Diplomarbeit FINAL!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Jan Van Pelt Auschwitz, Holocaust-Leugnung Und Der Irving-Prozess

ROBERT JAN VAN PELT AUSCHWITZ, HOLOCAUST-LEUGNUNG UND DER IRVING-PROZESS Robert Jan van Pelt Auschwitz, Holocaust-Leugnung und der Irving-Prozess In 1987 I decided to investigate the career and fate of the came an Ortsgeschichte of Auschwitz. This history, publis- architects who had designed Auschwitz. That year I had hed as Auschwitz: 1270 to the Present (1996), tried to re- obtained a teaching position at the School of Architecture create the historical context of the camp that had been of of the University of Waterloo in Canada. Considering the relevance to the men who created it. In 1939, at the end of question of the ethics of the architectural profession, I be- the Polish Campaign, the Polish town of Oswiecim had came interested in the worst crime committed by archi- been annexed to the German Reich, and a process of eth- tects. As I told my students, “one can’t take a profession nic cleansing began in the town and its surrounding coun- seriously that hasn’t insisted that the public authorities tryside that was justified through references to the medie- hang one of that profession’s practitioners for serious pro- val German Drang nach Osten. Also the large-scale and fessional misconduct.” I knew that physicians everywhere generally benign “Auschwitz Project,” which was to lead had welcomed the prosecution and conviction of the doc- to the construction of a large and beautiful model town of tors who had done medical experiments in Dachau and some 60,000 inhabitants supported by an immense synthe- other German concentration camps. -

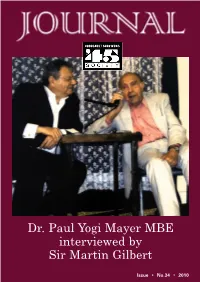

Dr. Paul Yogi Mayer MBE Interviewed by Sir Martin Gilbert

JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 1 Dr. Paul Yogi Mayer MBE interviewed by Sir Martin Gilbert Issue • No.34 • 2010 JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 2 CH ARTER ED AC C OU NTANTS MARTIN HELLER 5 North End Road • London NW11 7RJ Tel 020 8455 6789 • Fax 020 8455 2277 email: [email protected] REGISTERED AUDIT ORS simmons stein & co. SOLI CI TORS Compass House, Pynnacles Close, Stanmore, Middlesex HA7 4AF Telephone 020 8954 8080 Facsimile 020 8954 8900 dx 48904 stanmore web site www.simmons-stein.co.uk Gary Simmons and Jeffrey Stein wish the ’45 Aid every success 2 JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 3 THE ’45 AID SOCIETY (HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS) PRESIDENT SECRETARY SIR MARTIN GILBERT C.B.E.,D.LITT., F.R.S.L M ZWIREK 55 HATLEY AVENUE, BARKINGSIDE, VICE PRESIDENTS IFORD IG6 1EG BEN HELFGOTT M.B.E., D.UNIV. (SOUTHAMPTON) COMMITTEE MEMBERS LORD GREVILLE JANNER OF M BANDEL (WELFARE OFFICER), BRAUNSTONE Q.C. S FREIMAN, M FRIEDMAN, PAUL YOGI MAYER M.B.E. V GREENBERG, S IRVING, ALAN MONTEFIORE, FELLOW OF BALLIOL J KAGAN, B OBUCHOWSKI, COLLEGE, OXFORD H OLMER, I RUDZINSKI, H SPIRO, DAME SIMONE PRENDEGAST D.B.E., J.P., D.L. J GOLDBERGER, D PETERSON, KRULIK WILDER HARRY SPIRO SECRETARY (LONDON) MRS RUBY FRIEDMAN CHAIRMAN BEN HELFGOTT M.B.E., D.UNIV. SECRETARY (MANCHESTER) (SOUTHAMPTON) MRS H ELLIOT VICE CHAIRMAN ZIGI SHIPPER JOURNAL OF THE TREASURER K WILDER ‘45 AID SOCIETY FLAT 10 WATLING MANSIONS, EDITOR WATLING STREET, RADLETT, BEN HELFGOTT HERTS WD7 7NA All submissions for publication in the next issue (including letters to the Editor and Members’ News Items) should be sent to: RUBY FRIEDMAN, 4 BROADLANDS, HILLSIDE ROAD, RADLETT, HERTS WD7 7BX ACK NOW LE DG MEN TS SALEK BENEDICT for the cover design. -

