Weinberger-Powell and Transformation Perceptions of American Power from the Fall of Saigon to the Fall of Baghdad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quarterly Update on Conflict and Diplomacy Source: Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol

Quarterly Update on Conflict and Diplomacy Source: Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 32, No. 4 (Summer 2003), pp. 128-149 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Institute for Palestine Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jps.2003.32.4.128 . Accessed: 25/03/2015 15:58 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and Institute for Palestine Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Palestine Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 66.134.128.11 on Wed, 25 Mar 2015 15:58:14 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions QUARTERLY UPDATE ON CONFLICT AND DIPLOMACY 16 FEBRUARY–15 MAY 2003 COMPILED BY MICHELE K. ESPOSITO The Quarte rlyUp date is asummaryofbilate ral, multilate ral, regional,andinte rnationa l events affecting th ePalestinians andth efutureofth epeaceprocess. BILATERALS 29foreign nationals had beenkilled since 9/28/00. PALESTINE-ISRAEL Positioningf orWaronIraq Atthe opening of thequarter, Ariel Tokeep up the appearance of Sharon had beenreelected PM of Israel movementon thepeace process in the and was in theprocess of forming a run-up toawar on Iraq, theQuartet government.U.S. -

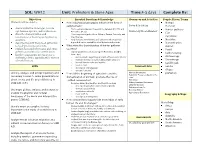

SOL: WHI.2 Unit: Prehistory & Stone Ages Time:4-5 Days Complete

SOL: WHI.2 Unit: Prehistory & Stone Ages Time:4-5 days Complete By: Objectives Essential Questions & Knowledge Resources and Activities People, Places, Terms Students will be able to: How did physical geography influence the lives of Nomad early humans? Notes & Activities Hominid characterize the stone ages, bronze Homo sapiens emerged in east Africa between 100,000 and Hunter-gatherer age, human species, and civilizations. 400,000 years ago. Prehistory Vocab Handout Clan describe characteristics and Homo sapiens migrated from Africa to Eurasia, Australia, and innovations of hunting and gathering the Americas. Paleolithic societies. Early humans were hunters and gatherers whose survival Neolithic describe the shift from food gathering depended on the availability of wild plants and animals. Domestication to food-producing activities. What were the characteristics of hunter gatherer Artifact explain how and why towns and cities societies? Fossil grew from early human settlements. Hunter-gatherer societies during the Paleolithic Era (Old Carbon dating list the components necessary for a Stone Age) Archaeology civilization while applying their themes o were nomadic, migrating in search of food, water, shelter of world history. o invented the first tools, including simple weapons Stonehenge o learned how to make and use fire Catal hoyuk Skills o lived in clans Internet Links Jericho o developed oral language o created “cave art.” Aleppo Human Organisms Identify, analyze, and interpret primary and How did the beginning of agriculture and the prehistory Paleolithic Era versus Neolithic Era secondary sources to make generalizations domestication of animals promote the rise of chart about events and life in world history to settled communities? Prehistory 1500 A.D. -

Caspar Weinberger and the Reagan Defense Buildup

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-2013 Direct Responsibility: Caspar Weinberger and the Reagan Defense Buildup Robert Howard Wieland University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the American Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wieland, Robert Howard, "Direct Responsibility: Caspar Weinberger and the Reagan Defense Buildup" (2013). Dissertations. 218. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/218 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi DIRECT RESPONSIBILITY: CASPAR WEINBERGER AND THE REAGAN DEFENSE BUILDUP by Robert Howard Wieland Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School Of The University of Southern Mississippi In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2013 ABSTRACT DIRECT RESPONSIBILITY: CASPAR WEINBERGER AND THE REAGAN DEFENSE BUILDUP by Robert Howard Wieland December 2013 This dissertation explores the life of Caspar Weinberger and explains why President Reagan chose him for Secretary of Defense. Weinberger, not a defense technocrat, managed a massive defense buildup of 1.5 trillion dollars over a four year period. A biographical approach to Weinberger illuminates Reagan’s selection, for in many ways Weinberger harkens back to an earlier type of defense manager more akin to Elihu Root than Robert McNamara; more a man of letters than technocrat. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

