Winter 2019 Full Issue the .SU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary Justice: the Price of Treason for Eight World War Ii German Prisoners of War

SUMMARY JUSTICE: THE PRICE OF TREASON FOR EIGHT WORLD WAR II GERMAN PRISONERS OF WAR A Thesis by Mark P. Schock Bachelor of Arts, Kansas Newman College, 1978 Submitted to the Department of History and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of Master of Arts May 2011 © Copyright 2011 by Mark P. Schock All Rights Reserved SUMMARY JUSTICE: THE PRICE OF TREASON FOR EIGHT WORLD WAR II GERMAN PRISONERS OF WAR The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommended that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts with a major in History. ___________________________________ Robert Owens, Committee Chair ___________________________________ Robin Henry, Committee Member ___________________________________ William Woods, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To the memory of my father, Richard Schock, and my uncle Pat Bessette, both of whom encouraged in me a deep love of history and country iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank my adviser, Dr. Robert Owens, for his incredible patience with an old dog who had such trouble with new tricks. Special thanks go to Dr. Anthony and Dana Gythiel whose generous grant allowed me to travel to the National Archives and thus gain access to many of the original documents pertinent to this story. I’d also like to thank Colonel Jack Bender, U.S.A.F (ret.), for his insight into the workings of military justice. Special thanks are likewise due to Lowell May, author of two books about German POWs incarcerated in Kansas during World War II. -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 29

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 29 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2003: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2003 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361-4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 CONTENTS BATTLE OF BRITAIN DAY. Address by Dr Alfred Price at the 5 AGM held on 12th June 2002 WHAT WAS THE IMPACT OF THE LUFTWAFFE’S ‘TIP 24 AND RUN’ BOMBING ATTACKS, MARCH 1942-JUNE 1943? A winning British Two Air Forces Award paper by Sqn Ldr Chris Goss SUMMARY OF THE MINUTES OF THE SIXTEENTH 52 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING HELD IN THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CLUB ON 12th JUNE 2002 ON THE GROUND BUT ON THE AIR by Charles Mitchell 55 ST-OMER APPEAL UPDATE by Air Cdre Peter Dye 59 LIFE IN THE SHADOWS by Sqn Ldr Stanley Booker 62 THE MUNICIPAL LIAISON SCHEME by Wg Cdr C G Jefford 76 BOOK REVIEWS. 80 4 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal -

United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922

Cover: During World War I, convoys carried almost two million men to Europe. In this 1920 oil painting “A Fast Convoy” by Burnell Poole, the destroyer USS Allen (DD-66) is shown escorting USS Leviathan (SP-1326). Throughout the course of the war, Leviathan transported more than 98,000 troops. Naval History and Heritage Command 1 United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922 Frank A. Blazich Jr., PhD Naval History and Heritage Command Introduction This document is intended to provide readers with a chronological progression of the activities of the United States Navy and its involvement with World War I as an outside observer, active participant, and victor engaged in the war’s lingering effects in the postwar period. The document is not a comprehensive timeline of every action, policy decision, or ship movement. What is provided is a glimpse into how the 20th century’s first global conflict influenced the Navy and its evolution throughout the conflict and the immediate aftermath. The source base is predominately composed of the published records of the Navy and the primary materials gathered under the supervision of Captain Dudley Knox in the Historical Section in the Office of Naval Records and Library. A thorough chronology remains to be written on the Navy’s actions in regard to World War I. The nationality of all vessels, unless otherwise listed, is the United States. All errors and omissions are solely those of the author. Table of Contents 1914..................................................................................................................................................1 -

