Occurrences and Denotation of the Italian Lexical Type Pizza

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chanukah Cooking with Chef Michael Solomonov of the World

Non-Profit Org. U.S. POSTAGE PAID Pittsfield, MA Berkshire Permit No. 19 JEWISHA publication of the Jewish Federation of the Berkshires, serving V the Berkshires and surrounding ICE NY, CT and VT Vol. 28, No. 9 Kislev/Tevet 5781 November 23 to December 31, 2020 jewishberkshires.org Chanukah Cooking with Chef The Gifts of Chanukah Michael Solomonov of the May being more in each other’s presence be among World-Famous Restaurant Zahav our holiday presents On Wednesday, December 2 at 8 p.m., join Michael Solomonov, execu- tive chef and co-owner of Zahav – 2019 James Beard Foundation award winner for Outstanding Restaurant – to learn to make Apple Shrub, Abe Fisher’s Potato Latkes, Roman Artichokes with Arugula and Olive Oil, Poached Salmon, and Sfenj with Cinnamon and Sugar. Register for this live virtual event at www.tinyurl.com/FedCooks. The event link, password, recipes, and ingredient list will be sent before the event. Chef Michael Solomonov was born in G’nai Yehuda, Israel, and raised in Pittsburgh. At the age of 18, he returned to Israel with no Hebrew language skills, taking the only job he could get – working in a bakery – and his culinary career was born. Chef Solomonov is a beloved cham- pion of Israel’s extraordinarily diverse and vibrant culinary landscape. Chef Michael Solomonov Along with Zahav in Philadelphia, Solomonov’s village of restaurants include Federal Donuts, Dizengoff, Abe Inside Fisher, and Goldie. In July of 2019, Solomonov brought BJV Voluntary Subscriptions at an another significant slice of Israeli food All-Time High! .............................................2 culture to Philadelphia with K’Far, an Distanced Holidays? Been There, Israeli bakery and café. -

Tradizione Culinaria

Tradizione Culinaria in Val di Lima Agriturismo IL LAGO Tradizione Culinaria Prima di lasciarvi alla degustazione delle ricette che seguiranno, vorrei esprimere un particolare ringraziamento alle donne che con tanto amore e pazienza mi hanno accolto e fatto partecipe della loro giovinezza, trasmettendomi sensazioni così vivide che ora sembra di aver vissuto e visto con i miei occhi quei tempi, assaporando odori e sapori che con tanta maestria mi hanno descritto. Vorrei anche ricordare i loro nomi: Gemma, Nilda, Sabina, e due cari “nonni” che ora non sono più tra noi, Dina e Attilio, che per primi ci hanno accolti come figli facendoci conoscere ed apprezzare le bellezze di questi luoghi. Infine un ringraziamento agli amici di Livorno che con me hanno accettato la scommessa di una vita vissuta nel rispetto della natura e dell’uomo, alla ricerca della memoria e dell’essenza della libertà, per un futuro migliore. Maria Annunziata Bizzarri Agrilago Azienda Agricola - Agrituristica IL LAGO via di Castello - Casoli Val di Lima 55022 Bagni di Lucca (LU) tel. 0583.809358 fax 0583.809330 Cell. 335.1027825 www.agrilago.it [email protected] Testi tratti da una ricerca di: Maria Annunziata Bizzarri 1 Tradizione Culinaria UN PO’ DI STORIA A Casoli, nella ridente Val di Lima, ogni famiglia aveva un metato che poteva far parte della casa o essere nelle immediate vicinanze o nella selva. Nel metato venivano seccate le castagne che avrebbero costituito il sostentamento per l’intero anno e rappresentato una merce di scambio per l’acquisto dei generi alimentari non prodotti direttamente, come il sale e lo zucchero. -

