Status and Effects of Food Provisioning on Ecology of Assamese Monkey (Macaca Assamensis) in Ramdi Area of Palpa, Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STATE NAME DISTRICT NAME GP Village CSP Name Contact Number Model Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Guthulavari Palem DURGA

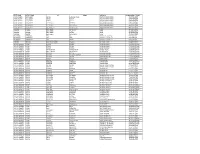

STATE_NAME DISTRICT NAME GP Village CSP Name Contact number Model Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Guthulavari Palem DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Nemam DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Panduru Panduru DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Minorpeta DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Parrakalva DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Suryarao Peta DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Thimmapuram Thimmapuram DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek GADHI BESHAK asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek NAGLA PAR asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek NAGLAR asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek RAGA MAJRA asif ali 9991586053 EBT JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA Opa Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA JARIO Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA ROCHO Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI HARYANA BHIWANI VPOKAKROLI HUKMI Badhra KULWANT SINGH 8059809736 EBT HARYANA BHIWANI VPOKAKROLI HUKMI GOPI(35) KULWANT SINGH 8059809736 EBT MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON SEEGON ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON HANDIA ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON DHEDIYA ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA RAMTEKRAYYAT RAMTEK RAIYAT JAGDISH KALME 8120828495 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA RAMTEKRAYYAT -

Historical Timeline of Hinduism in America 1780'S Trade Between

3/3/16, 11:23 AM Historical Timeline of Hinduism in America 1780's Trade between India and America. Trade started between India and America in the late 1700's. In 1784, a ship called "United States" arrived in Pondicherry. Its captain was Elias Hasket Derby of Salem. In the decades that followed Indian goods became available in Salem, Boston and Providence. A handful of Indian servant boys, perhaps the first Asian Indian residents, could be found in these towns, brought home by the sea captains.[1] 1801 First writings on Hinduism In 1801, New England writer Hannah Adams published A View of Religions, with a chapter discussing Hinduism. Joseph Priestly, founder of English Utilitarianism and isolater of oxygen, emigrated to America and published A Comparison of the Institutions of Moses with those of the Hindoos and other Ancient Nations in 1804. 1810-20 Unitarian interest in Hindu reform movements The American Unitarians became interested in Indian thought through the work of Hindu reformer Rammohun Roy (1772-1833) in India. Roy founded the Brahmo Samaj which tried to reform Hinduism by affirming monotheism and rejecting idolotry. The Brahmo Samaj with its universalist ideas became closely allied to the Unitarians in England and America. 1820-40 Emerson's discovery of India Ralph Waldo Emerson discovered Indian thought as an undergraduate at Harvard, in part through the Unitarian connection with Rammohun Roy. He wrote his poem "Indian Superstition" for the Harvard College Exhibition of April 24, 1821. In the 1830's, Emerson had copies of the Rig-Veda, the Upanishads, the Laws of Manu, the Bhagavata Purana, and his favorite Indian text the Bhagavad-Gita. -

Schisms of Swami Muktananda's Siddha Yoga

Marburg Journal of Religion: Volume 15 (2010) Schisms of Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga John Paul Healy Abstract: Although Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga is a relatively new movement it has had a surprising amount of offshoots and schismatic groups claiming connection to its lineage. This paper discusses two schisms of Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga, Nityananda’s Shanti Mandir and Shankarananda’s Shiva Yoga. These are proposed as important schisms from Siddha Yoga because both swamis held senior positions in Muktananda’s original movement. The paper discusses the main episodes that appeared to cause the schism within Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga and the subsequent growth of Shanti Mandir and Shiva Yoga. Nityananda’s Shanti Mandir and Shankarananda’s Shiva Yoga may be considered as schisms developing from a leadership dispute rather than doctrinal differences. These groups may also present a challenge to Gurumayi’s Siddha Yoga as sole holder of the lineage of Swami Muktananda. Because of movements such as Shanti Mandir and Shiva Yoga, Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga Practice continues and grows, although, it is argued in this paper that it now grows through a variety of organisations. Introduction Prior to Swami Muktananda’s death in 1982 Swami Nityananda was named his successor to Siddha Yoga; by 1985 he was deposed by his sister and co-successor Gurumayi. Swami Shankarananda, a senior Swami in Siddha Yoga, sympathetic to Nityananda also left the movement around the same time. However, both swamis with the support of devotees of Swami Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga, developed their own movements and today continue the lineage of their Guru and emphasise the importance of the Guru Disciple relationship within Swami Muktananda’s tradition. -

