Transportation Research Record No. 1441, Nonmotorized Transportation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

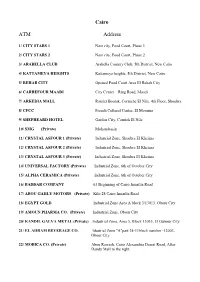

Cairo ATM Address

Cairo ATM Address 1/ CITY STARS 1 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 1 2/ CITY STARS 2 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 2 3/ ARABELLA CLUB Arabella Country Club, 5th District, New Cairo 4/ KATTAMEYA HEIGHTS Kattameya heights, 5th District, New Cairo 5/ REHAB CITY Opened Food Court Area El Rehab City 6/ CARREFOUR MAADI City Center – Ring Road, Maadi 7/ ARKEDIA MALL Ramlet Boulak, Corniche El Nile, 4th Floor, Shoubra 8/ CFCC French Cultural Center, El Mounira 9/ SHEPHEARD HOTEL Garden City, Cornish El Nile 10/ SMG (Private) Mohandessin 11/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 1 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 12/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 2 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 13/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 3 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 14/ UNIVERSAL FACTORY (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 15/ ALPHA CERAMICA (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 16/ BADDAR COMPANY 63 Beginning of Cairo Ismailia Road 17/ ABOU GAHLY MOTORS (Private) Kilo 28 Cairo Ismailia Road 18/ EGYPT GOLD Industrial Zone Area A block 3/13013, Obour City 19/ AMOUN PHARMA CO. (Private) Industrial Zone, Obour City 20/ KANDIL GALVA METAL (Private) Industrial Zone, Area 5, Block 13035, El Oubour City 21/ EL AHRAM BEVERAGE CO. Idustrial Zone "A"part 24-11block number -12003, Obour City 22/ MOBICA CO. (Private) Abou Rawash, Cairo Alexandria Desert Road, After Dandy Mall to the right. 23/ COCA COLA (Pivate) Abou El Ghyet, Al kanatr Al Khayreya Road, Kaliuob Alexandria ATM Address 1/ PHARCO PHARM 1 Alexandria Cairo Desert Road, Pharco Pharmaceutical Company 2/ CARREFOUR ALEXANDRIA City Center- Alexandria 3/ SAN STEFANO MALL El Amria, Alexandria 4/ ALEXANDRIA PORT Alexandria 5/ DEKHILA PORT El Dekhila, Alexandria 6/ ABOU QUIER FERTLIZER Eltabia, Rasheed Line, Alexandria 7/ PIRELLI CO. -

Cairo Traffic Congestion Study Phase 1

Cairo Traffic Congestion Study Phase 1 Final Report November 2010 This report was prepared by ECORYS Nederland BV and SETS Lebanon for the World Bank and the Government of Egypt, with funding provided by the Dutch - Egypt Public Expenditure Review Trust Fund. The project was managed by a World Bank team including Messrs. Ziad Nakat, Transport Specialist and Team Leader, and Santiago Herrera, Lead Country Economist. i Table of Content Executive Summary xi Study motivation xi Study area xi Data collection xi Observed Modal Split xii Identification of Causes, Types and Locations of Traffic Congestion xii Estimation of Direct Economic Costs of Traffic Congestion in Cairo xiv 1 Introduction 17 1.1 Background 17 1.2 Objective of the Study 18 1.3 Structure of this report 18 2 Assessment of Information Needs and Collection of Additional Data 19 2.1 Introduction 19 2.2 Task Description/Objectives 22 2.3 Study area 22 2.4 Assessment of Data and Information Needs 24 2.5 Floating Car Survey and Traffic Counts 25 2.5.1 Data Collection Objectives 25 2.5.2 Data Collection Techniques 25 2.5.3 Technical Plan Development Methodology 25 2.5.4 Development of Data Collection Technical Plan 29 2.5.5 Data Collection Operational Plan 32 2.6 Peak Hours 35 2.7 Traffic Composition in the Corridors 36 2.8 Modal Split in the Corridors 36 2.9 Daily Traffic Volume 45 2.10 Traffic Survey Results 49 2.11 Trend Analysis of Travel Characteristics (2005-2010) 62 2.11.1 Changes in Modal Split 62 2.11.2 Changes in Traffic Patterns 66 2.11.3 Changes in Peak Hours 71 2.12 Overview -