2014 Ships and Submarines of the United States Navy

AIRCRAFT CARRIER DDG 1000 AMPHIBIOUS Multi-Purpose Aircraft Carrier (Nuclear-Propulsion) THE U.S. NAvy’s next-GENERATION MULTI-MISSION DESTROYER Amphibious Assault Ship Gerald R. Ford Class CVN Tarawa Class LHA Gerald R. Ford CVN-78 USS Peleliu LHA-5 John F. Kennedy CVN-79 Enterprise CVN-80 Nimitz Class CVN Wasp Class LHD USS Wasp LHD-1 USS Bataan LHD-5 USS Nimitz CVN-68 USS Abraham Lincoln CVN-72 USS Harry S. Truman CVN-75 USS Essex LHD-2 USS Bonhomme Richard LHD-6 USS Dwight D. Eisenhower CVN-69 USS George Washington CVN-73 USS Ronald Reagan CVN-76 USS Kearsarge LHD-3 USS Iwo Jima LHD-7 USS Carl Vinson CVN-70 USS John C. Stennis CVN-74 USS George H.W. Bush CVN-77 USS Boxer LHD-4 USS Makin Island LHD-8 USS Theodore Roosevelt CVN-71 SUBMARINE Submarine (Nuclear-Powered) America Class LHA America LHA-6 SURFACE COMBATANT Los Angeles Class SSN Tripoli LHA-7 USS Bremerton SSN-698 USS Pittsburgh SSN-720 USS Albany SSN-753 USS Santa Fe SSN-763 Guided Missile Cruiser USS Jacksonville SSN-699 USS Chicago SSN-721 USS Topeka SSN-754 USS Boise SSN-764 USS Dallas SSN-700 USS Key West SSN-722 USS Scranton SSN-756 USS Montpelier SSN-765 USS La Jolla SSN-701 USS Oklahoma City SSN-723 USS Alexandria SSN-757 USS Charlotte SSN-766 Ticonderoga Class CG USS City of Corpus Christi SSN-705 USS Louisville SSN-724 USS Asheville SSN-758 USS Hampton SSN-767 USS Albuquerque SSN-706 USS Helena SSN-725 USS Jefferson City SSN-759 USS Hartford SSN-768 USS Bunker Hill CG-52 USS Princeton CG-59 USS Gettysburg CG-64 USS Lake Erie CG-70 USS San Francisco SSN-711 USS Newport News SSN-750 USS Annapolis SSN-760 USS Toledo SSN-769 USS Mobile Bay CG-53 USS Normandy CG-60 USS Chosin CG-65 USS Cape St. -

The Provision of American Medical Services at Or Via Southampton During WWII

The Provision of D-Day: American Medical Stories Services at or via from Southampton the Walls during WWII During the Maritime Archaeology Trust’s National Lottery Heritage Funded D-Day Stories from the Walls project, volunteers undertook online research into topics and themes linked to D-Day, Southampton, ships and people during the Second World War. Their findings were used to support project outreach and dissemination. This Research Article was undertaken by one of our volunteers and represents many hours of hard and diligent work. We would like to take this opportunity to thank all our amazing volunteers. Every effort has been made to trace the copyright hold-ers and obtain permission to reproduce this material. Please do get in touch with any enquiries or any information relating to any images or the rights holder. The Provision of American Medical Services at or via Southampton during WWII Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Planning for D-Day and Subsequently ............................................................................................. 2 Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley near Southampton ......................................................................... 3 Hospital Trains .................................................................................................................................. 5 Medical Services associated with 14th Port ................................................................................... -

GERMAN NAVY Records, 1854-1944 Reels M291-336A

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT GERMAN NAVY Records, 1854-1944 Reels M291-336A Historical Section The Admiralty Whitehall, London SW1 National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1959 CONTENTS Page 3 Historical note 5 Records of the Reichsmarine Amt, 1854-1913 9 Records of the Admiralstab der Marine, Abteilung B, 1880-1917 15 Records of the Oberkommando der Marine, Seekriegsleitung, 1939-44 16 Charts produced by the Reichsmarine, 1940-41 2 HISTORICAL NOTE The Imperial German Navy (Kaiserliche Marine) was created in 1871, succeeding the small navies of the Kingdom of Prussia and the North German Federation (1867-70). Its existence was recognised in the new constitution, but until 1888 it was commanded by generals and its role was mainly limited to coastal defence. In contrast to Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, Emperor Wilhelm II aspired to create a great German maritime empire. He became Grand Admiral of the German Navy and in 1889 made major changes to the organisation of the Admiralty. It was split into the Navy Cabinet, (Marine-Kabinett) responsible for appointments, promotions and issuing orders to naval forces, the Imperial High Command (Kaiserliche Oberkommando der Marine), responsible for ship deployments and strategy, and the Navy Office (Reichsmarine Amt ) responsible for the construction and maintenance of ships and obtaining supplies. The Navy Office was headed by a State Secretary, who was responsible to the Chancellor and who advised the Reichstag on naval matters. In 1899 the Imperial High Command was replaced by the Imperial Admiralty Staff (Admiralstab). Headed by Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, the Navy Office, which was located in the Leipzigerplatz in Berlin, was the more influential body. -

