The Law of Submarine Warfare Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navy Columbia-Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program

Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 14, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R41129 Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program Summary The Navy’s Columbia (SSBN-826) class ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) program is a program to design and build a class of 12 new SSBNs to replace the Navy’s current force of 14 aging Ohio-class SSBNs. Since 2013, the Navy has consistently identified the Columbia-class program as the Navy’s top priority program. The Navy procured the first Columbia-class boat in FY2021 and wants to procure the second boat in the class in FY2024. The Navy’s proposed FY2022 budget requests $3,003.0 (i.e., $3.0 billion) in procurement funding for the first Columbia-class boat and $1,644.0 million (i.e., about $1.6 billion) in advance procurement (AP) funding for the second boat, for a combined FY2022 procurement and AP funding request of $4,647.0 million (i.e., about $4.6 billion). The Navy’s FY2022 budget submission estimates the procurement cost of the first Columbia- class boat at $15,030.5 million (i.e., about $15.0 billion) in then-year dollars, including $6,557.6 million (i.e., about $6.60 billion) in costs for plans, meaning (essentially) the detail design/nonrecurring engineering (DD/NRE) costs for the Columbia class. (It is a long-standing Navy budgetary practice to incorporate the DD/NRE costs for a new class of ship into the total procurement cost of the first ship in the class.) Excluding costs for plans, the estimated hands-on construction cost of the first ship is $8,473.0 million (i.e., about $8.5 billion). -

Should the United States Develop and Employ Strategic Information Warfare Capabilities?

Should the United States develop and employ strategic information warfare capabilities? Information technologies have transformed U.S. and, indeed, international society. The ways we socialize, educate and inform ourselves, engage in business and practice our religions have been changed, and in many cases now rely, on digital information and communication. Can warfare—the defense and promotion of our national security and interests—be exempt under any circumstances from developing and employing the latest information strategies? Is this even a choice in the 21st century, much less a hard choice? Information warfare has been variously defined by different analysts but a standard general definition, as provided by the U.S. Air Force is “any action to deny, exploit, corrupt, or destroy the enemy’s information and its functions; protecting ourselves against the actions and exploiting our own information operations.” The goal of information war is now frequently described as “information dominance.” (1) Major General Kenneth Minihan, stated, “information dominance is not ‘my pile of information is bigger than yours’…It is a way of increasing our capabilities by using that information to make right decisions, (and) apply them faster than the enemy can. It is a way to alter the enemy’s entire perception of reality. It is a method of using all the information at our disposal to predict (and affect) what happens tomorrow before the enemy even jumps out of bed and thinks about what to do today.” (2) Pro: Information warfare is not a new concept that arose with the Internet. Information has always been a decisive factor in deciding the victory or defeat of one military force over another. -

Unlocking NATO's Amphibious Potential

November 2020 Perspective EXPERT INSIGHTS ON A TIMELY POLICY ISSUE J.D. WILLIAMS, GENE GERMANOVICH, STEPHEN WEBBER, GABRIELLE TARINI Unlocking NATO’s Amphibious Potential Lessons from the Past, Insights for the Future orth Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) members maintain amphibious capabilities that provide versatile and responsive forces for crisis response and national defense. These forces are routinely employed in maritime Nsecurity, noncombatant evacuation operations (NEO), counterterrorism, stability operations, and other missions. In addition to U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) and U.S. Navy forces, the Alliance’s amphibious forces include large ships and associated landing forces from five nations: France, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and the United Kingdom (UK). Each of these European allies—soon to be joined by Turkey—can conduct brigade-level operations, and smaller elements typically are held at high readiness for immediate response.1 These forces have been busy. Recent exercises and operations have spanned the littorals of West and North Africa, the Levant, the Gulf of Aden and Arabian Sea, the Caribbean, and the Pacific. Given NATO’s ongoing concerns over Russia’s military posture and malign behavior, allies with amphibious capabilities have also been exploring how these forces could contribute to deterrence or, if needed, be employed as part of a C O R P O R A T I O N combined and joint force in a conflict against a highly some respects, NATO’s ongoing efforts harken back to the capable nation-state. Since 2018, NATO’s headquarters Cold War, when NATO’s amphibious forces routinely exer- and various commands have undertaken initiatives and cised in the Mediterranean and North Atlantic as part of a convened working groups to advance the political intent broader strategy to deter Soviet aggression. -