Catering Menu

Catering (Collection only) Minimum order £100 Deluxe falafel platter £115 mezze-salads, dips platter £115 40 Large homemade falafel balls, Israeli Feeds 6 - 8 Hummus, tzatziki, Israeli salad, Tabouli Feeds 6 - 8 salad, hummus, Tabouli salad, Tangy People salad, aubergine & pine nuts salad, People cabbage slaw, pickles & shifka peppers, pickles, olives & shifka peppers, chilli Chilli harissa sauce, tahini sauce harissa sauce, Israeli pita(5), greek & Israeli pita(10) pita(5) Allergens: Cereals(gluten), sesame, soy Allergens: Cereals(gluten), sesame, soy, milk, nuts Extras: Extras: Homemade coleslaw + £15 With tangy cabbage slaw + £15 Char-grilled aubergine & tahini + £30 Char-grilled aubergine & tahini + £30 With homemade tzatziki + £15 With homemade tzatziki + £15 Falafel bar £12 pP Israeli tasting menu £26 pp 15 Person minimum order 15 Person minimum order 4 Large falafel balls per person Falafel bar or mezze platter menu Israeli salad, hummus, Tabouli salad, Tangy + Homemade chicken shawarma cabbage slaw, pickles & shifka peppers, + Chicken shashlik (skewers of chicken thigh/breast) chilli harissa sauce, tahini sauce & + Amba sauce Israeli pita(1 pita per person) + Extra pita PP (Kosher meat available on request at extra cost) Allergens: Cereals(gluten), sesame, soy, milk Allergens: Cereals(gluten), sesame, soy, milk, nuts, celery Extras: With tangy cabbage slaw + £2.00 per person Meat dishes served in aluminium foil containers to be reheated on site With homemade tzatziki + £2.00 per person Extras: Homemade coleslaw + £2.00 per person Other options may be available on request With homemade tzatziki + £2.00 per person Box of falafel balls £20 box of smoky cauliflower £30 box of grilled AUBERGINE £30 25 Homemade large falafel balls, BBQ cauliflower with fresh turmeric, tahini, Char-grilled aubergine with garlic, served with tahini sumac, garlic & herbs oil & squeeze of lemon tahini, harissa oil, pine nuts, fresh green herbs & Zahatar. -

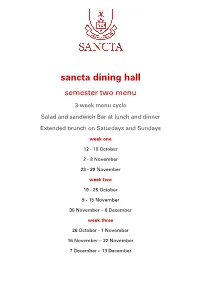

Sancta Dining Hall Semester Two Menu

sancta dining hall semester two menu 3-week menu cycle Salad and sandwich Bar at lunch and dinner Extended brunch on Saturdays and Sundays week one 12 - 18 October 2 - 8 November 23 - 29 November week two 19 - 25 October 9 - 15 November 30 November – 6 December week three 26 October - 1 November 16 November – 22 November 7 December – 13 December week one menu week one menu dates 12 - 18 October 2 - 8 November 23 - 29 November VG = Vegan V= Vegetarian GF = Gluten-free DF = Dairy-free WEEK ONE – MONDAY LUNCH Country NSW Kitchen theme Herb roasted chicken thighs DF GF Kidney Bean and Quinoa Balls VG GF DF Brown Rice with mushroom and garlic DF GF "Superfood Salad", Kale, Spinach, Peas, Grains & Seeds GF DF Roasted broccolini, paprika roasted cauliflower DF GF Tahini Salad Dressing, Soy Salad Dressing, Fresh Lemon wedges, Tartare Sauce, Herb Aioli, Tomato Sugo DINNER Roast Dinner Theme Roast Beef (gravy optional) DF GF Spiced Baked Lentil and Veggie Burgers VG GF DF White Potato Mash VG GF DF Minted Peas / Steamed Brussel Sprouts / Herb roasted vegetables: pumpkin, eggplant, capsicum / Cauliflower Bake Coconut Yoghurt with Fruit and Berries DF + Daily Gourmet Salad and Sandwich Bar + WEEK ONE - TUESDAY LUNCH Summer theme Mango chicken breast (chicken breast diced, cooked in mango slices and olive oil) DF GF Chickpea and Spinach Falafels GF DF Steamed Jasmine Rice GF DF Mixed Leaf Salad with mango slices GF DF DINNER (excludes 13 October Formal Dinner) Israeli theme 8-hour Slow Cooked Lamb Shoulder GF DF Chickpea Falafel VG, GF, DF Cinnamon -

