THE LIVERPOOL BLITZ, a PERSONAL EXPERIENCE. by Jim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEN (Organization)

PEN (Organization): An Inventory of Its Records at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: PEN (Organization) Title: PEN (Organization) Records Dates: 1912-2008 (bulk 1926-1997) Extent: 352 document boxes, 5 card boxes (cb), 5 oversize boxes (osb) (153.29 linear feet), 4 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The records of the London-based writers' organizations English PEN and PEN International, founded by Catharine Amy Dawson Scott in 1921, contain extensive correspondence with writer-members and other PEN centres around the world. Their records document campaigns, international congresses and other meetings, committees, finances, lectures and other programs, literary prizes awarded, membership, publications, and social events over several decades. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03133 Language: The records are primarily written in English with sizeable amounts in French, German, and Spanish, and lesser amounts in numerous other languages. Non-English items are sometimes accompanied by translations. Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation, cataloging, and selective digitization of this collection. The PEN Digital Collection contains 3,500 images of newsletters, minutes, reports, scrapbooks, and ephemera selected from the PEN Records. An additional 900 images selected from the PEN Records and related Ransom Center collections now form five PEN Teaching Guides that highlight PEN's interactions with major political and historical trends across the twentieth century, exploring the organization's negotiation with questions surrounding free speech, political displacement, and human rights, and with global conflicts like World War II and the Cold War. Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. -

Prof Michael Turner 18.10.17

Wednesday 18 October 2017 Michael Turner UNESCO Chair in Urban Design and Conservation Studies Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem 1945 - Why the conflict? • Utopias/visions • Values and interpretations • Generation gaps and changes • Competing interests • Process and project • Short-term / long-term • Lack of tools 1972 - Resolving/containing the conflict • Managing change • Accepting diversity • Sharing benefits • Participatory processes • Sustainable development • Inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable Utopia Wikipedia Thomas More William Morris Ebenezer Howard Utopia News from Nowhere To-morrow: 1516 1890 A Peaceful Path to Real Reform 1898 Liverpool – 19th century Industrial visions Port Sunlight Village 1888 wikipedia wikipedia Pinterest Liverpool Museum Liverpool Liverpool utopias – 20th century Wavertree Garden Suburb Speke Estate Runcorn New Town 1910 1930 1964 Wikipedia http://www.liverpool-city-group.com/ Rebuilding post WWII - utopias Wars Socio-economic changes The devastation in Liverpool docks after the ammunition ship The Albert Dock fell into disuse in the 1970s, as shown in the 1975 'Malakand' blew up after catching fire on the night of 3rd May 1941. snap above. Part of the Albert Dock failed to be restored from the damage of the Liverpool Blitz 1941. Once welcoming ships into the port every day, the docks are derelict, with not a sign of life to be seen. A year later, the Albert Dock was a conservation area. Signature’s Liverpool - source: www.porterfolio.com World War II reconstruction East Europe - Warsaw -

Military History Anniversaries 16 Thru 31 August

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 31 August Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Aug 16 1777 – American Revolution: Battle of Bennington » The Battle took place in Walloomsac, New York, about 10 miles from its namesake Bennington, Vermont. A rebel force of about 1,500 men, primarily New Hampshire and Massachusetts militiamen, led by General John Stark, and reinforced by Vermont militiamen led by Colonel Seth Warner and members of the Green Mountain Boys, decisively defeated a detachment of General John Burgoyne's army led by Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum, and supported by additional men under Lieutenant Colonel Heinrich von Breymann at Walloomsac, New York. After a rain-caused standoff, Brigadier General John Stark's men enveloped Baum's position, taking many prisoners, and killing Baum. Reinforcements for both sides arrived as Stark and his men were mopping up, and the battle restarted, with Warner and Stark driving away Breymann's reinforcements with heavy casualties. The battle reduced Burgoyne's army in size by almost 1,000 troops, led his Indian support to largely abandon him, and deprived him of much-needed supplies, such as mounts for his cavalry regiments, draft animals and provisions; all factors that contributed to Burgoyne's eventual defeat at the Battle of Saratoga. Aug 16 1780 – American Revolution: Continentals routed at Battle of Camden SC » American General Horatio Gates suffers a humiliating defeat. Despite the fact that his men suffered from diarrhea on the night of 15 AUG, caused by their consumption of under-baked bread, Gates chose to engage the British on the morning of the 15th. -

