Langscape-Magazine-Summer-And-Winter-2019-WEB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal Side, We Must Mention Prof

The Journal of Newar Studies Swayambhv, Ifliihichaitya Number - 2 NS 1119 (TheJournal Of Newar Studies) NUmkL2 U19fi99&99 It has ken a great pleasure bringing out the second issue of EdltLlo the journal d Newar Studies lijiiiina'. We would like to thank Daya R Sha a Gauriehankar Marw&~r Ph.D all the members an bers for their encouraging comments and financial support. ivc csp~iilly:-l*-. urank Prof. Uma Shrestha, Western Prof.- Todd ttwria Oregon Univers~ty,who gave life to this journd while it was still in its embryonic stage. From the Nepal side, we must mention Prof. Tej Shta Sudip Sbakya Ratna Kanskar, Mr. Ram Shakya and Mr. Labha Ram Tuladhar who helped us in so many ways. Due to our wish to publish the first issue of the journal on the Sd Fl~ternatioaalNepal Rh&a levi occasion of New Nepal Samht Year day {Mhapujii), we mhed at the (INBSS) Pdand. Orcgon USA last minute and spent less time in careful editing. Our computer Nepfh %P Puch3h Amaica Orcgon Branch software caused us muble in converting the files fm various subrmttd formats into a unified format. We learn while we work. Constructive are welcome we try Daya R Shakya comments and will to incorporate - suggestions as much as we can. Atedew We have received an enormous st mount of comments, Uma Shrcdha P$.D.Gaurisbankar Manandhar PIID .-m -C-.. Lhwakar Mabajan, Jagadish B Mathema suggestions, appreciations and so forth, (pia IcleI to page 94) Puma Babndur Ranjht including some ~riousconcern abut whether or not this journal Rt&ld Rqmmtatieca should include languages other than English. -

Minorities and Indigenous People Combating Climate Change by Farah Mihlar

briefing Voices that must be heard: minorities and indigenous people combating climate change By Farah Mihlar Introduction communities most affected. As indigenous and minority communities are often politically and socially marginalized From the Batak people of Indonesia to the Karamojong in in their own countries, and in some cases discriminated Africa, those who are least responsible for climate change against, they are unlikely to be consulted on any national or are amongst the worst affected by it. They are often referred international level climate change strategies. to in generic terms such as ‘the world’s poor,’ or ‘vulnerable But the message from the interviews presented here is groups’ by international organizations, the media and the clear: these communities want their voices heard. They United Nations (UN). But these descriptions disguise the want to be part of the climate change negotiations at the fact that specific communities – often indigenous and highest level. minority peoples – are more vulnerable than others. The This briefing paper starts by outlining the key issues – impact of climate change for them is not at some undefined including how communities are affected by climate change point in the future. It is already being felt to devastating and their role at international level discussions. It presents effect. Lives have already been lost and communities are the testimonies, and in conclusion, it considers the way under threat: their unique linguistic and cultural traditions forward for these communities and makes a series of are at risk of disappearing off the face of the earth. recommendations on how their distinct knowledge can be In a statement to mark World Indigenous Day in August harnessed by governments and the UN. -

