Features of Small Holder Goat Farming from Chitwan District of Bagmati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Rural Outmigration and Agricultural Land Use Change in the Gandaki Basin, Nepal

Applied Geography 124 (2020) 102278 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Applied Geography journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/apgeog Understanding rural outmigration and agricultural land use change in the Gandaki Basin, Nepal Amina Maharjan a,*, Ishaan Kochhar b, Vishwas Sudhir Chitale a, Abid Hussain a, Giovanna Gioli c,1 a International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), Kathmandu, Nepal b Harvesting India Private Limited, Chandigarh, India c Bath Spa University, Newton Park, Bath, UK 1. Introduction et al., 2019). Labour migration has become an important source of alternative and supplementary income (Maharjan et al., 2018). In Nepal, Agricultural land abandonment has become a global phenomenon as both internal and international labour migration have steadily increased a consequence of changing priorities in economic development, a over the past two decades. Internal migration patterns reveal that widening gap between agricultural and non-agricultural incomes, mostly, people are migrating from the hills and mountains to the plains. climate change vulnerabilities, and a gradual decrease in the rural The last population census reported a negative population growth rate in workforce engaged in agricultural production (Hussain et al., 2016; Liu 36 out of the 55 hill and mountain districts of the country (CBS, 2012). et al., 2014; MacDonald et al., 2000; Okahashi, 1996; Pointereau et al., In the fiscalyear 2015–16, remittances from international migrants were 2008; Prishchepov et al., 2013; Queiroz et al., 2014; Rigg et al., 2017; equivalent to about 30% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Riggs, 2006; Shirai et al., 2017; Shui et al., 2019). Since the 20th cen (MOF, 2017). -

Conservation and the Impact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal Joanne Mclean Charles Sturt University (Australia)

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 19 Number 2 Himalayan Research Bulletin; Special Article 8 Topic: The Tharu 1999 Conservation and the Impact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal Joanne McLean Charles Sturt University (Australia) Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation McLean, Joanne (1999) "Conservation and the Impact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal," HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 19 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol19/iss2/8 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Conservation and the linpact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal Joanne McLean Charles Sturt University (Australia) Since the establishment of the first national park in the United States in the nineteenth century, indig enous peoples have been forced to move from regions designated as parks. Some of these people have been relocated to other areas by the government, more often they have been told to leave the area and are given no alternatives (Clay, 1985:2). Introduction (Guneratne 1994; Skar 1999). The Thant are often de scribed as one people. However, many subgroups exist: The relocation of indigenous people from national Kochjla Tharu in the eastern Tarai, Chitwaniya and Desauri parks has become standard practice in developing coun in the central Tarai, and Kathariya, Dangaura and Rana tries with little regard for the impacts it imposes on a Tharu in the western Tarai (Meyer & Deuel, 1999). -

Nepal – Maoists – Chitwan – State Protection – Local Government – Ward Chairmen

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: NPL17502 Country: Nepal Date: 2 September 2005 Keywords: Nepal – Maoists – Chitwan – State protection – Local government – Ward Chairmen This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Can you provide information on the activities of Maoists in Chitwan and the ability of the authorities to provide protection for individuals against threats from Maoists? 2. Do the Maoists have an office in Chitwan? Letter head paper or contact address? 3. What is a Ward and a Ward Chairman? 4. Is there evidence of the Maoists targeting members of Municipal councils or Ward Chairmen? RESPONSE 1. Can you provide information on the activities of Maoists in Chitwan and the ability of the authorities to provide protection for individuals against threats from Maoists? Activities A December 2002 Research Response provides information on Maoists in Chitwan suggesting it is a quiet area and they are mainly active in remote villages (RRT Country Research 2002 Research Response NPL17502, 24 December, question 1 – Attachment 1). A recent news item from the al Jazeera website refers to the Maoist-controlled district of Chitwan (‘Nepal blast triggers hunt for Maoists’ 2005, al Jazeera website, source: AFP, 6 June http://english.aljazeera.net/NR/exeres/9F7BE0A5-E320-4C5B-BD03- 7151D63A574F.htm - accessed 1 September 2005 - Attachment 2). -

Anthropogenic Impacts on Flora Biodiversity in the Forests and Common Land of Chitwan, Nepal

