Preface to the Paperback Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egypt Real Estate Trends 2018 in Collaboration With

know more.. Egypt Real Estate Trends 2018 In collaboration with -PB- -1- -2- -1- Know more.. Continuing on the momentum of our brand’s focus on knowledge sharing, this year we lay on your hands the most comprehensive and impactful set of data ever released in Egypt’s real estate industry. We aspire to help our clients take key investment decisions with actionable, granular, and relevant data points. The biggest challenge that faces Real Estate companies and consumers in Egypt is the lack of credible market information. Most buyers rely on anecdotal information from friends or family, and many companies launch projects without investing enough time in understanding consumer needs and the shifting demand trends. Know more.. is our brand essence. We are here to help companies and consumers gain more confidence in every real estate decision they take. -2- -1- -2- -3- Research Methodology This report is based exclusively on our primary research and our proprietary data sources. All of our research activities are quantitative and electronic. Aqarmap mainly monitors and tracks 3 types of data trends: • Demographic & Socioeconomic Consumer Trends 1 Million consumers use Aqarmap every month, and to use our service they must register their information in our database. As the consumers progress in the usage of the portal, we ask them bite-sized questions to collect demographic and socioeconomic information gradually. We also send seasonal surveys to the users to learn more about their insights on different topics and we link their responses to their profiles. Finally, we combine the users’ profiles on Aqarmap with their profiles on Facebook to build the most holistic consumer profile that exists in the market to date. -

Reserve Great Apartment in New Heliopolis Near El Shorouk City

Reserve great apartment in new Heliopolis near el shorouk city Reference: 21037 Property Type: Apartments Property For: Sale Price: 675,000 EGP Country: Egypt Region: Cairo City: New Heliopolis Property Address: New Heliopolis cairo Price: 675,000 EGP Completion Date: 1970-01-01 Surface Area: 135 Unit Type: Flat Floor No: 03 No of Bedrooms: 2 No of Bathrooms: 1 Flooring: Cement Facing: North View: landscabe view Maintenance Fees: 5 % Deposit Union landlords Year Built: 2018 Real Estate License: residential Ownership Type: Registered Description: [tag]New Heliopolis[/tag] The total area of the city is 5888 acres made up of comprehensive residential places, services, recreational, educational, commercial, administrative, medical, social clubs, green open areas and the Golf. The Heliopolis Company for Development and housing was and is still the godfather of the city, providing all the facilities and services for the residents of the city including: Internal map of the city * Security gates * Integrated electricity network * Educational areas (schools- Institutes - Universities) The city is connected by the Cairo-Ismailia road from the north and by the CairoSuez road from the south. It also borders Madinaty to the south, El Shorouk to the west and Badr to the east. The city benefits from its connection to the Regional Ring Road which links it to all of Greater Cairo. The city is located 25 minutes from the district of Heliopolis and Nasr City Features: Elevator Balcony + View Master Bedroom Garage Close to the city Terrace Near Transport Luxury building Residential Area Quiet Area Shopping nearby Security Services . -

