Fragmenting a Metropolis Sustainable Suburban Communities from Resettlement Ghettoes to Gated Utopias

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egypt Real Estate Trends 2018 in Collaboration With

know more.. Egypt Real Estate Trends 2018 In collaboration with -PB- -1- -2- -1- Know more.. Continuing on the momentum of our brand’s focus on knowledge sharing, this year we lay on your hands the most comprehensive and impactful set of data ever released in Egypt’s real estate industry. We aspire to help our clients take key investment decisions with actionable, granular, and relevant data points. The biggest challenge that faces Real Estate companies and consumers in Egypt is the lack of credible market information. Most buyers rely on anecdotal information from friends or family, and many companies launch projects without investing enough time in understanding consumer needs and the shifting demand trends. Know more.. is our brand essence. We are here to help companies and consumers gain more confidence in every real estate decision they take. -2- -1- -2- -3- Research Methodology This report is based exclusively on our primary research and our proprietary data sources. All of our research activities are quantitative and electronic. Aqarmap mainly monitors and tracks 3 types of data trends: • Demographic & Socioeconomic Consumer Trends 1 Million consumers use Aqarmap every month, and to use our service they must register their information in our database. As the consumers progress in the usage of the portal, we ask them bite-sized questions to collect demographic and socioeconomic information gradually. We also send seasonal surveys to the users to learn more about their insights on different topics and we link their responses to their profiles. Finally, we combine the users’ profiles on Aqarmap with their profiles on Facebook to build the most holistic consumer profile that exists in the market to date. -

Effectiveness of Non-Pharmacological Nursing Intervention Program on Female Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis

Cent Eur J Nurs Midw 2017;8(3):682–690 doi: 10.15452/CEJNM.2017.08.0019 ORIGINAL PAPER EFFECTIVENESS OF NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL NURSING INTERVENTION PROGRAM ON FEMALE PATIENTS WITH RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS Eman Ali Metwaly1, Nadia Mohamed Taha1, Heba Abd El-Wahab Seliem2, Maha Desoky Sakr1 1Medical- Surgical Nursing Department, Faculty of Nursing, Zagazig University, Egypt 2Rheumatology and Rehabilitation Department, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt Received October 31, 2016; Accepted June 22, 2017. Copyright: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Aim: The aim of study was to evaluate the effectiveness of non-pharmacological nursing intervention programs on female patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Design: A quasi-experimental design was used in this study. Methods: Pre-post follow-up assessment of outcome was used in this study. The study was conducted in the inpatient and outpatient clinics of rheumatology and rehabilitation at Zagazig University Hospitals, Egypt. Results: There was a significant improvement in knowledge and practice of patients with RA in the post and follow-up phase of the program in the intervention group. In addition, the patients showed a high level of independence regarding ability to perform ADL. There was a statistically significant decrease in disability for patients in the intervention group. Conclusion: It is recommended that non-pharmacological intervention programs be implemented for patients with RA in different settings to help reduce the number of patients complaining of pain and disability. Keywords: intervention program, non-pharmacological, rheumatoid arthritis. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian Urban Exigencies: Space, Governance and Structures of Meaning in a Globalising Cairo A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Roberta Duffield Committee in charge: Professor Paul Amar, Chair Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse Assistant Professor Javiera Barandiarán Associate Professor Juan Campo June 2019 The thesis of Roberta Duffield is approved. ____________________________________________ Paul Amar, Committee Chair ____________________________________________ Jan Nederveen Pieterse ____________________________________________ Javiera Barandiarán ____________________________________________ Juan Campo June 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis committee at the University of California, Santa Barbara whose valuable direction, comments and advice informed this work: Professor Paul Amar, Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse, Professor Javiera Barandiarán and Professor Juan Campo, alongside the rest of the faculty and staff of UCSB’s Global Studies Department. Without their tireless work to promote the field of Global Studies and committed support for their students I would not have been able to complete this degree. I am also eternally grateful for the intellectual camaraderie and unending solidarity of my UCSB colleagues who helped me navigate Californian graduate school and come out the other side: Brett Aho, Amy Fallas, Tina Guirguis, Taylor Horton, Miguel Fuentes Carreño, Lena Köpell, Ashkon Molaei, Asutay Ozmen, Jonas Richter, Eugene Riordan, Luka Šterić, Heather Snay and Leila Zonouzi. I would especially also like to thank my friends in Cairo whose infinite humour, loyalty and love created the best dysfunctional family away from home I could ever ask for and encouraged me to enroll in graduate studies and complete this thesis: Miriam Afifiy, Eman El-Sherbiny, Felix Fallon, Peter Holslin, Emily Hudson, Raïs Jamodien and Thomas Pinney. -