Mother Tongue Film Festival

2016–2020 Mother Tongue Film Festival Five-Year Report RECOVERING VOICES 1 2 3 Introduction 5 By the Numbers 7 2016 Festival 15 2017 Festival 25 2018 Festival 35 2019 Festival 53 2020 Festival 67 Looking Ahead 69 Appendices Table of Contents View of the audience at the Last Whispers screening, Terrace Theater, Kennedy Center. Photo courtesy of Lena Herzog 3 4 The Mother Tongue Film Festival is a core to the Festival’s success; over chance to meet with guest artists and collaborative venture at the Smithso- time, our partnerships have grown, directors in informal sessions. We nian and a public program of Recov- involving more Smithsonian units and have opened the festival with drum ering Voices, a pan-institutional pro- various consular and academic part- and song and presented live cultural gram that partners with communities ners. When launched, it was the only performances as part of our festival around the world to revitalize and festival of its kind, and it has since events. sustain endangered languages and formed part of a small group of local knowledge. The Recovering Voices and international festivals dedicated We developed a dedicated, bilingual partners are the National Museum of to films in Indigenous languages. (English and Spanish) website for Natural History, the National Museum the festival in 2019, where we stream of the American Indian, and the Cen- Over its five editions, the festival has several works in full after the festival. ter for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. grown, embracing a wide range of And, given the changing reality of our Through interdisciplinary research, audiovisual genres and experiences, world, we are exploring how to pres- community collaboration, and pub- drawing audiences to enjoy screen- ent the festival in a hybrid live/on- lic outreach, we strive to develop ef- ings often at capacity at various ven- line model, or completely virtually, in fective responses to language and ues around Washington, DC. -

Download Tour Dossier

Tour Notes Kenya – Lake Turkana Festival Tour Tour Duration – 9 Days Tour Rating Fitness ●●●○○ | Adventure ●●●●● | Culture ●●●●● | History ●●●○○ | Wildlife ●●●○○ Tour Pace – Busy Tour Highlights ✓ Explore rarely visited regions of northern Kenya, home to a fascinating range of ethnic peoples ✓ Stay at Sabache Camp, wholly owned and run by the Samburu tribe ✓ Hike Ololokwe Sabache for magical sunrise views ✓ Enjoy the opportunity of wildlife viewing in Samburu Reserve ✓ Admire the idyllic desolation of Lake Turkana, the largest desert lake in the world ✓ Immerse yourself in the gathering of flamboyant tribes at the pulsating Turkana Festival Tour Map - Kenya – Lake Turkana Festival Tour Tour Essentials Accommodation: Simple but comfortable accommodation with private bathrooms. Included Meals: Daily breakfast (B), plus lunches (L) and dinners (D) as shown in the itinerary Group Size: Maximum 12 Start Point: Nairobi End Point: Nairobi Transport: 4WD (Airport transfers may not be in 4WD) Country Visited: Kenya Kenya – Lake Turkana Festival Tour Kenya has long been one of the most established safari destinations in Africa, a country rich in wildlife that offers some of the best game viewing on the planet. What few people appreciate is that the country is also incredibly diverse, both ethnically and geographically, with landscapes ranging from lush forest to searing desert and local people characterised by a rich range of origins and traditions. On this trip we venture to the little visited northern regions, an arid land that is home to a number of different ethnic groups including the Samburu, Gabbra, El Moro and Rendille, all of whom adhere to very traditional and unique ways of life. -

Kenya Assessment – Ethiopia's Gibe III Hydropower Project Trip Report (June

Kenya Assessment – Ethiopia’s Gibe III Hydropower Project Trip Report (June - July 2010) Trip Report – June 18 – July 7, 2010 Prepared by Leslie Johnston USAID/Washington, EGAT/ESP USAID/Washington traveled to northern Kenya to meet with stakeholders potentially affected by Ethiopia’s Gibe III hydropower project. This visit is part of USAID’s due diligence efforts under the International Financial Institutions Act, Title XIII, Section 1303(a)(3), to review multilateral development bank (MDB) projects with potential adverse environmental and social impacts. This report summarizes information obtained from meetings with stakeholders in northern Kenya, including meetings with elders and indigenous tribal groups – Gabbra, El molo, Turkana, and Rendille; local government authorities and NGOs. The meetings focused on the relationship of livelihoods to Lake Turkana and their understanding and participation in any other meetings concerning Gibe III. Comments included herein are based on these meetings or documents in the public domain and do not reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government (USG). Not all comments have been substantiated by USAID. General Background Information: Ethiopia’s Gibe III hydropower project, located within the Gibe‐ Omo River Basin, is currently under construction in the middle reach of the Omo River. Gibe III is the third project in a cascade of hydropower development schemes in the basin. The two previous projects are Gilgel Gibe/Gibe I and Gibe II. The Chinese have signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) for the development of the Gibe IV hydropower project downstream of Gibe III, and adjacent to the country’s largest national park, Omo National Park. -

