Good Practice for Housing Male Laboratory Mice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table S1. Nakharuthai and Srisapoome (2020)

Primer name Nucleotide sequence (5’→3’) Purpose CXC-1F New TGAACCCTGAGCTGAAGGCCGTGA Real-time PCR CXC-1R New TGAAGGTCTGATGAGTTTGTCGTC Real-time PCR CXC-1R CCTTCAGCTCAGGGTTCAAGC Genomic PCR CXC-2F New GCTTGAACCCCGAGCTGAAAAACG Real-time PCR CXC-2R New GTTCAGAGGTCGTATGAGGTGCTT Real-time PCR CXC-2F CAAGCAGGACAACAGTGTCTGTGT 3’RACE CXC-2AR GTTGCATGATTTGGATGCTGGGTAG 5’RACE CXC-1FSB AACATATGTCTCCCAGGCCCAACTCAAAC Southern blot CXC-1RSB CTCGAGTTATTTTGCACTGATGTGCAA Southern blot CXC1Exon1F CAAAGTGTTTCTGCTCCTGG Genomic PCR On-CXC1FOverEx CATATGCAACTCAAACAAGCAGGACAACAGT Overexpression On-CXC1ROverEx CTCGAGTTTTGCACTGATGTGCAATTTCAA Overexpression On-CXC2FOverEx CATATGCAACTCAAACAAGCAGGACAACAGT Overexpression On-CXC2ROverEx CTCGAGCATGGCAGCTGTGGAGGGTTCCAC Overexpression β-actinrealtimeF ACAGGATGCAGAAGGAGATCACAG Real-time PCR β-actinrealtimeR GTACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACAT Real-time PCR M13F AAAACGACGGCCAG Nucleotide sequencing M13R AACAGCTATGACCATG Nucleotide sequencing UPM-long (0.4 µM) CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT RACE PCR UPM-short (2 µM) CTAATAC GACTCACTATA GGGC RACE PCR Table S1. Nakharuthai and Srisapoome (2020) On-CXC1 Nucleotide (%) Amino acid (%) On-CXC2 Nucleotide (%) Amino acid (%) Versus identity identity similarity Versus identity identity Similarity Teleost fish 1. Rock bream, Oplegnathus fasciatus (AB703273) 64.5 49.1 68.1 O. fasciatus 70.7 57.7 75.4 2. Mandarin fish, Siniperca chuatsi (AAY79282) 63.2 48.1 68.9 S. chuatsi 70.5 54.0 78.8 3. Atlantic halibut, Hippoglossus hippoglossus (ACY54778) 52.0 39.3 51.1 H. hippoglossus 64.5 46.3 63.9 4. Common carp IL-8, Cyprinus carpio (ABE47600) 44.9 19.1 34.1 C. carpio 49.4 21.9 42.6 5. Rainbow trout IL-8, Oncorhynchus mykiss (CAC33585) 44.0 21.3 36.3 O. mykiss 47.3 23.7 44.4 6. Japanese flounder IL-8, Paralichthys olivaceus (AAL05442) 48.4 25.4 45.9 P. -

Mouse Models of Human Disease an Evolutionary Perspective Robert L

170 commentary Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health [2016] pp. 170–176 doi:10.1093/emph/eow014 Mouse models of human disease An evolutionary perspective Robert L. Perlman* Department of Pediatrics, The University of Chicago, 5841 S. Maryland Ave, MC 5058, Chicago, IL 60637, USA *E-mail: [email protected] Received 31 December 2015; revised version accepted 12 April 2016 ABSTRACT The use of mice as model organisms to study human biology is predicated on the genetic and physio- logical similarities between the species. Nonetheless, mice and humans have evolved in and become adapted to different environments and so, despite their phylogenetic relatedness, they have become very different organisms. Mice often respond to experimental interventions in ways that differ strikingly from humans. Mice are invaluable for studying biological processes that have been conserved during the evolution of the rodent and primate lineages and for investigating the developmental mechanisms by which the conserved mammalian genome gives rise to a variety of different species. Mice are less reliable as models of human disease, however, because the networks linking genes to disease are likely to differ between the two species. The use of mice in biomedical research needs to take account of the evolved differences as well as the similarities between mice and humans. KEYWORDS: allometry; cancer; gene networks; life history; model organisms transgenic, knockout, and knockin mice, have If you have cancer and you are a mouse, we can provided added impetus and powerful tools for take good care of you. Judah Folkman [1] mouse research, and have led to a dramatic increase in the use of mice as model organisms. -

