By Alyson Miller, Bachelor of Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Modernity?: the Modernist, Postmodernist, and Para-Modernist

WHAT IS MODERNITY?: THE MODERNIST, POSTMODERNIST, AND PARA-MODERNIST WORLDS IN THE FICTION OF MURAKAMI HARUKI by MICHAEL FRANKLIN WARD (Under the Direction of Carolyn Jones Medine) ABSTRACT The following thesis is the culmination of three years of studying the fiction of the Japanese writer Murakami Haruki (1949- ) and various theories of modernism, postmodernism, and paramodernism of both Japanese and Western origin. In this thesis I map out both prewar and postwar Japanese modernism and how Murakami fits or does not fit into their parameters, map out how Murakami creates his own personal history in postmodern Japan, and how he acts as a paramodernist “filter” between East and West. INDEX WORDS: Japanese prewar modernism, Japanese postwar modernism, Murakami Haruki, Postmodernism, and Paramodernism WHAT IS MODERNITY?: THE MODERNIST, POSTMODERNIST, AND PARAMODERNIST WORLDS IN THE FICTION OF MURAKAMI HARUKI by MICHAEL FRANKLIN WARD B.A., University of Georgia, 2001 M.A., University of Kansas, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Michael Franklin Ward All Rights Reserved WHAT IS MODERNITY?: THE MODERNIST, POSTMODERNIST, AND PARAMODERNIST WORLDS IN THE FICTION OF MURAKAMI HARUKI by MICHAEL FRANKLIN WARD Major Professor: Carolyn Jones Medine Committee: Sandy D. Martin Hyangsoon Yi Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2009 iv DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my beloved fiancé Kuriko Sakurai whose love and support has helped me through the past three years and whose wit, intelligence, and humor stimulated not only my desire to produce a good academic work but has also increased my love for her each day. -

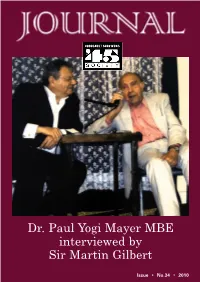

Dr. Paul Yogi Mayer MBE Interviewed by Sir Martin Gilbert

JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 1 Dr. Paul Yogi Mayer MBE interviewed by Sir Martin Gilbert Issue • No.34 • 2010 JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 2 CH ARTER ED AC C OU NTANTS MARTIN HELLER 5 North End Road • London NW11 7RJ Tel 020 8455 6789 • Fax 020 8455 2277 email: [email protected] REGISTERED AUDIT ORS simmons stein & co. SOLI CI TORS Compass House, Pynnacles Close, Stanmore, Middlesex HA7 4AF Telephone 020 8954 8080 Facsimile 020 8954 8900 dx 48904 stanmore web site www.simmons-stein.co.uk Gary Simmons and Jeffrey Stein wish the ’45 Aid every success 2 JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 3 THE ’45 AID SOCIETY (HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS) PRESIDENT SECRETARY SIR MARTIN GILBERT C.B.E.,D.LITT., F.R.S.L M ZWIREK 55 HATLEY AVENUE, BARKINGSIDE, VICE PRESIDENTS IFORD IG6 1EG BEN HELFGOTT M.B.E., D.UNIV. (SOUTHAMPTON) COMMITTEE MEMBERS LORD GREVILLE JANNER OF M BANDEL (WELFARE OFFICER), BRAUNSTONE Q.C. S FREIMAN, M FRIEDMAN, PAUL YOGI MAYER M.B.E. V GREENBERG, S IRVING, ALAN MONTEFIORE, FELLOW OF BALLIOL J KAGAN, B OBUCHOWSKI, COLLEGE, OXFORD H OLMER, I RUDZINSKI, H SPIRO, DAME SIMONE PRENDEGAST D.B.E., J.P., D.L. J GOLDBERGER, D PETERSON, KRULIK WILDER HARRY SPIRO SECRETARY (LONDON) MRS RUBY FRIEDMAN CHAIRMAN BEN HELFGOTT M.B.E., D.UNIV. SECRETARY (MANCHESTER) (SOUTHAMPTON) MRS H ELLIOT VICE CHAIRMAN ZIGI SHIPPER JOURNAL OF THE TREASURER K WILDER ‘45 AID SOCIETY FLAT 10 WATLING MANSIONS, EDITOR WATLING STREET, RADLETT, BEN HELFGOTT HERTS WD7 7NA All submissions for publication in the next issue (including letters to the Editor and Members’ News Items) should be sent to: RUBY FRIEDMAN, 4 BROADLANDS, HILLSIDE ROAD, RADLETT, HERTS WD7 7BX ACK NOW LE DG MEN TS SALEK BENEDICT for the cover design. -