TORBA Provincial Disaster & Climate Response Plan

PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT COUNCIL PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT NATIONAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT OFFICE NATIONAL TORBA ADVISORY BOARD Provincial Disaster & Climate ON CC & DRR Response Plan 2016 Province of TORBA – 2016 PLAN AUTHORIZATION This Plan has been prepared by TORBA Provincial Government Councils in pursuance of Section 11(1) of the National Disaster Act of 2000 and the National Climate Change & Disaster Risk Reduction Policy. ENDORSED BY: _______________________ Date: / / 2016 Mr. Judas Silas Chairperson Provincial Disaster & Climate Change Committee This Plan is approved in accordance with Section 11(2) of the National Disaster Act 2000 and is in-line with the National Climate Change & Disaster Risk Reduction Policy 2015-2030. APPROVED BY: ___________________ Date: / / 2016 Mr. Shadrack Welegtabit Director National Disaster Management Office Ministry Of Climate Change and Disasters ___________________ Date: / / 2016 Mr. David Gibson Director VMGD Office Ministry Of Climate Change and Disasters ___________________ Date: / / 2016 Ms Anna Bule Secretariat National Advisory Board on Climate Change & Disaster Risk Reduction ___________________ Date: / / 2016 Ms Ketty Napwatt Secretary General TORBA Provincial Government i | Province of TORBA – 2016 PREFACE Disaster Risk Management (DRM) Provincial level is a dynamic process. In order to adequately respond to disasters, there must be a comprehensive and coordinated approach between national, provincial and community levels. This plan has been developed to provide guidelines on how to manage different risks in the province, taking into account the effects of the climate change that increase the strength of the hazard and potential impacts of future disasters. This Provincial Disaster & Climate Response Plan provides directive to all agencies on the conduct of Disaster Preparedness and Emergency operations. -

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: a Newar Perspective

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: A Newar Perspective A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Tsukuba In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Public Policy Suwarn VAJRACHARYA 2014 To my mother, who taught me the value in a mother tongue and my father, who shared the virtue of empathy. ii Map-1: Original Nepal (Constituted of 12 districts) and Present Nepal iii Map-2: Nepal Mandala (Original Nepal demarcated by Mandalas) iv Map-3: Gorkha Nepal Expansion (1795-1816) v Map-4: Present Nepal by Ecological Zones (Mountain, Hill and Tarai zones) vi Map-5: Nepal by Language Families vii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents viii List of Maps and Tables xiv Acknowledgements xv Acronyms and Abbreviations xix INTRODUCTION Research Objectives 1 Research Background 2 Research Questions 5 Research Methodology 5 Significance of the Study 6 Organization of Study 7 PART I NATIONALISM AND LANGUAGE POLITICS: VICTIMS OF HISTORY 10 CHAPTER ONE NEPAL: A REFLECTION OF UNITY IN DIVERSITY 1.1. Topography: A Unique Variety 11 1.2. Cultural Pluralism 13 1.3. Religiousness of People and the State 16 1.4. Linguistic Reality, ‘Official’ and ‘National’ Languages 17 CHAPTER TWO THE NEWAR: AN ACCOUNT OF AUTHORS & VICTIMS OF THEIR HISTORY 2.1. The Newar as Authors of their history 24 2.1.1. Definition of Nepal and Newar 25 2.1.2. Nepal Mandala and Nepal 27 Territory of Nepal Mandala 28 viii 2.1.3. The Newar as a Nation: Conglomeration of Diverse People 29 2.1.4. -