Micromys Minutus)

Acta Theriol (2013) 58:101–104 DOI 10.1007/s13364-012-0102-0 SHORT COMMUNICATION The origin of Swedish and Norwegian populations of the Eurasian harvest mouse (Micromys minutus) Lars Råberg & Jon Loman & Olof Hellgren & Jeroen van der Kooij & Kjell Isaksen & Roar Solheim Received: 7 May 2012 /Accepted: 17 September 2012 /Published online: 29 September 2012 # Mammal Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences, Białowieża, Poland 2012 Abstract The harvest mouse (Micromys minutus) occurs the Mediterranean, from France to Russia and northwards throughout most of continental Europe. There are also two to central Finland (Mitchell-Jones et al. 1999). Recently, isolated and recently discovered populations on the it has also been found to occur in Sweden and Norway. Scandinavian peninsula, in Sweden and Norway. Here, we In 1985, an isolated population was discovered in the investigate the origin of these populations through analyses province of Dalsland in western Sweden (Loman 1986), of mitochondrial DNA. We found that the two populations and during the last decade, this population has been on the Scandinavian peninsula have different mtDNA found to extend into the surrounding provinces as well haplotypes. A comparison of our haplotypes to published as into Norway. The known distribution in Norway is sequences from most of Europe showed that all Swedish and limited to a relatively small area close to the Swedish Norwegian haplotypes are most closely related to the border, in Eidskog, Hedmark (van der Kooij et al. 2001; haplotypes in harvest mice from Denmark. Hence, the two van der Kooij et al., unpublished data). In 2007, another populations seem to represent independent colonisations but population was discovered in the province of Skåne in originate from the same geographical area. -

Laboratory Animal Management: Rodents

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/2119 SHARE Rodents (1996) DETAILS 180 pages | 6 x 9 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-04936-8 | DOI 10.17226/2119 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Committee on Rodents, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council FIND RELATED TITLES SUGGESTED CITATION National Research Council 1996. Rodents. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/2119. Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Rodents i Laboratory Animal Management Rodents Committee on Rodents Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources Commission on Life Sciences National Research Council NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS Washington, D.C.1996 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Rodents ii National Academy Press 2101 Constitution Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20418 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. -

A Guide to Mites

A GUIDE TO MITES concentrated in areas where clothes constrict the body, or MITES in areas like the armpits or under the breasts. These bites Mites are arachnids, belonging to the same group as can be extremely itchy and may cause emotional distress. ticks and spiders. Adult mites have eight legs and are Scratching the affected area may lead to secondary very small—sometimes microscopic—in size. They are bacterial infections. Rat and bird mites are very small, a very diverse group of arthropods that can be found in approximately the size of the period at the end of this just about any habitat. Mites are scavengers, predators, sentence. They are quite active and will enter the living or parasites of plants, insects and animals. Some mites areas of a home when their hosts (rats or birds) have left can transmit diseases, cause agricultural losses, affect or have died. Heavy infestations may cause some mites honeybee colonies, or cause dermatitis and allergies in to search for additional blood meals. Unfed females may humans. Although mites such as mold mites go unnoticed live ten days or more after rats have been eliminated. In and have no direct effect on humans, they can become a this area, tropical rat mites are normally associated with nuisance due to their large numbers. Other mites known the roof rat (Rattus rattus), but are also occasionally found to cause a red itchy rash (known as contact dermatitis) on the Norway rat, (R. norvegicus) and house mouse (Mus include a variety of grain and mold mites. Some species musculus). -