Destruction and Human Remains

Destruction and human remains HUMAN REMAINS AND VIOLENCE Destruction and human remains Destruction and Destruction and human remains investigates a crucial question frequently neglected in academic debate in the fields of mass violence and human remains genocide studies: what is done to the bodies of the victims after they are killed? In the context of mass violence, death does not constitute Disposal and concealment in the end of the executors’ work. Their victims’ remains are often treated genocide and mass violence and manipulated in very specific ways, amounting in some cases to true social engineering with often remarkable ingenuity. To address these seldom-documented phenomena, this volume includes chapters based Edited by ÉLISABETH ANSTETT on extensive primary and archival research to explore why, how and by whom these acts have been committed through recent history. and JEAN-MARC DREYFUS The book opens this line of enquiry by investigating the ideological, technical and practical motivations for the varying practices pursued by the perpetrator, examining a diverse range of historical events from throughout the twentieth century and across the globe. These nine original chapters explore this demolition of the body through the use of often systemic, bureaucratic and industrial processes, whether by disposal, concealment, exhibition or complete bodily annihilation, to display the intentions and socio-political frameworks of governments, perpetrators and bystanders. A NST Never before has a single publication brought together the extensive amount of work devoted to the human body on the one hand and to E mass violence on the other, and until now the question of the body in TTand the context of mass violence has remained a largely unexplored area. -

The Holocaust As Public History

The University of California at San Diego HIEU 145 Course Number 646637 The Holocaust as Public History Winter, 2009 Professor Deborah Hertz HSS 6024 858 534 5501 Class meets 12---12:50 in Center 113 Please do not send me email messages. Best time to talk is right after class. It is fine to call my office during office hours. You may send a message to me on the Mail section of our WebCT. You may also get messages to me via Ms Dorothy Wagoner, Judaic Studies Program, 858 534 4551; [email protected]. Office Hours: Wednesdays 2-3 and Mondays 11-12 Holocaust Living History Workshop Project Manager: Ms Theresa Kuruc, Office in the Library: Library Resources Office, last cubicle on the right [turn right when you enter the Library] Phone: 534 7661 Email: [email protected] Office hours in her Library office: Tuesdays and Thursdays 11-12 and by appointment Ms Kuruc will hold a weekly two hour open house in the Library Electronic Classroom, just inside the entrance to the library to the left, on Wednesday evenings from 5-7. Students who plan to use the Visual History Archive for their projects should plan to work with her there if possible. If you are working with survivors or high school students, that is the time and place to work with them. Reader: Mr Matthew Valji, [email protected] WebCT The address on the web is: http://webct.ucsd.edu. Your UCSD e-mail address and password will help you gain entry. Call the Academic Computing Office at 4-4061 or 4-2113 if you experience problems. -

Holocaust Denial Cases and Freedom of Expression in the United States

Holocaust Denial Cases and Freedom of Expression in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom By Charla Marie Boley Submitted to Central European University, Department of Legal Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of … M.A. in Human Rights Supervisor: Professor Vladimir Petrovic Budapest, Hungary 2016 CEU eTD Collection Copyright 2016 Central European University CEU eTD Collection i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Freedom of expression is an internationally recognized fundamental right, crucial to open societies and democracy. Therefore, when the right is utilized to proliferate hate speech targeted at especially vulnerable groups of people, societies face the uncomfortable question of how and when to limit freedom of expression. Holocaust denial, as a form of hate speech, poses such a problem. This particular form of hate speech creates specific problems unique to its “field” in that perpetrators cloak their rhetoric under a screen of academia and that initial responses typically discard it as absurd, crazy, and not worth acknowledging. The three common law jurisdictions of the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom all value free speech and expression, but depending on national legislation and jurisprudence approach the question of Holocaust denial differently. The three trials of Holocaust deniers Zundel, Irving, and the the Institute for Historical Review, a pseudo academic organization, caught the public’s attention with a significant amount of sensationalism. The manner in which the cases unfolded and their aftermath demonstrate that Holocaust denial embodies anti-Semitism and is a form of hate speech. Furthermore, examination of trial transcripts, media response, and existing scholarship, shows that combating denial in courtrooms can have the unintended consequence of further radicalizing deniers and swaying more to join their ranks. -