Liverpool Trade Walk

Stories from the sea A free self-guided walk in Liverpool .walktheworld.or www g.uk Find Explore Walk 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route overview 5 Practical information 6 Detailed maps 8 Commentary 10 Credits 38 © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2012 Walk the World is part of Discovering Places, the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad campaign to inspire the UK to discover their local environment. Walk the World is delivered in partnership by the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) with Discovering Places (The Heritage Alliance) and is principally funded by the National Lottery through the Olympic Lottery Distributor. The digital and print maps used for Walk the World are licensed to RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey. 3 Stories from the sea Discover how international trade shaped Liverpool Welcome to Walk the World! This walk in Liverpool is one of 20 in different parts of the UK. Each walk explores how the 206 participating nations in the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games have been part of the UK’s history for many centuries. Along the routes you will discover evidence of how many Olympic and Paralympic countries have shaped our towns and cities. Tea from China, bananas from Jamaica, timber from Sweden, rice from India, cotton from America, hemp from Egypt, sugar from Barbados... These are just some of the goods that arrived at Liverpool’s docks. In the A painting of Liverpool from circa 1680, nineteenth century, 40 per cent of the world’s thought to be the oldest existing depiction of the city trade passed through Liverpool. -

The Role of the Dungeon Master

06_783307 ch01.qxp 3/16/06 8:40 PM Page 9 Chapter 1 The Role of the Dungeon Master In This Chapter ᮣ Discovering the role of the Dungeon Master ᮣ Finding what you need to play D&D ᮣ Exploring the many expressions of Dungeon Mastering ᮣ Understanding the goals of Dungeon Mastering ou know what DUNGEONS & DRAGONS is. It’s the original roleplaying game, Ythe game that inspired not only a host of other roleplaying games, but most computer roleplaying games as well. A roleplaying game allows players to take on the roles of characters in a story of their own creation. Part improvisation, part wargame, the D&D game provides a wholly unique and unequalled experience. For a game such as D&D to work, one of the players in a group must take on a fun, exciting, creative, and extremely rewarding role — the role of Dungeon Master. Thanks to the presence of a Dungeon Master (DM), a D&D game can be more interactive than any computer game, more open-ended than any novel or movie. Using a fantastic world of medieval technology, magic, and monsters as a backdrop, the DM has the power of the game mechanics and the imagi- nation of all the players to work with. Whatever anyone can imagine can come to life in the game, thanks to the robust set of rules that are the heart of the D&D game. The rules and imagination can take your game only so far, however. The heights your game can reach and the fun you can have with it depend onCOPYRIGHTED the creativity and involvement MATERIAL of the Dungeon Master. -

