Note: ~ Events indicated with bold * are paid events & require registration. ~ Throughout 2013 registration will be made available via the local center and local center’s website (online) as the event time draws near. ~ 2nd Offerings – will take place at the Siddha Yoga Ashram in Manhattan (324 West 86th St.) Visit the center’s local website siddhayoganyc.org or the SYMCNY Calendar for any updates regarding the events listed above as well as information on reoccurring events (e.g. -

Branding Yoga the Cases of Iyengar Yoga, Siddha Yoga and Anusara Yoga

ANDREA R. JAIN Branding yoga The cases of Iyengar Yoga, Siddha Yoga and Anusara Yoga n October 1989, long-time yoga student, John Friend modern soteriological yoga system based on ideas and (b. 1959) travelled to India to study with yoga mas- practices primarily derived from tantra. The encounter Iters. First, he went to Pune for a one-month intensive profoundly transformed Friend, and Chidvilasananda in- postural yoga programme at the Ramamani Iyengar itiated him into Siddha Yoga (Williamson forthcoming). Memor ial Yoga Institute, founded by a world-famous yoga proponent, B. K. S. Iyengar (b. 1918). Postural yoga (De Michelis 2005, Singleton 2010) refers to mod- Friend spent the next seven years deepening his ern biomechanical systems of yoga, which are based understanding of both Iyengar Yoga and Siddha Yoga. on sequences of asana or postures that are, through He gained two Iyengar Yoga teaching certificates and pranayama or ‘breathing exercises’, synchronized with taught Iyengar Yoga in Houston, Texas. Every sum- 1 the breath. Following Friend’s training in Iyengar Yoga, mer, he travelled to Siddha Yoga’s Shree Muktananda he travelled to Ganeshpuri, India where he met Chid- Ashram in upstate New York, where he would study 1954 vilasananda (b. ), the current guru of Siddha Yoga, for one to three months at a time. at the Gurudev Siddha Peeth ashram.2 Siddha Yoga is a Friend founded his own postural yoga system, Anusara Yoga, in 1997 in The Woodlands, a high- 1 Focusing on English-speaking milieus beginning in end Houston suburb. Anusara Yoga quickly became the 1950s, Elizabeth De Michelis categorizes modern one of the most popular yoga systems in the world. -

A Short Description of Maha Yoga

A Short Description of Maha Yoga The Simple, Easy and Free Path to Self-Realization What is Maha Yoga? All human beings have three distinct elements – body, mind and spirit. All of us are aware of our bodies, and most of us are aware of our minds. However, far too many of us are unaware of the spirit that resides in each one of us. Our normal awareness often extends only to our bodies and to our minds. Only rarely do some of us get the experience of being actually aware of our own spiritual existence. The objective of Yoga is to extend our Awareness beyond our bodies and our minds to the spirit (Prana), the Universal Life Energy (Chaitanya Shakti) that lies dormant in each and every one of us. When our Awareness merges with the Chaitanya we get happiness and satisfaction in all aspects of our lives, eventually leading to eternal bliss. This union of our Awareness with the Chaitanya is the true meaning of the term Yoga, which means “union” in Sanskrit. The dormant sliver of Chaitanya Shakti, which resides in all of us, is referred to in Yoga terminology as the Kundalini Shakti (Kundalini Energy). Since our brains are usually chockfull of the physical and mental clutter of our day-to-day lives, the Kundalini in most of us gets pushed to the opposite end of our nervous system, the base of our spine (Mooladhara Chakra). There it lies dormant in its subtle form leaving most of us completely unaware of its existence throughout our lives. -

