13Th Centuries: Archaeological Evidence and Written Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characteristics of the Regime and Structure of Water Masses in the Volga Reservoirs

Characteristics of the regime and structure of water masses in the Volga reservoirs N. V. Butorin Abstract. The characteristics of the hydrological regime of reservoirs is shown in peculiarities of the water balance, water circulation, level, wave, temperature and ice regimes. The peculiarities of the hydrological regime lead to heterogeneity in the physical and chemical characteristics of the water. Detailed analysis of these characteristics makes it possible to identify distinct water masses with different properties in reservoirs. Resume. Los traits spécifiques du regime hydrologique des reservoirs se manifestent dans les particularités du bilan hydrologique, de la circulation de l'eau et dans les particularités des régimes des vagues, des températures et des glaces. Ces particularités du régime hydrologique conduisent à l'hétérogénéité physique et chimique de la masse d'eau. L'analyse complexe des champs de ces caractéristiques nous permet d'établir la présence dans les réservoirs des masses d'eau présentant des particularités différentes. The use of natural water resources under modem technological progress is limited by the peculiarities of their geographical distribution, their seasonal and yearly fluctuations and also by considerable water pollution from domestic and industrial waste. One of the most effective means of controlling water resources is by creating reservoirs. Reservoirs are becoming an essential feature of the landscape. Each of them is a complex geographical object. Reservoirs differ from other water bodies in their bed morphology, in the interaction of the water mass with the bottom and the shores, in the physical and chemical properties of the waters and their dynamics, The main characteristic feature of a reservoir is its slow water exchange and the possibility of regulating it. -

Surface Runoff to the Black Sea from the East European Plain During Last Glacial Maximum–Late Glacial Time

Downloaded from specialpapers.gsapubs.org on September 18, 2012 The Geological Society of America Special Paper 473 2011 Surface runoff to the Black Sea from the East European Plain during Last Glacial Maximum–Late Glacial time Aleksey Yu. Sidorchuk Andrey V. Panin Geographical Faculty, Moscow State University, Vorob’evy Gory, Moscow 119991, Russia Olga K. Borisova Institute of Geography, Russian Academy of Sciences, Staromonetny per., Moscow 119017, Russia ABSTRACT Hydromorphological and hydroclimatic methods were used to reconstruct the former surface runoff from the East European part of the Black Sea drainage basin. Data on the shape and dynamics of the last Fennoscandian ice sheet were used to cal- culate meltwater supply to the headwaters of the Dnieper River. The channel width and meander wavelength of well-preserved fragments of large paleochannels were measured at 51 locations in the Dnieper and Don River basins (East European Plain), which allowed reconstruction of the former surface runoff of the ancient rivers, as well as the total volume of fl ow into the Black Sea, using transform functions. Studies of the composition of fossil fl oras derived from radiocarbon-dated sediments of vari- ous origins and ages make it possible to locate their modern region analogues. These analogues provide climatic and hydrological indexes for the Late Pleniglacial and Late Glacial landscapes. Morphological, geological, geochronological, and palyno- logical studies show that the landscape, climatic, and hydrologic history of the region included: -

