SPF China Observer China Observer Project Web Collection (March to August 2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Connections a Triannual E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations

Comparative Connections A Triannual E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations China-Russia Relations: Navigating through the Ukraine Storm Yu Bin Wittenberg University Against the backdrop of escalating violence in Ukraine, Sino-Russian relations were on the fast track over the past four months in three broad areas: strategic coordination, economics, and mil- mil relations. This was particularly evident during President Putin’s state visit to China in late May when the two countries inked a 30-year, $400 billion gas deal after 20 years of hard negotiation. Meanwhile, the two navies were drilling off the East China Sea coast and the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA) was being held in Shanghai. Beyond this, Moscow and Beijing were instrumental in pushing the creation of the $50 billion BRICS development bank and a $100 billion reserve fund after years of frustrated waiting for a bigger voice for the developing world in the IMF and World Bank. Putin in Shanghai for state visit and more President Vladimir Putin traveled to Shanghai on May 20-21 to meet Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping. This was the seventh time they have met since March 2013 when Xi assumed the presidency in China. The trip was made against a backdrop of a deepening crisis in Ukraine: 42 pro-Russian activists were killed in the Odessa fire on May 2 and pro-Russian separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk declared independence on May 11. Four days after Putin’s China trip, the Ukrainian Army unveiled its “anti-terrorist operations,” and on July 17 Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 was downed. -

China Data Supplement

China Data Supplement October 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 29 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 36 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 45 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR................................................................................................................ 54 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR....................................................................................................................... 61 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 66 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

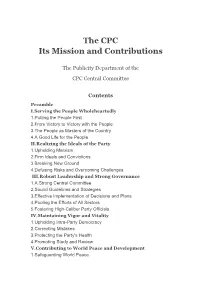

The CPC Its Mission and Contributions

The CPC Its Mission and Contributions The Publicity Department of the CPC Central Committee Contents Preamble I.Serving the People Wholeheartedly 1.Putting the People First 2.From Victory to Victory with the People 3.The People as Masters of the Country 4.A Good Life for the People II.Realizing the Ideals of the Party 1.Upholding Marxism 2.Firm Ideals and Convictions 3.Breaking New Ground 4.Defusing Risks and Overcoming Challenges III.Robust Leadership and Strong Governance 1.A Strong Central Committee 2.Sound Guidelines and Strategies 3.Effective Implementation of Decisions and Plans 4.Pooling the Efforts of All Sectors 5.Fostering High-Caliber Party Officials IV.Maintaining Vigor and Vitality 1.Upholding Intra-Party Democracy 2.Correcting Mistakes 3.Protecting the Party's Health 4.Promoting Study and Review V.Contributing to World Peace and Development 1.Safeguarding World Peace 2.Pursuing Common Development 3.Following the Path of Peaceful Development 4.Building a Global Community of Shared Future Conclusion Preamble The Communist Party of China (CPC), founded in 1921, has just celebrated its centenary. These hundred years have been a period of dramatic change – enormous productive forces unleashed, social transformation unprecedented in scale, and huge advances in human civilization. On the other hand, humanity has been afflicted by devastating wars and suffering. These hundred years have also witnessed profound and transformative change in China. And it is the CPC that has made this change possible. The Chinese nation is a great nation. With a history dating back more than 5,000 years, China has made an indelible contribution to human civilization. -

Xi Jinping's War on Corruption

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2015 The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption Harriet E. Fisher University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Harriet E., "The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption" (2015). Honors Theses. 375. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/375 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping’s War on Corruption By Harriet E. Fisher A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies and the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2015 Approved by: ______________________________ Advisor: Dr. Gang Guo ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Peter K. Frost i © 2015 Harriet E. Fisher ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii For Mom and Pop, who taught me to learn, and Helen, who taught me to teach. iii Acknowledgements I am indebted to a great many people for the completion of this thesis. First, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Gang Guo, for all his guidance during the thesis- writing process. His expertise in China and its endemic political corruption were invaluable, and without him, I would not have had a topic, much less been able to complete a thesis. -

