Edge of the Knife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Reid Gallery Re-Opens ANd Commemorates 100Th Anniversary of One of Canada's Most Renowned Indigenous Artists In

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 9, 2020 Bill Reid Gallery Re-opens and Commemorates 100th Anniversary of One of Canada’s Most Renowned Indigenous Artists in – To Speak With a Golden Voice – Exhibition brings fresh perspective to Bill Reid’s legacy with rarely seen artworks and new commissions by Northwest Coast artists inspired by his life and practice VANCOUVER, BC — Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art re-opens the gallery and celebrates the milestone centennial birthday of Bill Reid (1920–1998) with an exhibition about his extraordinary life and legacy, To Speak With a Golden Voice, from July 16, 2020 to April 11, 2021. Guest curated by Gwaai Edenshaw — considered to be Reid’s last apprentice — the group exhibition includes rarely seen treasures by Reid and works from artists such as Robert Davidson and Beau Dick. Tracing the iconic Haida artist’s lasting influence, two new artworks by contemporary artist Cori Savard (Haida) and singer-songwriter Kinnie Starr (Mohawk/Dutch/German//Irish) will be created for this highly anticipated exhibition. “Bill Reid was a master goldsmith, sculptor, community activist, and mentor whose lasting legacy and influence has been cemented by his fusion of Haida traditions with his own modernist aesthetic,” says Edenshaw. “Just about every Northwest Coast artist working today has a connection or link to Reid. Before he became renowned for his artwork, he was a CBC radio announcer recognized for his memorable voice — in fact, one of Reid’s many Haida names was Kihlguulins, or ‘golden voice.’ His role as a public figure helped him become a pivotal force in the resurgence of Northwest Coast art, introducing the world to its importance and empowering generations of artists.” Reid was born in Victoria, BC, to a Haida mother and an American father with Scottish-German roots. -

Mother Tongue Film Festival

2016–2020 Mother Tongue Film Festival Five-Year Report RECOVERING VOICES 1 2 3 Introduction 5 By the Numbers 7 2016 Festival 15 2017 Festival 25 2018 Festival 35 2019 Festival 53 2020 Festival 67 Looking Ahead 69 Appendices Table of Contents View of the audience at the Last Whispers screening, Terrace Theater, Kennedy Center. Photo courtesy of Lena Herzog 3 4 The Mother Tongue Film Festival is a core to the Festival’s success; over chance to meet with guest artists and collaborative venture at the Smithso- time, our partnerships have grown, directors in informal sessions. We nian and a public program of Recov- involving more Smithsonian units and have opened the festival with drum ering Voices, a pan-institutional pro- various consular and academic part- and song and presented live cultural gram that partners with communities ners. When launched, it was the only performances as part of our festival around the world to revitalize and festival of its kind, and it has since events. sustain endangered languages and formed part of a small group of local knowledge. The Recovering Voices and international festivals dedicated We developed a dedicated, bilingual partners are the National Museum of to films in Indigenous languages. (English and Spanish) website for Natural History, the National Museum the festival in 2019, where we stream of the American Indian, and the Cen- Over its five editions, the festival has several works in full after the festival. ter for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. grown, embracing a wide range of And, given the changing reality of our Through interdisciplinary research, audiovisual genres and experiences, world, we are exploring how to pres- community collaboration, and pub- drawing audiences to enjoy screen- ent the festival in a hybrid live/on- lic outreach, we strive to develop ef- ings often at capacity at various ven- line model, or completely virtually, in fective responses to language and ues around Washington, DC. -

TIFF Premiere: Sgaawaay K'uuna, the First Feature Film About the Haida People

Academic rigour, journalistic flair TIFF premiere: Sgaawaay K'uuna, the first feature film about the Haida people September 5, 2018 7.27pm EDT High school honour roll student Trey Arnold Rorick acts in the ‘Edge of the Knife.’ Rorick also works as a Cultural Interpreter at the K_ay Ilnagaay Haida Heritage Center. Facebook TIFF premiere: Sgaawaay K'uuna, the first feature film about the Haida people September 5, 2018 7.27pm EDT Sgaawaay K'uuna (Edge of the Knife), premiering at the Toronto International Film Author Festival, is the first feature film about the Haida people and in the Haida language. The mystery-thriller, directed by Gwaai Edenshaw and Helen Haig-Brown, started as a collaboration between myself at the University of British Columbia (UBC), the Inuit film production company Kingulliit and the Council of the Haida Nation (CHN). Leonie Sandercock Professor, University of British Columbia We hope the film will be a catalyst for language revitalization as well as community economic development. In 2012, fewer than one per cent of the Haida were fluent in the Haida language and most of those were over the age of 70, so the language was regarded as in crisis. Edge of the Knife emerged out the results of a community planning process our students had been involved in at Skidegate a year earlier, a year of community engagement and envisioning Haida hopes and dreams. The top three priorities identified by the Skidegate community were language revitalization, the creation of jobs that would keep youth on Haida Gwaii instead of moving to Vancouver and protecting the lands and waters of Haida Gwaii through sustainable economic development. -

