Keeping Haida Alive Through Film and Drama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mother Tongue Film Festival

2016–2020 Mother Tongue Film Festival Five-Year Report RECOVERING VOICES 1 2 3 Introduction 5 By the Numbers 7 2016 Festival 15 2017 Festival 25 2018 Festival 35 2019 Festival 53 2020 Festival 67 Looking Ahead 69 Appendices Table of Contents View of the audience at the Last Whispers screening, Terrace Theater, Kennedy Center. Photo courtesy of Lena Herzog 3 4 The Mother Tongue Film Festival is a core to the Festival’s success; over chance to meet with guest artists and collaborative venture at the Smithso- time, our partnerships have grown, directors in informal sessions. We nian and a public program of Recov- involving more Smithsonian units and have opened the festival with drum ering Voices, a pan-institutional pro- various consular and academic part- and song and presented live cultural gram that partners with communities ners. When launched, it was the only performances as part of our festival around the world to revitalize and festival of its kind, and it has since events. sustain endangered languages and formed part of a small group of local knowledge. The Recovering Voices and international festivals dedicated We developed a dedicated, bilingual partners are the National Museum of to films in Indigenous languages. (English and Spanish) website for Natural History, the National Museum the festival in 2019, where we stream of the American Indian, and the Cen- Over its five editions, the festival has several works in full after the festival. ter for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. grown, embracing a wide range of And, given the changing reality of our Through interdisciplinary research, audiovisual genres and experiences, world, we are exploring how to pres- community collaboration, and pub- drawing audiences to enjoy screen- ent the festival in a hybrid live/on- lic outreach, we strive to develop ef- ings often at capacity at various ven- line model, or completely virtually, in fective responses to language and ues around Washington, DC. -

TIFF Premiere: Sgaawaay K'uuna, the First Feature Film About the Haida People

Academic rigour, journalistic flair TIFF premiere: Sgaawaay K'uuna, the first feature film about the Haida people September 5, 2018 7.27pm EDT High school honour roll student Trey Arnold Rorick acts in the ‘Edge of the Knife.’ Rorick also works as a Cultural Interpreter at the K_ay Ilnagaay Haida Heritage Center. Facebook TIFF premiere: Sgaawaay K'uuna, the first feature film about the Haida people September 5, 2018 7.27pm EDT Sgaawaay K'uuna (Edge of the Knife), premiering at the Toronto International Film Author Festival, is the first feature film about the Haida people and in the Haida language. The mystery-thriller, directed by Gwaai Edenshaw and Helen Haig-Brown, started as a collaboration between myself at the University of British Columbia (UBC), the Inuit film production company Kingulliit and the Council of the Haida Nation (CHN). Leonie Sandercock Professor, University of British Columbia We hope the film will be a catalyst for language revitalization as well as community economic development. In 2012, fewer than one per cent of the Haida were fluent in the Haida language and most of those were over the age of 70, so the language was regarded as in crisis. Edge of the Knife emerged out the results of a community planning process our students had been involved in at Skidegate a year earlier, a year of community engagement and envisioning Haida hopes and dreams. The top three priorities identified by the Skidegate community were language revitalization, the creation of jobs that would keep youth on Haida Gwaii instead of moving to Vancouver and protecting the lands and waters of Haida Gwaii through sustainable economic development. -

West Greenlandic Eskimo & Haida 1. Introduction in This Chapter, We

Chapter 4 The Constitution of FOCUS: West Greenlandic Eskimo & Haida 1. Introduction In this chapter, we introduce West Greenlandic Eskimo and Haida and outline portions of two languages which are associated with the expression of FOCUS. One language will exploit sentence initial position and one, sentence final position. They will also differ in how/whether they wed other semantics with FOCUS, and they will differ in how they associate other semantics with FOCUS. These interplays afford us the opportunity to enrich our conceptuali- zation of FOCUS. 2. West Greenlandic Eskimo West Greenlandic Eskimo (WGE) is a language that places S, O, and V in that order in the most neutral expressions:1 SOXV is clearly the neutral order (Sadock 1984.196) 1 The following is from the webpage of the Alaska Native Language Center (http://www.uaf.edu/anlc/): Although the name “Eskimo” is commonly used in Alaska to refer to all Inuit and Yupik people of the world, this name is considered derogatory in many other places because it was given by non-Inuit people and was said to mean “eater of raw meat.” Linguists now believe that “Eskimo” is derived from an Ojibwa word meaning “to net snowshoes.” However, the people of Canada and Greenland prefer other names. “Inuit,” meaning “people,” is used in most of Canada, and the language is called “Inuktitut” in eastern Canada although other local designations are used also. The Inuit people of Greenland refer to themselves as “Greenlanders” or “Kalaallit” in their language, which they call “Greenlandic” or “Kalaallisut.” Most Alaskans continue to accept the name “Eskimo,” particularly because “Inuit” refers only to the Inupiat of northern Alaska, the Inuit of Canada, and the Kalaallit of Greenland, and is not a word in the Yupik languages of Alaska and Siberia. -