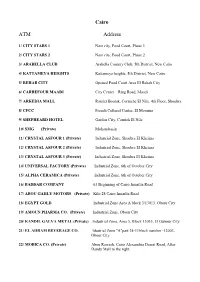

Cairo ATM Address

Cairo ATM Address 1/ CITY STARS 1 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 1 2/ CITY STARS 2 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 2 3/ ARABELLA CLUB Arabella Country Club, 5th District, New Cairo 4/ KATTAMEYA HEIGHTS Kattameya heights, 5th District, New Cairo 5/ REHAB CITY Opened Food Court Area El Rehab City 6/ CARREFOUR MAADI City Center – Ring Road, Maadi 7/ ARKEDIA MALL Ramlet Boulak, Corniche El Nile, 4th Floor, Shoubra 8/ CFCC French Cultural Center, El Mounira 9/ SHEPHEARD HOTEL Garden City, Cornish El Nile 10/ SMG (Private) Mohandessin 11/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 1 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 12/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 2 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 13/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 3 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 14/ UNIVERSAL FACTORY (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 15/ ALPHA CERAMICA (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 16/ BADDAR COMPANY 63 Beginning of Cairo Ismailia Road 17/ ABOU GAHLY MOTORS (Private) Kilo 28 Cairo Ismailia Road 18/ EGYPT GOLD Industrial Zone Area A block 3/13013, Obour City 19/ AMOUN PHARMA CO. (Private) Industrial Zone, Obour City 20/ KANDIL GALVA METAL (Private) Industrial Zone, Area 5, Block 13035, El Oubour City 21/ EL AHRAM BEVERAGE CO. Idustrial Zone "A"part 24-11block number -12003, Obour City 22/ MOBICA CO. (Private) Abou Rawash, Cairo Alexandria Desert Road, After Dandy Mall to the right. 23/ COCA COLA (Pivate) Abou El Ghyet, Al kanatr Al Khayreya Road, Kaliuob Alexandria ATM Address 1/ PHARCO PHARM 1 Alexandria Cairo Desert Road, Pharco Pharmaceutical Company 2/ CARREFOUR ALEXANDRIA City Center- Alexandria 3/ SAN STEFANO MALL El Amria, Alexandria 4/ ALEXANDRIA PORT Alexandria 5/ DEKHILA PORT El Dekhila, Alexandria 6/ ABOU QUIER FERTLIZER Eltabia, Rasheed Line, Alexandria 7/ PIRELLI CO. -

Urban Transport in the Oic Megacities

Standing Committee for Economic and Commercial Cooperation of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (COMCEC) URBAN TRANSPORT IN THE OIC MEGACITIES COMCEC COORDINATION OFFICE October 2015 COMCEC COORDINATION OFFICE October 2015 This report has been commissioned by the COMCEC Coordination Office to WYG and Fimotions. Views and opinions expressed in the report are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the official views of the COMCEC Coordination Office or the Member States of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation. Excerpts from the report can be made as long as references are provided. All intellectual and industrial property rights for the report belong to the COMCEC Coordination Office. This report is for individual use and it shall not be used for commercial purposes. Except for purposes of individual use, this report shall not be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including printing, photocopying, CD recording, or by any physical or electronic reproduction system, or translated and provided to the access of any subscriber through electronic means for commercial purposes without the permission of the COMCEC Coordination Office. For further information please contact: COMCEC Coordination Office Necatibey Caddesi No:110/A 06100 Yücetepe Ankara/TURKEY Phone : 90 312 294 57 10 Fax : 90 312 294 57 77 Web :www.comcec.org Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. -

Public Spaces in Transition Under Socio-Political Changes in Cairo

Benha University Faculty of Engineering at Shoubra Department of Architecture Public Spaces in Transition Under Socio-Political Changes in Cairo A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Architectural Engineering (Urban Design) Submitted by Ahmed Sayed Abdel-Rasoul Ali Assistant lecturer, architectural department Faculty of Engineering at Shoubra, Benha University Cairo, Egypt March 2018 Benha University Faculty of Engineering at Shoubra Department of Architecture Public Spaces in Transition Under Socio-Political Changes in Cairo A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Architectural Engineering (Urban Design) Submitted by Ahmed Sayed Abdel-Rasoul Ali Assistant lecturer, architectural department Faculty of Engineering at Shoubra, Benha University Supervised by Prof. Sadek Ahmed Sadek Prof. M. Khairy Amin Professor of urban design, architectural dept. Emeritus Professor, architectural dept. Faculty of Engineering at Shoubra, Benha University Faculty of Engineering at Shoubra, Benha University Ass. Prof. Eslam Nazmy Soliman Associate professor, Architectural dept. Faculty of Engineering at Shoubra, Benha Universityn Cairo, Egypt March 2018 Benha University Faculty of Engineering at Shoubra Department of Architecture Public Spaces in Transition Under Socio-Political Changes in Cairo APPROVAL SHEET Examination Committee Prof. Dr. Shaban Taha Ibrahim (Internal examiner and rapporteur) Emeritus Professor, Department of Architecture, faculty of Engineering -

