Genetic Analysis of Complex Traits in the Emerging Collaborative Cross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpreting Noncoding Genetic Variation in Complex Traits and Human Disease

REVIEW Interpreting noncoding genetic variation in complex traits and human disease Lucas D Ward1,2 & Manolis Kellis1,2 Association studies provide genome-wide information about the genetic basis of complex disease, but medical research has focused primarily on protein-coding variants, owing to the difficulty of interpreting noncoding mutations. This picture has changed with advances in the systematic annotation of functional noncoding elements. Evolutionary conservation, functional genomics, chromatin state, sequence motifs and molecular quantitative trait loci all provide complementary information about the function of noncoding sequences. These functional maps can help with prioritizing variants on risk haplotypes, filtering mutations encountered in the clinic and performing systems-level analyses to reveal processes underlying disease associations. Advances in predictive modeling can enable data-set integration to reveal pathways shared across loci and alleles, and richer regulatory models can guide the search for epistatic interactions. Lastly, new massively parallel reporter experiments can systematically validate regulatory predictions. Ultimately, advances in regulatory and systems genomics can help unleash the value of whole-genome sequencing for personalized genomic risk assessment, diagnosis and treatment. Understanding the genetic basis of disease can transform medicine ture of the human genome, and its systematic mapping by the HapMap by elucidating relevant biochemical pathways for drug targets and by Project9, allowed single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to be used enabling personalized risk assessments1,2. With the evolution of technol- as markers for common haplotypes, which could be genotyped using ogies over the past century, geneticists are no longer limited to studying chip technology. The stage was set for a flood of unbiased, genome-wide Mendelian disorders and can tackle complex phenotypes. -

Mouse Models of Human Disease an Evolutionary Perspective Robert L

170 commentary Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health [2016] pp. 170–176 doi:10.1093/emph/eow014 Mouse models of human disease An evolutionary perspective Robert L. Perlman* Department of Pediatrics, The University of Chicago, 5841 S. Maryland Ave, MC 5058, Chicago, IL 60637, USA *E-mail: [email protected] Received 31 December 2015; revised version accepted 12 April 2016 ABSTRACT The use of mice as model organisms to study human biology is predicated on the genetic and physio- logical similarities between the species. Nonetheless, mice and humans have evolved in and become adapted to different environments and so, despite their phylogenetic relatedness, they have become very different organisms. Mice often respond to experimental interventions in ways that differ strikingly from humans. Mice are invaluable for studying biological processes that have been conserved during the evolution of the rodent and primate lineages and for investigating the developmental mechanisms by which the conserved mammalian genome gives rise to a variety of different species. Mice are less reliable as models of human disease, however, because the networks linking genes to disease are likely to differ between the two species. The use of mice in biomedical research needs to take account of the evolved differences as well as the similarities between mice and humans. KEYWORDS: allometry; cancer; gene networks; life history; model organisms transgenic, knockout, and knockin mice, have If you have cancer and you are a mouse, we can provided added impetus and powerful tools for take good care of you. Judah Folkman [1] mouse research, and have led to a dramatic increase in the use of mice as model organisms. -

Genetics in Harry Potter's World: Lesson 2

Genetics in Harry Potter’s World Lesson 2 • Beyond Mendelian Inheritance • Genetics of Magical Ability 1 Rules of Inheritance • Some traits follow the simple rules of Mendelian inheritance of dominant and recessive genes. • Complex traits follow different patterns of inheritance that may involve multiples genes and other factors. For example, – Incomplete or blended dominance – Codominance – Multiple alleles – Regulatory genes Any guesses on what these terms may mean? 2 Incomplete Dominance • Incomplete dominance results in a phenotype that is a blend of a heterozygous allele pair. Ex., Red flower + Blue flower => Purple flower • If the dragons in Harry Potter have fire-power alleles F (strong fire) and F’ (no fire) that follow incomplete dominance, what are the phenotypes for the following dragon-fire genotypes? – FF – FF’ – F’F’ 3 Incomplete Dominance • Incomplete dominance results in a phenotype that is a blend of the two traits in an allele pair. Ex., Red flower + Blue flower => Purple flower • If the Dragons in Harry Potter have fire-power alleles F (strong fire) and F’ (no fire) that follow incomplete dominance, what are the phenotypes for the following dragon-fire genotypes: Genotypes Phenotypes FF strong fire FF’ moderate fire (blended trait) F’F’ no fire 4 Codominance • Codominance results in a phenotype that shows both traits of an allele pair. Ex., Red flower + White flower => Red & White spotted flower • If merpeople have tail color alleles B (blue) and G (green) that follow the codominance inheritance rule, what are possible genotypes and phenotypes? Genotypes Phenotypes 5 Codominance • Codominance results in a phenotype that shows both traits of an allele pair. -