Reserve Great Apartment in New Heliopolis Near El Shorouk City

Reserve great apartment in new Heliopolis near el shorouk city Reference: 21037 Property Type: Apartments Property For: Sale Price: 675,000 EGP Country: Egypt Region: Cairo City: New Heliopolis Property Address: New Heliopolis cairo Price: 675,000 EGP Completion Date: 1970-01-01 Surface Area: 135 Unit Type: Flat Floor No: 03 No of Bedrooms: 2 No of Bathrooms: 1 Flooring: Cement Facing: North View: landscabe view Maintenance Fees: 5 % Deposit Union landlords Year Built: 2018 Real Estate License: residential Ownership Type: Registered Description: [tag]New Heliopolis[/tag] The total area of the city is 5888 acres made up of comprehensive residential places, services, recreational, educational, commercial, administrative, medical, social clubs, green open areas and the Golf. The Heliopolis Company for Development and housing was and is still the godfather of the city, providing all the facilities and services for the residents of the city including: Internal map of the city * Security gates * Integrated electricity network * Educational areas (schools- Institutes - Universities) The city is connected by the Cairo-Ismailia road from the north and by the CairoSuez road from the south. It also borders Madinaty to the south, El Shorouk to the west and Badr to the east. The city benefits from its connection to the Regional Ring Road which links it to all of Greater Cairo. The city is located 25 minutes from the district of Heliopolis and Nasr City Features: Elevator Balcony + View Master Bedroom Garage Close to the city Terrace Near Transport Luxury building Residential Area Quiet Area Shopping nearby Security Services . -

Final Report on the Journey of 16 Women Candidates

Nazra For Feminist Studies 2 | Nazra for Feminist Studies Nazra for Feminist Studies is a group that aims to build an Egyptian feminist movement, believing that feminism and gender are political and social issues affecting freedom and development in all societies. Nazra aims to mai nstream these values in both public and private spheres. | About Women Political Participation Academy Nazra for Feminist Studies launched the Women Political Participation Academy in October 2011 based on its belief in the importance of women political participation and to contribute in activating women’s role in decision making on different political and social levels. The academy aims to support women’s role in their political participation and to build their capacity and support them in contesting in different elections like the people’s assembly, local councils & trade unions. For more information: http://nazra.org/en/programs/women -political-participation -academy- program | Contact Us [email protected] www.nazra.org | Team This report was written by Wafaa Osama, Advisor of the Women Political Participation Academy (WPPA). She was assisted in r esearch and documentation by Yehia Zayed, the Academy Trainer, and Was em Kamal, Statistical Analyst. Mohammad Sherin Atef, the Academy Consultant, Doaa Abdelaal, Mentoring on the Ground Consultant of the Academy, and Pense Al -Assiouty, Academy Coordinator, contributed to field- work. This report was edited by Mozn Hassan, the Executive Director of Nazra for Feminist Studies. This report was edited and translated into English by Elham Aydarous. | Copyright This report is published under a Creative Common s Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by -nc/3.0 | April 2013 Women Political Participation Academy Nazra For Feminist Studies April 2013 Nazra For Feminist Studies 3 Contents CHAPTER ONE: WOMEN IN PREVIOUS PARLIAMENTS .............................................................................. -

