1 Chapter 5. Olga Kalacheva, Looking for the Common and the Public in A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surface Runoff to the Black Sea from the East European Plain During Last Glacial Maximum–Late Glacial Time

Downloaded from specialpapers.gsapubs.org on September 18, 2012 The Geological Society of America Special Paper 473 2011 Surface runoff to the Black Sea from the East European Plain during Last Glacial Maximum–Late Glacial time Aleksey Yu. Sidorchuk Andrey V. Panin Geographical Faculty, Moscow State University, Vorob’evy Gory, Moscow 119991, Russia Olga K. Borisova Institute of Geography, Russian Academy of Sciences, Staromonetny per., Moscow 119017, Russia ABSTRACT Hydromorphological and hydroclimatic methods were used to reconstruct the former surface runoff from the East European part of the Black Sea drainage basin. Data on the shape and dynamics of the last Fennoscandian ice sheet were used to cal- culate meltwater supply to the headwaters of the Dnieper River. The channel width and meander wavelength of well-preserved fragments of large paleochannels were measured at 51 locations in the Dnieper and Don River basins (East European Plain), which allowed reconstruction of the former surface runoff of the ancient rivers, as well as the total volume of fl ow into the Black Sea, using transform functions. Studies of the composition of fossil fl oras derived from radiocarbon-dated sediments of vari- ous origins and ages make it possible to locate their modern region analogues. These analogues provide climatic and hydrological indexes for the Late Pleniglacial and Late Glacial landscapes. Morphological, geological, geochronological, and palyno- logical studies show that the landscape, climatic, and hydrologic history of the region included: -

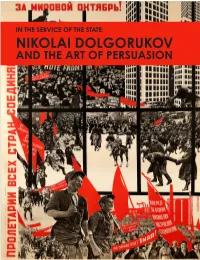

Nikolai Dolgorukov

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology. -

Peasants “On the Run”: State Control, Fugitives, Social and Geographic Mobility in Imperial Russia, 1649-1796

PEASANTS “ON THE RUN”: STATE CONTROL, FUGITIVES, SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHIC MOBILITY IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA, 1649-1796 A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Andrey Gornostaev, M.A. Washington, DC May 7, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Andrey Gornostaev All Rights Reserved ii PEASANTS “ON THE RUN”: STATE CONTROL, FUGITIVES, SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHIC MOBILITY IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA, 1649-1796 Andrey Gornostaev, M.A. Thesis Advisers: James Collins, Ph.D. and Catherine Evtuhov, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the issue of fugitive peasants by focusing primarily on the Volga-Urals region of Russia and situating it within the broader imperial population policy between 1649 and 1796. In the Law Code of 1649, Russia definitively bound peasants of all ranks to their official places of residence to facilitate tax collection and provide a workforce for the nobility serving in the army. In the ensuing century and a half, the government introduced new censuses, internal passports, and monetary fines; dispatched investigative commissions; and coerced provincial authorities and residents into surveilling and policing outsiders. Despite these legislative measures and enforcement mechanisms, many thousands of peasants left their localities in search of jobs, opportunities, and places to settle. While many fugitives toiled as barge haulers, factory workers, and agriculturalists, some turned to brigandage and river piracy. Others employed deception or forged passports to concoct fictitious identities, register themselves in villages and towns, and negotiate their status within the existing social structure. -