The Provision of American Medical Services at Or Via Southampton During WWII

The Provision of D-Day: American Medical Stories Services at or via from Southampton the Walls during WWII During the Maritime Archaeology Trust’s National Lottery Heritage Funded D-Day Stories from the Walls project, volunteers undertook online research into topics and themes linked to D-Day, Southampton, ships and people during the Second World War. Their findings were used to support project outreach and dissemination. This Research Article was undertaken by one of our volunteers and represents many hours of hard and diligent work. We would like to take this opportunity to thank all our amazing volunteers. Every effort has been made to trace the copyright hold-ers and obtain permission to reproduce this material. Please do get in touch with any enquiries or any information relating to any images or the rights holder. The Provision of American Medical Services at or via Southampton during WWII Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Planning for D-Day and Subsequently ............................................................................................. 2 Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley near Southampton ......................................................................... 3 Hospital Trains .................................................................................................................................. 5 Medical Services associated with 14th Port ................................................................................... -

Gao-20-257T, Navy Maintenance

United States Government Accountability Office Testimony Before the Subcommittees on Seapower and Readiness and Management Support, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate For Release on Delivery Expected at 10:00 a.m. ET Wednesday, December 4, 2019 NAVY MAINTENANCE Persistent and Substantial Ship and Submarine Maintenance Delays Hinder Efforts to Rebuild Readiness Statement of Diana C. Maurer Director Defense Capabilities and Management GAO-20-257T December 4, 2019 NAVY MAINTENANCE Persistent and Substantial Ship and Submarine Maintenance Delays Hinder Efforts to Rebuild Readiness Highlights of GAO-20-257T, a testimony before the Subcommittees on Seapower and Readiness and Management Support, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found The 2018 National Defense Strategy The Navy continues to face persistent and substantial maintenance delays that emphasizes that restoring and retaining affect the majority of its maintenance efforts and hinder its attempts to restore readiness is critical to success in the readiness. From fiscal year 2014 to the end of fiscal year 2019, Navy ships have emerging security environment. The spent over 33,700 more days in maintenance than expected. The Navy was Navy is working to rebuild its readiness unable to complete scheduled ship maintenance on time for about 75 percent of while also growing and modernizing its the maintenance periods conducted during fiscal years 2014 through 2019, with aging fleet of ships. A critical component more than half of the delays in fiscal year 2019 exceeding 90 days. When of rebuilding Navy readiness is maintenance is not completed on time, fewer ships are available for training or implementing sustainable operational operations, which can hinder readiness. -

Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress

Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress (name redacted) Specialist in Naval Affairs December 13, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RS22478 Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress Summary Names for Navy ships traditionally have been chosen and announced by the Secretary of the Navy, under the direction of the President and in accordance with rules prescribed by Congress. Rules for giving certain types of names to certain types of Navy ships have evolved over time. There have been exceptions to the Navy’s ship-naming rules, particularly for the purpose of naming a ship for a person when the rule for that type of ship would have called for it to be named for something else. Some observers have perceived a breakdown in, or corruption of, the rules for naming Navy ships. On July 13, 2012, the Navy submitted to Congress a 73-page report on the Navy’s policies and practices for naming ships. For ship types now being procured for the Navy, or recently procured for the Navy, naming rules can be summarized as follows: The first Ohio replacement ballistic missile submarine (SBNX) has been named Columbia in honor of the District of Columbia, but the Navy has not stated what the naming rule for these ships will be. Virginia (SSN-774) class attack submarines are being named for states. Aircraft carriers are generally named for past U.S. Presidents. Of the past 14, 10 were named for past U.S. Presidents, and 2 for Members of Congress. Destroyers are being named for deceased members of the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard, including Secretaries of the Navy. -