America's Longest

AMERICA’S LONGEST WAR I. Why did the U.S. send troops to Vietnam? A. Ho Chi Minh defeated the French in 1954 and Vietnam was split into North and South. B. North Vietnam was led by Communist Ho Chi Minh- South Vietnam was led by U.S. backed Diem. C. Many South Vietnamese opposed U.S. backed Diem. D. Vietcong were South Vietnamese guerrillas who were backed by the North and fought against the South’s government E. President John F. Kennedy believed in the Domino Theory, the idea that if one Southeast Asian country fell to communism, the rest would also, like a row of dominos. F. In 1961, he sent military advisors to help Diem fight the Vietcong G. 1963- Lyndon Johnson became President and sent more aid to South Vietnam H. 1964- Gulf of Tonkin Resolution- after a U.S. ship is attacked, Congress passed this which allowed President Johnson to take “all necessary measures” to prevent another attack I. Thus, the war escalated and by 1968 there were over 500,000 troops fighting in the Vietnam War. J. American soldiers faced many hardships fighting a “guerilla war” in jungle terrain, going on search and destroy missions. A Viet Cong prisoner awaits interrogation at a Special Forces detachment in Thuong Duc, Vietnam, 15 miles (25 km) west of Danang, January 1967 Troops of the 1st Air Cavalry Division check houses while patrolling an area 25 miles (40 km) north of Qui Nhon as part of Operation Thayer, October 1966. The mission was designed to clear out a mountain range where two battalions of North Vietnamese were believed to be preparing for an attack on an airstrip. -

1973 NGA Annual Meeting

Proceedings OF THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE 1973 SIXTY-FIFTH ANNUAL MEETING DEL WEBB'S SAHARA TAHOE. LAKE TAHOE, NEVADA JUNE 3-61973 THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE IRON WORKS PIKE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40511 Published by THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE IRON WORKS PIKE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40511 CONTENTS Executive Committee Rosters . vi Other Committees of the Conference vii Governors and Guest Speakers in Attendance ix Program of the Annual Meeting . xi Monday Session, June 4 Welcoming Remarks-Governor Mike O'Callaghan 2 Address of the Chairman-Governor Marvin Mandel 2 Adoption of Rules of Procedure 4 "Meet the Governors" . 5 David S. Broder Lawrence E. Spivak Elie Abel James J. Kilpatrick Tuesday Session, June 5 "Developing Energy Policy: State, Regional and National" 46 Remarks of Frank Ikard . 46 Remarks of S. David Freeman 52 Remarks of Governor Tom McCall, Chairman, Western Governors' Conference 58 Remarks of Governor Thomas J. Meskill, Chairman, New England Governors' Conference . 59 Remarks of Governor Robert D. Ray, Chairman, Midwestern Governors' Conference 61 Remarks of Governor Milton J. Shapp, Vice-Chairman, Mid-Atlantic Governors' Conference . 61 Remarks of Governor George C. Wallace, Chairman, Southern Governors' Conference 63 Statement by the Committee on Natural Resources and Environmental Management, presented by Governor Stanley K. Hathaway 65 Discussion by the Governors . 67 "Education Finance: Challenge to the States" 81 Remarks of John E. Coons . 81 Remarks of Governor Wendell R. Anderson 85 Remarks of Governor Tom McCall 87 Remarks of Governor William G. Milliken 88 iii Remarks of Governor Calvin L. Rampton 89 Discussion by the Governors . 91 "New Directions in Welfare and Social Services" 97 Remarks by Frank Carlucci 97 Discussion by the Governors . -