Move Then Skin Deep

More than Skin Deep: Masochism in Japanese Women’s Writing 1960-2005 by Emerald Louise King School of Asian Languages and Studies Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Arts) University of Tasmania, November 2012 Declaration of Originality “This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and dully acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgment is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright.” Sections of this thesis have been presented at the 2008 Australian National University Asia Pacific Week in Canberra, the 2008 University of Queensland Rhizomes Conference in Queensland, the 2008 Asian Studies Association of Australia Conference in Melbourne, the 2008 Women in Asia Conference in Queensland, the 2010 East Asian Studies Graduate Student Conference in Toronto, the 2010 Women in Asia Conference in Canberra, and the 2011 Japanese Studies Association of Australia Conference in Melbourne. Date: ___________________. Signed: __________________. Emerald L King ii Authority of Access This thesis is not to made available for loan or copying for two years following the date this statement was signed. Following that time the thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Date: ___________________. Signed: __________________. Emerald L King iii Statement of Ethical Conduct “The research associated with this thesis abides by the international and Australian codes on human and animal experimentation, the guidelines by the Australian Government's Office of the Gene Technology Regulator and the rulings of the Safety, Ethics and Institutional Biosafety Committees of the University.” Date: ___________________. -

Snakes and Earrings Free

FREE SNAKES AND EARRINGS PDF Hitomi Kanehara | 128 pages | 02 Jun 2005 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099483670 | English | London, United Kingdom Snakes and Earrings | Netflix Lui is nineteen years old, beautiful, bored and unmotivated. When she meets Ama in a bar, she finds herself mesmerized by his forked tongue and moves in with him and has her own tongue pierced. Determined to push her boundaries further, she asks Amas friend Shiba to design an exquisite tattoo for her back. But what Snakes and Earrings demands as payment for the tattoo leads Lui into a brutal and explicit love triangle like no other. Then, after a violent encounter on the backstreets of Tokyo, Ama vanishes and Lui must face up to the reality of her life. Snakes and Earrings Hebi ni piasu is a based on the novel Snakes and Earrings the same name by then 21 year old writer Hitomi Kanehara. The novel went on to win the prestigious Akutagawa Prize and sold a million copies. MDL v6 en. TV Shows. Feeds Lists Forums Contributors. Edit this Page Edit Information. Buy on Amazon. Add to List. Ratings: 6. Reviews: 3 users. Score: 6. Add Cast. Yoshitaka Yuriko Nakazawa Rui. Iura Arata Shiba. Kora Kengo Snakes and Earrings Amada Kazunori. Fujiwara Tatsuya Yokoyama Satoru. Sonim Yuri. Abiru Yu Maki. View all 5. Write Review. Other reviews by this user 0. Jan 4, Completed 0. Overall 9. Story 7. Was this review helpful to you? Yes No Cancel. May 11, Overall 7. View all. Add Recommendations. Snakes and Earrings Topic. Be the first to create a discussion for Snakes and Earrings. -