Mints – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY

No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 USD1.00 = EGP5.96 USD1.00 = JPY77.91 (Exchange rate of January 2012) MiNTS: Misr National Transport Study Technical Report 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Page CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 THE MINTS FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................1-1 1.2.1 Study Scope and Objectives .........................................................................................................1-1 -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

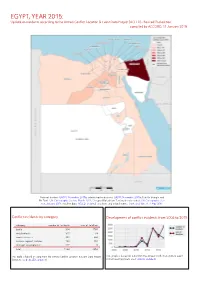

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

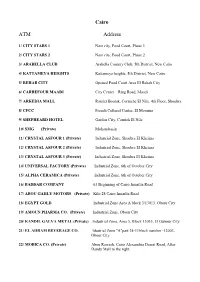

Cairo ATM Address

Cairo ATM Address 1/ CITY STARS 1 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 1 2/ CITY STARS 2 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 2 3/ ARABELLA CLUB Arabella Country Club, 5th District, New Cairo 4/ KATTAMEYA HEIGHTS Kattameya heights, 5th District, New Cairo 5/ REHAB CITY Opened Food Court Area El Rehab City 6/ CARREFOUR MAADI City Center – Ring Road, Maadi 7/ ARKEDIA MALL Ramlet Boulak, Corniche El Nile, 4th Floor, Shoubra 8/ CFCC French Cultural Center, El Mounira 9/ SHEPHEARD HOTEL Garden City, Cornish El Nile 10/ SMG (Private) Mohandessin 11/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 1 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 12/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 2 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 13/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 3 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 14/ UNIVERSAL FACTORY (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 15/ ALPHA CERAMICA (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 16/ BADDAR COMPANY 63 Beginning of Cairo Ismailia Road 17/ ABOU GAHLY MOTORS (Private) Kilo 28 Cairo Ismailia Road 18/ EGYPT GOLD Industrial Zone Area A block 3/13013, Obour City 19/ AMOUN PHARMA CO. (Private) Industrial Zone, Obour City 20/ KANDIL GALVA METAL (Private) Industrial Zone, Area 5, Block 13035, El Oubour City 21/ EL AHRAM BEVERAGE CO. Idustrial Zone "A"part 24-11block number -12003, Obour City 22/ MOBICA CO. (Private) Abou Rawash, Cairo Alexandria Desert Road, After Dandy Mall to the right. 23/ COCA COLA (Pivate) Abou El Ghyet, Al kanatr Al Khayreya Road, Kaliuob Alexandria ATM Address 1/ PHARCO PHARM 1 Alexandria Cairo Desert Road, Pharco Pharmaceutical Company 2/ CARREFOUR ALEXANDRIA City Center- Alexandria 3/ SAN STEFANO MALL El Amria, Alexandria 4/ ALEXANDRIA PORT Alexandria 5/ DEKHILA PORT El Dekhila, Alexandria 6/ ABOU QUIER FERTLIZER Eltabia, Rasheed Line, Alexandria 7/ PIRELLI CO. -

Trip to Egypt January 25 to February 8, 2020. Day 1

Address : Group72,building11,ap32, El Rehab city. Cairo ,Egypt. tel : 002 02 26929768 cell phone: 002 012 23 16 84 49 012 20 05 34 44 Website : www.mirusvoyages.com EMAIL:[email protected] Trip to Egypt January 25 to February 8, 2020. Day 1 Travel from Chicago to Cairo Day 2 Arrival at Cairo airport, meet & assistance, transfer to the hotel. Overnight at the hotel in Cairo. Day 3 Saqqara, the oldest complete stone building complex known in history, Saqqara features numerous pyramids, including the world-famous Step pyramid of Djoser, Visit the wonderful funerary complex of the King Zoser & Mastaba (Arabic word meaning 'bench') of a Noble. Lunch in a local restaurant. Visit the three Pyramids of Giza, the pyramid of Cheops is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and the only one to remain largely intact. ), the Great Pyramid was the tallest man-made structure in the world for more than 3,800 years. The temple of the valley & the Sphinx. Overnight at the hotel in Cairo. Day 4 Visit the Mokattam church, also known by Cave Church & garbage collectors( Zabbaleen) Mokattam, it is the largest church in the Middle East, seating capacity of 20,000. Visit the Coptic Cairo, Visit The Church of St. Sergius (Abu Sarga) is the oldest church in Egypt dating back to the 5th century A.D. The church owes its fame to having been constructed upon the crypt of the Holy Family where they stayed for three months, visit the Hanging Church (The Address : Group72,building11,ap32, El Rehab city. -

