Table S1. Nakharuthai and Srisapoome (2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disease and Clinical Signs Poster

African Clawed Frog Xenopus laevis Diseases and Clinical Signs in Photographs Therese Jones-Green University Biomedical Services Abstract Reported clinical signs associated with ill health and Clinical signs found between 2016 to 2018 Many diseases of Xenopus laevis frogs have been described in the • Opened in 2005, the biofacility can hold up to 900 female and 240 disease Clinical signs found between 2016 to 2018 male frogs in a Marine Biotech (now serviced by MBK Installations Ltd.) • 80 recirculating aquatic system. • Buoyancy problems 70 bridge this gap using photographs taken of frogs with clinical signs. The system monitors parameters such as: temperature, pH, • • Changes in activity e.g. lethargy or easily startled. My aims are: conductivity, and Total Gas Pressure. 60 • Unusual amount of skin shedding. 2018 • To share my experiences, via images, to help improve the welfare and • Frogs are maintained on mains fed water with a 20% water exchange. 50 ases • Weight loss, or failure to feed correctly. c husbandry of this species. • 2017 • Coelomic (body cavity) distention. 40 • To stimulate a dialogue which results in further sharing of ideas and 2016 Whole body bloat. 30 information. • Frogs are held under a 12 hour light/dark cycle. • Number of • Each tank has a PVC enrichment tube (30cm x 10cm), with smoothed • Fungal strands/tufts. 20 Introduction cut edges. • Sores or tremors at extremities (forearms and toes). 10 Between January 2016 and October 2018, cases of ill health and disease • Frogs are fed three times a week with a commercial trout pellet. • Redness or red spots. 0 Oedema Red leg Red leg (bad Red leg Gas bubble Sores on forearm Opaque cornea Skeletal Growth (cartilage Scar Cabletie Missing claws Eggbound in a colony of Xenopus laevis frogs housed by the University Biological hormone) (nematodes) disease deformity under skin) • The focus of the research undertaken in the biofacility is embryonic and • Excessive slime/mucous production or not enough (dry dull skin). -

Mouse Models of Human Disease an Evolutionary Perspective Robert L

170 commentary Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health [2016] pp. 170–176 doi:10.1093/emph/eow014 Mouse models of human disease An evolutionary perspective Robert L. Perlman* Department of Pediatrics, The University of Chicago, 5841 S. Maryland Ave, MC 5058, Chicago, IL 60637, USA *E-mail: [email protected] Received 31 December 2015; revised version accepted 12 April 2016 ABSTRACT The use of mice as model organisms to study human biology is predicated on the genetic and physio- logical similarities between the species. Nonetheless, mice and humans have evolved in and become adapted to different environments and so, despite their phylogenetic relatedness, they have become very different organisms. Mice often respond to experimental interventions in ways that differ strikingly from humans. Mice are invaluable for studying biological processes that have been conserved during the evolution of the rodent and primate lineages and for investigating the developmental mechanisms by which the conserved mammalian genome gives rise to a variety of different species. Mice are less reliable as models of human disease, however, because the networks linking genes to disease are likely to differ between the two species. The use of mice in biomedical research needs to take account of the evolved differences as well as the similarities between mice and humans. KEYWORDS: allometry; cancer; gene networks; life history; model organisms transgenic, knockout, and knockin mice, have If you have cancer and you are a mouse, we can provided added impetus and powerful tools for take good care of you. Judah Folkman [1] mouse research, and have led to a dramatic increase in the use of mice as model organisms. -

Micromys Minutus)