Introduction 1 Introduction in a Recent Review of Guy Halsall's Warfare And

introduction 1 INTRODUCTION In a recent review of Guy Halsall’s Warfare and Society in the Barbarian West, 450-900, which is ostensibly meant to be a new standard in the field, Bryan Ward-Perkins approves of the author’s findings, summarizing of early medieval warfare that: It remains very difficult to imagine a seventh- or eighth-century army, except as a hairy and ill-equipped horde, or as a Beowulfian band of heroes, and almost impossible to envisage what such an army did when faced with an obstacle such as a walled town[.]1 Ward-Perkins is being willfully—not to say wonderfully—provocative. He is well aware of the substantial and growing body of scholarship on early medieval warfare that has rendered clichés of hairy barbarians obsolete.2 But quips aside, he highlights a serious gap in existing historiography. While many scholars recognize the similarity (and to varying extents con- tinuity) between Roman and high medieval siege warfare, this has never been demonstrated in any detail. Hence, a notable number of scholars favor a minimalist interpretation of warfare in which the siege is accorded little importance, especially in the West, arguing that post-Roman society lacked the necessary demographic, economic, organizational and even cultural prerequisites. Continuity of military institutions is unquestioned in the case of the East Roman, or Byzantine Empire, but Byzantine siege warfare has received only sporadic attention, and it has been even more marginal in explaining the Islamic expansion.3 This study seeks to examine the organization and practice of siege war- fare among the major successor states of the former Roman Empire: The 1 Ward-Perkins 2006, reviewing Halsall 2003. -

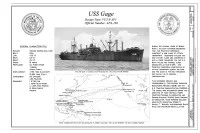

Design Type: VC2-S-AP5 Official Number: APA-168

USSGage Design Type: VC2-S-AP5 Official Number: APA-168 1- w u.. ~ 0 IJ) <( z t!) 0::: > GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS DURING THE CLOSING YEARS OF WORLD z~ WAR II, MILl T ARY PLANNERS REQUESTED ~ Q ~ w BUILDER: OREGON SHIPBUILDING CORP. THAT THE MARITIME COMMISSION <~ Q 0 "'~ <w BUlL T: 1944 CONSTRUCT A NEW CLASS OF ATTACK z w~ 11 Q ~ 0 LOA: 455'-0 TRANSPORTS. DESIGNERS UTILIZED THE w ~ 11 z BEAM: 62'-0 NEW VICTORY CLASS AND CONVERTED IT CX) "'u "~ 11 "'I- ~ -w ~ DRAFT: 24'-0 INTO A TROOP TRANSPORT FOR THE U.S. IW ~ ~ z <I~ 0 SPEED: 18 KNOTS NAVY CALLED THE HASKELL CLASS, ~ a._w z< ~ 0 <tffi u PROPULSION: OIL FIRED STEAM DESIGNATED AS VC2-S-AP5. THE w ~ w ~ z w~ iii TURBINE, MARITIME COMMISSION CONSTRUCTED 117 ~ zw ~ z t!)~ w SINGLE SHAFT ATTACK TRANSPORTS DURING THE WAR, <t~ 5 ~ t!)[fl w ~ DISPLACEMENT: 7,190 TONS (LIGHTSHIP) THE USS GAGE AT ANCHOR IN SAN FRANCISCO BAY, CIRCA 1946 PHOTO# NH98721 AND THE GAGE IS THE SOLE REMAINING l: u ~ 0 (/)~ ~ ~ (/) w 10,680 TONS (FULL) SHIP AFLOAT IN ITS ORIGINAL X ~ ::J ~ w • ~ CONFIGURATION. "u COMPLEMENT: 56 OFFICERS w ~ 9 ~ ~ ~ 480 ENLISTED Q w u ~ 11 .. 0 <:::. or;.·• ..,..""' 0 THIS RECORDING PROJECT WAS ~ ARMAMENT: I 5 /38 GUN w ' ~ ' Seattle, WA COSPONSORED BY THE HISTORIC AMERICAN ~ I 40MM QUAD MOUNT .. >- ' I- 4 40MM TWIN MOUNTS -~!',? _. -::.: -::; -:..: ~: :- /" Portland, OR ENGINEERING RECORD (HAER) AND THE 8 .~~ - -·- ----- --.. - It N z 10 20MM SINGLE -·- .- .-··-· -··- ·-. -· -::;;:::::-"···;:;=····- .. - .. _ .. ____ .. ____\_ U.S. MARITIME ADMINISTRATION (MARAD). ffi u - ...-··- ...~ .. -··- .. =·.-.=·... - .... - ·-·-····-.. ~ · an Francisco, CA :.:: > 1 MOUNTS 9 aJ!,. -