A Genealogist Reveals the Painful Truth About Three Holocaust Memoirs: They’Re Fiction

discrepancies among names and dates in different translations helped to reveal the author’s true identity. A genealogist reveals the painful truth about three Holocaust memoirs: they’re fiction Untrue Stories BY cAleB dAniloff Detractors have called Sharon Sergeant a witch-hunter, a Holocaust denier, and even a Nazi. 32 BOSTONIA Summer 2009 PHOTograph by vernon doucette Summer 2009 BOSTONIA 33 In her 1997 autobiography, Misha: A Memoire The tools of her profession include photographic timelines and data- of the Holocaust Years, Belgian-born Misha bases — vital records, census reports, Defonseca claimed to have trekked war- property deeds, maps, newspaper interviews, obituaries, phone direc- pocked Europe for four years, starting at the tories — and living relatives. Skype, online records, and blogs have also age of seven, in search of her deported Jewish broadened her reach, and DNA testing parents. Along the way, she wrote, she took up is an option if she needs it. “The generic view of genealogy with a pack of wolves, slipped in and out of the is that it is about tracing relatives, the ‘begats,’” says Sergeant, a board Warsaw Ghetto, and killed a Nazi soldier. member and former programs director with the Massachusetts Genealogical In Europe, the book was a smash, court’s decision by proving the author Council. “It’s evolved.” translated into eighteen languages was a fraud. But her involvement in cracking and made into a hit film. In the It was there online, one day in open three Holocaust hoaxes is about United States, however, it had sold December 2007, that Sharon Sergeant more than an interest in the latest poorly — so poorly that Defonseca (MET’83), now an adjunct faculty technology. -

The Bunkers Auschwitz

z t CCarloarlo MMattognoattogno The so-called “Bunkers” at i Au schwitz-Birkenau are claimed w to have been the fi rst homicidal gas h chambers at Auschwitz specifically c s erected for this purpose in early 1942. u TThehe BBunkersunkers In this examination of a critical com- A ponent of the Auschwitz extermination f ooff legend, the indefatigable Carlo Mat- o togno has combed tens of thousands s of documents from the Auschwitz r AAuschwitzuschwitz construction offi ce – to conclude that these “Bunkers” e k never existed. n The Bunkers of Auschwitz shows how camp rumors u B of these alleged gas chambers evolved into black propa- ganda created by resistance groups within the camp, and e how this black propaganda was subsequently transformed h The Bunkers of Auschwitz TThe Bunkers of into “reality” by historians who uncritically embraced • everything stated by alleged eyewitnesses. o n In a concluding section that analyzes such hands-on g o t evidence as wartime aerial photography and archeologi- t cal diggings, Mattogno bolsters his case that the Aus- a M chwitz “bunkers” were – and remain – nothing more o than propaganda bunk. l r a CCarlo Mattogno • ISSN 1529–7748 BBlacklack PPropagandaropaganda vversusersus HHistoryistory ISBN 978-1–59148–009–4 ISBN 978-1-59148-009-490000> HHOLOCAUSTOLOCAUST HHandbooksandbooks SeriesSeries VVolumeolume 1111 TThesesheses & DissertationsDissertations PPressress PPOO BBoxox 225776857768 CChicago,hicago, IILL 660625,0625, UUSASA 9781591 480099 THE BUNKERS OF AUSCHWITZ BLACK PROPAGANDA VERSUS HISTORY The Bunkers of Auschwitz Black Propaganda versus History Carlo Mattogno Theses & Dissertations Press PO Box 257768, Chicago, Illinois 60625 December 2004 HOLOCAUST Handbooks Series, Vol. -