2018 FIFA WORLD CUP RUSSIA'n' WATERWAYS

- The 2018 FIFA World Cup will be the 21st FIFA World Cup, a quadrennial international football tournament contested by the men's national teams of the member associations of FIFA. It is scheduled to take place in Russia from 14 June to 15 July 2018,[2] 2018 FIFA WORLD CUP RUSSIA’n’WATERWAYS after the country was awarded the hosting rights on 2 December 2010. This will be the rst World Cup held in Europe since 2006; all but one of the stadium venues are in European Russia, west of the Ural Mountains to keep travel time manageable. - The nal tournament will involve 32 national teams, which include 31 teams determined through qualifying competitions and Routes from the Five Seas 14 June - 15 July 2018 the automatically quali ed host team. A total of 64 matches will be played in 12 venues located in 11 cities. The nal will take place on 15 July in Moscow at the Luzhniki Stadium. - The general visa policy of Russia will not apply to the World Cup participants and fans, who will be able to visit Russia without a visa right before and during the competition regardless of their citizenship [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2018_FIFA_World_Cup]. IDWWS SECTION: Rybinsk – Moscow (433 km) Barents Sea WATERWAYS: Volga River, Rybinskoye, Ughlichskoye, Ivan’kovskoye Reservoirs, Moscow Electronic Navigation Charts for Russian Inland Waterways (RIWW) Canal, Ikshinskoye, Pestovskoye, Klyaz’minskoye Reservoirs, Moskva River 600 MOSCOW Luzhniki Arena Stadium (81.000), Spartak Arena Stadium (45.000) White Sea Finland Belomorsk [White Sea] Belomorsk – Petrozavodsk (402 km) Historic towns: Rybinsk, Ughlich, Kimry, Dubna, Dmitrov Baltic Sea Lock 13,2 White Sea – Baltic Canal, Onega Lake Small rivers: Medveditsa, Dubna, Yukhot’, Nerl’, Kimrka, 3 Helsinki 8 4,0 Shosha, Mologa, Sutka 400 402 Arkhangel’sk Towns: Seghezha, Medvezh’yegorsk, Povenets Lock 12,2 Vyborg Lakes: Vygozero, Segozero, Volozero (>60.000 lakes) 4 19 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 30 1 2 3 6 7 10 14 15 4,0 MOSCOW, Group stage 1/8 1/4 1/2 3 1 Estonia Petrozavodsk IDWWS SECTION: [Baltic Sea] St. -

Nikolai Dolgorukov

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology. -

Peasants “On the Run”: State Control, Fugitives, Social and Geographic Mobility in Imperial Russia, 1649-1796

PEASANTS “ON THE RUN”: STATE CONTROL, FUGITIVES, SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHIC MOBILITY IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA, 1649-1796 A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Andrey Gornostaev, M.A. Washington, DC May 7, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Andrey Gornostaev All Rights Reserved ii PEASANTS “ON THE RUN”: STATE CONTROL, FUGITIVES, SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHIC MOBILITY IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA, 1649-1796 Andrey Gornostaev, M.A. Thesis Advisers: James Collins, Ph.D. and Catherine Evtuhov, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the issue of fugitive peasants by focusing primarily on the Volga-Urals region of Russia and situating it within the broader imperial population policy between 1649 and 1796. In the Law Code of 1649, Russia definitively bound peasants of all ranks to their official places of residence to facilitate tax collection and provide a workforce for the nobility serving in the army. In the ensuing century and a half, the government introduced new censuses, internal passports, and monetary fines; dispatched investigative commissions; and coerced provincial authorities and residents into surveilling and policing outsiders. Despite these legislative measures and enforcement mechanisms, many thousands of peasants left their localities in search of jobs, opportunities, and places to settle. While many fugitives toiled as barge haulers, factory workers, and agriculturalists, some turned to brigandage and river piracy. Others employed deception or forged passports to concoct fictitious identities, register themselves in villages and towns, and negotiate their status within the existing social structure. -