Acta Theriol (2013) 58:101–104 DOI 10.1007/s13364-012-0102-0 SHORT COMMUNICATION The origin of Swedish and Norwegian populations of the Eurasian harvest mouse (Micromys minutus) Lars Råberg & Jon Loman & Olof Hellgren & Jeroen van der Kooij & Kjell Isaksen & Roar Solheim Received: 7 May 2012 /Accepted: 17 September 2012 /Published online: 29 September 2012 # Mammal Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences, Białowieża, Poland 2012 Abstract The harvest mouse (Micromys minutus) occurs the Mediterranean, from France to Russia and northwards throughout most of continental Europe. There are also two to central Finland (Mitchell-Jones et al. 1999). Recently, isolated and recently discovered populations on the it has also been found to occur in Sweden and Norway. Scandinavian peninsula, in Sweden and Norway. Here, we In 1985, an isolated population was discovered in the investigate the origin of these populations through analyses province of Dalsland in western Sweden (Loman 1986), of mitochondrial DNA. We found that the two populations and during the last decade, this population has been on the Scandinavian peninsula have different mtDNA found to extend into the surrounding provinces as well haplotypes. A comparison of our haplotypes to published as into Norway. The known distribution in Norway is sequences from most of Europe showed that all Swedish and limited to a relatively small area close to the Swedish Norwegian haplotypes are most closely related to the border, in Eidskog, Hedmark (van der Kooij et al. 2001; haplotypes in harvest mice from Denmark. Hence, the two van der Kooij et al., unpublished data). In 2007, another populations seem to represent independent colonisations but population was discovered in the province of Skåne in originate from the same geographical area. -

A Guide to Mites

A GUIDE TO MITES concentrated in areas where clothes constrict the body, or MITES in areas like the armpits or under the breasts. These bites Mites are arachnids, belonging to the same group as can be extremely itchy and may cause emotional distress. ticks and spiders. Adult mites have eight legs and are Scratching the affected area may lead to secondary very small—sometimes microscopic—in size. They are bacterial infections. Rat and bird mites are very small, a very diverse group of arthropods that can be found in approximately the size of the period at the end of this just about any habitat. Mites are scavengers, predators, sentence. They are quite active and will enter the living or parasites of plants, insects and animals. Some mites areas of a home when their hosts (rats or birds) have left can transmit diseases, cause agricultural losses, affect or have died. Heavy infestations may cause some mites honeybee colonies, or cause dermatitis and allergies in to search for additional blood meals. Unfed females may humans. Although mites such as mold mites go unnoticed live ten days or more after rats have been eliminated. In and have no direct effect on humans, they can become a this area, tropical rat mites are normally associated with nuisance due to their large numbers. Other mites known the roof rat (Rattus rattus), but are also occasionally found to cause a red itchy rash (known as contact dermatitis) on the Norway rat, (R. norvegicus) and house mouse (Mus include a variety of grain and mold mites. Some species musculus). -

A Phylogeographic Survey of the Pygmy Mouse Mus Minutoides in South Africa: Taxonomic and Karyotypic Inference from Cytochrome B Sequences of Museum Specimens

A Phylogeographic Survey of the Pygmy Mouse Mus minutoides in South Africa: Taxonomic and Karyotypic Inference from Cytochrome b Sequences of Museum Specimens Pascale Chevret1*, Terence J. Robinson2, Julie Perez3, Fre´de´ric Veyrunes3, Janice Britton-Davidian3 1 Laboratoire de Biome´trie et Biologie Evolutive, UMR CNRS 5558, Universite´ Lyon 1, Villeurbanne, France, 2 Evolutionary Genomics Group, Department of Botany and Zoology, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 3 Institut des Sciences de l’Evolution de Montpellier, UMR CNRS 5554, Universite´ Montpellier 2, Montpellier, France Abstract The African pygmy mice (Mus, subgenus Nannomys) are a group of small-sized rodents that occur widely throughout sub- Saharan Africa. Chromosomal diversity within this group is extensive and numerous studies have shown the karyotype to be a useful taxonomic marker. This is pertinent to Mus minutoides populations in South Africa where two different cytotypes (2n = 34, 2n = 18) and a modification of the sex determination system (due to the presence of a Y chromosome in some females) have been recorded. This chromosomal diversity is mirrored by mitochondrial DNA sequences that unambiguously discriminate among the various pygmy mouse species and, importantly, the different M. minutoides cytotypes. However, the geographic delimitation and taxonomy of pygmy mice populations in South Africa is poorly understood. To address this, tissue samples of M. minutoides were taken and analysed from specimens housed in six South African museum collections. Partial cytochrome b sequences (400 pb) were successfully amplified from 44% of the 154 samples processed. Two species were identified: M. indutus and M. minutoides. The sequences of the M. indutus samples provided two unexpected features: i) nuclear copies of the cytochrome b gene were detected in many specimens, and ii) the range of this species was found to extend considerably further south than is presently understood. -