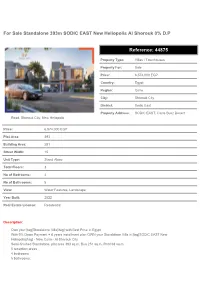

For Sale Standalone 393M SODIC EAST New Heliopolis Al Shorouk 0% D.P

For Sale Standalone 393m SODIC EAST New Heliopolis Al Shorouk 0% D.P Reference: 44875 Property Type: Villas / Townhouses Property For: Sale Price: 6,574,000 EGP Country: Egypt Region: Cairo City: Shorouk City District: Sodic East Property Address: SODIC EAST, Cairo-Suez Desert Road, Shorouk City, New Heliopolis Price: 6,574,000 EGP Plot Area: 393 Building Area: 251 Street Width: 15 Unit Type: Stand Alone Total Floors: 3 No of Bedrooms: 4 No of Bathrooms: 5 View: Water Features, Landscape Year Built: 2022 Real Estate License: Residential Description: Own your [tag]Standalone Villa[/tag] with Best Price in Egypt With 0% Down Payment + 8 years installment plan OWN your Standalone Villa in [tag]SODIC EAST New Heliopolis[/tag] - New Cairo - Al Shorouk City Semi-finished Standalone, plot area 393 sq.m, Bua 251 sq.m, Roof 68 sq.m 5 reception areas 4 bedrooms 5 bathrooms. Nanny room with private bathroom SODIC East will be a destination that offers a wide range of living solutions, with a close proximity to leisure, social, and edutainment nodes, collectively creating a truly integrated, walkable, modern community with a focus on innovation, efficiency, balance and connectivity. Strategically located between two of Cairos main throughways, The Cairo Suez Road and the Cairo Ismailia Road, SODIC East is directly adjacent to Al Sherouk City, and in close proximity to the new administrative Capital, as well as being easily connected to downtown Cairo, and just a few minutes drive from Cairos new regional ring road. SODIC East is committed to providing you with innovative housing solutions, ones that allow you to lead a smart, productive and creative life. -

Investgate April 2020

REAL ESTATE NEWS REPORTING & ANALYSIS APril 2020 - 44 PAGES - ISSUE 37 Developments SCAN TO DOWNLOAD THE DIGITAL VERSION 2 april 2020 - ISSUE 37 INVEST-GATE THE VOICE OF REAL ESTATE 3 4 april 2020 - ISSUE 37 INVEST-GATE THE VOICE OF REAL ESTATE 5 6 april 2020 - ISSUE 37 INVEST-GATE THE VOICE OF REAL ESTATE 7 A MESSAGE FROM INVEST-GATE Since Invest-Gate’s establishment, we made a commitment to the development of Egypt through its real estate investment industry. We have helped shape this new era by working closely with the government and the private sector to portray Egypt’s vision of urban development, breaking all barriers that might hinder its plan... a plan that would secure a better future for this generation and those to come. General Manager Invest-Gate has been the only successful platform, to which most- if not all - resort to when highlighting YASMINE EL NAHAS progress and addressing issues that obstruct their future. Invest-Gate has been the voice of you governmental Editor-in-Chief official, private investor, local broker, and homebuyer. FARAH MONTASSER At this time, we would have been celebrating our third anniversary. At this time, we would have been Contributing Editors highlighting many projects and guiding many homebuyers with their next investment. JULIAN NABIL At this time, we would have been traveling the world, representing Egypt as a safe investment hub, displaying YASMINE EL TAWDY all what this country has to offer from natural beauty, and a guaranteed return on investment. Business Reporters However, we stand today as part of the Egyptian community fighting the inevitable COVID-19, the global NOURAN MAHMOUD pandemic threat risking mankind. -