Circumpolar Wild Reindeer and Caribou Herds DRAFT for REVIEW

CircumpolarCircumpolar WildWild ReindeerReindeer andand CaribouCaribou HerdsHerds DRAFTDRAFT FORFOR REVIEWREVIEW 140°W 160°W 180° 160°E Urup ALEUTIAN ISLANDS NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN KURIL ISANDS Paramushir ALEUTIAN ISLANDS Petropavlovsk Kamchatskiy Commander Islands Bering Sea Kronotskiy Gulf r ive Gulf of Kamchatka a R k 50°N at ch NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN m Ka 40°N Sea of Okhotsk Bristol Bay KAMCHATKA PENINSULA Karaginskiy Gulf Okha ALASKA PENINSULA Tatar Strait Kodiak Gulf of Sakhalin Bethel Iliamna Lake Shelikhova Gulf P’yagina Pen. Koni Pen. Riv Homer ina er iver zh Magadan Cook Inlet R n m Pe Taygonos Pen. wi Coos Bay ok sk u Kenai K Kotlit S . F Gulf of Anadyr' Okhotsk-Kolyma Upland Kenai Peninsula o Western Arctic Wi r Uda Bay llam Anchorage k iver Eugenee Ku r’ R tt Tillamook Gulf of Alaska sk dy e S o Nome A na R Prince William Sound kw Salem2iv Queen Charlotte Islands u im s e Astoria Palmeri R Norton Sound ive r t iv R r STANOVOY RANGE n e a r a Valdez m Portland2 R y r Aberdeen2 Port HardyQueen Charlotte Sound i l e Dixon Entrance v o v Vancouver1 e CHUKCHI PENINSULA K i r R y r Centralia Bering Strait O u e Sitka l t v Olympia Seward Peninsula o h i ALASKA RANGE y R k R Courtenay ive u ia KetchikanAlexander Archipelago r K b TacomaStrait of Juan de Fuca Nanaimo m r Bol’sho u e y l A Wrangell v n o Puget Sound Strait of Georgia i United States of America yu C SeattleEverett R y r er Kotzebue Sound Ri e Juneau p ve iv BellinghamVancouver2 S op r R Yakima t C Kotzebue n ik r o COAST MOUNTAINS in e l COLUMBIA PLAT. -

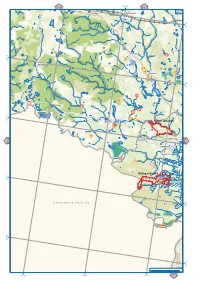

Atlas of High Conservation Value Areas, and Analysis of Gaps and Representativeness of the Protected Area Network in Northwest R

34°40' 216 217 Chudtsy Efimovsky 237 59°30' 59°20' Anisimovo Loshchinka River Somino Tushemelka River 59°20' Chagoda River Golovkovo Ostnitsy Spirovo 59°10' Klimovo Padun zakaznik Smordomsky 238 Puchkino 236 Ushakovo Ignashino Rattsa zakaznik 59°0' Rattsa River N O V G O R O D R E G I O N 59°0' 58°50' °50' 58 0369 км 34°20' 34°40' 35°0' 251 35°0' 35°20' 217 218 Glubotskoye Belaya Velga 238 protected mire protected mire Podgornoye Zaborye 59°30' Duplishche protected mire Smorodinka Volkhovo zakaznik protected mire Lid River °30' 59 Klopinino Mountain Stone protected mire (Kamennaya Gora) nature monument 59°20' BABAEVO Turgosh Vnina River °20' 59 Chadogoshchensky zakaznik Seredka 239 Pervomaisky 237 Planned nature monument Chagoda CHAGODA River and Pes River shores Gorkovvskoye protected mire Klavdinsky zakaznik SAZONOVO 59°10' Vnina Zalozno Staroye Ogarevo Chagodoshcha River Bortnikovo Kabozha Pustyn 59°0' Lake Chaikino nature monument Izbouishchi Zubovo Privorot Mishino °0' Pokrovskoye 59 Dolotskoye Kishkino Makhovo Novaya Planned nature monument Remenevo Kobozha / Anishino Chernoozersky Babushkino Malakhovskoye protected mire Kobozha River Shadrino Kotovo protected Chikusovo Kobozha mire zakazhik 58°50' Malakhovskoye / Kobozha 0369 protected mire км 35°20' 251 35°40' 36°0' 252 36°0' 36°20' 36°40' 218 219 239 Duplishche protected mire Kharinsky Lake Bolshoe-Volkovo zakaznik nature monument Planned nature monument Linden Alley 59°30' Pine forest Sudsky, °30' nature monument 59 Klyuchi zakaznik BABAEVO абаево Great Mosses Maza River 59°20' -

