Interpreting Noncoding Genetic Variation in Complex Traits and Human Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetics in Harry Potter's World: Lesson 2

Genetics in Harry Potter’s World Lesson 2 • Beyond Mendelian Inheritance • Genetics of Magical Ability 1 Rules of Inheritance • Some traits follow the simple rules of Mendelian inheritance of dominant and recessive genes. • Complex traits follow different patterns of inheritance that may involve multiples genes and other factors. For example, – Incomplete or blended dominance – Codominance – Multiple alleles – Regulatory genes Any guesses on what these terms may mean? 2 Incomplete Dominance • Incomplete dominance results in a phenotype that is a blend of a heterozygous allele pair. Ex., Red flower + Blue flower => Purple flower • If the dragons in Harry Potter have fire-power alleles F (strong fire) and F’ (no fire) that follow incomplete dominance, what are the phenotypes for the following dragon-fire genotypes? – FF – FF’ – F’F’ 3 Incomplete Dominance • Incomplete dominance results in a phenotype that is a blend of the two traits in an allele pair. Ex., Red flower + Blue flower => Purple flower • If the Dragons in Harry Potter have fire-power alleles F (strong fire) and F’ (no fire) that follow incomplete dominance, what are the phenotypes for the following dragon-fire genotypes: Genotypes Phenotypes FF strong fire FF’ moderate fire (blended trait) F’F’ no fire 4 Codominance • Codominance results in a phenotype that shows both traits of an allele pair. Ex., Red flower + White flower => Red & White spotted flower • If merpeople have tail color alleles B (blue) and G (green) that follow the codominance inheritance rule, what are possible genotypes and phenotypes? Genotypes Phenotypes 5 Codominance • Codominance results in a phenotype that shows both traits of an allele pair. -

The Genetics of Complex Traits Programme Course 7.5 Credits Genetiska Mekanismer Bakom Komplexa Egenskaper 8MEA14 Valid From: 2019 Autumn Semester

DNR LIU-2019-00662 1(5) The genetics of complex traits Programme course 7.5 credits Genetiska mekanismer bakom komplexa egenskaper 8MEA14 Valid from: 2019 Autumn semester Determined by The Board for First and Second Cycle Programmes at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Date determined 2019-03-07 LINKÖPING UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF MEDICINE AND HEALTH SCIENCES LINKÖPING UNIVERSITY THE GENETICS OF COMPLEX TRAITS FACULTY OF MEDICINE AND HEALTH SCIENCES 2(5) Main field of study Medical Biology Course level Second cycle Advancement level A1X Course offered for Master's Programme in Experimental and Medical Biosciences Entry requirements Degree of Bachelor of Science, 180 ECTS in a major subject area such as medicine, biology, technology/natural sciences, odontology or veterinary medicine. 90 ECTS of courses included in the Bachelor degree should be in subjects such as biochemistry, cell biology, molecular biology, genetics, gene technology, microbiology, immunology, physiology, histology, anatomy or pathology. Documented skills in English corresponding to level 6/B. Intended learning outcomes The student will learn and understand the basis of quantitative genetic techniques, in particular how they pertain to the identification of genes underlying complex traits and diseases. Knowledge and understanding On completion of the course, the student shall be able to: Describe and understand statistical quantitative genetic techniques and how they apply to complex traits. Explain the statistical basis of quantitative traits. Explain and distinguish between linkage and linkage disequilibrium and their uses. Analyse the genetic architecture of different behavioral and disease-related traits. Analyse and understand the theory and steps required to identify the genetic components of a quantitative trait. -

Genetic Analysis of Complex Traits in the Emerging Collaborative Cross

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 5, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research Genetic analysis of complex traits in the emerging Collaborative Cross David L. Aylor,1 William Valdar,1,13 Wendy Foulds-Mathes,1,13 Ryan J. Buus,1,13 Ricardo A. Verdugo,2,13 Ralph S. Baric,3,4 Martin T. Ferris,1 Jeff A. Frelinger,4 Mark Heise,1 Matt B. Frieman,4 Lisa E. Gralinski,4 Timothy A. Bell,1 John D. Didion,1 Kunjie Hua,1 Derrick L. Nehrenberg,1 Christine L. Powell,1 Jill Steigerwalt,5 Yuying Xie,1 Samir N.P. Kelada,6 Francis S. Collins,6 Ivana V. Yang,7 David A. Schwartz,7 Lisa A. Branstetter,8 Elissa J. Chesler,2 Darla R. Miller,1 Jason Spence,1 Eric Yi Liu,9 Leonard McMillan,9 Abhishek Sarkar,9 Jeremy Wang,9 Wei Wang,9 Qi Zhang,9 Karl W. Broman,10 Ron Korstanje,2 Caroline Durrant,11 Richard Mott,11 Fuad A. Iraqi,12 Daniel Pomp,1,14 David Threadgill,5,14 Fernando Pardo-Manuel de Villena,1,14 and Gary A. Churchill2,14 1Department of Genetics, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, USA; 2The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine 04609, USA; 3Department of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, USA; 4Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, USA; 5Department of Genetics, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27695, USA; 6Genome Technology Branch, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland -

Reference Trait Analysis Reveals Correlations Between Gene Expression and Quantitative Traits in Disjoint Samples

HIGHLIGHTED ARTICLE | INVESTIGATION Reference Trait Analysis Reveals Correlations Between Gene Expression and Quantitative Traits in Disjoint Samples Daniel A. Skelly,* Narayanan Raghupathy,* Raymond F. Robledo,* Joel H. Graber,*,† and Elissa J. Chesler*,1 *The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine 04609 and †MDI Biological Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine 04609 ORCID IDs: 0000-0002-2329-2216 (D.A.S.); 0000-0002-5642-5062 (E.J.C.) ABSTRACT Systems genetic analysis of complex traits involves the integrated analysis of genetic, genomic, and disease-related measures. However, these data are often collected separately across multiple study populations, rendering direct correlation of molecular features to complex traits impossible. Recent transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) have harnessed gene expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) to associate unmeasured gene expression with a complex trait in genotyped individuals, but this approach relies primarily on strong eQTL. We propose a simple and powerful alternative strategy for correlating independently obtained sets of complex traits and molecular features. In contrast to TWAS, our approach gains precision by correlating complex traits through a common set of continuous phenotypes instead of genetic predictors, and can identify transcript–trait correlations for which the regulation is not genetic. In our approach, a set of multiple quantitative “reference” traits is measured across all individuals, while measures of the complex trait of interest and transcriptional profiles are obtained in disjoint subsamples. A conventional multivariate statistical method, canonical correlation analysis, is used to relate the reference traits and traits of interest to identify gene expression correlates. We evaluate power and sample size requirements of this methodology, as well as performance relative to other methods, via extensive simulation and analysis of a behavioral genetics experiment in 258 Diversity Outbred mice involving two independent sets of anxiety-related behaviors and hippocampal gene expression. -

Genetics and Human Traits

Help Me Understand Genetics Genetics and Human Traits Reprinted from MedlinePlus Genetics U.S. National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health Department of Health & Human Services Table of Contents 1 Are fingerprints determined by genetics? 1 2 Is eye color determined by genetics? 3 3 Is intelligence determined by genetics? 5 4 Is handedness determined by genetics? 7 5 Is the probability of having twins determined by genetics? 9 6 Is hair texture determined by genetics? 11 7 Is hair color determined by genetics? 13 8 Is height determined by genetics? 16 9 Are moles determined by genetics? 18 10 Are facial dimples determined by genetics? 20 11 Is athletic performance determined by genetics? 21 12 Is longevity determined by genetics? 23 13 Is temperament determined by genetics? 26 Reprinted from MedlinePlus Genetics (https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/) i Genetics and Human Traits 1 Are fingerprints determined by genetics? Each person’s fingerprints are unique, which is why they have long been used as a way to identify individuals. Surprisingly little is known about the factors that influence a person’s fingerprint patterns. Like many other complex traits, studies suggest that both genetic and environmental factors play a role. A person’s fingerprints are based on the patterns of skin ridges (called dermatoglyphs) on the pads of the fingers. These ridges are also present on the toes, the palms of the hands, and the soles of the feet. Although the basic whorl, arch, and loop patterns may be similar, the details of the patterns are specific to each individual. Dermatoglyphs develop before birth and remain the same throughout life. -