The Chronicle of Novgorod 1016-1471

- THE CHRONICLE OF NOVGOROD 1016-1471 TRANSLATED FROM THE RUSSIAN BY ROBERT ,MICHELL AND NEVILL FORBES, Ph.D. Reader in Russian in the University of Oxford WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY C. RAYMOND BEAZLEY, D.Litt. Professor of Modern History in the University of Birmingham AND AN ACCOUNT OF THE TEXT BY A. A. SHAKHMATOV Professor in the University of St. Petersburg CAMDEN’THIRD SERIES I VOL. xxv LONDON OFFICES OF THE SOCIETY 6 63 7 SOUTH SQUARE GRAY’S INN, W.C. 1914 _. -- . .-’ ._ . .e. ._ ‘- -v‘. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE General Introduction (and Notes to Introduction) . vii-xxxvi Account of the Text . xxx%-xli Lists of Titles, Technical terms, etc. xlii-xliii The Chronicle . I-zzo Appendix . 221 tJlxon the Bibliography . 223-4 . 225-37 GENERAL INTRODUCTION I. THE REPUBLIC OF NOVGOROD (‘ LORD NOVGOROD THE GREAT," Gospodin Velikii Novgorod, as it once called itself, is the starting-point of Russian history. It is also without a rival among the Russian city-states of the Middle Ages. Kiev and Moscow are greater in political importance, especially in the earliest and latest mediaeval times-before the Second Crusade and after the fall of Constantinople-but no Russian town of any age has the same individuality and self-sufficiency, the same sturdy republican independence, activity, and success. Who can stand against God and the Great Novgorod ?-Kto protiv Boga i Velikago Novgoroda .J-was the famous proverbial expression of this self-sufficiency and success. From the beginning of the Crusading Age to the fall of the Byzantine Empire Novgorod is unique among Russian cities, not only for its population, its commerce, and its citizen army (assuring it almost complete freedom from external domination even in the Mongol Age), but also as controlling an empire, or sphere of influence, extending over the far North from Lapland to the Urals and the Ob. -

Circumpolar Wild Reindeer and Caribou Herds DRAFT for REVIEW

CircumpolarCircumpolar WildWild ReindeerReindeer andand CaribouCaribou HerdsHerds DRAFTDRAFT FORFOR REVIEWREVIEW 140°W 160°W 180° 160°E Urup ALEUTIAN ISLANDS NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN KURIL ISANDS Paramushir ALEUTIAN ISLANDS Petropavlovsk Kamchatskiy Commander Islands Bering Sea Kronotskiy Gulf r ive Gulf of Kamchatka a R k 50°N at ch NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN m Ka 40°N Sea of Okhotsk Bristol Bay KAMCHATKA PENINSULA Karaginskiy Gulf Okha ALASKA PENINSULA Tatar Strait Kodiak Gulf of Sakhalin Bethel Iliamna Lake Shelikhova Gulf P’yagina Pen. Koni Pen. Riv Homer ina er iver zh Magadan Cook Inlet R n m Pe Taygonos Pen. wi Coos Bay ok sk u Kenai K Kotlit S . F Gulf of Anadyr' Okhotsk-Kolyma Upland Kenai Peninsula o Western Arctic Wi r Uda Bay llam Anchorage k iver Eugenee Ku r’ R tt Tillamook Gulf of Alaska sk dy e S o Nome A na R Prince William Sound kw Salem2iv Queen Charlotte Islands u im s e Astoria Palmeri R Norton Sound ive r t iv R r STANOVOY RANGE n e a r a Valdez m Portland2 R y r Aberdeen2 Port HardyQueen Charlotte Sound i l e Dixon Entrance v o v Vancouver1 e CHUKCHI PENINSULA K i r R y r Centralia Bering Strait O u e Sitka l t v Olympia Seward Peninsula o h i ALASKA RANGE y R k R Courtenay ive u ia KetchikanAlexander Archipelago r K b TacomaStrait of Juan de Fuca Nanaimo m r Bol’sho u e y l A Wrangell v n o Puget Sound Strait of Georgia i United States of America yu C SeattleEverett R y r er Kotzebue Sound Ri e Juneau p ve iv BellinghamVancouver2 S op r R Yakima t C Kotzebue n ik r o COAST MOUNTAINS in e l COLUMBIA PLAT. -

European River Lamprey Lampetra Fluviatilis in the Upper Volga: Distribution and Biology