To Geophysical Abstracts 176-179 1959

Index to Geophysical Abstracts 176-179 1959 y DOROTHY B. VITALIANO and others EOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1106-E 1bstracts of current literature ertaining to the physics of ze solid earth and to eophysical exploration ITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1960 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington 25, D.C.-Price 35 cents. The printing of this publication has been approved by the Director of the Bureau of the Budget (December 5., 1957). INDEX TO GEOPHYSICAL ABSTRACTS 176-179, 1959 By DoROTHY B. VITALIANO and others AUTHOR INDEX A Abstract Abakeliya, M. S. The problem of geological interpretation of the regional gravity field of the Transcaucasian depression--------------------------------- 177-217 A:be, Siro. Morphology of .sse and SSC* -------------------------------- 179-298 Abel'skiy, M. Ye. The determination of the moment of inertia and centrifugal . moment of the torsion weight of the gravitati<mal variometer S-20________ 176-187 Acheson, C. H. The correction of seismic time maps for lateral variation in velocity beneath the low velocity layer------------------------------ 179-360 Acimovic, Ljubomir. See Ivkovic, Dragiiia Adachi, Ryuzo. A method of analysis of seismic refraction exploration______ 176-319 ---A solution of separation surface on the seismic reflection method (General case in three dimensional space)-------------------------------------- 176-318 ---On the singular point of time-distance curve __________________________ 176-315 Adam, Antal. On a modified telluric prospecting apparatus and its application to large-scale telluric investigations------~------------------------------- 176-21> Adamczewski, Ignacy. On natural and artificial radioactive contamination of the air and water------------------------------------------------------ 176-297 Adem, Julian. -

Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation, Using

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kazan Federal University Digital Repository Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation, using equipment purchased under the Development Program of Lomonosov Moscow State University (MSU), Grant Agreement No. 14.607.21.0187 of September 26 2017 (Unique Identifier of the Agreement: RFMEFI60717X0187). NEW DATA ON THE RESULTS OF THE MOLOGA-SHEKSNA LOWLAND LAKES RESEARCH (VOLOGDA REGION, RUSSIA) Sadokov D.O.1, 2, Sapelko T.V.3, Bobrov N.Y.2, Terekhov A.V.3 1Darwin State Nature Biosphere Reserve, Cherepovets, Russia 2Saint-Petersburg State University, Saint-Petersburg, Russia 3Institute of Limnology RAS, Saint-Petersburg, Russia Scandinavian ice sheet deglaciation is closely connected with forming and dynamics of the Gla- cial Lakes in Upper Valday period. Mologa-Sheksna Lake was one of the Largest Glacial Lakes on the north-west of East-European Plane with an approximate area 23 282,84 km2 (calculated by the altitude of the lacustrine terrace 140-152 m) (Anisimov et al., 2016). The Mologa-Sheksna Lowland was covered by an ice sheet during Late-Pleistocene period, which reached it maximal boundaries ap- proximately 19-18 thousand years ago, according to a range of radiocarbon and OSL dates (Hughes et al., 2016 ). Most of the ice-margin relief patterns are poorly developed or even absent in the region which makes it difficult to specify the ice sheet true boundaries during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). Glacial sediments and moraines are overlaid by lake and lake-glacial sediments, and the material could have been distributed by floating ice masses (Kvasov, 1975). -

