Schiffman, Harold F. TITLE Language and Society in South Asia. Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rock Arts of Buddhist Caves in Vidarbha (Maharashtra) India

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 9 ~ Issue 3 (2021)pp: 01-09 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Rock Arts of Buddhist Caves in Vidarbha (Maharashtra) India Dr Akash Daulatrao Gedam Asst. Prof. Dept. Applied Sciences & Humanities, Yeshwantrao Chavan College of Engineering, Wanadongari, Hingna Road, Nagpur-441110 Received 02 Mar, 2021; Revised: 12 Mar, 2021; Accepted 14 Mar, 2021 © The author(s) 2021. Published with open access at www.questjournals.org I. INTRODUCTION: Vidarbha (19° 21”N and long 76° 80”E) is an eastern part of Maharashtra state and is outside the Deccan trap area and falls geologically in the Gondwana formation. It is border the state of Madhya Pradesh to the north, Chhattisgarh in the east, Telangana in the south and Marathwada and Khandesh regions of Maharashtra in the west. Situated in central India, Vidarbha has its own rich, cultural and historical background distinct from rest of Maharashtra, Besides in archaeological remains. Nagpur having Archaeological evidence at every part, the Prehistory Branch of the Archaeological Survey of India, Nagpur has reported Middle Palaeolithic and Upper Palaeolithic sites from the district (IAR 2002-03: 145-148). A notable discovery was of a Neolithic celt made on schist (Adam Excavation 1987-1996) a very less countable prehistoric site in situated Vidarbha region. After that early Mauryan and Mauryan activities in this area and majority of sites are belongs to Satavahanas period. We found archaeological evidences ranging from prehistoric period to modern era at every part of Vidarbha and particularly in Nagpur, Chandrapur, Bhandara and Gondia districts which are known to archaeologist for burial of Megalithic people. -

7=SINO-INDIAN Phylosector

7= SINO-INDIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 525 7=SINO-INDIAN phylosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This phylosector comprises 22 sets of languages spoken by communities in eastern Asia, from the Himalayas to Manchuria (Heilongjiang), constituting the Sino-Tibetan (or Sino-Indian) continental affinity. See note on nomenclature below. 70= TIBETIC phylozone 71= HIMALAYIC phylozone 72= GARIC phylozone 73= KUKIC phylozone 74= MIRIC phylozone 75= KACHINIC phylozone 76= RUNGIC phylozone 77= IRRAWADDIC phylozone 78= KARENIC phylozone 79= SINITIC phylozone This continental affinity is composed of two major parts: the disparate Tibeto-Burman affinity (zones 70= to 77=), spoken by relatively small communities (with the exception of 77=) in the Himalayas and adjacent regions; and the closely related Chinese languages of the Sinitic set and net (zone 79=), spoken in eastern Asia. The Karen languages of zone 78=, formerly considered part of the Tibeto-Burman grouping, are probably best regarded as a third component of Sino-Tibetan affinity. Zone 79=Sinitic includes the outer-language with the largest number of primary voices in the world, representing the most populous network of contiguous speech-communities at the end of the 20th century ("Mainstream Chinese" or so- called 'Mandarin', standardised under the name of Putonghua). This phylosector is named 7=Sino-Indian (rather than Sino-Tibetan) to maintain the broad geographic nomenclature of all ten sectors of the linguasphere, composed of the names of continental or sub-continental entities. -

