Influences on Native Language Revitalization in the U.S.: Ideology and Culture Amelia Chantal Shettle Purdue University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John P. Harrington Papers 1907-1959

THE PAPERS OF John Peabody Harringtan IN THE Smithsonian Institution 1907-1957 VOLUME FIVE A GUIDE TO THE FIELD NOTES: NATIVE AMERICAN HISTORY, LANGUAGE, AND CULTURE OF THE PLAINS EDITED BY Elaine L. Mills and AnnJ Brickfield KRAUS INTERNATIONAL PUBLICATIONS A' Division of Kraus-Thomson Organization Limited THE PAPERS OF John Peabody Harringtan IN THE Smithsonian Institution 1907-1957 VOLUME FIVE A GUIDE TO THE FIELD NOTES: Native American History, Language, and Culture of the Plains I I Ie '''.'!:i~';i;:'':''} ~"'.:l' f' ...III Prepared in the National Anthropological Archives Department ofAnthropology National Museum ofNatural History Washington, D.C. THE PAPERS OF John Peabody Harringtan IN THE Smithsonian Institution 1907-1957 VOLUME FIVE A GUIDE TO THE FIELD NOTES: Native American History, Language, and Culture of the Plains EDITED BY Elaine L. Mills and Ann J. Brickfield KRAUS INTERNATIONAL PUBLICATIONS A Division of Kraus-Thomson Organization Limited White Plains, N.Y. © Copyright The Smithsonian Institution 1987 All rights reserved. No part ofthis work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced o~ used in any form or by any means-graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or taping, information storage and retrieval systems-without written permission ofthe publisher. First Printing Printed in the United States of America Contents The paper in this publication meets the minimum INTRODUCTION V I requirements of American National Standard for Scope and Content of this PUblic~t~on V / V1/t Information Science- Permanence of Papers for V / vtn Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. History of the Papers and the Microfilm Edttwn Editorial Procedures V / x Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Acknowledgements V / xii Harrington, John Peabody. -

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas edited by Andrea L. Berez, Jean Mulder, and Daisy Rosenblum Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 2 Published as a sPecial Publication of language documentation & conservation language documentation & conservation Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822 USA http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc university of hawai‘i Press 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822-1888 USA © All texts and images are copyright to the respective authors. 2010 All chapters are licensed under Creative Commons Licenses Cover design by Cameron Chrichton Cover photograph of salmon drying racks near Lime Village, Alaska, by Andrea L. Berez Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data ISBN 978-0-8248-3530-9 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4463 Contents Foreword iii Marianne Mithun Contributors v Acknowledgments viii 1. Introduction: The Boasian tradition and contemporary practice 1 in linguistic fieldwork in the Americas Daisy Rosenblum and Andrea L. Berez 2. Sociopragmatic influences on the development and use of the 9 discourse marker vet in Ixil Maya Jule Gómez de García, Melissa Axelrod, and María Luz García 3. Classifying clitics in Sm’algyax: 33 Approaching theory from the field Jean Mulder and Holly Sellers 4. Noun class and number in Kiowa-Tanoan: Comparative-historical 57 research and respecting speakers’ rights in fieldwork Logan Sutton 5. The story of *o in the Cariban family 91 Spike Gildea, B.J. Hoff, and Sérgio Meira 6. Multiple functions, multiple techniques: 125 The role of methodology in a study of Zapotec determiners Donna Fenton 7. -

Mother Tongue Film Festival

2016–2020 Mother Tongue Film Festival Five-Year Report RECOVERING VOICES 1 2 3 Introduction 5 By the Numbers 7 2016 Festival 15 2017 Festival 25 2018 Festival 35 2019 Festival 53 2020 Festival 67 Looking Ahead 69 Appendices Table of Contents View of the audience at the Last Whispers screening, Terrace Theater, Kennedy Center. Photo courtesy of Lena Herzog 3 4 The Mother Tongue Film Festival is a core to the Festival’s success; over chance to meet with guest artists and collaborative venture at the Smithso- time, our partnerships have grown, directors in informal sessions. We nian and a public program of Recov- involving more Smithsonian units and have opened the festival with drum ering Voices, a pan-institutional pro- various consular and academic part- and song and presented live cultural gram that partners with communities ners. When launched, it was the only performances as part of our festival around the world to revitalize and festival of its kind, and it has since events. sustain endangered languages and formed part of a small group of local knowledge. The Recovering Voices and international festivals dedicated We developed a dedicated, bilingual partners are the National Museum of to films in Indigenous languages. (English and Spanish) website for Natural History, the National Museum the festival in 2019, where we stream of the American Indian, and the Cen- Over its five editions, the festival has several works in full after the festival. ter for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. grown, embracing a wide range of And, given the changing reality of our Through interdisciplinary research, audiovisual genres and experiences, world, we are exploring how to pres- community collaboration, and pub- drawing audiences to enjoy screen- ent the festival in a hybrid live/on- lic outreach, we strive to develop ef- ings often at capacity at various ven- line model, or completely virtually, in fective responses to language and ues around Washington, DC. -