European River Lamprey Lampetra Fluviatilis in the Upper Volga: Distribution and Biology Aleksandr Zvezdin AN Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution Aleksandr Kucheryavyy ( [email protected] ) AN Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2014-5736 Anzhelika Kolotei AN Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution Natalia Polyakova AN Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution Dmitrii Pavlov AN Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution Research Keywords: Petromyzontidae, behavior, invasion, distribution, downstream migration, upstream migration Posted Date: February 12th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-187893/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/19 Abstract After the construction of the Volga Hydroelectric Station and other dams, migration routes of the Caspian lamprey were obstructed. The ecological niches vacated by this species attracted another lamprey of the genus Lampetra to the Upper Volga, which probably came from the Baltic Sea via the system of shipways developed in the 18 th and 19 th centuries. Based on collected samples and observations from sites in the Upper Volga basin, we provide diagnostic characters of adults, and information on spawning behavior. Silver coloration of Lampetra uviatilis was noted for the rst time and a new size-related subsample of “large” specimens was delimited, in addition to the previously described “dwarf”, “small” and “common” adult resident sizes categories. The three water systems: the Vyshnii Volochek, the Tikhvin and the Mariinskaya, are possible invasion pathways, based on the migration capabilities of the lampreys. Dispersal and colonization of the Caspian basin was likely a combination of upstream and downstreams migrations. -

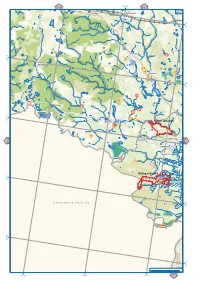

Atlas of High Conservation Value Areas, and Analysis of Gaps and Representativeness of the Protected Area Network in Northwest R

34°40' 216 217 Chudtsy Efimovsky 237 59°30' 59°20' Anisimovo Loshchinka River Somino Tushemelka River 59°20' Chagoda River Golovkovo Ostnitsy Spirovo 59°10' Klimovo Padun zakaznik Smordomsky 238 Puchkino 236 Ushakovo Ignashino Rattsa zakaznik 59°0' Rattsa River N O V G O R O D R E G I O N 59°0' 58°50' °50' 58 0369 км 34°20' 34°40' 35°0' 251 35°0' 35°20' 217 218 Glubotskoye Belaya Velga 238 protected mire protected mire Podgornoye Zaborye 59°30' Duplishche protected mire Smorodinka Volkhovo zakaznik protected mire Lid River °30' 59 Klopinino Mountain Stone protected mire (Kamennaya Gora) nature monument 59°20' BABAEVO Turgosh Vnina River °20' 59 Chadogoshchensky zakaznik Seredka 239 Pervomaisky 237 Planned nature monument Chagoda CHAGODA River and Pes River shores Gorkovvskoye protected mire Klavdinsky zakaznik SAZONOVO 59°10' Vnina Zalozno Staroye Ogarevo Chagodoshcha River Bortnikovo Kabozha Pustyn 59°0' Lake Chaikino nature monument Izbouishchi Zubovo Privorot Mishino °0' Pokrovskoye 59 Dolotskoye Kishkino Makhovo Novaya Planned nature monument Remenevo Kobozha / Anishino Chernoozersky Babushkino Malakhovskoye protected mire Kobozha River Shadrino Kotovo protected Chikusovo Kobozha mire zakazhik 58°50' Malakhovskoye / Kobozha 0369 protected mire км 35°20' 251 35°40' 36°0' 252 36°0' 36°20' 36°40' 218 219 239 Duplishche protected mire Kharinsky Lake Bolshoe-Volkovo zakaznik nature monument Planned nature monument Linden Alley 59°30' Pine forest Sudsky, °30' nature monument 59 Klyuchi zakaznik BABAEVO абаево Great Mosses Maza River 59°20' -

![Monthly Discharges for 2400 Rivers and Streams of the Former Soviet Union [FSU]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9027/monthly-discharges-for-2400-rivers-and-streams-of-the-former-soviet-union-fsu-2339027.webp)

Monthly Discharges for 2400 Rivers and Streams of the Former Soviet Union [FSU]