Castillo De San Marcos Fort Matanzas

administrative history CASTILLO DE SAN MARCOS FORT MATANZAS NATIONAL MONUMENTS/FLORIDA ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY OF CASTILLO DE SAN MARCOS NATIONAL MONUMENT AND FORT MATANZAS NATIONAL MONUMENT by Jere L. Krakow July 1986 United States Department of the Interior / National Park Service CONTENTS Acknowledgements / v Chapter 1: War Department Administration, 1866-1914 / 1 Preservation Sentiment / 1 Growth of Tourism-Castillo / 4 Indian Incarceration / 6 ' Maintenance And Preservation / 7 Budget And Designated Appropriation / 8 Concern For Fort Matanzas / 9 Chapter 2: War Department Administration, 1914-1933 / 13 Government Initiatives / 13 First License-St. Augustine Historical Society / 14 Caretakers Brown And Davis / 16 Commercialization / 18 Surplus Forts / 21 Stabilize And Restore Fort Matanzas / 22 Declared National Monuments / 23 Quartermaster Department Management / 24 Management Controversy / 28 Competition For License, 1928 / 31 Final License, 1933 / 36 Chapter 3: The National Park Service: Administration 39 Tenure Begins / 39 Kahler Administration / 39 Freeland Administration / 51 Vinten Administration / 52 Roberts Administration / 59 Davenport Administration / 61 Schesventer Administration / 63 Aikens Administration / 65 Griffin Administration / 67 Chapter 4: The National Park Service: Programs and Relations / 69 Interpretation / 69 Special Events And Visitors / 79 Research / 83 History / 83 Archeology / 88 Natural Resources / 91 Race Relations / 91 Chapter 5: The National Park Service: Problems And Prospects / 95 Appendices / 101 A: Proclamation by President Calvin Coolidge Declaring National Monument, October 15, 1924: Fort Marion, Fort Matanzas / 102 iii B: Executive Order No. 6228: National Monuments to Be Administered by the National Park Service, July 28, 1933 / 101 C: Name Change: Fort Marion to Castillo de San Marcos, June 5, 1942 / 107 D: License to St. -

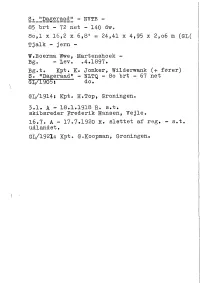

85 Brt - 72 Net - 140 Dw

S^o^^Dageraad*^ - WVTB - 85 brt - 72 net - 140 dw. 8o,l x 16,2 x 6,8' = 24,41 x 4,95 x 2,o6 m (GL( Tjalk - jern - W.Boerma Wwe, Martenshoek - Bg. - lev. .4.1897. Bg.t. Kpt. Ko Jonker, Wilderwank (+ fører) S. "Dageraad" - NLTQ - 8o brt - 67 net GI/1905: do. GL/1914: KptO H.Top, Groningen. 3.1. A - 18.1.1918 R. s.t. skibsreder Frederik Hansen, Vejle, 16.7. A - 17.7.1920 R. slettet af reg. - s.t. udlandet. Gl/1921: Kpt. G.Koopman, Groningen. ^Dagmar^ - HBKN - , 187,81 hrt - 181/173 NRT - E.C. Christiansen, Flenshurg - 1856, omhg. Marstal 1871. ex "Alma" af Marstal - Flb.l876$ C.C.Black, Marstal. 17.2.1896: s.t. Island - SDagmarS - NLJV - 292,99 brt - 282 net - lo2,9 x 26,1 x 14,1 (KM) Bark/Brig - eg og fyr - 1 dæk - hækbg. med fladt spejl - middelf. bov med glat stævn. Bg. Fiume - 1848 - BV/1874: G. Mariani & Co., Fiume: "Fidente" - 297 R.T. 29.8.1873 anrn. s.t. partrederi, Nyborg - "DagmarS - Frcs. 4o.5oo mægler Hans Friis (Møller) - BR 4/24, konsul H.W. Clausen - BR fra 1875 6/24 købm. CF. Sørensen 4/24 " Martin Jensen 4/24 skf. C.J. Bøye 3/24 skf. B.A. Børresen - alle Nyborg - 3/24 29.12.1879: Forlist p.r. North Shields - Tuborg havn med kul - Sunket i Kattegat ca. 6 mil SV for Kråkan, da skibet ramtes af brådsø, der knækkede alle støtter, ramponerede skibets ene side, knuste båden og ødelagde pumperne. -