Schisms of Swami Muktananda's Siddha Yoga

Marburg Journal of Religion: Volume 15 (2010) Schisms of Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga John Paul Healy Abstract: Although Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga is a relatively new movement it has had a surprising amount of offshoots and schismatic groups claiming connection to its lineage. This paper discusses two schisms of Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga, Nityananda’s Shanti Mandir and Shankarananda’s Shiva Yoga. These are proposed as important schisms from Siddha Yoga because both swamis held senior positions in Muktananda’s original movement. The paper discusses the main episodes that appeared to cause the schism within Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga and the subsequent growth of Shanti Mandir and Shiva Yoga. Nityananda’s Shanti Mandir and Shankarananda’s Shiva Yoga may be considered as schisms developing from a leadership dispute rather than doctrinal differences. These groups may also present a challenge to Gurumayi’s Siddha Yoga as sole holder of the lineage of Swami Muktananda. Because of movements such as Shanti Mandir and Shiva Yoga, Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga Practice continues and grows, although, it is argued in this paper that it now grows through a variety of organisations. Introduction Prior to Swami Muktananda’s death in 1982 Swami Nityananda was named his successor to Siddha Yoga; by 1985 he was deposed by his sister and co-successor Gurumayi. Swami Shankarananda, a senior Swami in Siddha Yoga, sympathetic to Nityananda also left the movement around the same time. However, both swamis with the support of devotees of Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga, developed their own movements and today continue the lineage of their Guru and emphasise the importance of the Guru Disciple relationship within Swami Muktananda’s tradition. -

Routledge Handbook of Yoga and Meditation Studies

iii ROUTLEDGE HANDBOOK OF YOGA AND MEDITATION STUDIES Edited by Suzanne Newcombe and Karen O’Brien- Kop First published 2021 ISBN: 978- 1- 138- 48486- 3 (hbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 351- 05075- 3 (ebk) 27 OBSERVING YOGA The use of ethnography to develop yoga studies Daniela Bevilacqua (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 647963 (Hatha Yoga Project)). 393 2 7 OBSERVING YOGA 1 Th e use of ethnography to develop yoga studies D a n i e l a B e v i l a c q u a Introduction Ethnography as a method can be defi ned as an approach to social research based on fi rst- hand experience. As a methodology, it intends to create an epistemology that emphasises the signifi - cance and meaning of the experiences of the group of people being studied, thereby privileging the insider’s view. A researcher using ethnography employs mostly qualitative methods (Pole and Morrison 2003: 9), such as interviews (that can be non- structured, structured or casual con- versation), participant observation, fi eld notes, etc. Participant observation can be considered as a distinctive feature of ethnography; within this method the researcher adopts a variety of positions. As Atkinson and Hammersley have noted ( 1994 : 248), the researcher can be: a complete observer when the researcher is a member of the group being studied who conceals his/ her researcher role; an observer as participant when s/ he is a member of the group being studied and the group is aware of the research activity; a participant as observer when s/ he is not a member of the group but is interested in par- ticipating as a means for conducting better observation; or a participant non-member of the group who is hidden from view while observing. -

Kundalini and the Complete Maturation of the Ensouled Body

KUNDALINI AND THE COMPLETE MATURATION OF THE ENSOULED BODY Stuart Sovatsky, Ph.D. Richmond, California ABSTRACT: In utero and infantile developmental manifestations of kundalini, the ‘‘ultimate maturational force’’ according to yogic traditions, are traced to numerous advanced yogic processes, including urdhva-retas (lifelong neuroendocrine maturation), khecari mudra (puberty-like maturation of the tongue, hypothalamus and pineal) and sahaja asanas (spontaneously arising yoga asanas) and their cross-cultural cognates that, altogether, form the somatic basis for all manner of spiritual aspirations and complete maturation of the ensouled body. At the collective level and according to the centermost Vedic maxim, Vasudhaiva kutumbakam (The world is one family), a vast majority of successful fifty-year marriages interspersed with sannyasins (fulltime yogis) indicates a spiritually matured society. Thus, along with developing spiritual emergence counseling techniques for individuals in spiritual crises, transpersonal clinicians might draw from ashrama and tantric mappings of lifelong developmental stages to support marriages, families and communities and thus, over future centuries, reverse current familial/global brokenness and foster the emergence of mature, enlightened, whole cultures. A coil of lightning, a flame of fire folded (224) She [kundalini] cleans the skin down to the skeleton (233) Old age gets reversed (260) She…dissolves the five [bodily] elements (291) …[then] the yogi is known as Khecar [tumescent tongued] Attaining this state -