Rats and Mice Have Always Posed a Threat to Human Health

Rats and mice have always posed a threat to human health. Not only do they spread disease but they also cause serious damage to human food and animal feed as well as to buildings, insulation material and electricity cabling. Rats and mice - unwanted house guests! RATS AND MICE ARE AGILE MAMMALS. A mouse can get through a small, 6-7 mm hole (about the diameter of a normal-sized pen) and a rat can get through a 20 mm hole. They can also jump several decimetres at a time. They have no problem climbing up the inside of a vertical sewage pipe and can fall several metres without injuring themselves. Rats are also good swimmers and can be underwater for 5 minutes. IN SWEDEN THERE ARE BASICALLY four different types of rodent that affect us as humans and our housing: the brown rat, the house mouse and the small and large field mouse. THE BROWN RAT (RATTUS NORVEGICUS) THRIVES in all human environments, and especially in damp environments like cellars and sewers. The brown rat is between 20-30 cm in length not counting its tail, which is about 15-23 cm long. These rats normally have brown backs and grey underbellies, but there are also darker ones. They are primarily nocturnal, often keep together in large family groups and dig and gnaw out extensive tunnel systems. Inside these systems, they build large chambers where they store food and build their nests. A pair of rats can produce between 800 and 1000 offspring a year. Since their young are sexually mature and can have offspring of their own at just 2-4 months old, rats reproduce extraordinarily quickly. -

Helical Insertion of Peptidoglycan Produces Chiral Ordering of the Bacterial Cell Wall

Helical insertion of peptidoglycan produces PNAS PLUS chiral ordering of the bacterial cell wall Siyuan Wanga,b, Leon Furchtgottc,d, Kerwyn Casey Huangd,1, and Joshua W. Shaevitza,e,1 aLewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544; bDepartment of Molecular Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544; cBiophysics Program, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; dDepartment of Bioengineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305; and eDepartment of Physics, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08854 AUTHOR SUMMARY Cells from all kingdoms of wall growth to demonstrate life face the task of that patterning of cell-wall constructing a specific, synthesis by left-handed mechanically robust three- MreB polymers leads to a dimensional (3D) cell shape right-handed chiral from molecular-scale organization of the glycan components. For many strands. This organization bacteria, maintaining a rigid, produces a left-handed rod-like shape facilitates a twisting of the cell body diverse range of behaviors during elongational growth. including swimming motility, We then confirm the detection of chemical existence of right-handed gradients, and nutrient access Fig. P1. Helical insertion of material into the bacterial cell wall (green) glycan organization in E. coli during elongational growth, guided by the protein MreB (yellow), leads and waste evacuation in by osmotically shocking biofilms. The static shape of to an emergent chiral order in the cell-wall network and twisting of the cell that can be visualized using surface-bound beads (red). surface-labeled cells and a bacterial cell is usually directly measuring the defined by the cell wall, a difference in stiffness macromolecular polymer network composed of glycan strands between the longitudinal and transverse directions. -

High Abundance of Invasive African Clawed Frog Xenopus Laevis in Chile: Challenges for Their Control and Updated Invasive Distribution