The Genetics of Complex Traits Programme Course 7.5 Credits Genetiska Mekanismer Bakom Komplexa Egenskaper 8MEA14 Valid From: 2019 Autumn Semester

DNR LIU-2019-00662 1(5) The genetics of complex traits Programme course 7.5 credits Genetiska mekanismer bakom komplexa egenskaper 8MEA14 Valid from: 2019 Autumn semester Determined by The Board for First and Second Cycle Programmes at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Date determined 2019-03-07 LINKÖPING UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF MEDICINE AND HEALTH SCIENCES LINKÖPING UNIVERSITY THE GENETICS OF COMPLEX TRAITS FACULTY OF MEDICINE AND HEALTH SCIENCES 2(5) Main field of study Medical Biology Course level Second cycle Advancement level A1X Course offered for Master's Programme in Experimental and Medical Biosciences Entry requirements Degree of Bachelor of Science, 180 ECTS in a major subject area such as medicine, biology, technology/natural sciences, odontology or veterinary medicine. 90 ECTS of courses included in the Bachelor degree should be in subjects such as biochemistry, cell biology, molecular biology, genetics, gene technology, microbiology, immunology, physiology, histology, anatomy or pathology. Documented skills in English corresponding to level 6/B. Intended learning outcomes The student will learn and understand the basis of quantitative genetic techniques, in particular how they pertain to the identification of genes underlying complex traits and diseases. Knowledge and understanding On completion of the course, the student shall be able to: Describe and understand statistical quantitative genetic techniques and how they apply to complex traits. Explain the statistical basis of quantitative traits. Explain and distinguish between linkage and linkage disequilibrium and their uses. Analyse the genetic architecture of different behavioral and disease-related traits. Analyse and understand the theory and steps required to identify the genetic components of a quantitative trait. -

Laboratory Animal Management: Rodents

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/2119 SHARE Rodents (1996) DETAILS 180 pages | 6 x 9 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-04936-8 | DOI 10.17226/2119 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Committee on Rodents, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council FIND RELATED TITLES SUGGESTED CITATION National Research Council 1996. Rodents. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/2119. Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Rodents i Laboratory Animal Management Rodents Committee on Rodents Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources Commission on Life Sciences National Research Council NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS Washington, D.C.1996 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Rodents ii National Academy Press 2101 Constitution Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20418 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. -

Subterranean Mammals Show Convergent Regression in Ocular Genes and Enhancers, Along with Adaptation to Tunneling

RESEARCH ARTICLE Subterranean mammals show convergent regression in ocular genes and enhancers, along with adaptation to tunneling Raghavendran Partha1, Bharesh K Chauhan2,3, Zelia Ferreira1, Joseph D Robinson4, Kira Lathrop2,3, Ken K Nischal2,3, Maria Chikina1*, Nathan L Clark1* 1Department of Computational and Systems Biology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, United States; 2UPMC Eye Center, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, United States; 3Department of Ophthalmology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, United States; 4Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California, Berkeley, United States Abstract The underground environment imposes unique demands on life that have led subterranean species to evolve specialized traits, many of which evolved convergently. We studied convergence in evolutionary rate in subterranean mammals in order to associate phenotypic evolution with specific genetic regions. We identified a strong excess of vision- and skin-related genes that changed at accelerated rates in the subterranean environment due to relaxed constraint and adaptive evolution. We also demonstrate that ocular-specific transcriptional enhancers were convergently accelerated, whereas enhancers active outside the eye were not. Furthermore, several uncharacterized genes and regulatory sequences demonstrated convergence and thus constitute novel candidate sequences for congenital ocular disorders. The strong evidence of convergence in these species indicates that evolution in this environment is recurrent and predictable and can be used to gain insights into phenotype–genotype relationships. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.25884.001 *For correspondence: [email protected] (MC); [email protected] (NLC) Competing interests: The Introduction authors declare that no The subterranean habitat has been colonized by numerous animal species for its shelter and unique competing interests exist. -

A Haplotype Map for the Laboratory Mouse

NEWS AND VIEWS Sample size dictates inference dogma collection, rather than to data generation or ent experimental approaches provides insight The technical revolution that made the cur- analysis. The open question is whether the com- into mechanism and helps specify the genetic rent data boom possible has matured; genetics munity of funding agencies, peer reviewers and model. In fact, genomic convergence is a spe- laboratories now routinely generate millions of regulatory bodies will be prepared to encourage cific embodiment of the concept of ‘consilience genotypes per day. However, more data can be a and support the assembly of subjects and mate- of inductions’, formulated by William Whewell problem when we do not have the discipline to rials needed to accomplish these goals. in the 1840s11, which says that valid inductions apply the scientific method. Replication is also will be supported by data from many different a problem when working with effects so small Candidate gene success experimental approaches. that replication success could not be reasonably Rather than being discovered initially through a Although they benefit greatly from the expected, even if the marker is associated with genome-wide scan of hundreds of thousands of impressive acceleration provided by genome- the disease. genetic markers, which is now the rage, IL7R is wide scans, virtually all genetic association Larger sample size is the mantra of the hour. a candidate gene that refused to quit. Certainly, disease studies ultimately become candidate Experimentalists and funding agencies no longer the first paper on IL7R polymorphisms in mul- gene projects. Additional susceptibility genes in scoff at theoretical analyses showing that thou- tiple sclerosis7 would not have satisfied the strin- multiple sclerosis—siblings of HLA-DRB2, IL7R sands of cases and controls are needed to dem- gent replication criteria advocated by a recent and, probably, IL2RA4—might now stand above onstrate modest genetic associations (Fig. -