5.3 FUTURE ROAD SYSTEM PLANNING 5.3.1 Issues

CREATS Phase I Final Report Vol. III: Transport Master Plan Chapter 5: URBAN ROAD SYSTEM 5.3 FUTURE ROAD SYSTEM PLANNING 5.3.1 Issues (1) Regional Highway Network The Completion and Extension of the Ring Road Network At the end of July 2002, the Ring Road is basically complete except for the closing of the ring in southwest Giza. It has been a major struggle for the MHUUC how to close the Ring Road since its early days of construction. The alignment of the Ring Road in the southwest link shows that it has been critically difficult to close the link at the Haram area. The MHUUC was planning to extend the Ring Road from Interchange IC22 (see Figure 5.3.1) to the 6th of October Road, however, it was finally cancelled due to the international pressure for protecting the cultural heritage preservation area. The Ministry is now planning to extend the road from IC01 to the 6th of October Road by the plan shown in Figure 5.3.1. It also has a branch link to westward to bypass the traffic from the Ring Road (IC01) to Alexandria Desert Road. Source: JICA Study Team based on the information from GOPP Figure 5.3.1 The Ring Road Extension Plans One of the major functions of the Ring Road, to facilitate the connection to the 6th of October City with the existing urban area, can be achieved with this extension. However, unclosed Ring Road will still remain a problem in the network since 5 - 21 CREATS Phase I Final Report Vol. -

Cairo Traffic Congestion Study Executive Note May 2014

CAIRO TRAFFIC CONGESTION STUDY EXECUTIVE NOTE MAY 2014 The World Bank Group The World Bank Group Acknowledgments This study was undertaken by a World Bank team led by Ziad Nakat (Transport Specialist) and including Santiago Herrera (Lead Economist) and Yassine Cherkaoui (Infrastructure Specialist), and it was executed by Ecorys in collaboration with Sets and Cambridge Systematics. Funding for the study was generously provided by the Government of Netherlands; the Multi Donor Trust Fund “Addressing Climate Change in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region” supported by Italy’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the European Commission; the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program and the World Bank. 1 Cairo Traffic Congestion Study I Executive Note I. Introduction The Greater Cairo Metropolitan Area (GCMA), with more than 19 million inhabitants, is host to more than one-fifth of Egypt’s population. The GCMA is also an important contributor to the Egyptian economy in terms of GDP and jobs. The population of the GCMA is expected to further increase to 24 million by 2027, and correspondingly its importance to the economy will also increase. Traffic congestion is a serious problem in the GCMA with large and adverse effects on both the quality of life and the economy. In addition to the time wasted standing still in traffic, time that could be put to more productive uses, congestion results in unnecessary fuel consumption, causes additional wear and tear on vehicles, increases harmful emissions lowering air quality, increases the costs of transport for business, and makes the GCMA an unattractive location for businesses and industry. -

Fragmenting a Metropolis Sustainable Suburban Communities from Resettlement Ghettoes to Gated Utopias