New Ways of Being in the Fiction of Yoshimoto Banana

SINGLE FRAME HEROICS: NEW WAYS OF BEING IN THE FICTION OF YOSHIMOTO BANANA Ph. D Thesis Martin Ramsay Swinburne University of Technology 2009 CONTENTS Legend............................................................................................................. 5 Disclaimer…………………………………………………………………... 6 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………. 7 Abstract ….…………………………………………………………………. 8 Introduction: A Literature of ‘Self-Help’………………………………… 9 Yoshimoto’s postmodern style…...………………………………………….. 11 Early success and a sense of impasse………………………………………... 15 A trans-cultural writer……………………………………………………….. 17 Rescuing literature from irrelevance………………………………………… 21 Chapter One: Women and Gender Roles in Contemporary Japanese Society………………………………………………………………………. 27 An historical overview ………………………………………….…………... 27 Nation building and changing ‘ideals of femininity’………………………... 30 The rise of the Modan Ga-ru (Modern Girl)………………………………… 32 The Post-War Experience ……………………………………….………….. 37 The emergence of the ‘parasite single’……………………………………… 38 Women’s magazines and changing ‘ideals of femininity’…………………... 41 The Women’s Liberation movement……………………………….………... 44 Fear of the young: The politics of falling birth rates……..………………….. 47 Chapter Two: Yoshimoto Banana and Contemporary Japanese Literature…....…………………………………………………………….. 53 Japanese literature, women and modernity …………………………………. 54 The problem with popular culture …………………………….…………….. 62 2 Sh ôjo culture: the ‘baby-doll face of feminism’ in Japan……..……………. 70 A global literature and a shared -

GLOBAL CHILLING the Impact of Mass Surveillance on International Writers

The Impact of Mass Surveillance on International Writers GLOBAL CHILLING The Impact of Mass Surveillance on International Writers Results from PEN’s International Survey of Writers January 5, 2015 1 Global Chilling The Impact of Mass Surveillance on International Writers Results from PEN’s International Survey of Writers January 5, 2015 © PEN American Center 2015 All rights reserved PEN American Center is the largest branch of PEN International, the world’s leading literary and human rights organization. PEN works in more than 100 countries to protect free expression and to defend writers and journalists who are imprisoned, threatened, persecuted, or attacked in the course of their profession. PEN America’s 3700 members stand together with more than 20,000 PEN writers worldwide in international literary fellowship to carry on the achievements of such past members as James Baldwin, Robert Frost, Allen Ginsberg, Langston Hughes, Arthur Miller, Eugene O’Neill, Susan Sontag, and John Steinbeck. For more information, please visit www.pen.org. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 PRESENTATION OF KEY FINDINGS 7 RECOMMENDATIONS 15 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 17 METHODOLOGY 18 APPENDIX: PARTIAL SURVEY RESULTS 24 NOTES 35 GLOBAL CHILLING From August 28 to October 15, 2014, INTRODUCTION PEN American Center carried out an international survey of writers1, to in- vestigate how government surveillance influences their thinking, research, and writing, as well as their views of gov- ernment surveillance by the U.S. and its impact around the world. The survey instrument was developed and overseen by the nonpartisan expert survey research firm The FDR Group.2 The survey yielded 772 responses from writers living in 50 countries. -

Look at Me: Japanese Women Writers at the Millennial Turn David Holloway Washington University in St

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-22-2014 Look at Me: Japanese Women Writers at the Millennial Turn David Holloway Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Holloway, David, "Look at Me: Japanese Women Writers at the Millennial Turn" (2014). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1236. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1236 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN SAINT LOUIS Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures Dissertation Examination Committee: Rebecca Copeland, Chair Nancy Berg Marvin Marcus Laura Miller Jamie Newhard Look at Me: Japanese Women Writers at the Millennial Turn by David Holloway A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2014 Saint Louis, MO TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. iii INTRODUCTION: Ways of Looking. 1 CHAPTER ONE: Apocalypse and Anxiety in Contemporary Japan. 12 CHAPTER TWO: Repurposing Panic. 49 CHAPTER THREE: Writing Size Zero. 125 CHAPTER FOUR: The Dark Trauma. 184 CONCLUSION: Discourses of Disappointment, Heuristics of Happiness. 236 WORKS CITED. 246 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS If any credit is deserved for the completion of this dissertation, it is not I who deserve it. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax OMB No