Cairo Traffic Congestion Study Phase 1

Cairo Traffic Congestion Study Phase 1 Final Report November 2010 This report was prepared by ECORYS Nederland BV and SETS Lebanon for the World Bank and the Government of Egypt, with funding provided by the Dutch - Egypt Public Expenditure Review Trust Fund. The project was managed by a World Bank team including Messrs. Ziad Nakat, Transport Specialist and Team Leader, and Santiago Herrera, Lead Country Economist. i Table of Content Executive Summary xi Study motivation xi Study area xi Data collection xi Observed Modal Split xii Identification of Causes, Types and Locations of Traffic Congestion xii Estimation of Direct Economic Costs of Traffic Congestion in Cairo xiv 1 Introduction 17 1.1 Background 17 1.2 Objective of the Study 18 1.3 Structure of this report 18 2 Assessment of Information Needs and Collection of Additional Data 19 2.1 Introduction 19 2.2 Task Description/Objectives 22 2.3 Study area 22 2.4 Assessment of Data and Information Needs 24 2.5 Floating Car Survey and Traffic Counts 25 2.5.1 Data Collection Objectives 25 2.5.2 Data Collection Techniques 25 2.5.3 Technical Plan Development Methodology 25 2.5.4 Development of Data Collection Technical Plan 29 2.5.5 Data Collection Operational Plan 32 2.6 Peak Hours 35 2.7 Traffic Composition in the Corridors 36 2.8 Modal Split in the Corridors 36 2.9 Daily Traffic Volume 45 2.10 Traffic Survey Results 49 2.11 Trend Analysis of Travel Characteristics (2005-2010) 62 2.11.1 Changes in Modal Split 62 2.11.2 Changes in Traffic Patterns 66 2.11.3 Changes in Peak Hours 71 2.12 Overview -

The Real Estate Industry and the Housing Crisis in Egypt

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AUC Knowledge Fountain (American Univ. in Cairo) American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2017 Between accumulation and (in)security: The real estate industry and the housing crisis in Egypt Norhan Sherif Mokhtar Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Mokhtar, N. (2017).Between accumulation and (in)security: The real estate industry and the housing crisis in Egypt [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1347 MLA Citation Mokhtar, Norhan Sherif. Between accumulation and (in)security: The real estate industry and the housing crisis in Egypt. 2017. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1347 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Studies Between Accumulation and (In)Security: The Real Estate Industry and the Housing Crisis in Egypt A Thesis Submitted to The Middle East Studies Center In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts By Norhan Sherif Mokhtar Hassan Under the supervision of Dr. Martina Rieker December 2017 © Copyright Norhan Sherif 2017 All Rights Reserved 1 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my parents for their patience and for putting up with me during the thesis and masters period that seemed almost everlasting. -

5.3 FUTURE ROAD SYSTEM PLANNING 5.3.1 Issues

CREATS Phase I Final Report Vol. III: Transport Master Plan Chapter 5: URBAN ROAD SYSTEM 5.3 FUTURE ROAD SYSTEM PLANNING 5.3.1 Issues (1) Regional Highway Network The Completion and Extension of the Ring Road Network At the end of July 2002, the Ring Road is basically complete except for the closing of the ring in southwest Giza. It has been a major struggle for the MHUUC how to close the Ring Road since its early days of construction. The alignment of the Ring Road in the southwest link shows that it has been critically difficult to close the link at the Haram area. The MHUUC was planning to extend the Ring Road from Interchange IC22 (see Figure 5.3.1) to the 6th of October Road, however, it was finally cancelled due to the international pressure for protecting the cultural heritage preservation area. The Ministry is now planning to extend the road from IC01 to the 6th of October Road by the plan shown in Figure 5.3.1. It also has a branch link to westward to bypass the traffic from the Ring Road (IC01) to Alexandria Desert Road. Source: JICA Study Team based on the information from GOPP Figure 5.3.1 The Ring Road Extension Plans One of the major functions of the Ring Road, to facilitate the connection to the 6th of October City with the existing urban area, can be achieved with this extension. However, unclosed Ring Road will still remain a problem in the network since 5 - 21 CREATS Phase I Final Report Vol. -