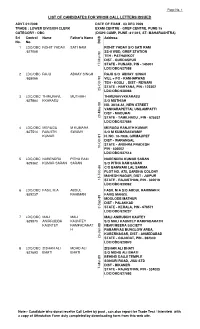

Ldc Final Merit

Page No. 1 LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR WHOM CALL LETTERS ISSUED ADVT-01/2009 DATE OF EXAM - 03 DEC 2009 TRADE : LOWER DIVISION CLERK EXAM CENTRE - GREF CENTRE, PUNE-15 CATEGORY - OBC (DIGHI CAMP, PUNE -411015, ST- MAHARASHTRA) Srl Control Name Father's Name Address No. No. DOB 1 LDC/OBC ROHIT YADAV SATI RAM ROHIT YADAV S/O SATI RAM /627088 SS-II WSD, GREF STATION TEH - PATHANKOT DIST - GURDASPUR STATE - PUNJAB, PIN - 145001 17-Mar-90 LDC/OBC/627088 2 LDC/OBC RAJU ABHAY SINGH RAJU S/O ABHAY SINGH /628066 VILL + PO - KANHARWAS TEH - KOSLI , DIST - REWARI STATE - HARYANA, PIN - 123302 25-Oct-90 LDC/OBC/628066 3 LDC/OBC THIRUNAVL MUTHIAH THIRUNAVVKKARASU /627884 KKARASU S/O MUTHIAH NO. 38/34 A1, NEW STREET VANNARAPETTAI, USILAMPATTI DIST - MADURAI 20-May-88 STATE - TAMILNADU , PIN - 625532 LDC/OBC/627884 4 LDC/OBC MERUGU M KUMARA MERUGU RANJITH KUMAR /627514 RANJITH SWAMY S/O M KUMARASWAMY KUMAR H. NO. 10-7936, GIRMAJIPET DIST - WARANGAL STATE - ANDHRA PRADESH 10-Oct-81 PIN - 506002 LDC/OBC/627514 5 LDC/OBC NARENDRA PITHA RAM NARENDRA KUMAR SARAN /629362 KUMAR SARAN SARAN S/O PITHA RAM SARAN C/O BANWARI LAL SARMA PLOT NO. A75, SARDHA COLONY MAHESH NAGAR, DIST - JAIPUR 15-Feb-86 STATE - RAJASTHAN, PIN - 302019 LDC/OBC/629362 6 LDC/OBC FASIL M.A ABDUL FASIL M A S/O ABDUL RAHIMAN K /629237 RAHIMAN FARIS MANZIL MOOLODE MATHUR DIST - PALAKKAD 2-Sep-89 STATE - KERALA, PIN - 678571 LDC/OBC/629237 7 LDC/OBC MALI MALI MALI ANIRUDDH KAUTEY /629870 ANIRRUDDH KAUNTEY S/O MALI KAUNTEY RAMPADARATH KAUNTEY RAMPADARAT NEAR MEERA SOCIETY H RABARIVAS BUNGLOW AREA, KUBERNAGAR, DIST - AHMEDABAD 23-Jan-88 STATE - GUJARAT, PIN - 382340 LDC/OBC/629870 8 LDC/OBC ZISHAN ALI MOHD ALI ZISHAN ALI BHATI /627693 BHATI BHATI S/O MOHD ALI BHATI BEHIND DAUJI TEMPLE SONGRI ROAD, JISU STD DIST - BIKANER 7-Mar-89 STATE - RAJASTHAN, PIN - 334005 LDC/OBC/627693 Note:- Candidate who donot receive Call Letter by post , can also report for Trade Test / Interview with a copy of Attestation Form duly completed by downloading form from this web site. -

High Vowel Fricativization As an Areal Feature of the Northern Cameroon Grassfields

High vowel fricativization as an areal feature of the northern Cameroon Grassfields Matthew Faytak WOCAL 8, | August 23, 2015 Overview High vowel fricativization is an areal or contact feature of the northern Grassfields, which carries implications for Niger-Congo reconstructions 1. What is (not) a fricativized vowel? 2. Where are they (not)? 3. Why is this interesting? Overview High vowel fricativization is an areal or contact feature of the northern Grassfields, which carries implications for Niger-Congo reconstructions 1. What is (not) a fricativized vowel? 2. Where are they (not)? 3. Why is this interesting? Fricative vowels Vowels with a fricative-like supralaryngeal constriction, which may or may not consistently result in audible fricative noise Not intended to encompass: • Devoiced or voiceless vowels Smith (2003) • Pre-/post-aspirated vowels Helgason (2002) Mortensen (2012) • Articulatory overlap at high speech rate • Wall noise sources in high vowels Shadle (1990) Prior mention Vowels that do fit one or both of the given definitions: • Apical vowels in Chinese Lee (2005) Feng (2007) Lee-Kim (2014) • Viby-i, G¨oteborges-i, etc. in Swedish Holmberg (1976) Engstrand et al. (2000) Sch¨otzet al. (2011) • Fricative vowels in Bantoid Medjo Mv´e(1997) Connell (2007) Articulatory evidence of constriction Olson and Meynadier (2015) Articulatory evidence of constriction z v " " High vowel fricativization (HVF) Fricative vowels arise from normal high vowels /i u/, often in tandem with raising of the next-lowest vowels Faytak (2014) i u e o i -