Management of Biological Invasions (2019) Volume 10, Issue 2: 377–388 CORRECTED PROOF Research Article High abundance of invasive African clawed frog Xenopus laevis in Chile: challenges for their control and updated invasive distribution Marta Mora1, Daniel J. Pons2,3, Alexandra Peñafiel-Ricaurte2, Mario Alvarado-Rybak2, Saulo Lebuy2 and Claudio Soto-Azat2,* 1Vida Nativa NGO, Santiago, Chile 2Centro de Investigación para la Sustentabilidad & Programa de Doctorado en Medicina de la Conservación, Facultad de Ciencias de la Vida, Universidad Andres Bello, Republica 440, Santiago, Chile 3Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Departamento de Matemáticas, Universidad Andres Bello, Santiago, Republica 470, Santiago, Chile Author e-mails: [email protected] (CSA), [email protected] (MM), [email protected] (DJP), [email protected] (APR), [email protected] (MAR), [email protected] (SL) *Corresponding author Citation: Mora M, Pons DJ, Peñafiel- Ricaurte A, Alvarado-Rybak M, Lebuy S, Abstract Soto-Azat C (2019) High abundance of invasive African clawed frog Xenopus Invasive African clawed frog Xenopus laevis (Daudin, 1802) are considered a major laevis in Chile: challenges for their control threat to aquatic environments. Beginning in the early 1970s, invasive populations and updated invasive distribution. have now been established throughout much of central Chile. Between September Management of Biological Invasions 10(2): and December 2015, we studied a population of X. laevis from a small pond in 377–388, https://doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2019. 10.2.11 Viña del Mar, where we estimated the population size and evaluated the use of hand nets as a method of control. First, by means of a non-linear extrapolation Received: 26 October 2018 model using the data from a single capture session of 200 min, a population size of Accepted: 7 March 2019 1,182 post-metamorphic frogs (range: 1,168–1,195 [quadratic error]) and a density Published: 16 May 2019 of 13.7 frogs/m2 (range: 13.6–13.9) of surface water were estimated. -

Mice Are Here to Stay

Mice A re Here to Stay Wherever people live, there are mice. It would be difficult to find another animal that has adapted to the habitats created by humans as well as the house mouse has. It thus seemed obvious to Diethard Tautz at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Plön that the species would make an ideal model system for investigating how evolution works. BIOLOGY & MEDICINE_Evolution Mice A re Here to Stay TEXT CORNELIA STOLZE he mice at the Max Planck mice themselves only within a range of can be a key factor in the emergence of Institute in Plön live in their 30 to 50 centimeters, they convey high- new species. For Tautz, the house very own house: they have ly complex messages. mouse is a model for the processes of 16 rooms where they can Diethard Tautz and his colleagues evolution: it would be difficult to find form their family clans and have discovered that house mice be- another animal species that lends itself T territories as they see fit. The experi- have naturally only when they live in so well to the study of the genetic ments Tautz and his colleagues carry a familiar environment and interact mechanisms of evolution. out to study such facets as the rodents’ with other members of their species. “Not only is this species extremely communication, behavior and partner- When animals living in the wild are adaptable, as demonstrated by its dis- ships sometimes take months. During captured, they lose their familiar envi- persal all over the globe, but we also this time, the mice are largely left to ronment: everything smells and tastes know its genome better than that of al- their own devices. -

APPENDIX K: Accepted ECOTOX Data Table

APPENDIX K: Accepted ECOTOX Data Table The code list for ECOTOX can be found at: http://cfpub.epa.gov/ecotox/blackbox/help/codelist.pdf CAS Number Chemical Name Genus Species Common Name Effect Group Effect Meas Endpt1 Endpt2 Dur Preferred Conc Value1 Preferred Conc Value2 Preferred Conc Units Preferred % Purity Ref # 330541 Diuron Pimephales promelas Fathead minnow ACC ACC GACC BCF 1 TO 24 0.00315 TO 0.0304 mg/L 100 12612 330541 Diuron Rattus norvegicus Norway rat BCM BCM PHPH NOAEL 140 2500 ppm 100 90555 330541 Diuron Zostera capricorni Eelgrass BCM BCM FLRS LOAEL 8.33E-02 0.01 mg/L 100 72996 330541 Diuron Zostera capricorni Eelgrass BCM BCM FLRS LOAEL 8.33E-02 0.01 mg/L 100 72996 330541 Diuron Zostera capricorni Eelgrass BCM BCM FLRS LOAEL 8.33E-02 0.01 mg/L 100 72996 330541 Diuron Seriatopora hystrix Coral BCM BCM FLRS NOEC LOEC 0.416666667 0.0003 0.0003 mg/L 100 75334 330541 Diuron Seriatopora hystrix Coral BCM BCM FLRS EC25 0.416666667 0.00085 mg/L 100 75334 330541 Diuron Seriatopora hystrix Coral BCM BCM FLRS EC50 0.416666667 0.0023 mg/L 100 75334 330541 Diuron Acropora formosa Stony coral BCM BCM FLRS NOEC LOEC 1 0.00003 0.0003 mg/L 100 75334 330541 Diuron Acropora formosa Stony coral BCM BCM FLRS EC25 1 0.0012 mg/L 100 75334 330541 Diuron Acropora formosa Stony coral BCM BCM FLRS EC50 1 0.0027 mg/L 100 75334 330541 Diuron Synechococcus sp. Blue-green algae BCM BCM CHCT NOAEL 3 0.0033 mg/L 99 98904 330541 Diuron Lemna minor Duckweed BCM BCM GLTH LOAEL 2 0.02475 mg/L >99 64164 330541 Diuron Scenedesmus acutus Green Algae BCM BCM -