Spring 2018 Newsletter

Message from the Chair Linguistics is a thriving field. We have On a positive note, we have a lot of positioned ourselves as a unique pro- good news to report. Alison Gabriele gram that integrates linguistic theory was promoted to Full Professor. Alison with experimental research. This was joined the department in 2005, became showcased at our 50th Anniversary cel- an Associate Professor with tenure in ebration in September 2017. We were 2011, and will be a Full Professor as of thrilled that many of you were able to August 2018. Congratulations Alison! come back to partake in the festivities Andrew McKenzie was promoted to to celebrate this milestone. The cele- Associate Professor with tenure. An- bration had talks by former and current drew joined the department in 2012, students, by faculty, a lively poster ses- and will be an Associate Professor with sion, lab tours, and a lot of entertaining tenure as of August 2018. Congratu- Inside this issue: Linguistic conversations. Both our first lations Andrew! The department also Ph.D. and our most recent Ph.D. were hired John Gluckman, who is finishing Frances Ingemann present. The Anniversary was also a his Ph.D. at UCLA and will be joining Tribute 2 chance for alumni, students, and fac- the department in the Fall. John’s re- 50th Anniversary 4 ulty to give back to the Department. search specialty is in the area of syntax, Faculty News 5 We encouraged donations with the cre- semantics, and morphology, with inter- Frances Ingemann ation of very Linguistic levels of giv- ests in fieldwork on understudied lan- Scholarship 8 ing: Verb, Deixis, Wug, Uvula, ERP, guage varieties in Africa, Asia, and the Frances Ingemann and Critical Period and we received Americas. -

West Greenlandic Eskimo & Haida 1. Introduction in This Chapter, We

Chapter 4 The Constitution of FOCUS: West Greenlandic Eskimo & Haida 1. Introduction In this chapter, we introduce West Greenlandic Eskimo and Haida and outline portions of two languages which are associated with the expression of FOCUS. One language will exploit sentence initial position and one, sentence final position. They will also differ in how/whether they wed other semantics with FOCUS, and they will differ in how they associate other semantics with FOCUS. These interplays afford us the opportunity to enrich our conceptuali- zation of FOCUS. 2. West Greenlandic Eskimo West Greenlandic Eskimo (WGE) is a language that places S, O, and V in that order in the most neutral expressions:1 SOXV is clearly the neutral order (Sadock 1984.196) 1 The following is from the webpage of the Alaska Native Language Center (http://www.uaf.edu/anlc/): Although the name “Eskimo” is commonly used in Alaska to refer to all Inuit and Yupik people of the world, this name is considered derogatory in many other places because it was given by non-Inuit people and was said to mean “eater of raw meat.” Linguists now believe that “Eskimo” is derived from an Ojibwa word meaning “to net snowshoes.” However, the people of Canada and Greenland prefer other names. “Inuit,” meaning “people,” is used in most of Canada, and the language is called “Inuktitut” in eastern Canada although other local designations are used also. The Inuit people of Greenland refer to themselves as “Greenlanders” or “Kalaallit” in their language, which they call “Greenlandic” or “Kalaallisut.” Most Alaskans continue to accept the name “Eskimo,” particularly because “Inuit” refers only to the Inupiat of northern Alaska, the Inuit of Canada, and the Kalaallit of Greenland, and is not a word in the Yupik languages of Alaska and Siberia. -

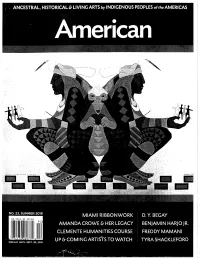

The Clemente Course in the Humanities;' National Endowment for the Humanities, 2014, Web