A Phylogeographic Survey of the Pygmy Mouse Mus Minutoides in South Africa: Taxonomic and Karyotypic Inference from Cytochrome B Sequences of Museum Specimens

A Phylogeographic Survey of the Pygmy Mouse Mus minutoides in South Africa: Taxonomic and Karyotypic Inference from Cytochrome b Sequences of Museum Specimens Pascale Chevret1*, Terence J. Robinson2, Julie Perez3, Fre´de´ric Veyrunes3, Janice Britton-Davidian3 1 Laboratoire de Biome´trie et Biologie Evolutive, UMR CNRS 5558, Universite´ Lyon 1, Villeurbanne, France, 2 Evolutionary Genomics Group, Department of Botany and Zoology, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 3 Institut des Sciences de l’Evolution de Montpellier, UMR CNRS 5554, Universite´ Montpellier 2, Montpellier, France Abstract The African pygmy mice (Mus, subgenus Nannomys) are a group of small-sized rodents that occur widely throughout sub- Saharan Africa. Chromosomal diversity within this group is extensive and numerous studies have shown the karyotype to be a useful taxonomic marker. This is pertinent to Mus minutoides populations in South Africa where two different cytotypes (2n = 34, 2n = 18) and a modification of the sex determination system (due to the presence of a Y chromosome in some females) have been recorded. This chromosomal diversity is mirrored by mitochondrial DNA sequences that unambiguously discriminate among the various pygmy mouse species and, importantly, the different M. minutoides cytotypes. However, the geographic delimitation and taxonomy of pygmy mice populations in South Africa is poorly understood. To address this, tissue samples of M. minutoides were taken and analysed from specimens housed in six South African museum collections. Partial cytochrome b sequences (400 pb) were successfully amplified from 44% of the 154 samples processed. Two species were identified: M. indutus and M. minutoides. The sequences of the M. indutus samples provided two unexpected features: i) nuclear copies of the cytochrome b gene were detected in many specimens, and ii) the range of this species was found to extend considerably further south than is presently understood. -

Rats and Mice Have Always Posed a Threat to Human Health

Rats and mice have always posed a threat to human health. Not only do they spread disease but they also cause serious damage to human food and animal feed as well as to buildings, insulation material and electricity cabling. Rats and mice - unwanted house guests! RATS AND MICE ARE AGILE MAMMALS. A mouse can get through a small, 6-7 mm hole (about the diameter of a normal-sized pen) and a rat can get through a 20 mm hole. They can also jump several decimetres at a time. They have no problem climbing up the inside of a vertical sewage pipe and can fall several metres without injuring themselves. Rats are also good swimmers and can be underwater for 5 minutes. IN SWEDEN THERE ARE BASICALLY four different types of rodent that affect us as humans and our housing: the brown rat, the house mouse and the small and large field mouse. THE BROWN RAT (RATTUS NORVEGICUS) THRIVES in all human environments, and especially in damp environments like cellars and sewers. The brown rat is between 20-30 cm in length not counting its tail, which is about 15-23 cm long. These rats normally have brown backs and grey underbellies, but there are also darker ones. They are primarily nocturnal, often keep together in large family groups and dig and gnaw out extensive tunnel systems. Inside these systems, they build large chambers where they store food and build their nests. A pair of rats can produce between 800 and 1000 offspring a year. Since their young are sexually mature and can have offspring of their own at just 2-4 months old, rats reproduce extraordinarily quickly. -