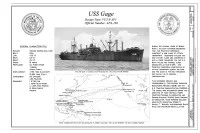

Design Type: VC2-S-AP5 Official Number: APA-168

USSGage Design Type: VC2-S-AP5 Official Number: APA-168 1- w u.. ~ 0 IJ) <( z t!) 0::: > GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS DURING THE CLOSING YEARS OF WORLD z~ WAR II, MILl T ARY PLANNERS REQUESTED ~ Q ~ w BUILDER: OREGON SHIPBUILDING CORP. THAT THE MARITIME COMMISSION <~ Q 0 "'~ <w BUlL T: 1944 CONSTRUCT A NEW CLASS OF ATTACK z w~ 11 Q ~ 0 LOA: 455'-0 TRANSPORTS. DESIGNERS UTILIZED THE w ~ 11 z BEAM: 62'-0 NEW VICTORY CLASS AND CONVERTED IT CX) "'u "~ 11 "'I- ~ -w ~ DRAFT: 24'-0 INTO A TROOP TRANSPORT FOR THE U.S. IW ~ ~ z <I~ 0 SPEED: 18 KNOTS NAVY CALLED THE HASKELL CLASS, ~ a._w z< ~ 0 <tffi u PROPULSION: OIL FIRED STEAM DESIGNATED AS VC2-S-AP5. THE w ~ w ~ z w~ iii TURBINE, MARITIME COMMISSION CONSTRUCTED 117 ~ zw ~ z t!)~ w SINGLE SHAFT ATTACK TRANSPORTS DURING THE WAR, <t~ 5 ~ t!)[fl w ~ DISPLACEMENT: 7,190 TONS (LIGHTSHIP) THE USS GAGE AT ANCHOR IN SAN FRANCISCO BAY, CIRCA 1946 PHOTO# NH98721 AND THE GAGE IS THE SOLE REMAINING l: u ~ 0 (/)~ ~ ~ (/) w 10,680 TONS (FULL) SHIP AFLOAT IN ITS ORIGINAL X ~ ::J ~ w • ~ CONFIGURATION. "u COMPLEMENT: 56 OFFICERS w ~ 9 ~ ~ ~ 480 ENLISTED Q w u ~ 11 .. 0 <:::. or;.·• ..,..""' 0 THIS RECORDING PROJECT WAS ~ ARMAMENT: I 5 /38 GUN w ' ~ ' Seattle, WA COSPONSORED BY THE HISTORIC AMERICAN ~ I 40MM QUAD MOUNT .. >- ' I- 4 40MM TWIN MOUNTS -~!',? _. -::.: -::; -:..: ~: :- /" Portland, OR ENGINEERING RECORD (HAER) AND THE 8 .~~ - -·- ----- --.. - It N z 10 20MM SINGLE -·- .- .-··-· -··- ·-. -· -::;;:::::-"···;:;=····- .. - .. _ .. ____ .. ____\_ U.S. MARITIME ADMINISTRATION (MARAD). ffi u - ...-··- ...~ .. -··- .. =·.-.=·... - .... - ·-·-····-.. ~ · an Francisco, CA :.:: > 1 MOUNTS 9 aJ!,. -

Luftwaffe Officer Career Summaries

Introduction Luftwaffe Officer Career Summaries Version: 01 April 2019. Introduction Terminology Bibliography By: Henry L. deZeng IV and Douglas G. Stankey I N T R O D U C T I O N This work is the sum total of many years of collecting data concerning the careers of some of the officers of the Luftwaffe during the Third Reich period. In a change in policy, we now include all commissioned officers known to have served in the Luftwaffe during the Third Reich period. Thus the 73,500 officers represented here are only a fraction of the approximately 120,000 officers and senior officials (Beamte) of officer rank that the Luftwaffe possessed over this period. Nor is the data complete. Due to the near total destruction of official records, we resorted to taking information from the microfilms of the few surviving records and from better quality books. An estimated 75% of the entries were taken from the thousands of wartime Luftwaffe personnel branch’s officer assignment and promotion orders that constitute a microfilmed collection of some 50,000 pages of documentation. Due to the fragmentary nature of our sources, there have been some unavoidable errors for data of those with similar or identical names. While every reasonable effort has been made to distinguish individuals, some comingling of data between them has taken place. Another related issue has been duplicate entries for a given person. These problems are insidious and are corrected as they are found. The level of detail per individual varies from near complete to only a trace reference. -