Remote Warfare Interdisciplinary Perspectives

Remote Warfare Interdisciplinary Perspectives ALASDAIR MCKAY, ABIGAIL WATSON & MEGAN KARLSHØJ-PEDERSEN This e-book is provided without charge via free download by E-International Relations (www.E-IR.info). It is not permitted to be sold in electronic format under any circumstances. If you enjoy our free e-books, please consider leaving a small donation to allow us to continue investing in open access publications: http://www.e-ir.info/about/donate/ i Remote Warfare Interdisciplinary Perspectives EDITED BY ALASDAIR MCKAY, ABIGAIL WATSON AND MEGAN KARLSHØJ-PEDERSEN ii E-International Relations www.E-IR.info Bristol, England 2021 ISBN 978-1-910814-56-7 This book is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC 4.0 license. You are free to: • Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format • Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material Under the following terms: • Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. • NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission. Please contact [email protected] for any such enquiries, including for licensing and translation requests. Other than the terms noted above, there are no restrictions placed on the use and dissemination of this book for student learning materials/scholarly use. Production: Michael Tang Cover Image: Ruslan Shugushev/Shutterstock A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Commission on Protecting and Reducing Government Secrecy

S. Doc. 105-2 REPORT of the COMMISSION ON PROTECTING AND REDUCING GOVERNMENT SECRECY PURSUANT TO PUBLIC LAW 236 103RD CONGRESS This report can be found on the Internet at the Government Printing Office’s (GPO) World Wide Web address: http://www.access.gpo.gov/int For further information about GPO’s Internet service, call (202) 512-1530. For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-9328 ISBN 0-16-054119-0 The Commission on Protecting and Reducing Government Secrecy Daniel Patrick Moynihan, New York, Chairman Larry Combest, Texas, Vice Chairman John M. Deutch, Massachusetts Jesse Helms, North Carolina Martin C. Faga, Virginia Ellen Hume, District of Columbia Alison B. Fortier, Maryland Samuel P. Huntington, Massachusetts Richard K. Fox, District of Columbia John D. Podesta, District of Columbia Lee H. Hamilton, Indiana Maurice Sonnenberg, New York Staff Eric R. Biel, Staff Director Jacques A. Rondeau, Deputy Staff Director Sheryl L. Walter, General Counsel Michael D. Smith, Senior Professional Staff Joan Vail Grimson, Counsel for Security Policy Sally H. Wallace, Senior Professional Staff Thomas L. Becherer, Research and Policy Director Michael J. White, Senior Professional Staff Carole J. Faulk, Administrative Officer Paul A. Stratton, Administrative Officer (1995) Cathy A. Bowers, Senior Professional Staff Maureen Lenihan, Research Associate Gary H. Gower, Senior Professional Staff Terence P. Szuplat, Research Associate John R. Hancock, Senior Professional Staff Pauline M. Treviso, Research Associate Appointments to the Commission By the President of the United States The Honorable John M. Deutch, Belmont, MA Mr. John D. Podesta, Washington, DC Ambassador Richard K. -

Power Projection and Force Deployment Under Reagan

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons War and Society (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Fall 12-20-2019 The Ladle and the Knife: Power Projection and Force Deployment under Reagan Mathew Kawecki Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/war_and_society_theses Part of the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Kawecki, Mathew. The Ladle and the Knife: Power Projection and Force Deployment under Reagan. 2019. Chapman University, MA Thesis. Chapman University Digital Commons, https://doi.org/10.36837/ chapman.000095 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in War and Society (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ladle and the Knife: Power Projection and Force Deployment under Reagan A Thesis by Mathew D. Kawecki Chapman University Orange, CA Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in War and Society Studies December 2019 Committee in charge: Gregory Daddis, Ph.D., Chair Robert Slayton, Ph.D. Alexander Bay, Ph.D. The thesis ofMathew D. Kawecki is approved. Ph.D., Chair Eabert Slalton" Pir.D AlexanderBa_y. Ph.D September 2019 The Ladle and the Knife: Power Projection and Force Deployment under Reagan Copyright © 2019 by Mathew D. Kawecki III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Greg Daddis, for his academic mentorship throughout the thesis writing process. -

Savings Bank of Manchester Reily the Latest ABC-Washington Post Get More Time Here I Would Have Zoning Changed to Planned Resi and Organization Department