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory: Table of Contents and Section Descriptions 1. Linguistic Resources Academic linguistics articles, reference materials, and online language resources for each BC First Nations language. 2. Language-Specific Resources Practical teaching resources and curriculum identified for each BC First Nations language. 3. Adaptable Resources General curriculum and teaching resources which can be adapted for teaching BC First Nations languages: books, curriculum documents, online and multimedia resources. Includes copies of many documents in PDF format. 4. Language Revitalization Resources This section includes general resources on language revitalization, as well as resources on awakening languages, teaching methods for language revitalization, materials and activities for language teaching, assessing the state of a language, envisioning and planning a language program, teacher training, curriculum design, language acquisition, and the role of technology in language revitalization. 5. Language Teaching Journals A list of journals relevant to teachers of BC First Nations languages. 6. Further Education This section highlights opportunities for further education, training, certification, and professional development. It includes a list of conferences and workshops relevant to BC First Nations language teachers, and a spreadsheet of post‐ secondary programs relevant to Aboriginal Education and Teacher Training - in BC, across Canada, in the USA, and around the world. 7. Funding This section includes a list of funding sources for Indigenous language revitalization programs, as well as a list of scholarships and bursaries available for Aboriginal students and students in the field of Education, in BC, across Canada, and at specific institutions. -

Cabin Fever: Free Films for Kids! The

January / February 2019 Canadian & International Features NEW WORLD DOCUMENTARIES special Events THE GREAT BUSTER CABIN FEVER: FREE FILMS FOR KIDS! www.winnipegcinematheque.com January 2019 TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 1 2 3 4 5 6 closed: New Year’s Day Roma / 7 pm Roma / 7 pm & 9:30 pm Roma / 7 pm & 9:30 pm Roma / 3 pm & 7 pm cabin fever: Coco 3D / 3 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Canada’s Top Ten: Anthropocene: Anthropocene: The Human Epoch / 9:30 pm The Human Epoch / 5 pm Roma / 7 pm 8 9 10 11 12 13 The Last Movie / 7 pm Roma / 7 pm Jean-Pierre Melville: Black Lodge: Secret Cinema Roma / 2:30 pm cabin fever: The Big Bad Dial Code Santa Claus / 9 pm Le samouraï / 7 pm with the Laundry Room / 7 pm Jean-Pierre Melville: Fox and Other Tales… / 3 pm Roma / 9 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Léon Morin, Priest / 5 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Anthropocene: Canada’s Top Ten: Anthropocene: The Human Epoch / 7 pm Anthropocene: The Human Epoch / 5 pm Roma / 9 pm The Human Epoch / 7:15 pm Genesis / 7 pm Genesis / 9 pm 15 16 17 18 19 20 The Last Movie / 7 pm Jean-Pierre Melville: Canada’s Top Ten: Jean-Pierre Melville: The Great Buster / 3 pm & 7 pm cabin fever: Buster Keaton’s Dial Code Santa Claus / 9 pm Léon Morin, Priest / 7 pm Anthropocene: Le doulos / 7 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Classic Shorts / 3 pm The Human Epoch / 7 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Anthropocene: The Great Buster / 5 pm Roads in February / 9 pm Anthropocene: The Human Epoch / 5 pm Jean-Pierre Melville: The Human Epoch / 9 pm Roads in February / 9 pm Le samouraï / 7 pm 22 23 24 25 26 27 The Last -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