The Jersey Bounce Fall 2009

USS New Jersey Veterans, Inc. “THE JERSEY BOUNCE” Fall 2009 Issue Email - WWW.USSNEWJERSEY.ORG LPD 21 USS NEW YORK The 22nd reunion was held at the Crowne Plaza Riverfront Hotel in Jacksonville, Florida, October 7th through October 11th, 2009. The organization enjoyed a very successful reunion. The Memorial Service, St. Augustine and Jacksonville tours, Dinner Cruise, Welcome Aboard Dinner, and a Dinner Dance Banquet were well at- tended. We want to thank the reunion committee for a job well done. The reunion committee worked hard in providing this annual opportunity for our shipmates to become reacquainted with old friends and shipmates. These reunions are a great opportunity to make new friends, or just reminisce sea stories of bygone days. The days of the battleship, the most feared dreadnaught on the high seas, are long gone, but the battleship sailors live on and on. Newer and more deadly ships are joining the fleet providing firepower that we can- not imagine only conjecture. USS New Jersey Veterans Inc Officer & Directors President / Director Vice President / Director Joe DiMaria Ernest Dalton 645 Brisa Ct. 7143 Rolling Hill Lane Chesapeake, VA 23322 San Antonio, Texas 78227 757-549-2178 210-275-7886 [email protected] [email protected] Secretary/Director Treasurer/Director Membership/Director A.J. Smith John Pete Vance Steve Sheehan 538 Kiddsville Road 1541 Hayden Rd 1209 Cumberland RD Fishersville, VA 22939 Deland, FL 32724 Abington, PA 19001 540-943-2862 386-736-3231 215-887-7583 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Master at Arms Liaison/Director Small Stores/Director Joe Porambo Mark Babcock John Pete Vance 1503 Elder Ave 5231 El Monte St. -

Syndeck™ Ultra Lightweight Underlayment Used on the USS New York (LPD-21)

For Release: Contact: NEWS Jill See Immediate Marketing Specialist T: 562-236-1175 F: 562-944-9958 SynDeck™ Ultra Lightweight Underlayment Used on the USS New York (LPD-21) PLACENTIA, CA (June 2009) – The military ship building/repair industry is highly focused on the efficiencies that come from ultra lightweight materials. However, most deck underlayments do not meet the lightweight requirements of the marine industry. California-based Epmar Corporation, with more than 20 years of experience providing the marine industry with primary deck coatings and underlayments, designed the SynDeck™ product line to meet the specific needs of surface materials, application and underlayment performance requirements for military and commercial marine vessels. SynDeck™ Ultra Lightweight Underlayment gives the highest possible performance with the lightest possible weight, and provides excellent corrosion resistance (MilSpec 3135). Northrop-Grumman Ship Systems, Avondale Operations, located in the greater New Orleans area, is currently building new LPD-class amphibious transport ships using Epmar’s SynDeck™ Ultra Lightweight Underlayment in all inhabited interior deck spaces. This new class of ship includes the LPD-21 USS New York, which was named to honor those that died in the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center. In fact, the bow stem of this particular ship was forged from reclaimed steel from World Trade Center buildings. When completed, the USS New York is slated to return to New York City to be commissioned into the US Navy, and will be operating out of the Norfolk Naval Shipyard. Gary Hayes, sales manager for the SynDeck™ line said, “Epmar Corporation is extremely proud to have SynDeck™ Ultra Lightweight Underlayment, SS1290, used for the deck underlayment on this class of ship, and on the USS New York in particular.” SynDeck™ is a complete line of deck underlayment products and systems used in the construction, overhaul and repair of decking and other surfaces in the marine environment. -

2019 China Military Power Report

OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China ANNUAL REPORT TO CONGRESS Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2019 Office of the Secretary of Defense Preparation of this report cost the Department of Defense a total of approximately $181,000 in Fiscal Years 2018-2019. This includes $12,000 in expenses and $169,000 in DoD labor. Generated on 2019May02 RefID: E-1F4B924 OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2019 A Report to Congress Pursuant to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2000, as Amended Section 1260, “Annual Report on Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, Public Law 115-232, which amends the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2000, Section 1202, Public Law 106-65, provides that the Secretary of Defense shall submit a report “in both classified and unclassified form, on military and security developments involving the People’s Republic of China. The report shall address the current and probable future course of military-technological development of the People’s Liberation Army and the tenets and probable development of Chinese security strategy and military strategy, and of the military organizations and operational concepts supporting such development over the next 20 years. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index.