Uhm Phd 9519439 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality or the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106·1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521-0600 Order Number 9519439 Discourses ofcultural identity in divided Bengal Dhar, Subrata Shankar, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1994 U·M·I 300N. ZeebRd. AnnArbor,MI48106 DISCOURSES OF CULTURAL IDENTITY IN DIVIDED BENGAL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DECEMBER 1994 By Subrata S. -

Tibetan Vwa 'Fox' and the Sound Change Tibeto

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 29.2 — October 2006 TIBETAN VWA ‘FOX’ AND THE SOUND CHANGE TIBETO-BURMAN *WA > TIBETAN O Nathan W. Hill Harvard University Paul Benedict (1972: 34) proposed that Tibeto-Burman medial *-wa- regularly leads to -o- in Old Tibetan, but that initial *wa did not undergo this change. Because Old Tibetan has no initial w-, and several genuine words have the rhyme -wa, this proposal cannot be accepted. In particular, the intial of the Old Tibetan word vwa ‘fox’ is v- and not w-. འ Keywords: Old Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, phonology. 1. INTRODUCTION The Tibetan word vwa ‘fox’ has received a certain amount of attention for being an exception to the theory that Tibeto-Burman *wa yields o in Tibetan1. The first formulation of this sound law known to me is Laufer’s statement “Das Barmanische besitzt nämlich häufig die Verbindung w+a, der ein tibetisches [sic] o oder u entspricht [Burmese namely frequently has the combination w+a, which corresponds to a Tibetan o or u]” (Laufer 1898/1899: part III, 224; 1976: 120). Laufer’s generalization was based in turn upon cognate sets assembled by Bernard Houghton (1898). Concerning this sound change, in his 1972 monograph, Paul Benedict writes: “Tibetan has initial w- only in the words wa ‘gutter’, wa ‘fox’ and 1 Here I follow the Wylie system of Tibetan transliteration with the exception that the letter (erroneously called a-chung by some) is written in the Chinese fashion འ as <v> rather than the confusing <’>. On the value of Written Tibetan v as [ɣ] cf. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 10:48:31PM Via Free Access

journal of language contact 11 (2018) 71-112 brill.com/jlc The Development of Phonological Stratification: Evidence from Stop Voicing Perception in Gurindji Kriol and Roper Kriol Jesse Stewart University of Saskatchewan [email protected] Felicity Meakins University of Queensland [email protected] Cassandra Algy Karungkarni Arts [email protected] Angelina Joshua Ngukurr Language Centre [email protected] Abstract This study tests the effect of multilingualism and language contact on consonant perception. Here, we explore the emergence of phonological stratification using two alternative forced-choice (2afc) identification task experiments to test listener perception of stop voicing with contrasting minimal pairs modified along a 10-step continuum. We examine a unique language ecology consisting of three languages spo- ken in Northern Territory, Australia: Roper Kriol (an English-lexifier creole language), Gurindji (Pama-Nyungan), and Gurindji Kriol (a mixed language derived from Gurindji and Kriol). In addition, this study focuses on three distinct age groups: children (group i, 8>), preteens to middle-aged adults (group ii, 10–58), and older adults (group iii, 65+). Results reveal that both Kriol and Gurindji Kriol listeners in group ii contrast the labial series [p] and [b]. Contrarily, while alveolar [t] and velar [k] were consis- tently identifiable by the majority of participants (74%), their voiced counterparts ([d] and [g]) showed random response patterns by 61% of the participants. Responses © Jesse Stewart et al., 2018 | doi 10.1163/19552629-01101003 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc license at the time of publication. -