Building Resilience Through Partnership

BUILDING RESILIENCE THROUGH PARTNERSHIP 2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 HIGHLIGHTS 9 ACHIEVEMENTS 11 ABOUT US 14 MESSAGES MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION 18 AND ANALYSIS INDUSTRY AND 19 ECONOMIC CONDITIONS CORPORATE 28 PLAN DELIVERY ATTRACT ADDITIONAL FUNDING 29 AND INVESTMENT EVOLVE OUR FUNDING 33 ALLOCATION APPROACH OPTIMIZE OUR 45 OPERATIONAL CAPABILITY ENHANCE THE VALUE 50 OF THE “CANADA” AND “TELEFILM” BRANDS 57 FINANCIAL REVIEW 64 RISK MANAGEMENT CORPORATE SOCIAL 66 RESPONSIBILITY 70 TALENT FUND 81 GOVERNANCE FINANCIAL 95 STATEMENTS ADDITIONAL 117 INFORMATION TELEFILM CANADA / 2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT 1 The Canadian industry and audiences embraced female voices and HIGHLIGHTS Indigenous expression in fiscal year 2019-2020. Telefilm remained committed to greater representation in the films we support and to bringing Canadian creativity to the world. LOOKING TO THE FUTURE, our vision is for Telefilm and Canada to strengthen their role of Partner of Choice—creating and building ties, expanding opportunities and deepening impact. BRINGING CANADIAN CREATIVITY TO THE WORLD The Canada-Norway coproduction THE BODY REMEMBERS WHEN THE WORLD BROKE OPEN, directed by KATHLEEN HEPBURN and ELLE-MÁIJÁ TAILFEATHERS, received praise around the world— premiering at the Berlin Film Festival in 2019, selected as “REMARKABLE” a New York Times Critic’s Pick and being called “remarkable” by the Los Angeles Times. The film went on to be picked up ★★★★★ by Ava DuVernay’s ARRAY releasing for U.S and international. levelFilm distributed the film in Canada, while Another World LOS ANGELES TIMES Entertainment handled Norway. TELEFILM CANADA / 2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2 HIGHLIGHTS BRINGING CANADIAN CREATIVITY TO THE WORLD MONIA CHOKRI’s debut feature filmLA FEMME DE WINNER MON FRÈRE (A Brother’s Love), which she both wrote COUP DE CŒUR AWARD and directed, premiered at the Cannes Film Festival CANNES opening the Un Certain Regard section, bringing home FILM FESTIVAL the jury’s Coup de Cœur award. -

Cabin Fever: Free Films for Kids! The

January / February 2019 Canadian & International Features NEW WORLD DOCUMENTARIES special Events THE GREAT BUSTER CABIN FEVER: FREE FILMS FOR KIDS! www.winnipegcinematheque.com January 2019 TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 1 2 3 4 5 6 closed: New Year’s Day Roma / 7 pm Roma / 7 pm & 9:30 pm Roma / 7 pm & 9:30 pm Roma / 3 pm & 7 pm cabin fever: Coco 3D / 3 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Canada’s Top Ten: Anthropocene: Anthropocene: The Human Epoch / 9:30 pm The Human Epoch / 5 pm Roma / 7 pm 8 9 10 11 12 13 The Last Movie / 7 pm Roma / 7 pm Jean-Pierre Melville: Black Lodge: Secret Cinema Roma / 2:30 pm cabin fever: The Big Bad Dial Code Santa Claus / 9 pm Le samouraï / 7 pm with the Laundry Room / 7 pm Jean-Pierre Melville: Fox and Other Tales… / 3 pm Roma / 9 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Léon Morin, Priest / 5 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Anthropocene: Canada’s Top Ten: Anthropocene: The Human Epoch / 7 pm Anthropocene: The Human Epoch / 5 pm Roma / 9 pm The Human Epoch / 7:15 pm Genesis / 7 pm Genesis / 9 pm 15 16 17 18 19 20 The Last Movie / 7 pm Jean-Pierre Melville: Canada’s Top Ten: Jean-Pierre Melville: The Great Buster / 3 pm & 7 pm cabin fever: Buster Keaton’s Dial Code Santa Claus / 9 pm Léon Morin, Priest / 7 pm Anthropocene: Le doulos / 7 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Classic Shorts / 3 pm The Human Epoch / 7 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Anthropocene: The Great Buster / 5 pm Roads in February / 9 pm Anthropocene: The Human Epoch / 5 pm Jean-Pierre Melville: The Human Epoch / 9 pm Roads in February / 9 pm Le samouraï / 7 pm 22 23 24 25 26 27 The Last -