Cairo Traffic Congestion Study Executive Note May 2014

CAIRO TRAFFIC CONGESTION STUDY EXECUTIVE NOTE MAY 2014 The World Bank Group The World Bank Group Acknowledgments This study was undertaken by a World Bank team led by Ziad Nakat (Transport Specialist) and including Santiago Herrera (Lead Economist) and Yassine Cherkaoui (Infrastructure Specialist), and it was executed by Ecorys in collaboration with Sets and Cambridge Systematics. Funding for the study was generously provided by the Government of Netherlands; the Multi Donor Trust Fund “Addressing Climate Change in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region” supported by Italy’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the European Commission; the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program and the World Bank. 1 Cairo Traffic Congestion Study I Executive Note I. Introduction The Greater Cairo Metropolitan Area (GCMA), with more than 19 million inhabitants, is host to more than one-fifth of Egypt’s population. The GCMA is also an important contributor to the Egyptian economy in terms of GDP and jobs. The population of the GCMA is expected to further increase to 24 million by 2027, and correspondingly its importance to the economy will also increase. Traffic congestion is a serious problem in the GCMA with large and adverse effects on both the quality of life and the economy. In addition to the time wasted standing still in traffic, time that could be put to more productive uses, congestion results in unnecessary fuel consumption, causes additional wear and tear on vehicles, increases harmful emissions lowering air quality, increases the costs of transport for business, and makes the GCMA an unattractive location for businesses and industry. -

PROJECTS Q1 2017 SODIC Developments

PROJECTS Q1 2017 SODIC Developments NORTH COAST NEW HELIOPOLIS Cairo-Ismailia Road Cairo-Suez Road SHEIKH ZAYED NEW CAIRO CAIRO Cairo-Alexandria Desert Road Toll Station Road 90 AUC Dahshour Road Juhayna Square ESPLANADE 655 Acres WEST SODIC Developments NEW HELIOPOLIS Cairo-Ismailia Road Ring Road Cairo-Suez Road SHEIKH ZAYED Cairo International Airport NEW CAIRO Suez Road Heliopolis Cairo-Alexandria Desert Road River Nile Nasr City Toll Station Road 90 Mehwar Corridor Mohandeseen Downtown Cairo AUC Zamalek Dahshour Road Juhayna Square El Haram Waslet Maryoutia Ring Road Maadi Giza Pyramids Ain Sokhna Road ESPLANADE 655 Acres WEST WEST CAIRO PROJECTS Satellite Image 2017 2005 Designopolis SODIC Sales Centre Cairo-Alexandria Desert Road Westown Hub Westown Residences BISC Phase VII Westown Clubhouse The Polygon Allegria Westown Residences Phase V Westown Residences Westown Residences Phase IV Phase III Westown Courtyards Westown Westown Medical Centre Westown Residences Casa Phase VII Westown Residences Phase I ONE16 Westown Residences Forty West Phase II Belair Westown Residences Phase VI Dahshour Road Beverly Hills The Strip Sheikh Zayed City A Residential development situated in the heart of Westown offering diversified products. Cairo-Alexandria Desert Road Westown Hub The Pedestrian Green Spine No. of Launched Phases BISC The Pedestrian Green Spine runs through Westown 10 Residences, and acts as a gateway to the rest of Westown. Westown Clubhouse The Polygon Land Area (“000 sqm) 584 Westown Residences Total BUA (“000 sqm) Allegria The Courtyards 344 Construction Start Date SODIC Q1 2012 Headquarters Forty West Delivery Start Date Westown Residences Clubhouse CASA Q4 2013 Dahshour Road to Juhayna Square Total No.