F1rstAmericanArt ISSUE NO. 23, SUMMER 2019 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Take a Closer Look: 24 Recent Developments 16 Four Emerging Artists By Mariah L. Ashbacher Shine in the Spotlight and America Meredith By RoseMary Diaz ( Cherokee Nation) (Santa Clara Tewa) Seven Directions 20 Amanda Crowe & Her Legacy: 30 By Hallie Winter (Osage Nation) Eastern Band Cherokee Art+ Literature 96 Woodcarving Suzan Shown Harjo By Tammi). Hanawalt, PhD By Matthew Ryan Smith, PhD peepankisaapiikahkia 36 Collections: 100 eehkwaatamenki aacimooni: The Metropolitan Museum of Art A Story of Miami Ribbonwork By Andrea L. Ferber, PhD By Scott M. Shoemaker, PhD Spotlight: Melt: Prayers 104 (Miami), George Ironstrack for the People and the Planet, (Miami), and Karen Baldwin Angela Babby (Oglala Lakota) By Mariah L. Ashbacher Reclaiming Space in Native 44 Calendar 109 Knowledges and Languages By Travis D. Day and America The Clemente Course Meredith (Cherokee Nation) in the Humanities By Laura Marshall Clark (Muscogee Creek) REVIEWS Exhibition Reviews 78 ARTIST PROFILES Book Review 94 D. Y.Begay: 54 Dine Textile Artist By Jennifer McLerran, PhD IN MEMORIAM Benjamin Harjo Jr.: 60 Joe Fafard, OC, SOM (Melis) 106 Absentee Shawnee/Seminole Painter By Gloria Bell, PhD (Metis) and Printmaker Frank LaPefta 107 By Staci Golar (Nomtipom Maidu) By Mariah L. Ashbacher Freddy Mamani Silvestre: 66 Truman Lowe (Ho-Chunk) Aymara Architect By jean Merz-Edwards By Vivian Zavataro, PhD Tyra Shackleford: 72 Chickasaw Textile Artist By Vicki Monks (Chickasaw) COVER Benjamin Harjo 'Jr. (Absentee Shawnee/ Seminole), creator and coyote compete to make man, 2016, gouache on Arches watercolor paper, 20 x 28 in., private collection. -

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory: Table of Contents and Section Descriptions 1. Linguistic Resources Academic linguistics articles, reference materials, and online language resources for each BC First Nations language. 2. Language-Specific Resources Practical teaching resources and curriculum identified for each BC First Nations language. 3. Adaptable Resources General curriculum and teaching resources which can be adapted for teaching BC First Nations languages: books, curriculum documents, online and multimedia resources. Includes copies of many documents in PDF format. 4. Language Revitalization Resources This section includes general resources on language revitalization, as well as resources on awakening languages, teaching methods for language revitalization, materials and activities for language teaching, assessing the state of a language, envisioning and planning a language program, teacher training, curriculum design, language acquisition, and the role of technology in language revitalization. 5. Language Teaching Journals A list of journals relevant to teachers of BC First Nations languages. 6. Further Education This section highlights opportunities for further education, training, certification, and professional development. It includes a list of conferences and workshops relevant to BC First Nations language teachers, and a spreadsheet of post‐ secondary programs relevant to Aboriginal Education and Teacher Training - in BC, across Canada, in the USA, and around the world. 7. Funding This section includes a list of funding sources for Indigenous language revitalization programs, as well as a list of scholarships and bursaries available for Aboriginal students and students in the field of Education, in BC, across Canada, and at specific institutions. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Russian American Contacts, 1917-1937: a Review Article

names of individual forts; names of M. Odivetz, and Paul J. Novgorotsev, Rydell, Robert W., All the World’s a Fair: individual ships 20(3):235-36 Visions of Empire at American “Russian American Contacts, 1917-1937: Russian Shadows on the British Northwest International Expositions, 1876-1916, A Review Article,” by Charles E. Coast of North America, 1810-1890: review, 77(2):74; In the People’s Interest: Timberlake, 61(4):217-21 A Study of Rejection of Defence A Centennial History of Montana State A Russian American Photographer in Tlingit Responsibilities, by Glynn Barratt, University, review, 85(2):70 Country: Vincent Soboleff in Alaska, by review, 75(4):186 Ryesky, Diana, “Blanche Payne, Scholar Sergei Kan, review, 105(1):43-44 “Russian Shipbuilding in the American and Teacher: Her Career in Costume Russian Expansion on the Pacific, 1641-1850, Colonies,” by Clarence L. Andrews, History,” 77(1):21-31 by F. A. Golder, review, 6(2):119-20 25(1):3-10 Ryker, Lois Valliant, With History Around Me: “A Russian Expedition to Japan in 1852,” by The Russian Withdrawal From California, by Spokane Nostalgia, review, 72(4):185 Paul E. Eckel, 34(2):159-67 Clarence John Du Four, 25(1):73 Rylatt, R. M., Surveying the Canadian Pacific: “Russian Exploration in Interior Alaska: An Russian-American convention (1824), Memoir of a Railroad Pioneer, review, Extract from the Journal of Andrei 11(2):83-88, 13(2):93-100 84(2):69 Glazunov,” by James W. VanStone, Russian-American Telegraph, Western Union Ryman, James H. T., rev. of Indian and 50(2):37-47 Extension, 72(3):137-40 White in the Northwest: A History of Russian Extension Telegraph. -