Sovereign Nation Press Release 2019

PRESS RELEASE 12.7.19 Immediate release Pitt Rivers Museum collaborate on Sovereign Nation: an international exchange between Haida artist Gwaai Edenshaw from Haida Gwaii, Canada and Anna Glynn and Robin Colyer from Flintlock Theatre The Pitt Rivers Museum are delighted to announce our collaboration with Oxford company Flintlock Theatre in support of their international exchange with Gwaai Edenshaw: a renowned indigenous Haida artist from the Haida Gwaii archipelago off the west coast of Canada. Supported by the New Conversations fund (provided by Farnham Maltings, the High Commission of Canada in the U.K and the British Council) and Arts Council England, the exchange centres on the Pitt Rivers Museum’s Star House Pole, which was purchased from the Haida people in 1901. In July 2019, Anna and Robin from Flintlock will visit the original site of the Star House Pole in the village of Old Masset and in March 2020, Gwaai will visit Oxford. During their visits, the artists will work with local people to explore Canada’s and the UK’s shared relationship to colonialism including, a weekend of workshops in Oxford for students from all six city state schools. Throughout the exchange, the artists will record their experiences via a series of short films that will be on display at the Pitt Rivers later in the year. The project was one of nine selected from over 100 applications. Janice Charette, High Commissioner of Canada in the UK, announced “Canada is proud to support these artistic collaborations between our country and the UK and we are especially pleased to be able to give some of these arts organisations their first chance to share their work internationally.” Gavin Stride, Director of the Maltings, said: “Our involvement in this programme is made possible through support and investment of Arts Council of England. -

Keeping Haida Alive Through Film and Drama

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 20 Collaborative Approaches to the Challenge of Language Documentation and Conservation: Selected papers from the 2018 Symposium on American Indian Languages (SAIL) ed. by Wilson de Lima Silva and Katherine Riestenberg, p.107-122 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ 8 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24935 Keeping Haida alive through film and drama Frederick White Slippery Rock University The Haida language, of the northwest coast of Canada and Southern Alaska, has been endangered for most of the 20th century. Historically, orthography has been a difficult issue for anyone studying the language, since no standardized orthography existed. In spite of the orthographical issues, current efforts in Canada at revitalizing Haida lan- guage and culture have culminated in the theatrical production of Sinxii’gangu, a tradi- tional Haida story dramatized and performed completely in Haida. The most recent effort is Edge of the Knife, a film about a Haida man transforming into a gaagiid (wild man) as a result of losing a child. The story line addresses his restoration back into the community, and as a result, affords not just a resource for two Haida dialects, but also for history and culture. With regards to language, actors participated in two weeks of immersion to prepare and struggled through issues with Haida pronunciation during filming. Using the Haida language exclusively, not just in oral narratives (though there are some in the drama and the film) but in actual dialogue, provides learners with great context for developing strategies for pronunciation and conversation rather than only learning and hearing lexical items and short phrases. -