Annotations for Monthly Discharges for 2400 Rivers and Streams of the former Soviet Union [FSU] v1.1, September, 2001 Byron A. Bodo [email protected] Toronto, Canada Disclaimer Users assume responsibility for errors in the river and stream discharge data, associated metadata [river names, gauge names, drainage areas, & geographic coordinates], and the annotations contained herein. No doubt errors and discrepancies remain in the metadata and discharge records. Anyone data set users who uncover further errors and other discrepancies are invited to report them to NCAR. Acknowledgement Most discharge records in this compilation originated from the State Hydrological Institute [SHI] in St. Petersburg, Russia. Problems with some discharge records and metadata notwithstanding; this compilation could not have been created were it not for the efforts of SHI. The University of New Hampshire’s Global Hydrology Group is credited for making the SHI Arctic Basin data available. Foreword This document was prepared for on-screen viewing, not printing !!! Printed output can be very messy. To ensure wide accessibility, this document was prepared as an MS Word 6 doc file. The www addresses are not active hyperlinks. They have to be copied and pasted into www browsers. Clicking on a page number in the Table of Contents will jump the cursor to the beginning of that section of text [in the MS Word version, not the pdf file]. Distribution Files Files in the distribution package are listed below: Contents File name short abstract abstract.txt ascii description of -

To Geophysical Abstracts 176-179 1959

Index to Geophysical Abstracts 176-179 1959 y DOROTHY B. VITALIANO and others EOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1106-E 1bstracts of current literature ertaining to the physics of ze solid earth and to eophysical exploration ITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1960 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington 25, D.C.-Price 35 cents. The printing of this publication has been approved by the Director of the Bureau of the Budget (December 5., 1957). INDEX TO GEOPHYSICAL ABSTRACTS 176-179, 1959 By DoROTHY B. VITALIANO and others AUTHOR INDEX A Abstract Abakeliya, M. S. The problem of geological interpretation of the regional gravity field of the Transcaucasian depression--------------------------------- 177-217 A:be, Siro. Morphology of .sse and SSC* -------------------------------- 179-298 Abel'skiy, M. Ye. The determination of the moment of inertia and centrifugal . moment of the torsion weight of the gravitati<mal variometer S-20________ 176-187 Acheson, C. H. The correction of seismic time maps for lateral variation in velocity beneath the low velocity layer------------------------------ 179-360 Acimovic, Ljubomir. See Ivkovic, Dragiiia Adachi, Ryuzo. A method of analysis of seismic refraction exploration______ 176-319 ---A solution of separation surface on the seismic reflection method (General case in three dimensional space)-------------------------------------- 176-318 ---On the singular point of time-distance curve __________________________ 176-315 Adam, Antal. On a modified telluric prospecting apparatus and its application to large-scale telluric investigations------~------------------------------- 176-21> Adamczewski, Ignacy. On natural and artificial radioactive contamination of the air and water------------------------------------------------------ 176-297 Adem, Julian. -

1 Chapter 5. Olga Kalacheva, Looking for the Common and the Public in A

Chapter 5. Olga Kalacheva, Looking for the Common and the Public in a Town We live in the cities. The cities live in us… Time passes. We change… Everything changes. And fast. Images above all. Wim Wenders1 Introduction In 1980s a well-known German producer Wim Wenders made two documentary films, the subjects of which was connected with Tokyo. Having recently watched these films again, I came to the conlusion that the goal of this film director was largely similar to that of our present project. The first film, “Tokyo-Ga” is dedicated to the Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963) who made 54 films with detailed observations on the world of everyday life in Japan: 54 films as 54 sentences in a simple story “about the same people in the same city.”2 Wenders comes to this city of his cult-figure to find, in Tokyo of the 1980s, subjects and ideas worthy of Ozu films, where everybody could see a story of oneself and one’s own life. His camera captures transportation thoroughfares, trains, skyscrapers, famous Tokyo underground; café windows, decorated with wax food; a cemetery, where groups of people walk, eat, drink, and enjoy themselves under blossoming cherry-trees; Pachinko-playing machines that became popular in post-war Japan; a stadium, where hundreds of Tokyo citizens polish their golf skills… One could say that the film consists of relatively independent images, yet all of them together compose a unified mosaic of life in a contemporary city. Bruno Latour, reflecting upon his invisible Paris, observes that it is not easy to see this phenomenon; the city never appears as an image, yet it becomes visible in that which is transformed and transported from one image to another, from one point of view or perspective to the other one.