OPEN ACCESS http://www.sciforum.net/conference/wsf3 Article Fragmenting a Metropolis Sustainable Suburban Communities from Resettlement Ghettoes to Gated Utopias Wael Salah Fahmi1,* 1 Department of Architecture, University of Helwan, 34, Abdel Hamid Lofti Street, Giza, 12311, Egypt; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +2 02 33370485 ; Fax: + 2- 02- 3335 1630 Received: 23 September 2013 / Accepted: 28 October 2013 / Published: 01 November 2013 Abstract: The paper examines the impact of the Greater Cairo Master Plan and New Towns Policy on urban housing crisis through some case studies focusing especially on New Cairo City, to the east of downtown Cairo. The empirical research attempts to qualitatively examine the complex reasons for the failure of various policies and implementations in meeting housing needs of middle and low-income people. This has resulted in the emergence of nearly empty new towns, and the increasing fortification of the affluent nouveaux riche within exclusive desert condominiums and gated communities, a phenomenon which aggravated social injustice and housing inequality. These communities’ global architectural styles and marketing strategies are linked to neo-liberal economic policies and private entrepreneurial urban governance related to individualised rights of seclusion, privacy and consumption. Influenced by expatriates in the Gulf monarchies, these desert enclaves are located in Greater Cairo's western desert (6th October City: Dream Land, Gardenia and Beverly Hills) and in the eastern suburbs (New Cairo City: Katameya Heights, Golf City, Al Rehab City, Mirage City, Arabella). Surrounded by golf courses, recreational and commercial facilities, these luxurious residential districts tend to be exterritorial with their construction, maintenance and economies, being largely controlled by international property development firms, whilst locally underlining the ever- sharper social disparity between rich and poor. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Name: Hossam Eldin M. A. Abouserie, PhD. Rank: Associate Professor of Library & Information Sciences. Current Position: Associate Professor, Library and Information Science Department, Faculty of Arts, Helwan University, Cairo, Egypt Previous Administrative Positions: Head of Libraries, Community College of Qatar, Doha, Qatar. University Library Supervisor, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Date of Birth: March, 10, 1974 Emails: [email protected] [email protected] Mobile: 00201004954917 & 002/23959674 Profile Dr. Hossam is an Associate Professor of Library and Information Science. He obtained five academic degrees in Library and Information Sciences fields from The United States of America and Egypt. He has a long experience in directing and supervising Academic libraries in Saudi Arabia and Qatar, as he was the university library supervisor in Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University for 7 years and Library Director in Community College of Qatar (January 2016- 2017). He has over 20 years of experience in teaching, research and service at several academic institutions in various countries, such as Egypt, United States of America, Qatar, and Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. He received several honor certifications from various academic institutions in various occasions. Dr. Hossam has a wide range of Interests from basic theories to the practice of implementing technologies in action. Beside teaching main courses in Library & Information Science, he gives special considerations to the following topics: Library Administration and Supervision, Library Management System (Symphony and Sierra - Innovative), Advertising and marketing, Information seeking, Knowledge theories, Information laws, Communication behaviors, E-learning, Information technology, Web designing, Web 2.0, Digital media, Telecommunication, Electronic journals, Electronic publishing, Scholarly communication, Culture and Society, Personality types, Research ethics, Research methods, Social networks, Arabic heritage and sources, etc. -

Ain Al-Sira Site Analysis

2013 Ehsan AbushadiEhsan Sira Site Analysis - Ain al Site Analysis of Ain al-Sira, for the design of a sustainable school for AENG 453. The site analysis looks at the history of the area, the topography, the water bodies and the situation today. The American University in Cairo Ehsan Abushadi 900092053 Aeng 453 A b u s h a d i P a g e | 2 Contents Table of Figures ........................................................................................... 3 Social Aspects .................................................................................... 27 Ain al-Sira General Overview ...................................................................... 5 Plot #3 ................................................................................................... 28 North Fustat and the Fustat Plateau ....................................................... 5 Physical Response ............................................................................. 28 Ain al-Sira, the Lake................................................................................. 5 Environmental Aspects ..................................................................... 28 Babylon (Qasr al-Sham)......................................................................... 11 Social Aspects .................................................................................... 28 Fustat, the city ...................................................................................... 11 Plot #4 .................................................................................................. -

Chapter 5 Outline Design (Phase 2)

CHAPTER 5 OUTLINE DESIGN (PHASE 2) JICA PREPARATORY SURVEY ON GREATER CAIRO METRO LINE NO. 4 CHAPTER 5 OUTLINE DESIGN (PHASE 2) The study of the Phase 2 Northern Route section between El Malek El Saleh and Ring Road Exit #18 via El Sawaha Square along Port Said Street was carried out at the level of an outline design. The train operating plan and required rolling stock number for the Phase 2 section was presented in Chapter 4, Section 4.2. Basic design concepts/criteria for Metro Line 4 Phase 2 are the same as for the Phase 1 section. These are presented in Chapter 4, Section 4.4. 5.1 Alignment Plan According to the result of route selection, the JICA Study Team considers an alignment and station location for the northern route. 5.1.1 Design criteria (1) Outline of Proposed Design Specifications Table 5-1 Key Features for Alignment Planning (Phase 2) Items Proposed Specification 1 Design speed Tunnel section: 100 km/hr Viaduct and At-grade section: 120 km/hr 2 Minimum horizontal Main line: 250 m curve radius Main line turnout curve: 160 m Workshop/Depot line: 160 m W/D line turnout curve: 120 m Platform section: 1000 m 3 Minimum vertical Over 600 m horizontal radius 3,000 m curve radius Less than 600 m horizontal radius 4,000 m 4 Maximum gradient Main line: 4% Platform section: 0.2% Stabling line: 0.2% Turnout section: 0% 5 Platform length Total: 170 m Source: JICA Study Team All the design criteria are same as in Phase 1. -