Published by a Cc Art Books 2020 a C C Ar T Books

PUBLISHED BY ACC ART BOOKS 2020 ACC ART BOOKS PUBLISHED BY ACC ART BOOKS 2020 • Iconic portraits and contact sheets from Goldfinger, Diamonds are Forever, Live and Let Die, Golden Eye and the Bond spoof, Casino Royale • Contributions from actors including George Lazenby and Jane Seymour • Includes a foreword by Robert Wade and Neal Purvis, screenwriters for the latest Bond film, No Time to Die Bond Photographed by Terry O’Neill The Definitive Collection James Clarke Terry O’Neill was given his first chance to photograph Sean Connery as James Bond in the film Goldfinger. From that moment, O’Neill’s association with Bond was made: an enduring legacy that has carried through to the era of Daniel Craig. It was O’Neill who captured gritty and roguish pictures of Connery on set, and it was O’Neill who framed the super-suave Roger Moore in Live and Let Die. His images of Honor Blackman as Pussy Galore are also important, celebrating the vital role of women in the James Bond world. But it is Terry O’Neill’s casual, on- set photographs of a mischievous Connery walking around the casinos of Las Vegas or Roger Moore dancing on a bed with co-star Madeline Smith that show the other side of the world’s most recognisable spy. Terry O’Neill opens his archive to give readers - and viewers - the chance to enter the dazzling world of James Bond. Lavish colour and black and white images are complemented by insights from O’Neill, alongside a series of original essays on the world of James Bond by BAFTA-longlisted film writer, James Clarke; and newly-conducted interviews with a number of actors featured in O’Neill’s photographs. -

Archeological Overview and Assessment Bunker Hill Monument

ARCHEOLOGICAL OVERVIEW AND ASSESSMENT BUNKER HILL MONUMENT Charlestown, Massachusetts Kristen Heitert Submitted to: Northeast Region Archeology Program National Park Service 115 John Street Lowell, Massachusetts 01852 Submitted by: PAL 210 Lonsdale Avenue Pawtucket, Rhode Island 02860 PAL Report No. 2141 January 2009 PAL PUBLICATIONS CARTOGRAPHERS DANA M. RICHARDI/TIM WALLACE GIS SPECIALIST TIM WALLACE GRAPHIC DESIGN/PAGE LAYOUT SPECIALISTS ALYTHEIA M. LAUGHLIN/GAIL M. VAN DYKE EDITOR KEN ALBER TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................1 Site Summary...................................................................................................................1 Scope and Authority .........................................................................................................3 Project Methodology ........................................................................................................3 Consultation ........................................................................................................................4 Archival Research ...............................................................................................................4 Pre- and Post-Contact Cultural Context Development........................................................6 Research and Evaluation of Previous Studies and Collections ...........................................6 Recommendations for Future Research...............................................................................7 -

Oversigt Over Tildelinger (Pdf)

STATENS KUNSTFONDS 2016 ÅRSBERETNING OVERSIGT OVER TILDELINGER TILDELINGER OVERSIGT OVER ALLE TILDELINGER INDHOLD 2 HÆDERSYDELSER 3 OVERSIGT ARKITEKTUR 4 BILLEDKUNST 9 OVER ALLE FILM 47 KUNSTHÅNDVÆRK & DESIGN 50 TILDELINGER LITTERATUR 61 MUSIK 111 I 2016 SCENEKUNST 159 TVÆRGÅENDE UDVALG 183 Note: Oversigten indeholder tildelinger af tilskud, som udvalge- ne har truffet beslutning om i 2016. Nogle af beslutningerne bli- ver bevillingsmæssigt først udmøntet i 2017, og der kan derfor forekomme uoverensstemmelser mellem summerne af de for- skellige tildelinger set i forhold til tilskudsregnskabet i indevæ- rende beretning, idet sidstnævnte udelukkende viser fordelingen af de bevillinger, som udvalgene rådede over i kalenderåret 2016. TILDELINGER TILDELINGER HÆDERSYDELSER 3 Følgende kunstnere er i 2016 tildelt Statens Kunstfonds hædersydelse af repræsentantskabet efter indstilling TILDELINGER fra det relevante legatudvalg i fonden: AF BILLEDKUNST HENRIK OLESEN, billedkunstner HÆDERS- JENS HAANING, billedkunstner KIRSTEN DUFOUR, billedkunstner YDELSER FILM BILLE AUGUST, filminstruktør I 2016 JANNIK HASTRUP, filminstruktør KUNSTHÅNDVÆRK OG DESIGN JAN MACHENHAUER, beklædningsdesigner KAREN BENNICKE, keramiker PER MOLLERUP, designer LITTERATUR HENNING VANGSGAARD, oversætter KATRINE MARIE GULDAGER, forfatter MUSIK IRENE BECKER, komponist JØRGEN EMBORG, komponist STEFFEN BRANDT, sangskriver/komponist HÆDELSEYDELSER TILDELINGER ARKITEKTUR INDHOLD 4 TILDELINGER LEGAT- & PROJEKTSTØTTEUDVALGET OVERSIGT FOR ARKITEKTUR PROJEKTSTØTTE 5 OVER CAN LIS 6 TREÅRIGE -