A Haplotype Map for the Laboratory Mouse

NEWS AND VIEWS Sample size dictates inference dogma collection, rather than to data generation or ent experimental approaches provides insight The technical revolution that made the cur- analysis. The open question is whether the com- into mechanism and helps specify the genetic rent data boom possible has matured; genetics munity of funding agencies, peer reviewers and model. In fact, genomic convergence is a spe- laboratories now routinely generate millions of regulatory bodies will be prepared to encourage cific embodiment of the concept of ‘consilience genotypes per day. However, more data can be a and support the assembly of subjects and mate- of inductions’, formulated by William Whewell problem when we do not have the discipline to rials needed to accomplish these goals. in the 1840s11, which says that valid inductions apply the scientific method. Replication is also will be supported by data from many different a problem when working with effects so small Candidate gene success experimental approaches. that replication success could not be reasonably Rather than being discovered initially through a Although they benefit greatly from the expected, even if the marker is associated with genome-wide scan of hundreds of thousands of impressive acceleration provided by genome- the disease. genetic markers, which is now the rage, IL7R is wide scans, virtually all genetic association Larger sample size is the mantra of the hour. a candidate gene that refused to quit. Certainly, disease studies ultimately become candidate Experimentalists and funding agencies no longer the first paper on IL7R polymorphisms in mul- gene projects. Additional susceptibility genes in scoff at theoretical analyses showing that thou- tiple sclerosis7 would not have satisfied the strin- multiple sclerosis—siblings of HLA-DRB2, IL7R sands of cases and controls are needed to dem- gent replication criteria advocated by a recent and, probably, IL2RA4—might now stand above onstrate modest genetic associations (Fig. -

Enrichment for Laboratory Zebrafish—A Review of the Evidence and the Challenges

animals Review Enrichment for Laboratory Zebrafish—A Review of the Evidence and the Challenges Chloe H. Stevens *, Barney T. Reed and Penny Hawkins Animals in Science Department, RSPCA, Wilberforce Way, Southwater, West Sussex RH13 9RS, UK; [email protected] (B.T.R.); [email protected] (P.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: The zebrafish is one of the most commonly used animals in scientific research, but there remains a lack of consensus over good practice for zebrafish housing and care. One such area which lacks agreement is whether laboratory zebrafish should be provided with environmental enrichment—additions or modifications to the basic laboratory environment which aim to improve welfare, such as plastic plants in tanks. The need for the provision of appropriate environmental enrichment has been recognised in other laboratory animal species, but some scientists and animal care staff are hesitant to provide enrichment for zebrafish, arguing that there is little or no evidence that enrichment can benefit zebrafish welfare. This review aims to summarise the current literature on the effects of enrichment on zebrafish physiology, behaviour and welfare, and identifies some forms of enrichment which are likely to benefit zebrafish. It also considers the possible challenges that might be associated with introducing more enrichment, and how these might be addressed. Abstract: Good practice for the housing and care of laboratory zebrafish Danio rerio is an increasingly discussed topic, with focus on appropriate water quality parameters, stocking densities, feeding Citation: Stevens, C.H.; Reed, B.T.; regimes, anaesthesia and analgesia practices, methods of humane killing, and more. -

Genetic Analysis of Complex Traits in the Emerging Collaborative Cross

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 5, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research Genetic analysis of complex traits in the emerging Collaborative Cross David L. Aylor,1 William Valdar,1,13 Wendy Foulds-Mathes,1,13 Ryan J. Buus,1,13 Ricardo A. Verdugo,2,13 Ralph S. Baric,3,4 Martin T. Ferris,1 Jeff A. Frelinger,4 Mark Heise,1 Matt B. Frieman,4 Lisa E. Gralinski,4 Timothy A. Bell,1 John D. Didion,1 Kunjie Hua,1 Derrick L. Nehrenberg,1 Christine L. Powell,1 Jill Steigerwalt,5 Yuying Xie,1 Samir N.P. Kelada,6 Francis S. Collins,6 Ivana V. Yang,7 David A. Schwartz,7 Lisa A. Branstetter,8 Elissa J. Chesler,2 Darla R. Miller,1 Jason Spence,1 Eric Yi Liu,9 Leonard McMillan,9 Abhishek Sarkar,9 Jeremy Wang,9 Wei Wang,9 Qi Zhang,9 Karl W. Broman,10 Ron Korstanje,2 Caroline Durrant,11 Richard Mott,11 Fuad A. Iraqi,12 Daniel Pomp,1,14 David Threadgill,5,14 Fernando Pardo-Manuel de Villena,1,14 and Gary A. Churchill2,14 1Department of Genetics, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, USA; 2The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine 04609, USA; 3Department of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, USA; 4Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, USA; 5Department of Genetics, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27695, USA; 6Genome Technology Branch, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland -

Mice Are Here to Stay

Mice A re Here to Stay Wherever people live, there are mice. It would be difficult to find another animal that has adapted to the habitats created by humans as well as the house mouse has. It thus seemed obvious to Diethard Tautz at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Plön that the species would make an ideal model system for investigating how evolution works. BIOLOGY & MEDICINE_Evolution Mice A re Here to Stay TEXT CORNELIA STOLZE he mice at the Max Planck mice themselves only within a range of can be a key factor in the emergence of Institute in Plön live in their 30 to 50 centimeters, they convey high- new species. For Tautz, the house very own house: they have ly complex messages. mouse is a model for the processes of 16 rooms where they can Diethard Tautz and his colleagues evolution: it would be difficult to find form their family clans and have discovered that house mice be- another animal species that lends itself T territories as they see fit. The experi- have naturally only when they live in so well to the study of the genetic ments Tautz and his colleagues carry a familiar environment and interact mechanisms of evolution. out to study such facets as the rodents’ with other members of their species. “Not only is this species extremely communication, behavior and partner- When animals living in the wild are adaptable, as demonstrated by its dis- ships sometimes take months. During captured, they lose their familiar envi- persal all over the globe, but we also this time, the mice are largely left to ronment: everything smells and tastes know its genome better than that of al- their own devices. -

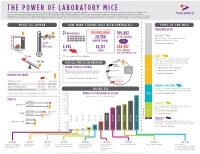

THE POWER of LABORATORY MICE Since the First Published Study Using Mice in 1844, Over 1.4 Million Scholarly Articles Have Been Published

THE POWER OF LABORATORY MICE Since the first published study using mice in 1844, over 1.4 million scholarly articles have been published. Over half of those articles have been published in the past 2 decades and twice as many were published in the decade 2007—2016 than 1997—2006. These data demonstrate the increasing value of laboratory mice in biomedical research. Genetically engineered mice bolstered this growth by improving the ability to translate results to humans. Looking forward, the laboratory mouse will continue to play a critical role in biomedical research, as the ability to generate increasingly precise models will give the researcher of tomorrow an animal that has power to further our understanding of complex human biology. MOUSE VS. HUMAN = HOW MANY STRAINS HAVE BEEN GENERATED? TYPES OF LAB MICE 70 37 °C PERCENTAGE OF USE = 21 REPOSITORIES CRYOPRESERVED 199,892 AVERAGE = = OUTBRED 70 BODY 20,390 ES CELL STRAINS 70 70 37 °C37 °C37 °C 38% Production of offspring from mating of unrelated individuals. TEMPERATURE EMBRYO STRAINS Outbred breeding maintains genetic diversity. AVERAGE LIFE SPAN 1.5 AVERAGE AVERAGE AVERAGE Learn more about outbred mice NUMBER OF BODY BODY BODY YEARS TEMPERATURE AVERAGE LIFE SPAN 1.5 TEMPERATURETEMPERATURE IN VITRO AVERAGE LIFE SPAN AVERAGE LIFE SPAN 1.5 1.5 3,955 26,172 236,927 NUMBER OF NUMBER NUMBEROF OF YEARS LIVE SPERM TOTAL ENTRIES 20 grYEARS YEARS (LIVE, SPERM, EMBRYO, ES CELL) 20 gr20 gr20 gr Source: International Mouse Strain Repository INBRED AVERAGE WEIGHT Production of offspring from mating of male and female mice that are 68AVERAGE kg WEIGHT AVERAGE WEIGHTAVERAGE WEIGHT 68 kg closely related genetically, typically brother x sister mating.