Anthropogenic impacts on flora biodiversity in the forests and common land of Chitwan, Nepal by Ganesh P. Shivakoti Co-Director Population and Ecology Research Laboratory Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science Tribhuvan University, Rampur, Nepal e-mail: [email protected] Stephen A. Matthews Research Associate Population Research Institute The Pennsylvania State University 601 Oswald Tower University Park, PA 18602-6211 e-mail: [email protected] and Netra Chhetri Graduate Student Department of Geography The Pennsylvania State University 302 Walker Building University Park, PA 16802 e-mail: [email protected] DRAFT COPY September 1997 Acknowledgment: This research was supported by two grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (Grant #R01-HD31982 and Grant #RO1-HD33551). We wish to thank William Axinn (PI on these grants), Dirgha Ghimire and the staff at the Population and Ecology Research Laboratory (PERL), IAAS, Nepal who helped collect the flora and common land data. Population growth and deforestation are serious problems in Chitwan and throughout Nepal. In this paper we explore the effect of social and demographic driving forces on flora diversity in Nepal. Specifically, we focus our attention on the flora diversity in three forested areas surrounding a recently deforested, settled and cultivated rural area - the Chitwan District. We have collected detailed counts of trees, shrubs, and grasses along the edge and in the interior of each forested area, and for common land throughout the settled area. Our sampling frame (described in the paper) allows us to construct detailed ordination and classification measures of forest floral diversity. Using techniques from quantitative ecology we can quantify species diversity (relative density, frequency and abundancy), and specifically measure the 'evenness' and 'richness' of the flora in the forested areas and common land. -

National Economic Census 2018 Analytical Report

Analytical Report GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Analytical Report Informal Sector Informal Sector National Planning Commission Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal March 2021 GOVERNMENTGOVERNMENT OFOF NEPAL NationalNational EconomicEconomic CensusCensus 20182018 AnalyticalAnalytical ReportReport Food aInformalnd Bevera Sectorge Industry NationalNationa Planningl Planning CCommissionommission CentralCentral BureauBureau ofof StatisticsStatistics Kathmandu,Kathmandu, NepalNepal MarchMarch 2021 Published by: Central Bureau of Statistics Address: Ramshahpath, Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal. Phone: +977-1-4100524, 4245947 Fax: +977-1-4227720 P.O. Box No: 11031 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] ISBN: 978-9937-0-8822-0 iii ivLY v YL vii YLLL Government of Nepal National Planning Commission Central Bureau of Statistics Director General Director General ACKNOWLEDGEMENTACKNOWLEDGEMENT ItIt is is my my pleasure pleasure toto release release AnalyticalAnalytical Report on Informal SectorSector of of National National Economic Economic Census Census 2018. 2018. CentralCentral BureauBureau ofof StatisticsStatistics (CBS)(CBS) conducted thethe firstfirst NationalNational Economic Economic Census Census 2018 2018 (NEC2018) (NEC2018) from from AprilApril toto JuneJune 2018, coveringcovering the the entire entire territory territory of ofNepal. Nepal. Its Itsmain main objective objective was wasto know to know the nature the nature of the of theeconomic economic char characteristicsacteristics on the on Nepalese the Nepalese economy. economy. CBS has CBS already has a releasedlready released National National Report Series Report Series1,2, and 1,2, 3, andProvincial 3, Provincial Summary Reports, Reports, National National Summary Summary Reports Reports in Nepali language,language, National National Profile Profile seriesseries 1,1, 2,2, andand 3,3, AnalyticalAnalytical Report No.1 andand No.No. 2,2, WardWard Profile Profile Series Series 1 1a andnd 2 2for for the the users. -

Vulnerability and Impacts Assessment for Adaptation Planning In

VULNERABILITY AND I M PAC T S A SSESSMENT FOR A DA P TAT I O N P LANNING IN PA N C H A S E M O U N TA I N E C O L O G I C A L R E G I O N , N EPAL IMPLEMENTING AGENCY IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS SUPPORTED BY Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation, Department of Forests UNE P Empowered lives. Resilient nations. VULNERABILITY AND I M PAC T S A SSESSMENT FOR A DA P TAT I O N P LANNING IN PA N C H A S E M O U N TA I N E C O L O G I C A L R E G I O N , N EPAL Copyright © 2015 Mountain EbA Project, Nepal The material in this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit uses, without prior written permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. We would appreciate receiving a copy of any product which uses this publication as a source. Citation: Dixit, A., Karki, M. and Shukla, A. (2015): Vulnerability and Impacts Assessment for Adaptation Planning in Panchase Mountain Ecological Region, Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal: Government of Nepal, United Nations Environment Programme, United Nations Development Programme, International Union for Conservation of Nature, German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety and Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-Nepal. ISBN : 978-9937-8519-2-3 Published by: Government of Nepal (GoN), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) and Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-Nepal (ISET-N). -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Enterprises for Self Employment in Banke and Dang