Aghoreshwar Bhagawan Ram and the Aghor Tradition

Syracuse University SURFACE Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Anthropology - Dissertations Affairs 12-2011 Aghoreshwar Bhagawan Ram and the Aghor Tradition Jishnu Shankar Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/ant_etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Shankar, Jishnu, "Aghoreshwar Bhagawan Ram and the Aghor Tradition" (2011). Anthropology - Dissertations. 93. https://surface.syr.edu/ant_etd/93 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Aghoreshwar Mahaprabhu Baba Bhagawan Ram Ji, a well-established saint of the holy city of Varanasi in north India, initiated many changes into the erstwhile Aghor tradition of ascetics in India. This tradition is regarded as an ancient system of spiritual or mystical knowledge by its practitioners and at least some of the practices followed in this tradition can certainly be traced back at least to the time of the Buddha. Over the course of the centuries practitioners of this tradition have interacted with groups of other mystical traditions, exchanging ideas and practices so that both parties in the exchange appear to have been influenced by the other. Naturally, such an interaction between groups can lead to difficulty in determining a clear course of development of the tradition. In this dissertation I bring together micro-history, hagiography, folklore, religious and comparative studies together in an attempt to understand how this modern day religious-spiritual tradition has been shaped by the past and the role religion has to play in modern life, if only with reference to a single case study. -

Festivals, Rituals and Vesas of Goddess Samaleswari of Sambalpur

Odisha Review October - 2012 Festivals, Rituals and Vesas of Goddess Samalesvari of Sambalpur Dr. P.K. Singh Goddess Samalesvari is worshipped as the Goddess Durga under the Semel trees. For presiding deity in most of the Sakta shrines of example at Bhatigaon under Barpali block of Western Odisha. She is worshipped in various Bargarh district, icon of Mahisamarddini Durga forms and figures such as in the case of is worshipped as Goddess Samalesvari. Also in Samalaesvari temple of Barpali and Sambalpur, case of Budhi Samalei of Suvarnapur, the She is worshipped as a large block of stone in presiding deity is a four-armed Durga. Thus the middle of which is a projection resembling Goddess Samalesvari is a popular deity in the the mouth of a cow; the length and breadth of Western extremity of this projection has Odisha. a groove of a thread breath which is called the mouth. As Rituals discussed by N. Senapati and B. Mohanty1, at both sides of When the Chauhan kings the projection, there are of Patna State came to rule depressions over which over Western Odisha, they between gold leave is placed tried to appease the local tribes as a substitute for eye. by accepting their deity According to some scholars2, Samalei as their Istadevi it is also described as a massive (tutelary deity) and thereby triangular rock with something manipulating their support for like a penis protruding at the good governance. According bottom, a unique image in the to noted scholar F. Deo3, the whole country, a rare relic of Chauhan king Balaram Dev the linga-yoni worship. -

UNESCO- IUCN Enhancing Our Heritage Project: Monitoring and Managing for Success in Natural World Heritage Sites

UNESCO- IUCN Enhancing Our Heritage Project: Monitoring and Managing for Success in Natural World Heritage Sites Final Management Effectiveness Evaluation Report Chitwan National Park, Nepal October 2007 Table of Content Project Background 1 Evaluation Process 2 The Project Workbook and Tool Kits 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION 4-10 2.0 CONTEXT ASSESSMENT 11-45 2.1 Major Site Values and Objectives 11 2.2. Identifying Threats 21 2.3 Relationship with Stakeholders/Partners 30 2.4 Review of National Context 43 3.0 PLANNING ASSESSMENT 46-57 3.1. Management Plan 46 3.2 Design Assessment 54 4.0 INPUTS AND PROCESS ASSESSMENT 58-62 4.1 Management Needs and Inputs for Staff 58 4.2 Equipments and Infrastructure 59 4.3 Management Needs and Inputs for Budget 61 5.0 ASSESSMENT OF MANAGEMENT PROCESSES 63-78 5.1 Management Structures and Systems 63 5.2 Resource Management 63 5.3 Management and Tourism 64 5.4 Management and Communities/Neighbours 64 6.0 OUTPUTS 79-83 6.1 Assessment of Management Plan Implementation 79 6.2 Assessment of Work/Site Output Indicators 81 7. OUTCOMES 84-96 7.1 Assessing the Outcomes of Management – Ecological Integrity 84 7.2 Assessing the Outcomes of Management – Achievement of Principal Objectives 93 1 List of Boxes Box 1: Historical Events in the Chitwan National Park 9 Box 2: IUCN-WCPA framework for Management Effectiveness Evaluation 10 Box 3: Tourism in Chitwan National Park 18-19 Box 4: Impacts of Insurgency on Biodiversity Conservation in Chitwan National Park 28 Box 5: Rhino Conservation in Chitwan National Park 29 Box 6: Partnership -