Vin En Amphore Coups De Cœur Vins Oranges

VIN EN AMPHORE COUPS DE CŒUR ❤ VINS ORANGES � VINS AU VERRE (cl.10) BOLLICINE Champagne BdB Grand Cru Cramant, D.Grellet CHAMPAGNE CHF 18 Prosecco, Casa Coste Piane VENETO CHF 9 VINI BIANCHI Pinot Grigio, Meran ALTO ADIGE 2019 CHF 9 Trebbiano, Edoardo Sderci TOSCANA 2019 CHF 8 Fiano Irpinia, Picariello CAMPANIA 2018 CHF 10 Chardonnay Lices en Peria, Aigle 2 têtes JURA 2015 CHF 10 Rosé Maggese, TOSCANA 2019 CHF 8 VINS DE MACERATION ET ORANGES Malvasia, Le Nuvole BASILICATA 2018 CHF 10 Bianco alla Marta, Buondonno � TOSCANA 2017 CHF 7 VINI ROSSI Nero D’Avola Turi, Salvatore Marino SICILIA 2019 CHF 8 Sangiovese La Gioia, Riecine TOSCANA 2014 CHF 13 Cabernet Riserva, Renato Keber FRIULI 2010 CHF 12 Barbera/Dolcetto Onde Gr., Fabio Gea PIEMONTE 2017 CHF 14 Barolo, Casina Bric PIEMONTE 2013 CHF 16 VINI DESSERT (cl.6) Moscato di Noto, Marabino SICILIA 2016 CHF 10 VINS D’EXCEPTION AU VERRE CORAVIN (cl.10) VINI BIANCHI Friulano Riserva,RENATO KEBER FRIULI 2005 CHF 15 Pinot Bianco, RENATO KEBER FRIULI 2004 CHF 19 Chardonnay Riserva, RENATO KEBER FRIULI 2003 CHF 20 Verdicchio Riserva Il San Lorenzo MARCHE 2004 CHF 26 VINI ROSSI Langhe Rosso, San Fereolo PIEMONTE 2006 CHF 15 Testamatta, Bibi Graetz 98 Pt. RP JS TOSCANA 2013 CHF 35 Chianti Classico GRAN SELEZIONE, Candialle TOSCANA 2013 CHF 23 Amarone, Monte dei Ragni VENETO 2012 CHF 35 Merlot Tresette, Riecine TOSCANA 2016 CHF 20 CHAMPAGNE 2/3 CEPAGES LE MONT BENOIT EMMANUEL BROCHET CHF 140 3C TROIS CEPAGES BOURGEOIS DIAZ CHF 120 CUVEE « N » BOURGEOIS DIAZ CHF 130 CHAMPAGNE CHARDONNAY BLANC D’ARGILLE -

View Paprika & Colbeh Full Menu

Catering for All Occasions | Gift Certificates Available FOR PICKUP & DELIVERY SCAN HERE TO ORDER ONLINE 32 W 39th Street New York, New York OU Certified (212) 354-8181 (212) 679-1100 www.colbeh.com www.paprikacater.com @colbencaterer @paprikakosher גלאט כשר OU Certified Download the app: Colbeh & Paprika Kosher HUMMUS PLATES SANDWICHES Choose A Bread: Served with Pickles $9.50 hummus falafel (gf,v) $13.50 original hummus (gf,v) *lafa $2 $13.50 Hummus Plate with Falafel Balls, Tahini, sabich *white baguette $2 *white wrap Eggplant, Hard Boiled Egg, Pickles, Tahini, and Pita hummus shawarma (gf) $17.50 *whole wheat wrap *white pita Harisa, and Amba Hummus Plate with Chicken Shawarma falafel (v) $9.50 shawarma $16.50 and Pita With Hummus, Cabbage Salad, Pickles APPETIZERS Hummus, Israeli Salad, Pickles, and Tahini $16.50 $17.50 soup of the day $9.50 french fries $8.50 malawach roll (v) pap burger Hard Boiled Egg, Israeli Salad, Hummus, 8oz. Juicy Beef Burger, Tomatoes, Lettuce, cauliflower over tahini $9.50 duck taco $14.50 Schug, Wrapped in a Yeminite Puff Pastry Pickles, Avocado, Garlic Aioli, Served on a (gf,v) Served with Enoki Mushrooms, Daikon Bread *add chicken $8.50 Bun Warm Cauliflower with Pine Nuts, Mint, and Radish in a Sweet Potato Shell Topped with $18.50 $18.50 Parsley over Tahini Scallions koobideh sandwich white koobideh sandwich Ground Beef Sandwich Ground Chicken Breast Sandwich arays $18.50 $14.50 shakshuka (gf,v) $13.50 Grilled Kebab Stuffed in a Pita to 3 Poached Eggs in a Tomato Stew and impossible burger (v) $17.50 cauliflower shawarma Perfection. -