U S Er G U I D E I Nsi De T H E Nazi Stat E

INSIDE THE NAZI STATE EDUCATOR’S EDITION U S E R G U I D E C O N T E N T S 4. Introduction 4. Unique features of the series 6. A Scholar’s Perspective As the generation that by Robert Jan van Pelt 11. Getting started directly experienced the 11. Target audience Holocaust gets smaller and 11. Curriculum planning 12. Computer specifications the world becomes more 12. Installation instructions 12. Connecting your computer to an lcd complex and interconnected, 13. Finding what you want it becomes particularly 14. DVD interface 16. By episode critical to examine the 17. Index of video segments historical record and what it 18. By essential question 19. By unit tells us about power, politics, 20. By resource personal responsibility, 21. Printing from the disk violence, racism, prejudice, 22. Frequently asked questions 23. For further information and diversity. 25. Funders ) 25. Credits BBC (© 1939 Photo (left): Nazis occupying Poland, Poland, occupying Photo Nazis (left): 2 INTRODUCTION of meetings, testimony from people who were in the meetings, and memoirs from such individuals as camp commandant 27 1945 7,600 On January , , the Red Army liberated the survivors Rudolf Höss). All dramatizations were extensively reviewed by remaining at Auschwitz. Of the more than one million people project scholars for their accuracy. They were filmed in German who had been sent there in the previous four years, most had and have English captioning. been killed. At the time of the liberation, little was known about the COMPUTER RECONSTRUCTIONS site or about people’s experiences there. Since the fall of Com- 1990 munism in the former Soviet Union, significant primary sources During the s the entire set of building plans relating to have become available to scholars that reveal a detailed four-year Auschwitz at all of its various stages was uncovered in Russian 3-d history of this Nazi institution. -

Current to April 2017) Strassler Center for Holocaust Tel: (508

Dwork, April 2017 DEBÓRAH DWORK (current to April 2017) Strassler Center for Holocaust Tel: (508) 793-8897 and Genocide Studies Fax: (508) 793-8827 Clark University Email: [email protected] 950 Main Street Worcester, MA 01610-1477 EDUCATION 1984 Ph.D. University College, London 1978 M.P.H. Yale University 1975 B.A. Princeton University EMPLOYMENT 2016-present Founding Director Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies 1996-present Rose Professor of Holocaust History Professor of History Clark University 1996-2016 Director Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies Rose Professor of Holocaust History Professor of History Clark University 1991-1996 Associate Professor Child Study Center, Yale University 1989-1991 Visiting Assistant Professor Child Study Center, Yale University 1987-1989 Assistant Professor Department of Public Health Policy, School of Public Health University of Michigan 1984-1987 Visiting Assistant Professor Dept. of History, University of Michigan (1984-86) Dept. of Public Health Policy (1986-87) 1984 Post-Doctoral Fellow Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. - 1 - Dwork, April 2017 GRANTS AND AWARDS 2016-17 Grant, Anonymous Foundation (Clark University administered) 2015-17 Grant, Cathy Cohen Lasry (Clark University administered) 2009-11 Grant, Shillman Foundation 2007-08 Grant, Shillman Foundation 2003-05 Grant, Tapper Charitable Foundation 1993-96 Grant, Anonymous Donor (Yale University administered) 1994 Grant, New Land Foundation 1993-94 Fellow, Guggenheim Foundation 1992-94 Grant, Lustman Fund 6-8/1992 Grant, National Endowment for the Humanities 1991-1992 Grant, Lustman Fund 1-9/1989 Fellow, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars 1-6/1988 Fellow, American Council of Learned Societies 1988 Grant, Rackham Faculty Grant for Research (Univ. -

Fake Memory - Please Do Not Copy Or Cite Without Authors’ Permission

UJ Sociology, Anthropology & Development Studies W E D N E S D A Y S E M I N A R Hosted by the Department of Sociology and the Department of Anthropology & Development Studies Meeting no 10/2010 To be held at 15h30 on Wednesday, 31 March 2010, in the Anthropology & Development Studies Seminar Room, DRing 506, Kingsway campus Fake Memory - Please do not copy or cite without authors’ permission - Prof David William Cohen Director: International Institute, University of Michigan - Programme and other information online at www.uj.ac.za/sociology - 1 Fake Memory David William Cohen, 13 March 2010 At a precipice. Fake memory. To one side, a gorge filling with broken stories, historical fictions, counterfeit memoirs, inventions, frauds, discredited claims, fake memories. To the other side, finders of fact, debunkers, critics, historians, truth finders, vexed audiences. Where to stand? * * * It was for Oprah Winfrey one of the greatest love stories ever told. Every day, for months, a young girl sends apples over a fence at Buchenwald to a boy, an inmate of the concentration camp. Almost 15 years later, Herman was living and working in New York City. A friend set him up on a blind date with a woman named Roma Radzika. Herman says he was immediately drawn to her. When they began talking about their lives, Roma asked Herman where he was during World War II. "I said, 'In a concentration camp,'" he says. "And then she says, 'I came to a camp and I met a boy there and I gave him some apples and I sent them over the fence.' "And suddenly it hit me like a ton of bricks. -