Enrichment for Laboratory Zebrafish—A Review of the Evidence and the Challenges

animals Review Enrichment for Laboratory Zebrafish—A Review of the Evidence and the Challenges Chloe H. Stevens *, Barney T. Reed and Penny Hawkins Animals in Science Department, RSPCA, Wilberforce Way, Southwater, West Sussex RH13 9RS, UK; [email protected] (B.T.R.); [email protected] (P.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: The zebrafish is one of the most commonly used animals in scientific research, but there remains a lack of consensus over good practice for zebrafish housing and care. One such area which lacks agreement is whether laboratory zebrafish should be provided with environmental enrichment—additions or modifications to the basic laboratory environment which aim to improve welfare, such as plastic plants in tanks. The need for the provision of appropriate environmental enrichment has been recognised in other laboratory animal species, but some scientists and animal care staff are hesitant to provide enrichment for zebrafish, arguing that there is little or no evidence that enrichment can benefit zebrafish welfare. This review aims to summarise the current literature on the effects of enrichment on zebrafish physiology, behaviour and welfare, and identifies some forms of enrichment which are likely to benefit zebrafish. It also considers the possible challenges that might be associated with introducing more enrichment, and how these might be addressed. Abstract: Good practice for the housing and care of laboratory zebrafish Danio rerio is an increasingly discussed topic, with focus on appropriate water quality parameters, stocking densities, feeding Citation: Stevens, C.H.; Reed, B.T.; regimes, anaesthesia and analgesia practices, methods of humane killing, and more. -

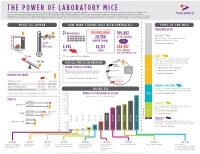

THE POWER of LABORATORY MICE Since the First Published Study Using Mice in 1844, Over 1.4 Million Scholarly Articles Have Been Published

THE POWER OF LABORATORY MICE Since the first published study using mice in 1844, over 1.4 million scholarly articles have been published. Over half of those articles have been published in the past 2 decades and twice as many were published in the decade 2007—2016 than 1997—2006. These data demonstrate the increasing value of laboratory mice in biomedical research. Genetically engineered mice bolstered this growth by improving the ability to translate results to humans. Looking forward, the laboratory mouse will continue to play a critical role in biomedical research, as the ability to generate increasingly precise models will give the researcher of tomorrow an animal that has power to further our understanding of complex human biology. MOUSE VS. HUMAN = HOW MANY STRAINS HAVE BEEN GENERATED? TYPES OF LAB MICE 70 37 °C PERCENTAGE OF USE = 21 REPOSITORIES CRYOPRESERVED 199,892 AVERAGE = = OUTBRED 70 BODY 20,390 ES CELL STRAINS 70 70 37 °C37 °C37 °C 38% Production of offspring from mating of unrelated individuals. TEMPERATURE EMBRYO STRAINS Outbred breeding maintains genetic diversity. AVERAGE LIFE SPAN 1.5 AVERAGE AVERAGE AVERAGE Learn more about outbred mice NUMBER OF BODY BODY BODY YEARS TEMPERATURE AVERAGE LIFE SPAN 1.5 TEMPERATURETEMPERATURE IN VITRO AVERAGE LIFE SPAN AVERAGE LIFE SPAN 1.5 1.5 3,955 26,172 236,927 NUMBER OF NUMBER NUMBEROF OF YEARS LIVE SPERM TOTAL ENTRIES 20 grYEARS YEARS (LIVE, SPERM, EMBRYO, ES CELL) 20 gr20 gr20 gr Source: International Mouse Strain Repository INBRED AVERAGE WEIGHT Production of offspring from mating of male and female mice that are 68AVERAGE kg WEIGHT AVERAGE WEIGHTAVERAGE WEIGHT 68 kg closely related genetically, typically brother x sister mating. -

Reference Trait Analysis Reveals Correlations Between Gene Expression and Quantitative Traits in Disjoint Samples