Soul Stirring in Israel, There’S an Immigrant Behind Almost Every Stove

gourmet travels SouL Stirring in israel, there’s an immigrant behind almost every stove. the Yemenite Jews of tel Aviv are particularly creative. bY AdeenA SussmAn TIR HARDER!” said Ilana Tzana’ani, hovering over me in her kitchen in Rosh Ha’Ayin, a city near Tel Aviv that’s a center of Israel’s Yemenite-Jewish immi- Sgrant community. “We haven’t got the thickness we w ant yet.” I sat on a low stool rotating a wooden paddle in- side a large aluminum stockpot wedged between my knees. My shoulders had begun to ache, and I could feel the hint of a blister forming on the inside of my right palm. Ilana and her sister-in-law, Daphna Sa’ad, lent encouragement as the semolina-and-water mixture in the pot congealed into asid, a thick porridge meant to accompany a soup—this one a sim- ple pot of chicken, potatoes, and vegetables with Yemenite spices—that was simmering on the stove. “You remember what asid means, right?” Ilana laughed. “Cement.” R In Yemenite-Jewish tradition, chicken soup becomes a feast. ineau S tyling:ruth cou S food S romuloyane 186 g o u r m e t d e c e m B e r 2 0 0 7 gourmet travels In Yemen, where the Jews—everyone, in fact—lived in In Israel—where practically every kitchen has an immigrant poverty for thousands of years, flour equaled food. -

Sweet Chestnut

Sweet chestnut There are four main species of chestnuts; the Japanese chestnut (Castanea crenata), the Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima), the American chestnut (Castanea dentata), and the European chestnut (Castanea sativa). There are a considerable number of cultivars each with specific characteristics. The European chestnut, also named sweet chestnut, is a large growing tree reaching a height of 35 meters with a wide spreading canopy. It is a tree of great longevity. Beside the parish church of Totworth in Gloucestershire is a sweet chestnut tree, some may say it's more like a mini woodland than a tree as many of the branches have rooted and it is hard to see where the original trunk ends and the new trunks begin. The main trunk could be 1,100 years old making it one of the oldest trees in the country. The sweet chestnut is a deciduous tree with tongue shaped leaves that grow to about 25cm long and have sharply pointed widely spaced teeth. The flowers appear in late spring or early summer with male and female flowers borne on every tree, however as the flowering times generally do not overlap one tree by itself won't have a crop of nuts, more than one type of tree is needed. They are mainly wind pollinated though bees also pollinate the flowers and chestnut honey is a speciality in certain regions of France & Italy. The nuts develop in spiky cases with between 1 – 3 glossy chestnuts in each. Mature nuts are ready to harvest in October. Sweet chestnut cultivation Sweet chestnuts thrive best on deep, sandy loams they will not flourish in wet heavy clay. -

My Iranian Sukkah

My Iranian Sukkah FARIDEH DAYANIM GOLDIN Every year after Yom Kippur, my husband Norman and I try to bring together the pieces of our sukkah, our temporary home for a week, a reminder of our frailty as Jews. Every year we wonder where we had last stored the metal frame, the bamboo roof, and the decorations. Every year we wonder about the weather. Will we have to dodge the raindrops and the wind once again this year for a quick bracha before eating inside? Will our sukkah stand up? Will there be a hurricane? I insisted on building a sukkah the fi rst time we had a yard. My husband protested that it would never last in Portsmouth, Virginia, remembering the sukkahs of his childhood and youth in that town, when his father, Milton, struggled to balance the wobbly structure in the more protected area outside the living room. Every year, my father-in-law had to bring it down in the middle of the holiday, fear- ing that strong winds from one hurricane or another would topple the sukkah against the building, bringing down bricks, glass, and the roof shingles. In Iran of my youth, we had no such worries. Every year, a month before the holiday, my father ordered four young trees from the town’s wood supplier. He made sure they were cut to the exact height and had the two largest branches trimmed in a V, like two hands ready to catch a ball. Nails and screws being forbidden in My Iranian Sukkah ❖ 225 Copyright © 2009. -