Egypt's Mega Projects

MEGAPROJECTS IN EGYPT FLANDERS INVESTMENT & TRADE MARKET SURVEY Market Study /////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// EGYPT’S MEGA PROJECTS 1.12.2018 //////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// www.flandersinvestmentandtrade.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Construction Projects ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 The New Administrative Capital 4 1.2 Al Galala City and Tourist Compound 5 1.3 Development of 10th of Ramadan City 6 1.4 The Northwest Coast Development Project 6 1.5 Damietta Furniture City 7 1.6 The Golden Triangle 7 1.7 The Grand Egyptian Museum 8 2. National power projects ........................................................................................................................................................ 9 2.1 El Dabaa Nuclear Power Plant 9 2.2 Jabal al-Zeit Wind Station 9 2.3 El Burullus Power Plant 10 2.4 Benban 1 Solar Plant 10 2.5 Beni Suef Combined Cycle Power Plant 11 2.6 New Capital Power Plant 11 2.7 New Assiut Barrage 12 2.8 Coal-Fired Power -

Accessibility Impact Analysis of New Public Transit Projects in Cairo, Egypt

Accessibility Impact Analysis of New Public Transit Projects in Cairo, Egypt By Adham Kalila B.Eng in Civil Engineering McGill University Montreal, Canada (2012) Master of Science in Transportation Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts (2018) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Urban Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2019 © 2019 Adham Kalila. All Rights Reserved The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author________________________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning 05/21/2019 Certified by____________________________________________________________________ Professor Sarah Williams Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by___________________________________________________________________ Professor of the Practice, Caesar McDowell Co-Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning Accessibility Impact Analysis of New Public Transit Projects in Cairo, Egypt By Adham Kalila Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 21, 2019 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Urban Planning Abstract The New Urban Communities (NUC), built around Cairo, developed to relieve congestion -

Chapter 4 Urban Transportation Plan

THE STRATEGIC URBAN DEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREATER CAIRO REGION IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT Final Report (Volume 2) CHAPTER 4 URBAN TRANSPORTATION PLAN 4.1 General Conditions of Urban Transportation 4.1.1 Existing Transportation Facilities (1) Railway 1) Metro The present urban railway network and urban railway transport services in the Greater Cairo area is shown in Figure 4.1.1 and Figure 4.1.2, respectively. The routes of Metro Line 1 and Metro Line 2 are also shown in Figure 4.1.1 and Figure 4.1.2. The location of the Metro Line 1 and Metro Line 2 stations is shown in Figure 4.1.1. Source: Edited based on Egyptian National Railways (hereafter ENR in this Chapter) data Figure 4.1.1 Urban Railway Network General Organization for Physical Planning Japan International Cooperation Agency Greater Cairo Region Urban Planning Center Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. Katahira & Engineers International 4-1 THE STRATEGIC URBAN DEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREATER CAIRO REGION IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT Final Report (Volume 2) Source: JICA Study Team, based on ENR data. Landsat image courtesy of USGS. Figure 4.1.2 Urban Railway Transport Service According to the recent data submitted by the Cairo Metro Organization (CMO) (hereafter referred to as CMO in this Chapter), as shown in Table 4.1.1, the average number of passengers per day between 05:15-24:15 amounted to 1.217 million on Metro Line 1 and 0.73 million on Metro Line 2 in 2005/2006. -

Road Safety Challenges in Egypt: a Discussion of Policy Alternatives

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2019 Road Safety Challenges in Egypt: A Discussion of Policy Alternatives Yasmine ElMoghazi Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation ElMoghazi, Y. (2019).Road Safety Challenges in Egypt: A Discussion of Policy Alternatives [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/790 MLA Citation ElMoghazi, Yasmine. Road Safety Challenges in Egypt: A Discussion of Policy Alternatives. 2019. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/790 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy Road Safety Challenges in Egypt: A Discussion of Policy Alternatives A Thesis Submitted to the Public Policy and Administration Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Policy By YASMINE ELMOGHAZI Spring 2019 The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy Department of Public Policy and Administration Road Safety Challenges in Egypt: A Discussion of Policy Alternatives By: YASMINE ELMOGHAZI, B.Sc. Supervised by: Dr. GHADA BARSOUM Associate Professor, The Public Policy and Administration Department ABSTRACT Road traffic injuries are a growing health epidemic with fatalities and injuries marking damaging emotional, social, and economic impacts on humans, countries and the world.