HIGHLIGHTED ARTICLE | INVESTIGATION Reference Trait Analysis Reveals Correlations Between Gene Expression and Quantitative Traits in Disjoint Samples Daniel A. Skelly,* Narayanan Raghupathy,* Raymond F. Robledo,* Joel H. Graber,*,† and Elissa J. Chesler*,1 *The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine 04609 and †MDI Biological Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine 04609 ORCID IDs: 0000-0002-2329-2216 (D.A.S.); 0000-0002-5642-5062 (E.J.C.) ABSTRACT Systems genetic analysis of complex traits involves the integrated analysis of genetic, genomic, and disease-related measures. However, these data are often collected separately across multiple study populations, rendering direct correlation of molecular features to complex traits impossible. Recent transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) have harnessed gene expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) to associate unmeasured gene expression with a complex trait in genotyped individuals, but this approach relies primarily on strong eQTL. We propose a simple and powerful alternative strategy for correlating independently obtained sets of complex traits and molecular features. In contrast to TWAS, our approach gains precision by correlating complex traits through a common set of continuous phenotypes instead of genetic predictors, and can identify transcript–trait correlations for which the regulation is not genetic. In our approach, a set of multiple quantitative “reference” traits is measured across all individuals, while measures of the complex trait of interest and transcriptional profiles are obtained in disjoint subsamples. A conventional multivariate statistical method, canonical correlation analysis, is used to relate the reference traits and traits of interest to identify gene expression correlates. We evaluate power and sample size requirements of this methodology, as well as performance relative to other methods, via extensive simulation and analysis of a behavioral genetics experiment in 258 Diversity Outbred mice involving two independent sets of anxiety-related behaviors and hippocampal gene expression. -

Genetics and Human Traits

Help Me Understand Genetics Genetics and Human Traits Reprinted from MedlinePlus Genetics U.S. National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health Department of Health & Human Services Table of Contents 1 Are fingerprints determined by genetics? 1 2 Is eye color determined by genetics? 3 3 Is intelligence determined by genetics? 5 4 Is handedness determined by genetics? 7 5 Is the probability of having twins determined by genetics? 9 6 Is hair texture determined by genetics? 11 7 Is hair color determined by genetics? 13 8 Is height determined by genetics? 16 9 Are moles determined by genetics? 18 10 Are facial dimples determined by genetics? 20 11 Is athletic performance determined by genetics? 21 12 Is longevity determined by genetics? 23 13 Is temperament determined by genetics? 26 Reprinted from MedlinePlus Genetics (https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/) i Genetics and Human Traits 1 Are fingerprints determined by genetics? Each person’s fingerprints are unique, which is why they have long been used as a way to identify individuals. Surprisingly little is known about the factors that influence a person’s fingerprint patterns. Like many other complex traits, studies suggest that both genetic and environmental factors play a role. A person’s fingerprints are based on the patterns of skin ridges (called dermatoglyphs) on the pads of the fingers. These ridges are also present on the toes, the palms of the hands, and the soles of the feet. Although the basic whorl, arch, and loop patterns may be similar, the details of the patterns are specific to each individual. Dermatoglyphs develop before birth and remain the same throughout life. -

15141 POMP (D2X9S) Rabbit Mab

Revision 1 C 0 2 - t POMP (D2X9S) Rabbit mAb a e r o t S Orders: 877-616-CELL (2355) [email protected] 1 Support: 877-678-TECH (8324) 4 1 Web: [email protected] 5 www.cellsignal.com 1 # 3 Trask Lane Danvers Massachusetts 01923 USA For Research Use Only. Not For Use In Diagnostic Procedures. Applications: Reactivity: Sensitivity: MW (kDa): Source/Isotype: UniProt ID: Entrez-Gene Id: WB, IP H M R Mk Endogenous 16 Rabbit IgG Q9Y244 51371 Product Usage Information immunoproteasomes, and that the assembly focal point resides at the endoplasmic reticulum (6-8). A single nucleotide deletion in the 5' UTR of POMP results in altered Application Dilution epidermal POMP distribution and the autosomal recessive skin disorder known as KLICK syndrome (9). Western Blotting 1:1000 1. Finley, D. (2009) Annu Rev Biochem 78, 477-513. Immunoprecipitation 1:200 2. Lee, M.J. et al. (2011) Mol Cell Proteomics 10, R110.003871. 3. Griffin, T.A. et al. (2000) Mol Cell Biol Res Commun 3, 212-7. 4. Witt, E. et al. (2000) J Mol Biol 301, 1-9. Storage 5. Ramos, P.C. et al. (1998) Cell 92, 489-99. Supplied in 10 mM sodium HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 100 µg/ml BSA, 50% 6. Fricke, B. et al. (2007) EMBO Rep 8, 1170-5. glycerol and less than 0.02% sodium azide. Store at –20°C. Do not aliquot the antibody. 7. Heink, S. et al. (2005) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 9241-6. 8. Heink, S.