Keeping Haida Alive Through Film and Drama

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 20 Collaborative Approaches to the Challenge of Language Documentation and Conservation: Selected papers from the 2018 Symposium on American Indian Languages (SAIL) ed. by Wilson de Lima Silva and Katherine Riestenberg, p.107-122 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ 8 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24935 Keeping Haida alive through film and drama Frederick White Slippery Rock University The Haida language, of the northwest coast of Canada and Southern Alaska, has been endangered for most of the 20th century. Historically, orthography has been a difficult issue for anyone studying the language, since no standardized orthography existed. In spite of the orthographical issues, current efforts in Canada at revitalizing Haida lan- guage and culture have culminated in the theatrical production of Sinxii’gangu, a tradi- tional Haida story dramatized and performed completely in Haida. The most recent effort is Edge of the Knife, a film about a Haida man transforming into a gaagiid (wild man) as a result of losing a child. The story line addresses his restoration back into the community, and as a result, affords not just a resource for two Haida dialects, but also for history and culture. With regards to language, actors participated in two weeks of immersion to prepare and struggled through issues with Haida pronunciation during filming. Using the Haida language exclusively, not just in oral narratives (though there are some in the drama and the film) but in actual dialogue, provides learners with great context for developing strategies for pronunciation and conversation rather than only learning and hearing lexical items and short phrases. -

On the External Relations of Purepecha: an Investigation Into Classification, Contact and Patterns of Word Formation Kate Bellamy

On the external relations of Purepecha: An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation Kate Bellamy To cite this version: Kate Bellamy. On the external relations of Purepecha: An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation. Linguistics. Leiden University, 2018. English. tel-03280941 HAL Id: tel-03280941 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03280941 Submitted on 7 Jul 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/61624 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Bellamy, K.R. Title: On the external relations of Purepecha : an investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation Issue Date: 2018-04-26 On the external relations of Purepecha An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation Published by LOT Telephone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht Email: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration: Kate Bellamy. ISBN: 978-94-6093-282-3 NUR 616 Copyright © 2018: Kate Bellamy. All rights reserved. On the external relations of Purepecha An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation PROEFSCHRIFT te verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College Speaking Kiowa Today

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE SPEAKING KIOWA TODAY: CONTINUITY AND CHANGE THROUGH THE GENERATIONS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By AMBER A. NEELY Norman, Oklahoma 2015 SPEAKING KIOWA TODAY: CONTINUITY AND CHANGE THROUGH THE GENERATIONS A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Gus Palmer Jr., Co-Chair ______________________________ Dr. Sean P. O’Neill, Co-Chair ______________________________ Dr. Daniel Swan ______________________________ Dr. Lesley Rankin-Hill ______________________________ Dr. Marcia Haag © Copyright by AMBER A. NEELY 2015 All Rights Reserved. To my dearest Kiowa friends, who have welcomed me into their folds and believed in me all these years: Prof. Gus Palmer, Jr., Grandma Dorothy Whitehorse DeLaune, Mrs. Delores Harragarra and the Harragarra family, as well as all those who are dedicated to the revitalization of the Kiowa language. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so grateful to so many people for sharing their lives, their knowledge, their friendship, and of course, their language. Since this work is about the speakers of Kiowa, I would like to start there. Let me first thank those who have meant so much to me through the years, welcoming me almost as family. First and foremost, I wish to honor Mrs. Delores Toyebo Harragarra and Grandma Dorothy Whitehorse DeLaune, both of whose grace, humor, and insight inspire me daily, and who have both played a great role in the unfolding of this project. The enigmatic Kenny Harragarra, whose company is always a delight, and the rest of the Harragarra family, as well as Mrs.