Kundalini and Siddha Yoga

Kundalini and Siddha Yoga Kundalini and Siddha Yoga Personal Story by "Erosion" I had a kundalini awakening March 15 1994, living in a small rural city in Alaska USA I am now 49 years old woman and I live in Oregon in the United States. My situation was that I was very ignorant on what happened to me, I'm not sure even where to start. I was reading new age books about seeking the self within our selves for about 5 years before this date, but I was not practising any yoga of any kind. I was introduced to Yoga called Siddha Yoga by a friend and I had a vision of a Guru named Swami Chidvilasananda or better known as Gurumayi the Guru of Siddha Yoga. She appeared before me in a dream and let me ask her questions, she was very sweet and quiet and I woke up from the dream puzzled. I now understand this was darshan of a Guruwhere I received initiation. I didn't know this at the time, I knew nothing of Yoga or Siddha yoga. Except for some Hatha Yoga classes I took in college. Anyway I borrowed a book of my friends called The Play of Consciousness by Swami Muktananda and read this book three times in a row trying to understand what it was saying and I had a Kundalini awakening. It was very intense, but from reading this book I understood that it was a safe process. Now at this point in my life I was living in Alaska and my only contact to this Yoga was my friend and a book, and that dream. -

Making Waves

INTRODUCTION MAKING WAVES THOMAS A. FORSTHOEFEL AND CYNTHIA ANN HUMES EVERYTHING CHANGES. Mystics and storytellers in South Asia have woven this deceptively simple observation into the Indic consciousness for millennia. Hindu scriptures warn that the true nature of endlessly changing phenomenal reality can be lost to us as we thrash about the crashing waves of life.Yet the Hindu emphasis on the phenomenal fact of impermanence is tempered by the promise of something substantial, enduring, and utterly liberating beyond the very flux of life, so often likened to a roiling ocean, the “ocean of samsara.”The phenomenal flux of mundane reality, staggering in its chaos and suffering, nonetheless motivates the journey to cross the “far shore,” the quintessential Indian metaphor for lib- eration. Among the premier rafts for this tumultuous crossing is the spiritual teacher, the guru, a term that, not incidentally, also means “heavy.”The word intimates the higher truth that there is something weighty, substantial, and enduring about life, a truth borne witness to by extraordinary spiritual teach- ers. Gurus assist in the journey to make the crossing—from the ocean of sam- sara to the ocean of awareness, from the changing flux of phenomenal reality to the far shore of liberation, from death to immortality.The far shore is the “site” for an ultimate ground that suffers no loss or change, understood vari- ously in Hinduism to be an enduring soul, consciousness, an unchanging Absolute or a deity with form. This book is about gurus who have crossed the far shore, but not necessar- ily to ultimate liberation. -

Non-Postural Yoga(S), Embodiment and Spiritual Capital

Article Serving, Contemplating and Praying: Non-Postural Yoga(s), Embodiment and Spiritual Capital Matteo Di Placido Department of Sociology and Social Research, University of Milan-Bicocca, 20126 Milan, Italy; [email protected] Received: 9 July 2018; Accepted: 6 September 2018; Published: 9 September 2018 Abstract: In this paper, I discuss the role of spiritual seekers’ embodiment of karma, jnana and bhakti yoga(s) in the context of a neo-Vedantic, non-monastic ashram located in southern-Europe, an ashram I regard as an example of modern denominational yoga. Methodologically, I rely on an ex-post multi-sensory autoethnography, involving apprenticeship and full participation immersion, and I share with physical cultural studies a commitment to empirically contextualise the study of the moving body. Theoretically, I employ Shilling’s theory of the body as a multi-dimensional medium for the constitution of society, enriched by other theoretical and sensitising concepts. The findings presented in this paper show that the body of the seekers/devotees can be simultaneously framed as the source of, the location for and the means to, the constitution of the social, cultural and spiritual life of the ashram. As I discuss the development, interiorisation and implementation of serving, contemplative and devotional dispositions, which together form the scheme of dispositions that shape a yogic habitus, I also consider the ties between the specific instances under study and the more general spiritual habitus. The paper ends by broadening its focus in relation to the inclusion of Asian practices and traditions into the Western landscape. Keywords: karma yoga; jnana yoga; bhakti yoga; modern denominational yoga; body; physical culture(s); multi-sensory autoethnography; apprenticeship; full participation; neo-Vedanta 1.