Dark As a Dungeon: the Rise and Fall of Coal Miners' Nystagmus

SPECIAL ARTICLE Dark as a Dungeon The Rise and Fall of Coal Miners’ Nystagmus Ronald S. Fishman, MD oal miners’ nystagmus was one of the first occupational illnesses ever recognized as being due to a hazardous working environment. It aroused great concern and much controversy in Great Britain in the first half of the 20th century but was not seen in the United States. Miners’ nystagmus became a significant financial problem for the CBritish workmen’s compensation program, and the British medical literature became a forum for speculation as to the nature of the condition. Although new cases of miners’ nystagmus were rare after World War II, the condition continued to be discussed in textbooks through the 1970s, after which it abruptly disappeared without any authoritative summing-up, and thereby hangs a tale. MINERS’ NYSTAGMUS IN tion of miners’ nystagmus appears, in NEURO-OPHTHALMIC TEXTBOOKS Cogan’s typical style—concise, clear, confident: The authoritative chapter on nystagmus, Miners’ nystagmus is...apendular nystag- written by Dell’Osso and Daroff in Glaser’s mus, an exceptionally fine and rapid one, oc- text Neuro-ophthalmology in 1999, lists curring in persons who work in poorly lighted 46 types of nystagmus in 3 columns oc- mines for long periods of time. It is much less cupying an entire page.1 Halfway down the frequent now that mines are better illumi- center column there is a listing called “min- nated. The nystagmus is accompanied by an im- pairment of vision that varies according to the er’s” with a subset called “occupational.” degree of nystagmus and occasionally by an A dagger leads the reader to a footnote illusory movement of the environment... -

The Blitz - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

The Blitz - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Blitz From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Blitz (shortened from German 'Blitzkrieg', "lightning war") was the period of sustained strategic bombing of the The Blitz United Kingdom by Nazi Germany during the Second World Part of Second World War, Home Front War. Between 7 September 1940 and 21 May 1941 there were major aerial raids (attacks in which more than 100 tonnes of high explosives were dropped) on 16 British cities. Over a period of 267 days (almost 37 weeks), London was attacked 71 times, Birmingham, Liverpool and Plymouth eight times, Bristol six, Glasgow five, Southampton four, Portsmouth and Hull three, and there was also at least one large raid on another eight cities.[1] This was a result of a rapid escalation starting on 24 August 1940, when night bombers aiming for RAF airfields drifted off course and accidentally destroyed several London homes, killing civilians, combined with the UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill's immediate response The undamaged St Paul's Cathedral surrounded by smoke of bombing Berlin on the following night. and bombed-out buildings in December 1940 in the iconic St Paul's Survives photo Starting on 7 September 1940, London was bombed by the Date 7 September 1940 – 21 May 1941[1][a] [7] Luftwaffe for 57 consecutive nights. More than one (8 months, 1 week and 2 days) million London houses were destroyed or damaged, and more than 40,000 civilians were killed, almost half of them Location United Kingdom in London.[4] Ports and industrial centres outside London Result German strategic failure[3] were also heavily attacked.