Trubetzkoy Final

Chapman, S. & Routledge, P. (eds) (2005) Key Thinkers in Linguistics and the Philosophy of Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Pp 267-268. Trubetzkoy, N.S. (Nikolai Sergeevich); (b. 1890, d. 1938; Russian), lecturer at Moscow University (1915-1916), Rostov-on-Don University (1918), Sofia University (1920-1922), finally professor of Slavic linguistics at Vienna University (1922-1938). One of the founding fathers of phonology and a key theorist of the Prague School. (See Also: *Jakobson, Roman; *Martinet, André). Trubetzkoy’s life was blighted by persecution. Born in Moscow of aristocratic, academic parents, Trubetzkoy (whose names have been transliterated variously) was a prince, and, after study and an immediate start to a university career in Moscow, he was forced to flee by the 1917 revolution; he subsequently also had to leave Rostov and Sofia. On settling in Vienna, he became a geographically distant member of the Prague Linguistic Circle. It is at times difficult to tease his ideas apart from those of his friend *Jakobson, who ensured that his nearly-finished Grundzüge der Phonologie (1939) was posthumously published. Trubetzkoy had previously published substantial work in several fields, but this was his magnum opus. It summarised his previous phonological work and stands now as the classic statement of Prague School phonology, setting out an array of phonological ideas, several of which still characterise debate on phonological representations. Through it, the publications which preceded it, his work at conferences and general enthusiastic networking, Trubetzkoy was crucial in the development of phonology as a discipline distinct from phonetics, and the change in phonological focus from diachrony to synchrony. -

Paleomagnetic and Geochronological Studies of the Mafic Dyke Swarms Of

Precambrian Research 198–199 (2012) 51–76 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Precambrian Research journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/precamres Paleomagnetic and geochronological studies of the mafic dyke swarms of Bundelkhand craton, central India: Implications for the tectonic evolution and paleogeographic reconstructions a,∗ a b a c Vimal R. Pradhan , Joseph G. Meert , Manoj K. Pandit , George Kamenov , Md. Erfan Ali Mondal a Department of Geological Sciences, University of Florida, 241 Williamson Hall, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA b Department of Geology, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur 302004, Rajasthan, India c Department of Geology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh 202002, India a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: The paleogeographic position of India within the Paleoproterozoic Columbia and Mesoproterozoic Received 12 July 2011 Rodinia supercontinents is shrouded in uncertainty due to the paucity of high quality paleomagnetic Received in revised form 6 November 2011 data with strong age control. New paleomagnetic and geochronological data from the Precambrian mafic Accepted 18 November 2011 dykes intruding granitoids and supracrustals of the Archean Bundelkhand craton (BC) in northern Penin- Available online 28 November 2011 sular India is significant in constraining the position of India at 2.0 and 1.1 Ga. The dykes are ubiquitous within the craton and have variable orientations (NW–SE, NE–SW, ENE–WSW and E–W). Three dis- Keywords: tinct episodes of dyke intrusion are inferred from the paleomagnetic analysis of these dykes. The older Bundelkhand craton, Mafic dykes, Central ◦ NW–SE trending dykes yield a mean paleomagnetic direction with a declination = 155.3 and an incli- India, Paleomagnetism, Geochronology, ◦ ◦ − Ä ˛ Paleogeography nation = 7.8 ( = 21; 95 = 9.6 ). -

Language and Geometry a Method for Comparing the Genealogical and Structural Relatedness Between Pairs of European Languages