Ready to Get Married

SriSri ChakraChakra The Source of the Cosmos The Journal of the Sri Rajarajeswari Peetam, Rush, NY Blossom 16 Petal 3 September 2012 SeptemberSeptemberSeptember NewsletNewsletNewsletterterter Since the last issue... After returning from the In the latter part of July, Aiya camp ended, he had to honour a Toronto workshop Aiya and Amma left for Europe again, prior commitment he made to the conducted on June 2, he and but this time met up with Sri students in Australia and Amma remained in Toronto that Mathioli Saraswati (Sri Akka) for Singapore, and was on a plane to following week to perform about 10 days. visit them for about three weeks. various private pujas. On the 9th Aiya had to miss the first two While he was abroad, Aiya and 10th of June, they went to days of the Vibhuti Saivaite performed several workshops, Washington DC to perform a Immersion camp, but was there house pujas, public pujas and wedding and then came back to most of the week. Even before conducted university lectures. Canada to do another wedding in Ottawa on June 16th and 17th. Aiya was back in Rochester the weekend of the 23rd and 24th because he was teaching one of the ILS (Interactive Learning Sessions) classes. That week was also quite busy since everyone was preparing for the annual Alankara (Pratishta) festival from July 1 to 3. In the second week of July, Aiya Thanks to Mayuran Saththianathan and Amma went to England for a for sending in photos of Aiya’s private visit but then returned in homam/puja at the site of the time to conduct the Aadi upcoming Shree Shirdi Sai Amavasya puja at the temple. -

A QUICK INFORMATION for YOUR JOURNEY to NEPAL CONTENTS 1.About Nepal

TRAVELXLOG A QUICK INFORMATION FOR YOUR JOURNEY TO NEPAL CONTENTS 1.About Nepal..............................................01 2.Tourism Activities In Nepal...............02-03 3.Getting a Tourist Visa for Nepal........04-05 4.Access in Nepal........................................06 5.Accommodations......................................07 6.Restaurants...............................................07 7.Places to visit in Kathmandu valley.......08 8.Foreign Money Exchange.........................08 9.SIM Card.....................................................08 10.Domestic Airlines of Nepal.......................09 11.Travel Nepal by Road................................10 12.Hiring the Guide or other staff..................10 13.Where to travel in Nepal?..........................11 14.About Us.......................................................12 15.Contact Details............................................12 ABOUT NEPAL Nepal, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal, small landlocked country and borders China in the north and India in the south, east and west. Kathmandu is the capital city. It is the 49th largest country by population and 93rd largest country by area. It lies between latitudes 26° and 31°N, and longitudes 80° and 89°E. Nepal has a diverse geography, including fertile plains, sub-alpine forested hills, and eight of the world’s ten tallest mountains, including Mount Everest, the highest point on Earth. Kathmandu is the capital and the largest city. Nepal is a multi-ethnic country with Nepali as the official language. Nepal has five climatic zones, broadly corresponding to the altitudes. The tropical and subtropical zones lie below 1,200 meters (3,900 ft.), the temperate zone 1,200 to 2,400 meters (3,900 to 7,900 ft.), the cold zone 2,400 to 3,600 meters (7,900 to 11,800 ft.), the subarctic zone 3,600 to 4,400 meters (11,800 to 14,400 ft.), and the Arctic zone above 4,400 meters (14,400 ft.). -

Concept of Sadhus in Nepalese Society

RESEARCHER I II JULY- DECEMBER 2013 81 CONCEPT OF SADHUS IN NEPALESE SOCIETY Som Prasad Khatiwada Tribhuvan University [email protected] Abstract The concept of Sadhus is an old Hindu tradition started long ago from the system of Ashram in Indian Sub-continent. In general, human life is divided into four stages and the last stage is known as Sanyasa. When an old person becomes free from his family responsibilities then he practices peaceful activities. This stage of life is called Sanyasa and it is a form of Sadhu. Sadhus generally live in Asharams or temples in the group. In the past, they were forced to take weapons in their hands for the protection of their life and religion. Therefore, Akhadas were established in the place of ashramas to keep militant Sadhus. They do not have to keep greed, love, exceptions and trishna and their Yajnas should relate on the well-being of the universe. They are the means of study and they should be utilized to attract tourists in modern economic world. Key words: Akhada, Sadhu, Mahanta, Khaki, Trisna, Keshin, Japa and Tapa Introduction Sadhus are called Yogi, Saint, Bairagi and Sanyasi. They do not have any personal properties, houses, family and the family names. They are not allowed to follow particular religion and are not permitted to stay in a fixed center. Therefore, they move here and there and beg for his daily food. Sadhus are not allowed to store food and property for the RESEARCHER I II JULY- DECEMBER 2013 82 future. They are not allowed to keep the begged food for another day. -