Study on Enterprises for Self Employment in Banke and Dang Prepared for: USAID/Nepal’s Education for Income Generation in Nepal Program Prepared by: EIG Program Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry Shahid Sukra Milan Marg, Teku, Kathmandu May 2009 TABLE OF CONTENS Page No. Acknowledgement i Executive Summary ii 1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 9 2 Objective of the Study ....................................................................................................... 9 3 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 9 3.1 Desk review ............................................................................................................... 9 3.2 Focus group discussion/Key informant interview ..................................................... 9 3.3 Observation .............................................................................................................. 10 4 Study Area ....................................................................................................................... 10 4.1 Overview of Dang and Banke district ...................................................................... 10 4.2 General Profile of Five Market Centers: .................................................................. 12 4.2.1 Nepalgunj ........................................................................................................ -

Nepal's Menstrual Movement

Implemented by: In Cooperation with: NEPAL’S MENSTRUAL MOVEMENT How ‘MenstruAction’ is making life better for girls and women in Nepal — month after month 1 FOREWORD ROLAND SCHÄFER, GERMAN AMBASSADOR TO NEPAL 03 FOREWORD DR. PUSHPA CHAUDHARY 05 FOREWORD DR. MARNI SOMMER 06 INTRODUCTION 07 THE ANCIENT PRACTICE OF CHHAUPADI 08 THE SCALE OF THE PROBLEM: SOME FACTS AND FIGURES 10 Content Practice of Chhaupadi 11 Menstruation product access and usage 11 Other restrictions 12 Sanitation 13 THE STORY SO FAR 14 Right to informed choice 17 Moving the MHM agenda forward 18 Working together through the MHM Practitioner Alliance 19 MENSTRUACTIVISTS. SOME MOVERS AND SHAKERS BEHIND MHM 20 MHM is the biggest topic around 21 The need for better data and understanding of the issues 23 Reflecting on restrictive practices through film making 25 Five Days 27 WATER AND SANITATION. THE KEY TO BETTER MENSTRUAL HYGIENE 28 Nepal’s geography is the biggest challenge 29 Addressing menstrual issues through WASH programmes 31 EDUCATION TO TACKLE TABOOS 32 The government is incorporating MHM issues into the school curriculum 33 AWARENESS AND EDUCATION IN ACTION: THE EXAMPLE OF BIDUR MUNICIPALITY 34 Raising awareness about menstrual health and hygiene management 35 Allocating resources to schools for MHM 36 Working with young people 38 Using radio to break down taboos 39 INVENTIONS, INNOVATIONS AND SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS 40 Producing low cost sanitary pads 41 Homemade eco-friendly, reusable cloth sanitary pads 42 ‘Wake Up, Kick Ass’ 43 Nepal’s first sanitary napkin -

Final Report

Final Report On Application of Community Based Adaptation Measures to Weather and Climate related Disasters (WCD) in Western Nepal: Preparation for the Potential Climate Change Signal. May 2009 Himalayan Climate Center Kathmandu, Nepal Contents Page Acronyms i Chapter 1: Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Study Site: Putalibazaar Municipality and Community Based Disaster Preparedness Units 3 1.3 Project Team 7 Chapter 2: Methodology and Activities 8 2.1 Background 8 2.1.1 Technical Approaches 8 2.1.2 Participatory Approaches 8 2.2 Activities 10 2.2.1 First participatory workshop 10 2.2.2 Second Participatory Workshop 13 2.2.3 Third Participatory Workshop 15 2.2.4 Consultation Meetings 19 2.2.5 Trainings 20 2.2.5.1 Training workshop on application of weather forecasting 20 2.2.5.2 Training on Insurance 21 2.2.6 Socio-economic Survey 23 2.2.7 Hydrological Survey 23 Chapter 3: Socio-economic Study 24 3.1 Background 24 3.2 Methodology 24 3.3 Socio-economic Condition 25 3.3.1 Ethnicity, Family and Population 25 3.3.2 Assets 28 3.3.2.1 Housing building 28 3.3.2.2 Land 30 3.3.2.3 Livestock 31 3.3.2.4 Other household items 32 3.3.3 Income and Expenditure 32 3.4 Natural Disaster and Mitigation Efforts 34 3.4.1 Events and Losses 34 3.4.2 Mitigation Efforts 35 3.5 People’s Perception 36 3.5.1 Disaster 36 1 3.5.2 Climate Change 37 3.5.3 Insurance 38 3.5.4 Dissemination of Weather and Climate Information 39 Chapter 4: Climate Change and Community Awareness 41 4.1 Background 41 4.2 Climate change in Putalibazaar 41 4.2.1 Observed data Analysis 41 -