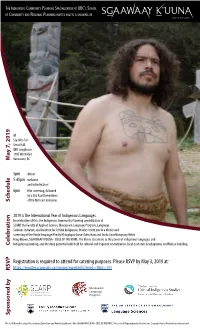

M Ay 7, 2019 C Elebration Sp Onsored B Y Registration Is Required To

THE INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY PLANNING SPECIALIZATION AT UBC’S SCHOOL OF COMMUNITY AND REGIONAL PLANNING INVITES YOU TO A SHOWING OF EDGE OF THE KNIFE at Sty-Wet-Tan Great Hall, UBC Longhouse 1985 West Mall May 7, 2019 May Vancouver, BC A FILM BY GWAAI EDENSHAW & HELEN HAIGBROWN 5pm dinner COUNCIL OF THE HAIDA NATION NIIJANG XYAALAS PRODUCTIONS PRODUCTION STARRING TYLER YORK WILLIAM RUSS ADEANA YOUNG AND TREY RORICK DELORES CHURCHILL XIILA GUUJAAW GWAAGANAD DIANE BROWN KINNIE STARR ATHENA THENY SARAH HEDAR SANDY COCHRANE JONATHAN FRANTZ ZACHARIAS KUNUK STEPHEN GROSSE JONATHAN FRANTZ 5:45pm welcome GWAAI EDENSHAW JAALEN EDENSHAW GRAHAM RICHARD LEONIE SANDERCOCK and introductions GWAAI EDENSHAW HELEN HAIGBROWN 6pm film screening, followed by a Q & A with members Schedule of the film cast and crew 2019 is The International Year of Indigenous Languages. In celebration of this, the Indigenous Community Planning specialization at SCARP, the Faculty of Applied Science, Musqueam Language Program, Language Sciences Initiative, and Institute for Critical Indigenous Studies invite you to a dinner and screening of the Haida language film by Hluugitgaa Gwaai Edenshaw and Jaada Gyaahlangnaay Helen Haig-Brown, SGAAWAAY K’UUNA - EDGE OF THE KNIFE. The film is testament to the power of Indigenous languages and Celebration Indigenous planning, and the deep potential both hold for cultural and linguistic revitalization, local economic development, and Nation-building. Registration is required to attend for catering purposes. Please RSVP by May 3, 2019 at: https://register.scarp.ubc.ca/civicrm/event/info?reset=1&id=131 RSVP Musqueam Language Program Sponsored by Sponsored Photo: William Russ plays Kwa in Gwaai Edenshaw and Helen Haig-Brown’s film SGAAWAAY K’UUNA -EDGE OF THE KNIFE. -

Reference Guide This List Is for Your Reference Only

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA ACT OF THE HEART BLACKBIRD 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / 2012 / Director-Writer: Jason Buxton / 103 min / English / PG English / 14A A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a Sean (Connor Jessup), a socially isolated and bullied teenage charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest conductor goth, is falsely accused of plotting a school shooting and in her church choir. Starring Geneviève Bujold and Donald struggles against a justice system that is stacked against him. Sutherland. BLACK COP ADORATION ADORATION 2017 / Director-Writer: Cory Bowles / 91 min / English / 14A 2008 / Director-Writer: Atom Egoyan / 100 min / English / 14A A black police officer is pushed to the edge, taking his For his French assignment, a high school student weaves frustrations out on the privileged community he’s sworn to his family history into a news story involving terrorism and protect. The film won 10 awards at film festivals around the invites an Internet audience in on the resulting controversy. world, and the John Dunning Discovery Award at the CSAs. With Scott Speedman, Arsinée Khanjian and Rachel Blanchard. CAST NO SHADOW 2014 / Director: Christian Sparkes / Writer: Joel Thomas ANGELIQUE’S ISLE Hynes / 85 min / English / PG 2018 / Directors: Michelle Derosier (Anishinaabe), Marie- In rural Newfoundland, 13-year-old Jude Traynor (Percy BEEBA BOYS Hélène Cousineau / Writer: James R. -

Edge of the Knife

EDGE OF THE KNIFE DIRECTED BY HELEN HAIG BROWN AND GWAAI EDENSHAW BASED ON AN ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY BY GWAAI EDENSHAW, JAALEN EDENSHAW, GRAHAM RICHARD AND LEONIE SANDERCOCK Edge of the Knife is a feature length Haida language film about pride, tragedy, and penance. The film draws its name from a Haida saying, "the world is as sharp as a knife" ‐ that as we walk along we have to be careful not to fall off one side or the other. This is the world we live in ‐ so close to nature, our lives always hanging in balance ‐ one slip can change everything. For Adiits’ii, the lead character in the film, that edge becomes razor thin as he is mentally and physically pushed to the brink of survival and becomes Gaagiixiid/Gaagiid ‐ the Haida Wildman. The Gaagiixiid is one of Haida’s most popular stories, sustained over the years though song and performance. The Gaagiixid describes a state of being that comes onto a person after they survive an accident at sea. Stranded and struggling for survival, their humanity gives way to a more bestial state. This project is a community initiative with strong support from the Haida people as well as from the Council of the Haida Nation. Script Synopsis Edge of the Knife is a story of survival and redemption, secrets and self‐discovery, set against the backdrop of the tangled rainforest and storm ravaged west coast of Haida Gwaii. Inspired by one of the Haida people’s most popular vital stories – the Gaagiixiid/Gaagiid (or Wildman) – this is a transformation tale with an uncertain ending. -