Indigenous-Film-Programme-2020-21

1 REEL CANADA Uniting our Nations through Film WHO WE ARE REEL CANADA is a charitable organization whose mission is to introduce new audiences to the power and diversity of Canadian film and engage them in a conversation about identity and culture. Showcasing works by Indigenous filmmakers from Canada is an integral part of that mission. Our travelling film festival has reached over a million students – and it just keeps growing! WHAT WE DO LESSON PLANS AND Now entering our 16th season, we offer several programmes for students. And, through National RESOURCES Canadian Film Day (NCFD), we also bring an annual With a track record of thousands of successful school celebration of film to all Canadians. screenings, we can give you effective tools to get your colleagues and students excited about your Our Educational Programmes serve anywhere from event, and work with you to create a festival that will a single class to a whole school. They all incorporate resonate with your community. incredible work made by Indigenous filmmakers, and all of them are absolutely free of charge. We offer: • Film-specific lesson plans orf all feature-length Our Films in Our Schools: for more than 14 years, films in this programme we have helped teachers and students organize over 3,000 screenings of Canadian films • Lesson plans for Indigenous and Native studies courses Welcome to Canada: introducing new Canadians to Canadian film and culture through festival events • Lesson plans about Canadian film and torytellings designed specifically for English-language -

New Films from Canada March 7 – 10, 2019 Ifc Center, New York

NEW FILMS FROM CANADA MARCH 7 – 10, 2019 IFC CENTER, NEW YORK With the support of CANADA NOW 2019 Look up. Way up. Up above that distant 49th parallel. Soon you will begin to see the swirling illuminations of those northern cinematic lights: Canada Now 2019 is here. Yes, your Canadian neighbours are again coming south, bringing tales of restless youth, ancient indigenous stories of tragedy and healing, compelling personal dramas about reinventing our world with the power of our imaginations, plus a trio of riveting, dramatic documentaries about the global environmental crisis, war crimes in Europe, and the struggle for civil rights in the United States of America. This latest Canada Now selection includes daring and impressive works by both veteran fi lmmakers and new Canadian visions by emerging directorial talents. The 2019 Canada Now showcase celebrates the independent creative spirit that has always been a hallmark of Canadian cinema. Follow us on Facebook at @CanadaNowFilm www.CanadaNowFestival.com CANADA NOW is presented by Telefi lm Canada in partnership with the Consulate General of Canada in New York City and with the support of Air Canada. Directors of the CANADA NOW fi lms will be present at screenings for Q & A. Anthropocene: The Human Epoch THURSDAY, MARCH 7, 7:00 PM FRIDAY, MARCH 8, 7:00 PM ANTHROPOCENE: THE HUMAN EPOCH HUGH HEFNER’S AFTER DARK: Directors: Jennifer Baichwal, Nicholas de Pencier, Edward Burtynsky SPEAKING OUT IN AMERICA U.S. Distributor: Kino Lorber in association with Kanopy Director: Brigitte Berman 2018 | 87 MINUTES | ENGLISH 2018 | 101 MINUTES | ENGLISH Four years in the making, Anthropocene: The Human Epoch is a visually arresting From Brigitte Berman, Oscar winning director of Artie Shaw: Time Is All You’ve Got (1985), cinematic rumination on humanity’s recent, rapacious technological transformation of comes this remarkable documentary of one of America’s most influential and controversial the Earth. -