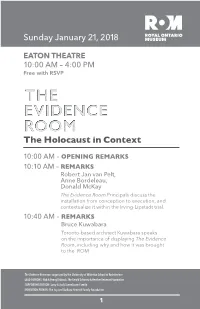

The Holocaust in Context

Sunday January 21, 2018 EATON THEATRE 10:00 AM – 4:00 PM Free with RSVP The Holocaust in Context 10:00 AM – OPENING REMARKS 10:10 AM – REMARKS Robert Jan van Pelt, Anne Bordeleau, Donald McKay The Evidence Room Principals discuss the installation from conception to execution, and contextualize it within the Irving-Lipstadt trial. 10:40 AM – REMARKS Bruce Kuwabara Toronto-based architect Kuwabara speaks on the importance of displaying The Evidence Room, including why and how it was brought to the ROM. The Evidence Room was organized by the University of Waterloo School of Architecture LEAD PATRONS: Rob & Penny Richards, The Gerald Schwartz & Heather Reisman Foundation SUPPORTING PATRON: Larry & Judy Tanenbaum Family EXHIBITION PATRON: The Jay and Barbara Hennick Family Foundation 1 Sunday January 21, 2018 EATON THEATRE 10:00 AM – 4:00 PM Free with RSVP 11:00 AM – TOWERS OF DEATH AND LIFE: ARCHITECTURE AND MEANING AT THE 2016 VENICE BIENNALE John Onians The reconstructed tower for the administration of deadly gas to the innocent victims of Nazi persecution, the centrepiece of The Evidence Room, was by far the most sinister object at the Venice Biennale. Indeed it is perhaps the most sinister object to have been produced since the War. At the Biennale it was not, however, deprived of its aura of hope. This was activated most directly by its formal resemblance to Arturo Vettori’s neighbouring Dwarka tower, designed to capture life-saving water from the air for the benefit of some of the poorest inhabitants of our earth. More paradoxically it was also evoked by the careful attention to detail manifested by the Canadian team responsible for its conception and realisation. -

By Alyson Miller, Bachelor of Arts

SCANDALOUS TEXTS: THE ANXIETIES OF THE LITERARY By Alyson Miller, Bachelor of Arts (Hons.) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Deakin University September 2010 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY CANDIDATE DECLARATION I certify that the thesis entitled Scandalous Texts: The Anxieties of the Literary submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy is the result of my own work and that where reference is made to the work of others, due acknowledgment is given. I also certify that any material in the thesis which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by any university or institution is identified in the text. Full Name: Alyson Miller Signed…………………………………………… Date: September 6, 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Dr Maria Takolander and Dr David McCooey: for a beginning, a middle and the end of many green pens. Mum and Dad: for the patient belief, the coffee, the clean washing, and ‘the’, ‘and’, ‘a’, ‘at’ and ‘with’. James and Lisa: for pumpkins and boats, waffles and Mexico. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Scandalous Texts: Haunted by Words 1 CHAPTER ONE Unsuited to Age Group: The Anxieties of Children’s Literature 9 Framing the Child: Childhood, Children and Literature Igniting Debate: The Scandalous Texts ‘Feel Yer Tits?’: Sexual Content in Young Adult Literature A Scandalous Absence: Controversy and Race Masterpieces of Satanic Deception: Transgressing the Sacred An Anxious Connection: Children and Literature CHAPTER TWO Dismembering Women: Gender and Identity in Top-Notch Smut 39 Femmes Fatales: Madame Bovary, The Well