A Model and Test for Coordinated Polygenic Epistasis in Complex Traits

A model and test for coordinated polygenic epistasis in complex traits Brooke Shepparda,1, Nadav Rappoporta,b,1, Po-Ru Lohc,d, Stephan J. Sandersa, Noah Zaitlena,e,f,1,2, and Andy Dahle,f,g,1,2 aDepartment of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94143; bBakar Computational Health Sciences Institute, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94143; cProgram in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard, Cambridge, MA 02142; dDivision of Genetics, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; eDepartment of Neurology, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095; fDepartment of Computational Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095; and gSection of Genetic Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637 Edited by Andrew G. Clark, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, and approved December 2, 2020 (received for review February 19, 2020) Interactions between genetic variants—epistasis—is pervasive in of epistasis. For example, Zuk et al. describe a limiting pathway model systems and can profoundly impact evolutionary adaption, pop- model of human disease that directly implies negative interactions ulation disease dynamics, genetic mapping, and precision medicine between SNPs contributing to different pathways (29). Also, the efforts. In this work, we develop a model for structured polygenic HSP90 community has discussed the possibility of a polygenic epistasis, called coordinated epistasis (CE), and prove that several re- version of chaperon function (30), which would induce coordi- cent theories of genetic architecture fall under the formal umbrella of nated interactions between HSP90 buffer SNPs and exonic mis- CE. -

Five Fundamental Gaps in Nature-Nurture Science Peter J

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Working Papers on Science in a Changing World Critical and Creative Thinking Program Spring 3-22-2014 Five Fundamental Gaps In Nature-Nurture Science Peter J. Taylor University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_sicw Part of the Biostatistics Commons, and the Genetics Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Peter J., "Five Fundamental Gaps In Nature-Nurture Science" (2014). Working Papers on Science in a Changing World. 3. https://scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_sicw/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Critical and Creative Thinking Program at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Working Papers on Science in a Changing World by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Paper # 3-2014 Five Fundamental Gaps in Nature-Nurture Science PETER J. TAYLOR http://scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_sicw/3 Five Fundamental Gaps In Nature-Nurture Science Peter J. Taylor Science in a Changing World graduate track University of Massachusetts, Boston, MA 02125, USA [email protected] Abstract Difficulties identifying causally relevant genetic variants underlying patterns of human variation have been given competing interpretations. The debate is illuminated in this article by drawing attention to the issue of underlying heterogeneity—the possibility that genetic and environmental factors or -

Inferring Relevant Cell Types for Complex Traits by Integrating Genome-Wide Association Studies and Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.09.447805; this version posted June 23, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. EPIC: inferring relevant cell types for complex traits by integrating genome-wide association studies and single-cell RNA sequencing Rujin Wang1, Dan-Yu Lin1,2, Yuchao Jiang1,2,3,* 1 Department of Biostatistics, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA. 2 Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA. 3 Department of Genetics, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA. To whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected]. bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.09.447805; this version posted June 23, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 Abstract 2 More than a decade of genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified genetic 3 risk variants that are significantly associated with complex traits. Emerging evidence 4 suggests that the function of trait-associated variants likely acts in a tissue- or cell-type- 5 specific fashion. Yet, it remains challenging to prioritize trait-relevant tissues or cell types 6 to elucidate disease etiology. -

8. Pritchardj.Omnigenic Architecture of Human Complex Traits.05012018

Omnigenic architecture of human complex traits Jonathan Pritchard Departments of Genetics & Biology, & HHMI Stanford University Joint work with Evan Boyle, Yang Li, Xuanyao Liu ok Missing Heritability Workshop, NIH,Henry May 2018Stewart Talks Questions: 1. Why do the lead hits for any given trait contribute so little heritability? 2. Why does so much of the genome contribute to heritability? Example #1: Schizophrenia 108 genome-wide significant loci so far (Ripke 2014) Responsible for ~10% of explained variance (Shi…Pasaniuc 2016) We have estimated that ~half of all SNPs -log(p) have non-zero association effect sizes (unpub) chromosome See key work on polygenic models and heritability by Visscher, Yang, Pasaniuc, Price, and many others Example #2: What about a potentially simpler trait: lipid levels? (LDL, HDL and triglycerides) Monogenic lipid disorders ~2 dozen major effect loci Modified from Dron et al 2016 Common Variation: GWAS of Lipid Levels 57 genome-wide significant loci (Willer et al 2013) Monogenic genes for LDL HDL cHolesterol Total cHolesterol The significant loci only explain ~20% of Heritability of LDL All loci togetHer explain about ~80% (SHi…Pasaniuc 2016) Triglycerides LDL cHolesterol Modified from: Willer et al 2013, Dron et al 2016 For a wide variety of traits and diseases: • Heritability is spread extremely widely across the genome • Genes with trait-relevant functions only contribute a small fraction of the total disease risk • Low frequency-large effect variants often have clearer enrichment in relevant gene sets -