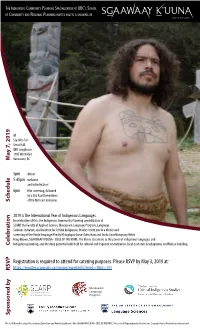

M Ay 7, 2019 C Elebration Sp Onsored B Y Registration Is Required To

THE INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY PLANNING SPECIALIZATION AT UBC’S SCHOOL OF COMMUNITY AND REGIONAL PLANNING INVITES YOU TO A SHOWING OF EDGE OF THE KNIFE at Sty-Wet-Tan Great Hall, UBC Longhouse 1985 West Mall May 7, 2019 May Vancouver, BC A FILM BY GWAAI EDENSHAW & HELEN HAIGBROWN 5pm dinner COUNCIL OF THE HAIDA NATION NIIJANG XYAALAS PRODUCTIONS PRODUCTION STARRING TYLER YORK WILLIAM RUSS ADEANA YOUNG AND TREY RORICK DELORES CHURCHILL XIILA GUUJAAW GWAAGANAD DIANE BROWN KINNIE STARR ATHENA THENY SARAH HEDAR SANDY COCHRANE JONATHAN FRANTZ ZACHARIAS KUNUK STEPHEN GROSSE JONATHAN FRANTZ 5:45pm welcome GWAAI EDENSHAW JAALEN EDENSHAW GRAHAM RICHARD LEONIE SANDERCOCK and introductions GWAAI EDENSHAW HELEN HAIGBROWN 6pm film screening, followed by a Q & A with members Schedule of the film cast and crew 2019 is The International Year of Indigenous Languages. In celebration of this, the Indigenous Community Planning specialization at SCARP, the Faculty of Applied Science, Musqueam Language Program, Language Sciences Initiative, and Institute for Critical Indigenous Studies invite you to a dinner and screening of the Haida language film by Hluugitgaa Gwaai Edenshaw and Jaada Gyaahlangnaay Helen Haig-Brown, SGAAWAAY K’UUNA - EDGE OF THE KNIFE. The film is testament to the power of Indigenous languages and Celebration Indigenous planning, and the deep potential both hold for cultural and linguistic revitalization, local economic development, and Nation-building. Registration is required to attend for catering purposes. Please RSVP by May 3, 2019 at: https://register.scarp.ubc.ca/civicrm/event/info?reset=1&id=131 RSVP Musqueam Language Program Sponsored by Sponsored Photo: William Russ plays Kwa in Gwaai Edenshaw and Helen Haig-Brown’s film SGAAWAAY K’UUNA -EDGE OF THE KNIFE. -

Go Haida Gwaii

The name of this publication, This is Haida Gwaii, is followed by the Xaad Kil word – Kaats’ii hla. The word is a response to a knock on the door – come on in! This acknowledges a guest’s presence and welcomes them into the house, and that’s what this publication is – an acknowledgment and welcome to you. Council of the Haida Nation @CHN_HaidaNation @CHN_HaidaNation Haida Gwaii Tourism @HGTourism @GoHaidaGwaii The Hl'yaalan Solstice Pole. Photo — Marcus Paladino Editor SIMON DAVIES Copyright © Council of the Haida Nation | Go Haida Gwaii | 2020 Contributors JASKWAAN BEDARD, VALINE BROWN, All artworks © the artists GAAD GAS RAVEN RYLAND, GRAHAM RICHARD, All texts © the authors ANDREW HUDSON, RHONDA LEE MCISAAC, BENG FAVREAU, All images © the photographers and/or holding institutions HILANG JAAD XYALAA LESLIE BROWN, DONALD 'DUFFY' EDGARS, K'AAJUU G'AAYA GREGORY N. WILLIAMS, JON THORPE, MARCUS PALADINO, NESTAQANA JAGS BROWN, FLAVIEN MABIT, All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, OWEN PERRY, GREGORY GOULD AND DESTINATION BC stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher, Advertising Management ALANAH MOUNTIFIELD, JANINE NORTH the Council of the Haida Nation | Go Haida Gwaii Designer | Illustrator JENNIFER BAILEY Want to advertise in This is Haida Gwaii? Contact [email protected] or call 250-559-8050 elcome to Haida Gwaii, you show your self-respect by coming. Haawa for Wfollowing your heart and accepting the pull of our homeland. Whether you have arrived by sea or air you are meant to be here, right now, as our guest. -

Reference Guide This List Is for Your Reference Only

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA ACT OF THE HEART BLACKBIRD 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / 2012 / Director-Writer: Jason Buxton / 103 min / English / PG English / 14A A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a Sean (Connor Jessup), a socially isolated and bullied teenage charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest conductor goth, is falsely accused of plotting a school shooting and in her church choir. Starring Geneviève Bujold and Donald struggles against a justice system that is stacked against him. Sutherland. BLACK COP ADORATION ADORATION 2017 / Director-Writer: Cory Bowles / 91 min / English / 14A 2008 / Director-Writer: Atom Egoyan / 100 min / English / 14A A black police officer is pushed to the edge, taking his For his French assignment, a high school student weaves frustrations out on the privileged community he’s sworn to his family history into a news story involving terrorism and protect. The film won 10 awards at film festivals around the invites an Internet audience in on the resulting controversy. world, and the John Dunning Discovery Award at the CSAs. With Scott Speedman, Arsinée Khanjian and Rachel Blanchard. CAST NO SHADOW 2014 / Director: Christian Sparkes / Writer: Joel Thomas ANGELIQUE’S ISLE Hynes / 85 min / English / PG 2018 / Directors: Michelle Derosier (Anishinaabe), Marie- In rural Newfoundland, 13-year-old Jude Traynor (Percy BEEBA BOYS Hélène Cousineau / Writer: James R.