Tiktok and Wechat Curating and Controlling Global Information Flows

TikTok and WeChat Curating and controlling global information flows Fergus Ryan, Audrey Fritz and Daria Impiombato Policy Brief Report No. 37/2020 About the authors Fergus Ryan is an Analyst working with the International Cyber Policy Centre at ASPI. Audrey Fritz is a Researcher working with the International Cyber Policy Centre at ASPI. Daria Impiombato is an Intern working with the International Cyber Policy Centre at ASPI. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Danielle Cave and Fergus Hanson for their work on this project. We would also like to thank Michael Shoebridge, Dr Samantha Hoffman, Jordan Schneider, Elliott Zaagman and Greg Walton for their feedback on this report as well as Ed Moore for his invaluable help and advice. We would also like to thank anonymous technically-focused peer reviewers. This project began in 2019 and in early 2020 ASPI was awarded a research grant from the US State Department for US$250k, which was used towards this report. The work of ICPC would not be possible without the financial support of our partners and sponsors across governments, industry and civil society. What is ASPI? The Australian Strategic Policy Institute was formed in 2001 as an independent, non-partisan think tank. Its core aim is to provide the Australian Government with fresh ideas on Australia’s defence, security and strategic policy choices. ASPI is responsible for informing the public on a range of strategic issues, generating new thinking for government and harnessing strategic thinking internationally. ASPI’s sources of funding are identified in our Annual Report, online at www.aspi.org.au and in the acknowledgements section of individual publications. -

Winter 2019 Full Issue the .SU

Naval War College Review Volume 72 Article 1 Number 1 Winter 2019 2019 Winter 2019 Full Issue The .SU . Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Naval War College, The .SU . (2019) "Winter 2019 Full Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 72 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol72/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naval War College: Winter 2019 Full Issue Winter 2019 Volume 72, Number 1 Winter 2019 Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2019 1 Naval War College Review, Vol. 72 [2019], No. 1, Art. 1 Cover Aerial view of an international container cargo ship. In “Ships of State?,” Christopher R. O’Dea describes how China COSCO Shipping Corporation Limited has come to control a rapidly expanding network of ports and terminals, ostensibly for commercial purposes, but has thereby gained the ability to project power through the increased physical presence of its naval vessels—turning the oceans that historically have protected the United States from foreign threats into a venue in which China can challenge U.S. interests. Credit: Getty Images https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol72/iss1/1 2 Naval War College: Winter 2019 Full Issue NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REVIEW Winter 2019 Volume 72, Number 1 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE PRESS 686 Cushing Road Newport, RI 02841-1207 Published by U.S. -

Indo-Pacific

INDO-PACIFIC Chinese Central Military Commission Issues New Outline of Joint Operations OE Watch Commentary: China’s Central Military Commission (CMC) has issued an outline for improving the joint combat capabilities of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The CMC is China’s senior military authority. According to a press release regarding the outline (which itself is not public) published by state-run press agency Xinhua, the document represents the highest level of the Chinese military’s system of operational regulations and is meant to clarify responsibilities and generally standardize how operations work at higher levels across the PLA. While references to the PLA’s joint operations appeared in white papers in the early 2000s, real progress toward actually reaching that goal has only appeared in the past ten years. At the end of 2015, the CMC reorganized China’s military regions into a system of joint Theater Commands and abolished the General Staff Department in favor of a Joint Staff Department with clearer lines of communication and a less dominant role for PLA ground forces. The 2019 Defense White Paper released by the Chinese State Council previously General Li Zuocheng, chief of the Joint Staff Department of the committed the PLA to “generally achieve mechanization by the year 2020 with Central Military Commission. Source: Chief Petty Officer Elliott Fabrizio via Wikimedia,, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/48/ significantly enhanced informatization and greatly improved strategic capabilities,” China%E2%80%99s_Central_Military_Commission_Gen._Li_Zuocheng.jpg, Public Domain essentially completing modernization by 2035 and “fully transforming” into “world- class forces” by 2050. -

2019 China Military Power Report

OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China ANNUAL REPORT TO CONGRESS Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2019 Office of the Secretary of Defense Preparation of this report cost the Department of Defense a total of approximately $181,000 in Fiscal Years 2018-2019. This includes $12,000 in expenses and $169,000 in DoD labor. Generated on 2019May02 RefID: E-1F4B924 OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2019 A Report to Congress Pursuant to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2000, as Amended Section 1260, “Annual Report on Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, Public Law 115-232, which amends the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2000, Section 1202, Public Law 106-65, provides that the Secretary of Defense shall submit a report “in both classified and unclassified form, on military and security developments involving the People’s Republic of China. The report shall address the current and probable future course of military-technological development of the People’s Liberation Army and the tenets and probable development of Chinese security strategy and military strategy, and of the military organizations and operational concepts supporting such development over the next 20 years. -

Speech at a Ceremony Marking the Centenary of the Communist Party of China July 1, 2021