13Th Centuries: Archaeological Evidence and Written Sources

Slavica Helsingiensia 27 The Slavicization of the Russian North. Mechanisms and Chronology. Ed. by Juhani Nuorluoto. Die Slavisierung Nordrusslands. Mechanismen und Chronologie. Hrsg. von Juhani Nuorluoto. Славянизация Русского Севера. Mеханизмы и хронология. Под ред. Юхани Нуорлуото. Helsinki 2006 ISBN 952–10–2852–1, ISSN 0780–3281; ISBN 952–10–2928–5 (PDF) N.A. Makarov (Moscow) Cultural Identity of the Russian North Settlers in the 10th – 13th Centuries: Archaeological Evidence and Written Sources One of the most critically important phenomena that determined the ethnic map of the North of Eastern Europe in the Modern time was the interaction of the Slavs and the Finns, as now perceived. Proceeding from the concepts of the ethno-cultural history of Eastern Europe, commonly approved by modern scholarship, this interaction may be supposed to have been especially intensive in the 10th – 13th centuries. This interaction was also marked by the wide-scale colonisation of northern territories, important social transformations and the establishment of new state and administrative structures. The ethno-geographic introduction to the Primary Chronicle by the time of compiling the narration calls the Finnish tribes ‘the first settlers’ in the towns and lands incorporated into the structure of Northern Rus’ (Polnoe sobranie russkix letopisej I: 10–11; II: 8–9). This information is accompanied by the abundant place-name data which is of Finno-Ugrian origin and which was registered in a major part of northern territories that by the 12th century had been integrated into the Novgorod and Rostov-Suzdal’ lands (Matveev 2001; Matveev 2004). Taken together, these data determine the general content of the ethno-cultural shifts nd that occurred in the early 2 millennium AD, but at the same time, give scope to the different interpretations as for the real character of the phenomenon known in the nineteenth century historiography as ‘Slavic colonisation’. -

La Suède Et L'orient, Études Archéologiques Sur Les Relations De

LA SUÈDE ET L'ORIENT ÉTUDES ARCHÉOLOGIQUES SUR LES RELATIONS DE LA SUÈDE ET DE L'ORIENT PENDANT L'ÂGE DES VIKINGS T. J. ARNE CNv/^ UPPSALA 1914 K. W. APPELBERGS BOKTRYCKERI i A LA SUÈDE ET L'ORIENT ÉTUDES ARCHÉOLOGIQUES SUR LES RELATIONS DE LA SUEDE ET DE L'ORIENT PENDANT L'ÂGE DES VIKINGS THESE POUR LE DOCTORAT PRÉSENTÉE À LA FACLTTÉ DES LETTRES D' UPSAL ET PUBLIQUEMENT SOUTENUE LE 25 MAI 1914, DÈS X HEURES DU MATIN DANS LA SALLE N" IV T. J. ARNE UPPSALA (914 K. W. APPELBÇRGS B O K T li V C K K l( I < Préface. Il y a environ deux ans que la première partie de cette étude a été mise sous presse; cependant la publication a été retardée par un voyage en Russie, de 14 mois, qui m'a fourni, il est vrai, quantité de matériaux nouveaux, mais qui a aussi causé un certain manque d'unité dans la conception de mon ouvrage. A la première partie, qui traite des objets Scandinaves trouvés en Russie, j'ai bien pu ajouter des notices sur les matériaux non publiés qui sont con- serves dans les musées de Russie, mais il m'a été impossible de remanier tout à fait cette partie, ce qui en aurait doublé plusieurs fois le volume. Pour les objets de provenance orientale, importés en Suède, je n'ai pu non plus faire usage de tous mes matériaux. On ne saurait se faire une idée nette du rôle qu'ont joué en Russie les Suédois de l'ère des vikings, tel qu'il se révèle dans les trouvailles russes de provenance Scandinave, que par une com- paraison statistique de celles-ci, d'abord avec les objets trouvés en Scandinavie, puis avec ceux de provenance finnoise, slave, etc. -

The Case Study for the European Part of Russia)