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY - STATE REGISTRATION NO. 00-75-66 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2012 Department of the Treasury Open to Public Internal Revenue Service | The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. Inspection A For the 2012 calendar year, or tax year beginning and ending B Check if C Name of organization D Employer identification number applicable: Address change PEN AMERICAN CENTER, INC. Name change Doing Business As 13-3447888 Initial return Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Termin- ated 588 BROADWAY 303 (212)334-1660 Amended return City, town, or post office, state, and ZIP code G Gross receipts $ 4,792,345. Applica- tion NEW YORK, NY 10012-5246 H(a) Is this a group return pending F Name and address of principal officer:SUZANNE NOSSEL for affiliates? Yes X No SAME AS C ABOVE H(b) Are all affiliates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: X 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( )§ (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If "No," attach a list. (see instructions) J Website: | WWW.PEN.ORG H(c) Group exemption number | K Form of organization: X Corporation Trust Association Other | L Year of formation: 1985 M State of legal domicile: NY Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities: PEN AMERICAN CENTER, INC. -

The Holocaust As Public History

The University of California at San Diego HIEU 145 Course Number 646637 The Holocaust as Public History Winter, 2009 Professor Deborah Hertz HSS 6024 858 534 5501 Class meets 12---12:50 in Center 113 Please do not send me email messages. Best time to talk is right after class. It is fine to call my office during office hours. You may send a message to me on the Mail section of our WebCT. You may also get messages to me via Ms Dorothy Wagoner, Judaic Studies Program, 858 534 4551; [email protected]. Office Hours: Wednesdays 2-3 and Mondays 11-12 Holocaust Living History Workshop Project Manager: Ms Theresa Kuruc, Office in the Library: Library Resources Office, last cubicle on the right [turn right when you enter the Library] Phone: 534 7661 Email: [email protected] Office hours in her Library office: Tuesdays and Thursdays 11-12 and by appointment Ms Kuruc will hold a weekly two hour open house in the Library Electronic Classroom, just inside the entrance to the library to the left, on Wednesday evenings from 5-7. Students who plan to use the Visual History Archive for their projects should plan to work with her there if possible. If you are working with survivors or high school students, that is the time and place to work with them. Reader: Mr Matthew Valji, [email protected] WebCT The address on the web is: http://webct.ucsd.edu. Your UCSD e-mail address and password will help you gain entry. Call the Academic Computing Office at 4-4061 or 4-2113 if you experience problems. -

The Polish Journal of Aesthetics

The Polish Journal of Aesthetics The Polish Journal of Aesthetics 55 (4/2019) Jagiellonian University in Kraków The Polish Journal of Aesthetics Editor-in-Chief: Leszek Sosnowski Editorial Board: Dominika Czakon (Deputy Editor), Natalia Anna Michna (Deputy Editor), Anna Kuchta (Secretary), Marcin Lubecki (Editorial layout & Typesetting), Gabriela Matusiak, Adrian Mróz Advisory Board: Władysław Stróżewski (President of Advisory Board), Tiziana Andino, Nigel Dower, Saulius Geniusas, Jean Grondin, Carl Humphries, Ason Jaggar, Dalius Jonkus, Akiko Kasuya, Carolyn Korsmeyer, Leo Luks, Diana Tietjens Meyers, Carla Milani Damião, Mauro Perani, Kiyomitsu Yui Contact: Institute of Philosophy, Jagiellonian University 52 Grodzka Street, 31-004 Kraków, Poland [email protected], www.pjaesthetics.uj.edu.pl Published by: Institute of Philosophy, Jagiellonian University 52 Grodzka Street, 31-004 Kraków Co-publisher: Wydawnictwo Nowa Strona – Marcin Lubecki 22/43 Podgórze Street, 43-300 Bielsko-Biała Academic Journals www.academic-journals.eu Cover Design: Katarzyna Migdał On the Cover: Takahashi Hiroshi, Playing with a cat, 1930 First Edition © Copyright by Jagiellonian University in Kraków All rights reserved e-ISSN 2544-8242 CONTENTS Articles SARAH REBECCA Rotting Bodies: Sex, Gender, and Horror SCHMID in Tōkaidō Yotsuya Kaidan 9 AIMEN REMIDA Dialectical & Beautiful Harmony. A Sexuality-based Interpretation of Reiwa 令和 27 THOMAS SCHMIDT The Depiction of Japanese Homosexuality through Masks and Mirrors. An Observational Analysis of Funeral Parade of Roses 45 GRZEGORZ KUBIŃSKI Dolls and Octopuses. The (In)human Sexuality of Mari Katayama 63 LOUISE BOYD Women in shunga: Questions of Objectification and Equality 79 JARREL DE MATAS When No Means Yes: BDSM, Body Modification, and Japanese Womanhood as Monstrosity in Snakes and Earrings and Hotel Iris 101 About the Contributors 117 55 (4/2019), pp. -