Parking Garage Gives Way to New Stapleton Neighborhood

Distributed to the Stapleton, Park Hill, Lowry, Montclair, Mayfair, Hale and East Colfax neighborhoods DENVER, COLORADO FEBRUARY 2011 Parking Garage Gives Way to New Stapleton Neighborhood In the demolition of the parking garage from the old Stapleton airport, 100,000 tons of con - travel only a short distance to deposit their loads, which reduces the amount of gas used and limits crete are being taken to the northern edge of Stapleton where it is being recycled—and much the wear and tear of 20-ton trucks on public roadways. The concrete is being separated from the of it is likely to be re-used in upcoming construction at Stapleton. That’s 5,000 truckloads that steel, which is sent to a scrap yard. Ninety-eight percent of what’s torn down will be recycled. By Carol Roberts the technical requirements of safely tearing down 100,000 tons of concrete in a populated area. rivers passing the old parking garage on Martin Luther King just west of Central First the project had to be abated, says Rick Givan, Senior Executive Vice President of Recycled Park Blvd. can see that the structure is gradually disappearing—but few would Materials Co., Inc. “You have a national abatement firm in there going over every single inch of Dguess the efficiency of the recycling efforts going on there or stop to think about the garage making sure there’s nothing left prior to its demolition. It was (continued on page 12) A Closer Look at the Job of the Denver Mayor Recent Grads Look Back Denver’s City Attorney on High School.. -

Regione Abruzzo

20-6-2014 Supplemento ordinario n. 48 alla GAZZETTA UFFICIALE Serie generale - n. 141 A LLEGATO REGIONE ABRUZZO Tipologia N° Prodotto 1 centerba o cianterba liquore a base di gentiana lutea l., amaro di genziana, 2 digestivo di genziana Bevande analcoliche, 3 liquore allo zafferano distillati e liquori 4 mosto cotto 5 ponce, punce, punk 6 ratafia - rattafia 7 vino cotto - vin cuott - vin cott 8 annoia 9 arrosticini 10 capra alla neretese 11 coppa di testa, la coppa 12 guanciale amatriciano 13 lonza, capelomme 14 micischia, vilischia, vicicchia, mucischia 15 mortadella di campotosto, coglioni di mulo 16 nnuje teramane 17 porchetta abruzzese 18 prosciuttello salame abruzzese, salame nostrano, salame artigianale, Carni (e frattaglie) 19 salame tradizionale, salame tipico fresche e loro 20 salame aquila preparazione 21 salamelle di fegato al vino cotto 22 salsiccia di fegato 23 salsiccia di fegato con miele 24 salsiccia di maiale sott’olio 25 salsicciotto di pennapiedimonte 26 salsicciotto frentano, salsicciotto, saiggicciott, sauccicciott 27 soppressata, salame pressato, schiacciata, salame aquila 28 tacchino alla canzanese 29 tacchino alla neretese 30 ventricina teramana ventricina vastese, del vastese, vescica, ventricina di guilmi, 31 muletta 32 cacio di vacca bianca, caciotta di vacca 33 caciocavallo abruzzese 34 caciofiore aquilano 35 caciotta vaccina frentana, formaggio di vacca, casce d' vacc 36 caprino abruzzese, formaggi caprini abruzzesi 37 formaggi e ricotta di stazzo 38 giuncata vaccina abruzzese, sprisciocca Formaggi 39 giuncatella -

Jewish Bserver Vol

the Jewish bserver www.jewishobservernashville.org Vol. 82 No. 5 • May 2017 5 Iyyar-6 Sivan 5777 Chef Joe will be manning the grill as community Yom Ha’atzmaut celebration returns to Red Caboose Park oe Perlen has cooked the food for a lot of community events What: Free community over the years – fundraisers and celebration of Yom Purim carnivals at Akiva School, Ha’atzmaut, Israeli BBYO’s annual Pasta before Independence Day Passover party. J“At Akiva they call me Chef Joe,” When: 3-6 p.m., Sunday, he says. “I know how to cook for a whole May 7 bunch of people,” On Sunday, May 7, Chef Joe will be Where: Red Caboose Park, cooking for one of the Nashville Jewish The popular New York-based trio Jonathan Rimberg and Friends, show here at the 694 Colice Jeanne Road community’s largest gatherings – the 2016 Yom Ha’atzmaut celebration in Red Caboose Park, will again provide the musical entertainment at this month’s celebration of Israel’s independence day. (Photo by Rick Malkin) Contact: Adi Ben Dor at annual celebration of Yom Ha’atzmaut, Israel’s Independence Day, sponsored it will move indoors at the GJCC.) has been organizing the celebration. [email protected] by Jewish Federation of Nashville and Returning to provide the musical The Nashville Israeli folk dance group Middle Tennessee in conjunction with entertainment this year will be a three- will be on hand to lead traditional kosher hot dogs and will also provide typ- the Gordon Jewish Community Center man band led by Jonathan Rimberg, a and contemporary Israeli dancing, she ical Israeli fare like falafel, pita and salad.