Hydrology in a Changing World: Environmental and Human Dimensions 113 Proceedings of FRIEND-Water 2014, Montpellier, France, October 2014 (IAHS Publ. 363, 2014). Up-to-date climate forced seasonal flood changes (the case study for the European part of Russia) NATALIA FROLOVA, MARIA KIREEVA, DMITRY NESTERENKO, SVETLANA AGAFONOVA & PAVEL TERSKY Department of Hydrology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, 119899, Leninskiye Gory, Moscow, Russia [email protected] Abstract The analysis of hydrological information for the observation period (1946–2010) based on data from more than 200 hydrological stations enabled the evaluation of changes in characteristics of a spring flood in the rivers of the European territory of Russia and the determination of flood characteristic factors. In addition, changes of climatic characteristics such as the increase in number of winter thaws and the precipitation total in the cold season have been related to features of spatial and temporal variability of the beginning and end dates of the spring flood, maximum water discharges and shapes of hydrographs, and volume of runoff during a spring high-water period. Key words flood; water regime; climate change; European part of Russia INTRODUCTION Spring flood as a phase of the water regime plays an important role in the formation of river runoff in the European territory of Russia (ETR). It determines potential water supply during the summer–autumn low water period and the character of rain-fed flash floods. The main reason for change of river runoff in different seasons of the year lies in the change of climate resulting in changes of atmospheric circulation in the study region. -

What the North Caucasus Means to Russia

What the North Caucasus Means to Russia Alexey Malashenko July 2011 Russia/NIS Center Ifri is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debates and research activities. The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ alone and do not reflect the official views of their institutions. Russia/NIS Center © All rights reserved – Ifri – Paris, 2011 ISBN: 978-2-86592-865-1 IFRI IFRI-Bruxelles 27 RUE DE LA PROCESSION RUE MARIE-THERESE, 21 75740 PARIS CEDEX 15 – FRANCE 1000 BRUXELLES TEL. : 33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 TEL. : 32(2) 238 51 10 FAX : 33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 FAX : 32 (2) 238 51 15 E-MAIL : [email protected] E-MAIL : [email protected] WEBSITE : www.ifri.org A. Malashenko / North Caucasus Russie.Nei.Visions Russie.Nei.Visions is an online collection dedicated to Russia and the other new independent states (Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan). Written by leading experts, these policy-oriented papers deal with strategic, political and economic issues. -

Sedition : Everyday Resistance in the Soviet Union Under Khrushchev and Brezhnev / Edited by Vladimir A

annals of communism Each volume in the series Annals of Communism will publish selected and previ- ously inaccessible documents from former Soviet state and party archives in a nar- rative that develops a particular topic in the history of Soviet and international communism. Separate English and Russian editions will be prepared. Russian and Western scholars work together to prepare the documents for each volume. Doc- uments are chosen not for their support of any single interpretation but for their particular historical importance or their general value in deepening understanding and facilitating discussion. The volumes are designed to be useful to students, scholars, and interested general readers. executive editor of the annals of communism series Jonathan Brent, Yale University Press project manager Vadim A. Staklo american advisory committee Ivo Banac, Yale University Robert L. Jackson, Yale University Zbigniew Brzezinski, Center for Norman Naimark, Stanford Univer- Strategic and International Studies sity William Chase, University of Pittsburgh Gen. William Odom (deceased), Hud- Friedrich I. Firsov, former head of the son Institute and Yale University Comintern research group at Daniel Orlovsky, Southern Methodist RGASPI University Sheila Fitzpatrick, University of Timothy Snyder, Yale University Chicago Mark Steinberg, University of Illinois, Gregory Freeze, Brandeis University Urbana-Champaign John L. Gaddis, Yale University Strobe Talbott, Brookings Institution J. Arch Getty, University of California, Mark Von Hagen, Arizona State Uni- Los Angeles versity Jonathan Haslam, Cambridge Univer- Piotr Wandycz, Yale University sity russian advisory committee K. M. Anderson, Moscow State Uni- S. V. Mironenko, director, State versity Archive of the Russian Federation N. N. Bolkhovitinov, Russian Acad- (GARF) emy of Sciences O.