Krishna Kaphle, Bvsc and AH,,GHC, ELT, Phd

Krishna Kaphle, BVSc and AH,,GHC, ELT, PhD Current Position: Director, Veterinary Teaching Hospital and As- sociate Professor at Department of Theriogenology Institution: Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science Tribhuvan University, Paklihawa Campus, Sidharthanagar-1, Rupandehi, Lumbini, Nepal E-mails and phone: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Phone: : +977-71-506150; Cell: 9845056734 Research Interest: ONE HEALTH ADVOCATING VETERINARIAN (THERIOGENOLOGIST) Objective: In pursuit of establishing best approach for delivery of animal health, animal welfare and public health concerns in Nepalese society. Get deeper in understanding the science behind origin of life. Beliefs: Engaged faculty and motivated student make the teach- ing and learning meaningful and nothing transform society bet- ter than right education. MAJOR ROLES, RESPONSIBILITIES AND PUBLICATIONS Education Aug 2001 – May 2006 (PhD) -National Taiwan University,, Taipei, Tai- wan, Republic Of China (ROC). Aug 1991 – 1997 (BVSc and AH) -Rampur Campus, Institute of Agri- culture and Animal Science (IAAS), Tribhuvan University (TU), Bharat- pur, Chitwan, Bagmati, Nepal. Responsibilities Assistant Professor: since 2055-01-15 at Rampur Campus, IAAS, TU. Hostel Warden, Sports Coach, Student Welfare Chief, member of various committees, at IAAS, TU. Advisory role for various students clubs, coordinator of national and regional events related with professional, sports and leadership training. Editorial roles for IAAS Journal, NVA Journal, The Blue Cross and multiple others. Department Head of Theriogenology- (April 10th 2009 and again from July 2021), IAAS, TU. Stints as Member secretary Internship Advisory Committee, Subject Matter Com- mittee (Veterinary Science) now as member, Member of Faculty Board (2018-). Advisor of Internship students (~20) and PG students as minor advisor (10). -

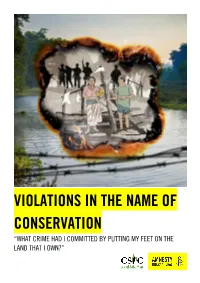

Violations in the Name of Conservation “What Crime Had I Committed by Putting My Feet on the Land That I Own?”

VIOLATIONS IN THE NAME OF CONSERVATION “WHAT CRIME HAD I COMMITTED BY PUTTING MY FEET ON THE LAND THAT I OWN?” Amnesty International is a movement of 10 million people which mobilizes the humanity in everyone and campaigns for change so we can all enjoy our human rights. Our vision is of a world where those in power keep their promises, respect international law and are held to account. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and individual donations. We believe that acting in solidarity and compassion with people everywhere can change our societies for the better. © Amnesty International 2021 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Illustration by Colin Foo (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Photo: Chitwan National Park, Nepal. © Jacek Kadaj via Getty Images https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2021 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 31/4536/2021 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1.1 PROTECTING ANIMALS, EVICTING PEOPLE 5 1.2 ANCESTRAL HOMELANDS HAVE BECOME NATIONAL PARKS 6 1.3 HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS BY THE NEPAL ARMY 6 1.4 EVICTION IS NOT THE ANSWER 6 1.5 CONSULTATIVE, DURABLE SOLUTIONS ARE A MUST 7 1.6 LIMITED POLITICAL WILL 8 2.