Acknowledgement

vs ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Ecosystem based Adaptation (EbA) in Mountain Ecosystems in Nepal, Peru and Uganda aims to strengthen the capacity of these countries, which are particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts, through ecosystem based adaptation approaches. The project targets to strengthen the resiliency of ecosystems within these countries and reduce the vulnerability of local communities with particular emphasis on mountain ecosystems. The project is funded by the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) through its International Climate Initiative and is jointly implemented by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). In Nepal, the Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation (MoFSC)/ Department of Forest (DOF) is the implementing agency at the national level in partnership with UNDP, IUCN and UNEP while the Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment, (MoSTE) plays an overall coordination role. EbA is thankful to GENESIS Consultancy (P).Ltd and Green Governance Nepal for conducting Baseline and Socio-Economic Survey of the Ecosystem based Adaptation Project Area in Panchase. We would like to acknowledge Bhuvan Keshar Sharma, Kiran Timalsina, Roshani Rai, Surya Kumar Maharjan, Dr. Menaka Pant, Anish Joshi, Biplob Rakhal, Basanti Kumpakha, Dikshya Bohara, Suraj Thapa, and Prakash Thapa for their effort and invaluable contribution. January 2014 1 ABBREVIATIONS BMUB Germany’s Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety CBD Convention on Biological Diversity CC Climate Change EbA Ecosystem based Adaptation ES Ecosystem Services FGD Focus Group Discussion GGN Green Governance Nepal GIS Geographic Information System GPS Global Positioning System ha. -

Suggesting Śāntarasa in Shanti Mandir's Satsaṅga

81 ETHNOLOGIA ACTUALIS Vol. 17, No. 2/2017 PATRICK McCARTNEY Suggesting Śāntarasa in Shanti Mandir’s Satsaṅga: Ritual, Performativity and Ethnography in Yogaland Suggesting Śāntarasa in Shanti Mandir’s Satsaṅga: Ritual, Performativity and Ethnography in Yogaland PATRICK McCARTNEY Graduate School of Global Enviromental Studies Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan Anthropological Institute Nanzan University, Nagoya, Japan South and South East Asia Department Australian National University, Canberra, Australia [email protected] ABSTRACT Satsaṅga is a public domain where ideas related to transcendence and culturally- contingent “Truth” are suggested. This paper combines a longitudinal study of Shanti Mandir’s (www.shantimandir.com) satsaṅga, with close reading of local and non-local literary theories related to the performativity of satsaṅga and the doctrine of appreciating tranquillity (śāntarasavāda). This leads to the possibility of framing satsaṅga as a rasavat- kāvya (charming-literature) literary artefact; which we can regard as a type of hybrid campū-rasavat kāvya. Finally, from an interdisciplinary perspective, I provide a novel epistemological bricolage to understand the soteriological and sociological aims of satsaṅga from within the Temple of Peace (Shanti Mandir) organisation, and propose an analytical framework about how satsaṅga operates as a formal learning domain; where sādhaka-s (aspirants) attempt to gain access to a yoga-inspired disposition related to becoming (praśama), embodying and experiencing śānti (tranquillity), which occurs DOI: 10.2478/eas-2018-0005 © University of SS. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava. All rights reserved. 82 ETHNOLOGIA ACTUALIS Vol. 17, No. 2/2017 PATRICK McCARTNEY Suggesting Śāntarasa in Shanti Mandir’s Satsaṅga: Ritual, Performativity and Ethnography in Yogaland through learning to become śāntamūrti-s (embodiers of tranquillity) by appreciating śāntarasa (the aesthetic mood of tranquillity). -

Ecotourism Community

HARIYO BAN PROGRAM A STUDY ON PROMOTING COMMUNITY MANAGED ECOTOURISM IN CHAL & TAL 31 MAY, 2013 HARIYO BAN PROGRAM A STUDY ON PROMOTING IN CHAL & TaL HARIYO BAN PROGRAM A STUDY ON PROMOTING COMMUNITY MANAGED ECOTOURISM IN CHAL & TaL 31 MAY, 2013 © WWF 2014 All rights reserved Any reproduction of this publication in full or in part must mention the title and credit WWF. Published by WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program This publication is also available in www.wwfnepal.org/publications PO Box: 7660 Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal T: +977 1 4434820, F: +977 1 4438458 [email protected] www.wwfnepal.org/hariyobanprogram Authors This report was prepared by the Nepal Economic Forum, Krishna Galli, Lalitpur. The assessment team comprised: Sujeev Shakya, Prachanda Man Shrestha, Dr. Tej Bahadur Thapa, Sudip Bhaju, Shristi Singh, Raju Tuladhar. Photo credits Cover photo: © Nepal Economic Forum Disclaimer This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Nepal Economic Forum (NEF) and do not necessarily reflect the views of WWF, USAID or the United States Government. Publication Services Editing: Katherine Saunders Design and Layout: Big Stone Medium Hariyo Ban Program publication number: Report 020 Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................... i Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................