Polygenic Prediction of Complex Human Traits Arxiv:2101.05870V1

From Genotype to Phenotype: polygenic prediction of complex human traits Timothy G. Raben1, Louis Lello1,2, Erik Widen1, and Stephen D.H. Hsu1,2 1Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, 48824 2Genomic Prediction, North Brunswick, New Jersey, 08902 Abstract Decoding the genome confers the capability to predict characteristics of the organism (phenotype) from DNA (genotype). We describe the present status and future prospects of genomic prediction of complex traits in humans. Some highly heritable complex phenotypes such as height and other quantitative traits can already be predicted with reasonable accuracy from DNA alone. For many diseases, including important common conditions such as coro- nary artery disease, breast cancer, type I and II diabetes, individuals with outlier polygenic scores (e.g., top few percent) have been shown to have 5 or even 10 times higher risk than average. Several psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia and autism also fall into this arXiv:2101.05870v1 [q-bio.GN] 14 Jan 2021 category. We discuss related topics such as the genetic architecture of complex traits, sibling validation of polygenic scores, and applications to adult health, in vitro fertilization (embryo selection), and genetic engineering. A version of this article was prepared for Genomic Prediction of Complex Traits, Springer Nature book series Methods in Molecular Biology. Keywords: genomics, complex trait prediction, PRS, in vitro fertilization, genetic engineering 1 1 Introduction I, on the other hand, knew nothing, except ... physics and mathematics and an ability to turn my hand to new things. — Francis Crick The challenge of decoding the genome has loomed large over biology since the time of Wat- son and Crick. -

Heritability Jointly Explained by Host Genotype and Microbiome:Will Improve Traits Prediction?

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.25.061226; this version posted April 27, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Heritability jointly Explained by Host Genotype and Microbiome:Will Improve Traits Prediction? Denis Awany 1, and Emile R. Chimusa 1,? 1Division of Human Genetics, Department of Pathology, Institute of Infectious Disease and Molecular Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa. ? Correspondence to Emile R. Chimusa: [email protected] Abstract As we observe the 70th anniversary of the publication by Robertson that formalized the notion of ‘her- itability’, geneticists remain puzzled by the problem of missing/hidden heritability, where heritability estimates from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) fall short of that from twin-based studies. Many possible explanations have been offered for this discrepancy, including existence of genetic vari- ants poorly captured by existing arrays, dominance, epistasis, and unaccounted-for environmental factors; albeit these remain controversial. We believe a substantial part of this problem could be solved or better understood by incorporating the host’s microbiota information in the GWAS model for heritability estimation; ultimately also increasing human traits prediction for clinical utility. This is because, despite empirical observations such as (i) the intimate role of the microbiome in many com- plex human phenotypes, (ii) the overlap between genetic variants associated with both microbiome attributes and complex diseases, and (iii) the existence of heritable bacterial taxa, current GWAS models for heritability estimate do not take into account the contributory role of the microbiome. -

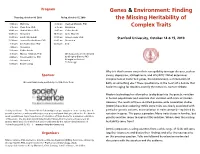

Genes & Environment: Finding the Missing Heritability of Complex Traits

Program Genes & Environment: Finding Thursday, October 14, 2010 Friday, October 15, 2010 the Missing Heritability of 9:00 am Welcome 8:30 am Stephen Manuck, PhD 9:15 am Steve Cole, PhD 9:15 am Discussion Complex Traits 10:00 am Ahmad Hariri, PhD 9:45 am Coffee break 10:45 am Discussion 10:15 am Anne Wojcicki 11:30 am Lunch (Provided) 11:00 am James Fowler, PhD Stanford University, October 14 & 15, 2010 12:30 pm Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, PhD 11:45 am Discussion 1:15 pm Eric Turkheimer, PhD 12:30 pm End 2:00 pm Discussion 2:45 pm Coffee break 3:15 pm Marcus Feldman, PhD All discussions are moderated 4:00 pm David Goldstein, PhD by Gregory Gibson, PhD 4:45 pm Discussion Georgia Institute of Technology 5:30 pm End First Day Why is it that humans vary in their susceptibility to major diseases, such as Sponsor cancer, depression, schizophrenia, and HIV/AIDS? What determines complex human traits? Is it genes, the environment, a combination of This event was made possible by contributions from both, or something else? These questions lie at the heart of a debate that has been raging for decades, namely the nature vs. nurture debate. Modern technology has allowed us to dig deep into the genetic variation in human populations and associate that variation with traits of interest. However, the results of these so-called genome wide association studies (GWAS) have been sobering: While some traits are clearly associated with Society in Science – The Branco Weiss Fellowship is unique anywhere in the world, since it particular genetic variants, most variation in traits cannot be explained by provides junior researchers with a generous personal grant that gives them the freedom to variation in genes.