4 Journal for EuroLinguistiX 11 (2014): 4-13 Jacques François Language and Geometry A Method for Comparing the Genealogical and Structural Relatedness between Pairs of European Languages Abstract In the second half of 19th century, two German linguists, August Schleicher and Johannes Schmidt, worked out a method of genealogical comparison of the Indo-European languages which crucially rested on inflectional morphology and phonology (so-called Stammbaum hypothesis by Schleicher) supplemented by wave-like spreading (so-called wave-hypothesis by Schmidt) of such properties amongst geographically neighbouring languages. First, this method is applied to four European languages: Dutch, English, French and German. Next, a list of 18 structural properties of the four languages is collected in order to assess the structural relatedness of each pair of languages. The two resulting charts turn out to be similar concerning the proximity between Dutch vs. German, but quite disparate concerning the latter vs. English and French. The structural chart is insightful, but weighting the collected structural properties (on the basis of criteria to be justified) might generate a differently shaped chart. Sommaire Dans la seconde moitié du 19e siècle, deux linguistes allemands, August Schleicher et Johannes Schmidt, ont élaboré une méthode de comparaison généalogique des langues indo-européennes essentiellement basée sur la morphologie flexionnelle et la phonologie (hypothèse du Stammbaum de Schleicher) complétée par une dissémination ‘ondulatoire’ (hypothèse de Schmidt) de propriétés de ce type entre des langues géographiquement voisines. En premier lieu, cette méthode est appliquée à quatre langues européennes : allemand, anglais, français et néerlandais. Ensuite, une liste de 18 propriétés structurales des quatre langues est établie afin de mesurer la proximité structurale entre celles-ci. -

Requiem-For-Our-Times-E-Book.Pdf

Like those in his earlier book, The Losers Shall Inherit the World, these articles too were first published in Frontier and deal with current socio-economic-cultural issues of a diverse range of topics. These include, Sanskrit, Hinduism, Bhimsen Joshi, Education Manifesto, Euthanasia, Small States, Population, Cities, Peak Oil and the Politics of Non-Violence. There are also two small articles dealing with the Passion (Christ’s suffering at the Cross) and the concept of Liberation. ‘If a political activist can be defined as a person who is not only trying to promote the interests of his own particular group or class but trying, generally speaking, to create a better world, then she must first have a good understanding of the state of the present-day world. And then Vijayendra’s article (Yugant in this book) is a must-read for her, because it is an excellent short introduction to the subject.’ Saral Sarkar, author of Eco-Socialism You can read this book online or download a copy at www.peakoilindia.org REQUIEM FOR OUR TIMES T. Vijayendra SANGATYA REQUIEM FOR OUR TIMES Author: T. Vijayendra Copy Editor: Sajai Jose Year: 2015 Price: Rs. 100 Copies: 500 L Copy Left: All Rights Reversed Publishers: Sangatya Sahitya Bhandar Post Nakre, Taluk Karkala, Dist. Udupi Karnataka 576 117 Phone: 08258 205340 Email: [email protected] Blog: t-vijayendra.blogspot.com SCRIBD: vijayendra tungabhadra Mobile: +91 94907 05634 For Copies: Manchi Pustakam 12-13-439, St. No. 1 Tarnaka, Secunderabad 500017 Email: [email protected] Mobile: +91 73822 97430 Layout and Printing: Charita Impressions Azamabad, Hyderabad - 500 020. -

Depicting the Indian Diaspora

THE INDIAN DIASPORA & AN INDIAN IN COWBOY COUNTRY © Pradeep Anand Harvard University, April 24, 2007 www.pradeepanand.com When the South Asian organizers at Harvard University told me that the audience was interested in discussing how authors depict the Indian Diaspora, I was confronted with a topic that I had not thought about, ever. I had not set out to create a work of fiction about the Diaspora and I had never seen my book, An Indian in Cowboy Country, through those lenses before. When forced to think about this topic, my knee-jerk reaction was to be conventional and think about the global Indian Diaspora – from India to Fiji, to West Indies, to Yuba City, to British Columbia, to the countries of the Indian Ocean, to Great Britain, Canada, and the United States. My mind immediately went to the big, macro historical picture, with all these turbid rivers of brown-skinned workforce flowing out of the country, migrating to unknown destinations. I saw these huge torrents flowing out of India and I was a particle in it. And then something made me look at my own family history. At first blush, it seemed like I was one of the seeds of the global Indian Diaspora for just one generation. But then I recognized a reality. My family uprooted itself three generations ago, when my grandfather moved to Bangalore. That’s where my father grew up and then, he, in his turn, moved to Bombay. I grew up in Bombay and then I moved from Bombay to Texas. To put this in perspective, my family moved from a Tamil- speaking region to a Kannada-speaking one, then to a Marathi/Gujarati-speaking one, and finally to an English speaking one (at least for now).