Neo-Vernacularization of South Asian Languages

LLanguageanguage EEndangermentndangerment andand PPreservationreservation inin SSouthouth AAsiasia ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 7 Language Endangerment and Preservation in South Asia ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 7 PUBLISHED AS A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION LANGUAGE ENDANGERMENT AND PRESERVATION IN SOUTH ASIA Special Publication No. 7 (January 2014) ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 USA http:/nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I PRESS 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822-1888 USA © All text and images are copyright to the authors, 2014 Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives License ISBN 978-0-9856211-4-8 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4607 Contents Contributors iii Foreword 1 Hugo C. Cardoso 1 Death by other means: Neo-vernacularization of South Asian 3 languages E. Annamalai 2 Majority language death 19 Liudmila V. Khokhlova 3 Ahom and Tangsa: Case studies of language maintenance and 46 loss in North East India Stephen Morey 4 Script as a potential demarcator and stabilizer of languages in 78 South Asia Carmen Brandt 5 The lifecycle of Sri Lanka Malay 100 Umberto Ansaldo & Lisa Lim LANGUAGE ENDANGERMENT AND PRESERVATION IN SOUTH ASIA iii CONTRIBUTORS E. ANNAMALAI ([email protected]) is director emeritus of the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore (India). He was chair of Terralingua, a non-profit organization to promote bi-cultural diversity and a panel member of the Endangered Languages Documentation Project, London. -

West Greenlandic Eskimo & Haida 1. Introduction in This Chapter, We

Chapter 4 The Constitution of FOCUS: West Greenlandic Eskimo & Haida 1. Introduction In this chapter, we introduce West Greenlandic Eskimo and Haida and outline portions of two languages which are associated with the expression of FOCUS. One language will exploit sentence initial position and one, sentence final position. They will also differ in how/whether they wed other semantics with FOCUS, and they will differ in how they associate other semantics with FOCUS. These interplays afford us the opportunity to enrich our conceptuali- zation of FOCUS. 2. West Greenlandic Eskimo West Greenlandic Eskimo (WGE) is a language that places S, O, and V in that order in the most neutral expressions:1 SOXV is clearly the neutral order (Sadock 1984.196) 1 The following is from the webpage of the Alaska Native Language Center (http://www.uaf.edu/anlc/): Although the name “Eskimo” is commonly used in Alaska to refer to all Inuit and Yupik people of the world, this name is considered derogatory in many other places because it was given by non-Inuit people and was said to mean “eater of raw meat.” Linguists now believe that “Eskimo” is derived from an Ojibwa word meaning “to net snowshoes.” However, the people of Canada and Greenland prefer other names. “Inuit,” meaning “people,” is used in most of Canada, and the language is called “Inuktitut” in eastern Canada although other local designations are used also. The Inuit people of Greenland refer to themselves as “Greenlanders” or “Kalaallit” in their language, which they call “Greenlandic” or “Kalaallisut.” Most Alaskans continue to accept the name “Eskimo,” particularly because “Inuit” refers only to the Inupiat of northern Alaska, the Inuit of Canada, and the Kalaallit of Greenland, and is not a word in the Yupik languages of Alaska and Siberia. -

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory: Table of Contents and Section Descriptions 1. Linguistic Resources Academic linguistics articles, reference materials, and online language resources for each BC First Nations language. 2. Language-Specific Resources Practical teaching resources and curriculum identified for each BC First Nations language. 3. Adaptable Resources General curriculum and teaching resources which can be adapted for teaching BC First Nations languages: books, curriculum documents, online and multimedia resources. Includes copies of many documents in PDF format. 4. Language Revitalization Resources This section includes general resources on language revitalization, as well as resources on awakening languages, teaching methods for language revitalization, materials and activities for language teaching, assessing the state of a language, envisioning and planning a language program, teacher training, curriculum design, language acquisition, and the role of technology in language revitalization. 5. Language Teaching Journals A list of journals relevant to teachers of BC First Nations languages. 6. Further Education This section highlights opportunities for further education, training, certification, and professional development. It includes a list of conferences and workshops relevant to BC First Nations language teachers, and a spreadsheet of post‐ secondary programs relevant to Aboriginal Education and Teacher Training - in BC, across Canada, in the USA, and around the world. 7. Funding This section includes a list of funding sources for Indigenous language revitalization programs, as well as a list of scholarships and bursaries available for Aboriginal students and students in the field of Education, in BC, across Canada, and at specific institutions. -