Linguistic Theory, Collaborative Language Documentation, and the Production of Pedagogical Materials

Introduction: Collaborative approaches to the challenges of language documentation and conservation edited by Wilson de Lima Silva Katherine J. Riestenberg Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 20 PUBLISHED AS A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai'i 96822 USA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu Hawai'i 96822 1888 USA © All texts and images are copyright to the respective authors, 2020 All chapters are licensed under Creative Commons Licenses Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International Cover designed by Katherine J. Riestenberg Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data ISBN-13: 978-0-9973295-8-2 http://hdl.handle.net/24939 ii Contents Contributors iv 1. Introduction: Collaborative approaches to the challenges of language 1 documentation and conservation Wilson de Lima Silva and Katherine J. Riestenberg 2. Integrating collaboration into the classroom: Connecting community 6 service learning to language documentation training Kathryn Carreau, Melissa Dane, Kat Klassen, Joanne Mitchell, and Christopher Cox 3. Indigenous universities and language reclamation: Lessons in balancing 20 Linguistics, L2 teaching, and language frameworks from Blue Quills University Josh Holden 4. “Data is Nice:” Theoretical and pedagogical implications of an Eastern 38 Cherokee corpus Benjamin Frey 5. The Kawaiwete pedagogical grammar: Linguistic theory, collaborative 54 language documentation, and the production of pedagogical materials Suzi Lima 6. Supporting rich and meaningful interaction in language teaching for 73 revitalization: Lessons from Macuiltianguis Zapotec Katherine J. Riestenberg 7. The Online Terminology Forum for East Cree and Innu: A collaborative 89 approach to multi-format terminology development Laurel Anne Hasler, Marie Odile Junker, Marguerite MacKenzie, Mimie Neacappo, and Delasie Torkornoo 8. -

Influences on Native Language Revitalization in the U.S.: Ideology and Culture Amelia Chantal Shettle Purdue University

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Theses Theses and Dissertations January 2015 Influences on Native Language Revitalization in the U.S.: Ideology and Culture Amelia Chantal Shettle Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_theses Recommended Citation Shettle, Amelia Chantal, "Influences on Native Language Revitalization in the U.S.: Ideology and Culture" (2015). Open Access Theses. 1203. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_theses/1203 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. INFLUENCES ON NATIVE AMERICAN LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION IN THE U.S.: IDEOLOGY AND CULTURE A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Amelia Chantal Shettle In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts December 2015 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my committee members, especially Daryl Baldwin for being added to the committee late and under no obligation to do so. Your addition to the committee has been invaluable, thank you. Also, Elena Benedicto, Myrdene Anderson, and Mary Niepokuj, your contributions, feedback, advice, and guidance have made this thesis what it is. I could not have completed it without the attention you have given to both it and me. In addition to direct feedback and advice, the ideas we have discussed in the classes and field trips I have taken with you have directly influenced different aspects of my research and I appreciate the discussions you each facilitated in those contexts. -

Edge of the Knife

EDGE OF THE KNIFE (dir. Gwaai Edenshaw & Helen Haig-Brown, 2018 – 100 mins) Gwaai Edenshaw's four-years-in-the-making labour-of-love SGaawaay K'uuna (Edge of the Knife) has drummed up international headlines for being made in a language only spoken fluently by 20 people. Haida is the language of the Haida Gwaii, an Indigenous first nations community based in an archipelago off the west coast of Canada. Edenshaw, who is Haida and speaks the language but not fluently, enlisted language mentors to ensure that his cast and the English subtitles were accurate. Set in the 19th century, the film is shot through with a tactile integrity as a result of using real Haida people's talents to create costumes, props and the sound design. A carver by trade, Edenshaw made several props himself, staying up all night to make a mask, a cane, a headdress and a dagger in order to use them on the next day's shoot. “Rather than being tired for the loss of sleep I actually would feel more invigorated in those times,” he says to me over the phone, “I had been missing carving so much it helped my own mental health to be able to get some done.” This holistic approach to the nature of creativity is found elsewhere with the production enabled by a combination of the conventional – funding secured with help from Inuit production company Isuma - and the traditional practice of pot-latching aka trading and gifting. The story is a magical realist period re-imagining (in the vein of Ciro Guerra's Embrace of the Serpent) powered by Shakespearean themes of tragedy, revenge and family.