Issue 8, Volume 59, April 30 1985 Ckland University Students' Association EDITORIAL

ngs duldoon 23-27 APR! 1 & 6 PM S2 & S4 Issue 8, Volume 59, April 30 1985 ckland University Students' Association EDITORIAL Craccum is edited by Pam Goode and Birgitta On Sunday, 21 April a woman was viciously raped in a manner whi imitated a rape scene screened on TVNZ the previous evening. And all 1 I Noble. The following people helped on this issue: week past, I have been subjected to the sensationalist accounts of first f Ian Grant, Andrew Jull, Karin Bos, Henry Knapp blaming the traffic officers (who would not allow the woman to 1 Harrison, Darius, Cornelius Stone, Dylan home, because of her blood alcohol level and would not drive her home) fori Horrocks, Robyn Hodge, Wallis, John Bates, occurence of the rape and then the PSA excusing the actions of the office Mark Allen & Janet Cole. alluding to the lack of staff. For their contributions thanks to: Bidge Smith, Whilst there is no doubt the traffic officers are partially to blame, thei Jonathan Blakeman, Colin Patterson, Adam Ross, reason for the rape has been ignored both by the press and in the statementi the various people concerned. Implicit in the argument surrounding | Kupe, Cornelius Stone. For photography thanks to Andrew Jull. culpability of the traffic officers is the assumption that the streets are nots And a special thank you to Janina Adamiak and J o at night for women, and therefore the woman concerned should not havel eft alone. But this assumption blames the victim, the woman for assertir Imrie. right to be wherever she wishes. -

China Naval Modernization: Implications for US Navy Capabilities

China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress Updated May 21, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33153 China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities Summary In an era of renewed great power competition, China’s military modernization effort, including its naval modernization effort, has become the top focus of U.S. defense planning and budgeting. China’s navy, which China has been steadily modernizing for more than 25 years, since the early to mid-1990s, has become a formidable military force within China’s near-seas region, and it is conducting a growing number of operations in more-distant waters, including the broader waters of the Western Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and waters around Europe. China’s navy is viewed as posing a major challenge to the U.S. Navy’s ability to achieve and maintain wartime control of blue-water ocean areas in the Western Pacific—the first such challenge the U.S. Navy has faced since the end of the Cold War—and forms a key element of a Chinese challenge to the long- standing status of the United States as the leading military power in the Western Pacific. China’s naval modernization effort encompasses a wide array of platform and weapon acquisition programs, including anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), submarines, surface ships, aircraft, unmanned vehicles (UVs), and supporting C4ISR (command and control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) systems. China’s naval modernization effort also includes improvements in maintenance and logistics, doctrine, personnel quality, education and training, and exercises. -

Winter 2019 Full Issue the .SU

Naval War College Review Volume 72 Article 1 Number 1 Winter 2019 2019 Winter 2019 Full Issue The .SU . Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Naval War College, The .SU . (2019) "Winter 2019 Full Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 72 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol72/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naval War College: Winter 2019 Full Issue Winter 2019 Volume 72, Number 1 Winter 2019 Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2019 1 Naval War College Review, Vol. 72 [2019], No. 1, Art. 1 Cover Aerial view of an international container cargo ship. In “Ships of State?,” Christopher R. O’Dea describes how China COSCO Shipping Corporation Limited has come to control a rapidly expanding network of ports and terminals, ostensibly for commercial purposes, but has thereby gained the ability to project power through the increased physical presence of its naval vessels—turning the oceans that historically have protected the United States from foreign threats into a venue in which China can challenge U.S. interests. Credit: Getty Images https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol72/iss1/1 2 Naval War College: Winter 2019 Full Issue NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REVIEW Winter 2019 Volume 72, Number 1 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE PRESS 686 Cushing Road Newport, RI 02841-1207 Published by U.S. -

Appendix A. Navy Activity Descriptions

Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing Draft EIS/OEIS June 2017 APPENDIX A Navy Activity Descriptions Appendix A Navy Activity Descriptions Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing Draft EIS/OEIS June 2017 This page intentionally left blank. Appendix A Navy Activity Descriptions Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing Draft EIS/OEIS June 2017 Draft Environmental Impact Statement/Overseas Environmental Impact Statement Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing TABLE OF CONTENTS A. NAVY ACTIVITY DESCRIPTIONS ................................................................................................ A-1 A.1 Description of Sonar, Munitions, Targets, and Other Systems Employed in Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing Events .................................................................. A-1 A.1.1 Sonar Systems and Other Acoustic Sources ......................................................... A-1 A.1.2 Munitions .............................................................................................................. A-7 A.1.3 Targets ................................................................................................................ A-11 A.1.4 Defensive Countermeasures ............................................................................... A-13 A.1.5 Mine Warfare Systems ........................................................................................ A-13 A.1.6 Military Expended Materials ............................................................................... A-16 A.2 Training Activities ..................................................................................................