Lynne & Sambo's Trip to Kenya

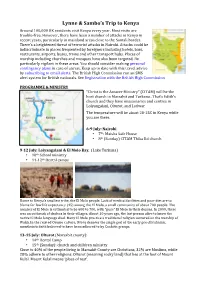

Lynne & Sambo’s Trip to Kenya Around 100,000 UK residents visit Kenya every year. Most visits are trouble-free. However, there have been a number of attacks in Kenya in recent years, particularly in mainland areas close to the Somali border. There’s a heightened threat of terrorist attacks in Nairobi. Attacks could be indiscriminate in places frequented by foreigners including hotels, bars, restaurants, airports, buses, trains and other transport hubs. Places of worship including churches and mosques have also been targeted. Be particularly vigilant in these areas. You should consider making personal contingency plans in case of unrest. Keep up to date with this travel advice by subscribing to email alerts. The British High Commission run an SMS alert system for British nationals. See Registration with the British High Commission PROGRAMME & MINISTRY “Christ is the Answer Ministry” (CITAM) will be the host church in Marsabit and Turkana . That's Edith’s church and they have missionaries and centres in Loiyangalani, Olturot, and Lodwar The temperature will be about 20-25C in Kenya while you are there. 6-9 July: Nairobi • 7th: Maisha Safe House • 8th (Sunday) CITAM Thika Rd church 9-12 July: Loiyangalani & El Molo Bay, (Lake Turkana) • 10th School ministry • 11-12th Dental camps Home to Kenya’s smallest tribe, the El Molo people. Lack of medical facilities and poor diet are to blame for low life expectancy (45) among the El Molo, a small community of about 700 people. The number of El Molo is estimated to be 600 to 700, with “pure” El Molo in their dozens. -

Bhaktapur, Nepal's Cow Procession and the Improvisation of Tradition

FORGING SPACE: BHAKTAPUR, NEPAL’S COW PROCESSION AND THE IMPROVISATION OF TRADITION By: GREGORY PRICE GRIEVE Grieve, Gregory P. ―Forging a Mandalic Space: Bhaktapur, Nepal‘s Cow Procession and the Improvisation of Tradition,‖ Numen 51 (2004): 468-512. Made available courtesy of Brill Academic Publishers: http://www.brill.nl/nu ***Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document Abstract: In 1995, as part of Bhaktapur, Nepal‘s Cow Procession, the new suburban neighborhood of Suryavinayak celebrated a ―forged‖ goat sacrifice. Forged religious practices seem enigmatic if one assumes that traditional practice consists only of the blind imitation of timeless structure. Yet, the sacrifice was not mechanical repetition; it could not be, because it was the first and only time it was celebrated. Rather, the religious performance was a conscious manipulation of available ―traditional‖ cultural logics that were strategically utilized during the Cow Procession‘s loose carnivalesque atmosphere to solve a contemporary problem—what can one do when one lives beyond the borders of religiously organized cities such as Bhaktapur? This paper argues that the ―forged‖ sacrifice was a means for this new neighborhood to operate together and improvise new mandalic space beyond the city‘s traditional cultic territory. Article: [E]very field anthropologist knows that no performance of a rite, however rigidly prescribed, is exactly the same as another performance.... Variable components make flexible the basic core of most rituals. ~Tambiah 1979:115 In Bhaktapur, Nepal around 5.30 P.M. on August 19, 1995, a castrated male goat was sacrificed to Suryavinayak, the local form of the god Ganesha.1 As part of the city‘s Cow Procession (nb.