State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Geography Geography 2015 State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt Christine E. Smith University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Christine E., "State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt" (2015). Theses and Dissertations--Geography. 34. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/geography_etds/34 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Geography at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Geography by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Resistant Escherichia Coli: a Risk to Public Health and Food Safety

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Poultry hatcheries as potential reservoirs for antimicrobial- resistant Escherichia coli: A risk to Received: 12 September 2017 Accepted: 21 March 2018 public health and food safety Published: xx xx xxxx Kamelia M. Osman1, Anthony D. Kappell2, Mohamed Elhadidy3,4, Fatma ElMougy5, Wafaa A. Abd El-Ghany6, Ahmed Orabi1, Aymen S. Mubarak7, Turki M. Dawoud7, Hassan A. Hemeg8, Ihab M. I. Moussa7, Ashgan M. Hessain9 & Hend M. Y. Yousef10 Hatcheries have the power to spread antimicrobial resistant (AMR) pathogens through the poultry value chain because of their central position in the poultry production chain. Currently, no information is available about the presence of AMR Escherichia coli strains and the antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) they harbor within hatchezries. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the possible involvement of hatcheries in harboring hemolytic AMR E. coli. Serotyping of the 65 isolated hemolytic E. coli revealed 15 serotypes with the ability to produce moderate bioflms, and shared susceptibility to cephradine and fosfomycin and resistance to spectinomycin. The most common β-lactam resistance gene was blaTEM, followed by blaOXA-1, blaMOX-like, blaCIT-like, blaSHV and blaFOX. Hierarchical clustering of E. coli isolates based on their phenotypic and genotypic profles revealed separation of the majority of isolates from hatchlings and the hatchery environments, suggesting that hatchling and environmental isolates may have diferent origins. The high frequency of β-lactam resistance genes in AMR E. coli from chick hatchlings indicates that hatcheries may be a reservoir of AMR E. coli and can be a major contributor to the increased environmental burden of ARGs posing an eminent threat to poultry and human health. -

Maat for Peace, Development, and Human Rights

Violating Rights of Local Civilian Submitted to: Mechanism of Universal Periodical Review By: Maat for Peace, Development, and Human Rights. August 2009 انعنوان: أول ش انمهك فيصم - برج اﻷطباء – اندور انتاسع – شقه 908 – انجيزة ت / ف : 37759512 /02 35731912 /02 موبايم : 5327633 010 6521170 012 انبريد اﻻنكتروني : [email protected] [email protected] انموقع: www.maatpeace.org www.maat-law.org Report Methodology This report will discuss four components which are drinking water, draining services, environment services, and health services. The report will focus on those four components because there is a connection between them and because they are the more urgent and spread needs watched by Maat Institution. This report depended on three information sources: 1- Results of discussion meetings with citizens: there are 33 discussion meetings were held in some Egyptian governorates, in order to define problems and violations related to public utilities and essential services. 2- Citizens complaints: big number of citizens and their representatives in local public councils delivered written complaints to Maat Institution about specific violations they suffer regarding public utilities and essential services. 3- Journalism subjects published in Egyptian journals regarding violations of economical and social rights and depriving from essential services. First violation regarding the right to have safe drinking water: Egypt witnessed in the last three years increasing public anger because of shortage in drinking water available in many places of the republic. Thus, protest forms rose like demonstrations and stays-in strike to force executive managers to solve this problem. This period also witnessed many cases of water pollutions or mixing drinking water with draining water this is the problem which makes many people infected with hepatitis and renal failure.