Speech at a Ceremony Marking the Centenary of the Communist Party of China July 1, 2021 Xi Jinping Comrades and friends, Today, the first of July, is a great and solemn day in the history of both the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Chinese nation. We gather here to join all Party members and Chinese people of all ethnic groups around the country in celebrating the centenary of the Party, looking back on the glorious journey the Party has traveled over 100 years of struggle, and looking ahead to the bright prospects for the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. To begin, let me extend warm congratulations to all Party members on behalf of the CPC Central Committee. On this special occasion, it is my honor to declare on behalf of the Party and the people that through the continued efforts of the whole Party and the entire nation, we have realized the first centenary goal of building a moderately prosperous society in all respects. This means that we have brought about a historic resolution to the problem of absolute poverty in China, and we are now marching in confident strides toward the second centenary goal of building China into a great modern socialist country in all respects. This is a great and glorious accomplishment for the Chinese nation, for the Chinese people, and for the Communist Party of China! Comrades and friends, The Chinese nation is a great nation. With a history of more than 5,000 years, China has made indelible contributions to the progress of human civilization. -

China's Logistics Capabilities for Expeditionary Operations

China’s Logistics Capabilities for Expeditionary Operations The modular transfer system between a Type 054A frigate and a COSCO container ship during China’s first military-civil UNREP. Source: “重大突破!民船为海军水面舰艇实施干货补给 [Breakthrough! Civil Ships Implement Dry Cargo Supply for Naval Surface Ships],” Guancha, November 15, 2019 Primary author: Chad Peltier Supporting analysts: Tate Nurkin and Sean O’Connor Disclaimer: This research report was prepared at the request of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission to support its deliberations. Posting of the report to the Commission's website is intended to promote greater public understanding of the issues addressed by the Commission in its ongoing assessment of U.S.-China economic relations and their implications for U.S. security, as mandated by Public Law 106-398 and Public Law 113-291. However, it does not necessarily imply an endorsement by the Commission or any individual Commissioner of the views or conclusions expressed in this commissioned research report. 1 Contents Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology, Scope, and Study Limitations ........................................................................................................ 6 1. China’s Expeditionary Operations -

China-Taiwan Relations: the Shadow of SARS

China-Taiwan Relations: The Shadow of SARS by David G. Brown Associate Director, Asian Studies The Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies Throughout this quarter, Beijing and Taipei struggled to contain the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). SARS dramatically reduced cross-Strait travel; its effects on cross-Strait economic ties appear less severe but remain to be fully assessed. SARS intensified the battle over Taiwan’s request for observer status at the World Health Organization (WHO). Although the World Health Assembly (WHA) again rejected Taiwan, the real problems of a global health emergency led to the first contacts between the WHO and Taiwan. Beijing’s handling of SARS embittered the atmosphere of cross- Strait relations and created a political issue in Taiwan that President Chen Shui-bian is moving to exploit in next year’s elections. SARS The SARS health emergency dominated cross-Strait developments during this quarter. With the dramatic removal of its health minister and the mayor of Beijing in mid-April, Beijing was forced to admit that it was confronting a health emergency with serious domestic and international implications. For about a month thereafter, Taiwan was proud of its success in controlling SARS. Then its first SARS death and SARS outbreaks in several hospitals led to first Taipei and then all Taiwan being added to the WHO travel advisory list. The PRC and Taiwan each in its own way mobilized resources and launched mass campaigns to control the spread of SARS. By late June, these efforts had achieved considerable success and the WHO travel advisories for both, as well as for Hong Kong, had been lifted. -

The Lions's Share, Act 2. What's Behind China's Anti-Corruption Campaign?

The Lions’s Share, Act 2. What’s Behind China’s Anti-Corruption Campaign? Guilhem Fabre To cite this version: Guilhem Fabre. The Lions’s Share, Act 2. What’s Behind China’s Anti-Corruption Campaign?. 2015. halshs-01143800 HAL Id: halshs-01143800 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01143800 Preprint submitted on 20 Apr 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Séminaire BRICs FMSH - CRBC The Lions’s Share, Act 2. What’s Behind China’s Anti-Corruption Campaign? Guilhem Fabre N°92 | april 2015 As we have seen in a previous working paper ( « The lion’s share : What’s behind China’s economic slowdown ? »), China’s elite have largely benefited from control of state assets and manipulation of the factors market (land, labor and capital) during the first decade of this cen- tury. Along with strong growth and social mobility, the accumulation of wealth has created some of the most flagrant social polarization worldwide, much higher than the official statistics. Instead of taking concrete measures to correct these inequalities, according to the new blueprint of reforms launched by the 3rd Plenum in November 2013, the new direction has focused on a gigantic campaign against corruption.