A Genealogist Reveals the Painful Truth About Three Holocaust Memoirs: They’Re Fiction

discrepancies among names and dates in different translations helped to reveal the author’s true identity. A genealogist reveals the painful truth about three Holocaust memoirs: they’re fiction Untrue Stories BY cAleB dAniloff Detractors have called Sharon Sergeant a witch-hunter, a Holocaust denier, and even a Nazi. 32 BOSTONIA Summer 2009 PHOTograph by vernon doucette Summer 2009 BOSTONIA 33 In her 1997 autobiography, Misha: A Memoire The tools of her profession include photographic timelines and data- of the Holocaust Years, Belgian-born Misha bases — vital records, census reports, Defonseca claimed to have trekked war- property deeds, maps, newspaper interviews, obituaries, phone direc- pocked Europe for four years, starting at the tories — and living relatives. Skype, online records, and blogs have also age of seven, in search of her deported Jewish broadened her reach, and DNA testing parents. Along the way, she wrote, she took up is an option if she needs it. “The generic view of genealogy with a pack of wolves, slipped in and out of the is that it is about tracing relatives, the ‘begats,’” says Sergeant, a board Warsaw Ghetto, and killed a Nazi soldier. member and former programs director with the Massachusetts Genealogical In Europe, the book was a smash, court’s decision by proving the author Council. “It’s evolved.” translated into eighteen languages was a fraud. But her involvement in cracking and made into a hit film. In the It was there online, one day in open three Holocaust hoaxes is about United States, however, it had sold December 2007, that Sharon Sergeant more than an interest in the latest poorly — so poorly that Defonseca (MET’83), now an adjunct faculty technology. -

Diplomarbeit FINAL!

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „The ‘Third Reich’ memoir in the light of postmodern philosophy: historical representability and the gate- keeper’s task of ‘poetry after Auschwitz’“ Verfasserin Christine Schranz angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuerin: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Margarete Rubik Declaration of Authenticity I confirm to have conceived and written this paper in English all by myself. Quotation from sources are all clearly marked and acknowledged in the bibliographical references either in the footnotes or within the text. Any ideas borrowed and/or passages paraphrased from the works of other authors are truthfully acknowledged and identified in the footnotes. Christine Schranz Hinweis Diese Diplomarbeit hat nachgewiesen, dass die betreffende Kandidatin befähigt ist, wissenschaftliche Themen selbstständig sowie inhaltlich und methodisch vertretbar zu bearbeiten. Da die Korrekturen der Beurteilenden nicht eingetragen sind und das Gutachten nicht beiliegt, ist daher nicht erkenntlich, mit welcher Note diese Arbeit abgeschlossen wurde. Das Spektrum reicht von sehr gut bis genügend. Es wird gebeten, diesen Hinweis bei der Lektüre zu beachten. Acknowledgments Writing this thesis has been challenging and rewarding, and along the way I have been fortunate enough to have the help of friends and mentors. I would like to thank the following people for their contributions: Professor Rubik for trusting me on an “outside the box” topic, for pointing me in the right direction, for her editing and for many helpful suggestions. Doron Rabinovici for sharing his thoughts and research on history and fiction with me in an inspiring interview.