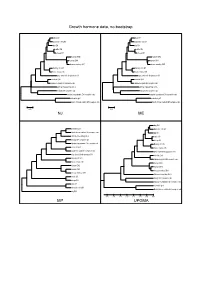

Growth Hormone Data, No Bootstrap NJ ME MP UPGMA

Growth hormone data, no bootstrap dog GH dog GH domestic cat GH domestic cat GH pig GH pig GH cattle GH cattle GH sheep GH sheep GH human GH2 human GH2 human GH1 human GH1 rhesus monkey GH1 rhesus monkey GH1 Norway rat Gh1 Norway rat Gh1 house mouse Gh house mouse Gh gray short-tailed opossum GH gray short-tailed opossum GH chicken GH1 chicken GH1 Japanese quail GH complete cds Japanese quail GH complete cds African clawed frog Gh A African clawed frog Gh A beluga GH complete cds beluga GH complete cds banded houndshark GH complete cds banded houndshark GH complete cds zebrafish gh1 zebrafish gh1 North African catfish GH complete cds North African catfish GH complete cds 0.05 0.05 NJ ME dog GH zebrafish gh1 domestic cat GH North African catfish GH complete cds pig GH African clawed frog Gh A cattle GH beluga GH complete cds sheep GH banded houndshark GH complete cds Norway rat Gh1 chicken GH1 house mouse Gh Japanese quail GH complete cds gray short-tailed opossum GH gray short-tailed opossum GH chicken GH1 Norway rat Gh1 Japanese quail GH complete cds house mouse Gh human GH2 human GH2 human GH1 human GH1 rhesus monkey GH1 rhesus monkey GH1 African clawed frog Gh A cattle GH beluga GH complete cds sheep GH banded houndshark GH complete cds dog GH zebrafish gh1 domestic cat GH North African catfish GH complete cds pig GH 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.20 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00 MP UPGMA Growth hormone data, 1000x bootstrapping 96 dog GH 95 dog GH 85 domestic cat GH 93 domestic cat GH 79 pig GH 81 pig GH cattle GH cattle GH 92 77 100 sheep GH 100 sheep GH -

Xenopus Laevis

Guidance on the housing and care of the African clawed frog Xenopus laevis Barney T Reed Research Animals Department - RSPCA Guidelines for the housing and care of the African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) May 2005 Guidance on the housing and care of the African clawed frog Xenopus laevis) Acknowledgements The author would like to sincerely thank the following people for their helpful and constructive comments during the preparation of this report: Mr. D. Anderson - Home Office, Animals Scientific Procedures Division Mr. M. Brown - MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge Dr. G. Griffin - Canadian Council for Animal Care (CCAC) Dr. M. Guille - School of Biological Sciences, University of Portsmouth Dr. P. Hawkins - Research Animals Department, RSPCA Dr. R. Hubrecht - Universities Federation for Animal Welfare (UFAW) Dr. M. Jennings - Research Animals Department, RSPCA Dr. K. Mathers - MRC National Institute for Medical Research Dr. G. Sanders - School of Medicine, University of Washington Prof. R. Tinsley - School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol Special thanks also to those organisations whose establishments I visited and whose scientific and animal care staff provided valuable input and advice. Note: The views expressed in this document are those of the author, and may not necessarily represent those of the persons named above or their affiliated organisations. About the author Barney Reed studied psychology and biology at the University of Exeter before obtaining a MSc in applied animal behaviour and animal welfare from the University of Edinburgh. He worked in the Animals Scientific Procedures Division of the Home Office before joining the research animals department of the RSPCA as a scientific officer.