20 - MANCHESTER HERALD. Saturday, March 31, 1984 BUSINESS Marvin Gaya’s father Private coalition plans Math team charged with murder waste cleanup program leads state Decisions on housing piague the elderiy .. page 4 page 20 ... page 10 The newspapers and magazines these days are so But the bright side is that the variety of resources to house: the stairs, kitchens and bathrooms. loaded with ads (or both new and already help the elderly solve these dilemmas is increasing — For a free phone consultation, you call the centerm well-developed retirement communities that you and is to some extent keeping pace with the huge Washington. D.C. (202) 466-6896 or you can request tte- might conclude that our nation's elderly plan to pack Your growth of our population age 65 and over'. publications list of the Barrier-Free Environment by. w writing Suite 700, 1015 15th St., N.W., Washington,* up and move the day after retirement begins. • Several states and localities have reduced Not so. An overwhelming “ 70 percent of Americans Money's property taxes or created a sliding scale of D.C. 20005. Enclose a self-addressed, stamped,, Sunny today; Manchester, Conn, age 65 and over will die at the same address where abatements for the elderly on limited incomes. Local business-size envelope. ' they celebrated their 65th birthday,” says Leo Worth tax assessors will know whether yours is such a Based on your queries, the staff can d evi» a warm Tuesday Monday, April'2, 1984 customized information packet for you, says John Baldwin, housing coordinator of the American Sylvia Porter community. -

US Military Intervention in the Post-Cold War

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-29-2014 U.S. Military Intervention in the Post-Cold War Era: A Case Study Analysis of Presidential Decision Making Dennis N. Ricci University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Ricci, Dennis N., "U.S. Military Intervention in the Post-Cold War Era: A Case Study Analysis of Presidential Decision Making" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 364. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/364 U.S. Military Intervention in the Post-Cold War Era: A Case-Study Analysis of Presidential Decision Making Dennis N. Ricci, Ph.D. University of Connecticut 2014 ABSTRACT The primary focus of this study is to explain presidential decision making, specifically whether to intervene militarily or not in a given circumstance in the Post-Cold War era. First, we define military intervention as the deployment of troops and weaponry in active military engagement (not peacekeeping). The cases in which we are interested involve the actual or intended use of force (“boots on the ground”), in other words, not drone attacks or missile strikes. Thus, we substantially reduce the number of potential cases by excluding several limited uses of force against Iraq, Sudan, and Afghanistan in the 1990s. Given the absence of a countervailing force or major power to serve as deterrent, such as the Soviet enemy in the Cold War period, there are potentially two types of military interventions: (1) humanitarian intervention designed to stop potential genocide and other atrocities and (2) the pre-emptive reaction to terrorism or other threats, such as under the Bush Doctrine. -

DEADBEAT DONORS Voters Demon- Was on Its Way to the Desk of Gov

★★ PRICES MAY VARY OUTSIDE METROPOLITAN WASHINGTON AREA CLOUDY – HIGH 60, LOW 39: DETAILS B12 WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 3, 2014 washingtontimes.com $1.00 POLITICS IMMIGRATION Obama fl ip-fl ops GOP struggles with strategy stump Johnson to fi ght Obama’s amnesty Admits unknown border status BY S.A. MILLER AND STEPHEN DINAN through the end of the fi scal year, reluctant to wait until March, THE WASHINGTON TIMES while carving out funding for and others said they couldn’t vote BY STEPHEN DINAN Obama’s 2010 prediction that an homeland security programs in a for any bill that didn’t try to ban THE WASHINGTON TIMES amnesty would lead to a surge House Republicans vowed separate measure that would last Mr. Obama’s policy — leaving in illegal immigration, and ques- Tuesday to confront President until early next year, when Con- Republican leaders wondering President Obama’s own words tioned the veracity of one law- Obama’s temporary amnesty for gress would revisit the amnesty whether they had enough support continue to be a major prob- maker who played a clip of Mr. illegal immigrants, but they con- controversy. to move ahead. lem for his defenders, including Obama’s words from last week, tinued to wrestle with how to do The approach would avoid a “This is a serious breach of our Homeland Security Secretary when the president said he’d it, as conservatives balked at the government shutdown and pre- Constitution. It’s a serious threat Jeh Johnson, the administra- taken “action to change the law” INSIDE GOP leadership’s plan to put off serve the GOP’s chance to fi ght to our system of government and, tion’s top immigration lawyer, on immigration.