The Place of Language and the Language of Place in the Basque Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of Eta

Cátedra de Economía del Terrorismo UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales DISMANTLING TERRORIST ’S ECONOMICS : THE CASE OF ETA MIKEL BUESA* and THOMAS BAUMERT** *Professor at the Universidad Complutense of Madrid. **Professor at the Catholic University of Valencia Documento de Trabajo, nº 11 – Enero, 2012 ABSTRACT This article aims to analyze the sources of terrorist financing for the case of the Basque terrorist organization ETA. It takes into account the network of entities that, under the leadership and oversight of ETA, have developed the political, economic, cultural, support and propaganda agenda of their terrorist project. The study focuses in particular on the periods 1993-2002 and 2003-2010, in order to observe the changes in the financing of terrorism after the outlawing of Batasuna , ETA's political wing. The results show the significant role of public subsidies in finance the terrorist network. It also proves that the outlawing of Batasuna caused a major change in that funding, especially due to the difficulty that since 2002, the ETA related organizations had to confront to obtain subsidies from the Basque Government and other public authorities. Keywords: Financing of terrorism. ETA. Basque Country. Spain. DESARMANDO LA ECONOMÍA DEL TERRORISMO: EL CASO DE ETA RESUMEN Este artículo tiene por objeto el análisis de las fuentes de financiación del terrorismo a partir del caso de la organización terrorista vasca ETA. Para ello se tiene en cuenta la red de entidades que, bajo el liderazgo y la supervisión de ETA, desarrollan las actividades políticas, económicas, culturales, de propaganda y asistenciales en las que se materializa el proyecto terrorista. -

2005 Page 1 of 9 2005 Country Report on Human Rights Practices

2005 Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Spain Page 1 of 9 Facing the Threat Posed by Iranian Regime | Daily Press Briefing | Other News... Spain Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006 Spain, with a population of approximately 43 million, is a parliamentary democracy with a constitutional monarch. The March 2004 national election was free and fair. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces. The government generally respected the human rights of its citizens; although there were a few problems in some areas, the law and judiciary provide effective means of addressing individual instances of abuse. The following problems were reported: detainees, foreigners, and illegal immigrants were reportedly abused and mistreated by some members of the security forces lengthy pretrial detention and delays in some trials some societal violence against immigrants domestic violence against women trafficking in women and teenage girls for the purpose of sexual exploitation societal discrimination against Roma The terrorist group Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) continued its campaign of bombings. ETA sympathizers also continued a campaign of street violence and vandalism in the Basque region intended to intimidate politicians, academics, and journalists. Islamist groups linked to those who killed 191 and injured more than one thousand persons in March 2004 remained active. The government continued to investigate and make arrests. RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life The government or its agents did not commit any politically motivated killings; however, one detainee died while in custody during the year. -

How Can a Modern History of the Basque Country Make Sense? on Nation, Identity, and Territories in the Making of Spain

HOW CAN A MODERN HISTORY OF THE BASQUE COUNTRY MAKE SENSE? ON NATION, IDENTITY, AND TERRITORIES IN THE MAKING OF SPAIN JOSE M. PORTILLO VALDES Universidad del Pais Vasco Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada (Reno) One of the more recurrent debates among Basque historians has to do with the very object of their primary concern. Since a Basque political body, real or imagined, has never existed before the end of the nineteenth century -and formally not until 1936- an «essentialist» question has permanently been hanging around the mind of any Basque historian: she might be writing the histo- ry of an non-existent subject. On the other hand, the heaviness of the «national dispute» between Basque and Spanish identities in the Spanish Basque territories has deeply determined the mean- ing of such a cardinal question. Denying the «other's» historicity is a very well known weapon in the hands of any nationalist dis- course and, conversely, claiming to have a millenary past behind one's shoulders, or being the bearer of a single people's history, is a must for any «national» history. Consequently, for those who consider the Spanish one as the true national identity and the Basque one just a secondary «decoration», the history of the Basque Country simply does not exist or it refers to the last six decades. On the other hand, for those Basques who deem the Spanish an imposed identity, Basque history is a sacred territory, the last refuge for the true identity. Although apparently uncontaminated by politics, Basque aca- demic historiography gently reproduces discourses based on na- - 53 - ESPANA CONTEMPORANEA tionalist assumptions. -

Onomástica Genérica Roncalesa Ligada a Casas Y Edificios

Onomástica genérica roncalesa ligada a casas y edificios Juan Karlos LOPEZ-MUGARTZA IRIARTE Universidad Pública de Navarra/Nafarroako Unibertsitatea Publikoa [email protected] Resumen: El objetivo del presente artículo es Abstract: The objective of this article is to show mostrar el léxico genérico del valle de Roncal en the generic lexicon of the Valley of Roncal in Navarra ligado a la oiconimia que es la ciencia Navarre linked to the oiconimy, science that que estudia los nombres de las casas. Es decir, studies the names of the houses. It means that no se citan los nombres propios de las casas, ni the proper names of the houses are not men- de las edificaciones del valle, sino que se estu- tioned, nor of the constructions of the valley, but dian los nombres genéricos de esas casas y de the generic names of those houses and those esas edificaciones atendiendo al uso que se les buildings are studied according to the use that da (lugar de habitación humana, lugar de repo- is given to them (place of human habitation, so para el ganado, etc.), a los elementos que la resting place for livestock, etc.), the elements componen (desagües, tejados, chimeneas, etc.) that compose it (drains, roofs, chimneys, etc.) y a los elementos que la circundan (huertos, es- and the elements that surround it (orchards, pacios entre las casas, caminos, calles, barrios, spaces between houses, roads, streets, neigh- etc.). borhoods, etc.). El presente trabajo se basa en el estudio de la The present work is based on the study of the documentación conservada en los archivos ron- documentation collected in the Roncal archives caleses y en su comparación con el habla viva and in its comparison with the live speech that que se ha recogido mediante encuesta oral. -

Pais Vasco 2018

The País Vasco Maribel’s Guide to the Spanish Basque Country © Maribel’s Guides for the Sophisticated Traveler ™ August 2018 [email protected] Maribel’s Guides © Page !1 INDEX Planning Your Trip - Page 3 Navarra-Navarre - Page 77 Must Sees in the País Vasco - Page 6 • Dining in Navarra • Wine Touring in Navarra Lodging in the País Vasco - Page 7 The Urdaibai Biosphere Reserve - Page 84 Festivals in the País Vasco - Page 9 • Staying in the Urdaibai Visiting a Txakoli Vineyard - Page 12 • Festivals in the Urdaibai Basque Cider Country - Page 15 Gernika-Lomo - Page 93 San Sebastián-Donostia - Page 17 • Dining in Gernika • Exploring Donostia on your own • Excursions from Gernika • City Tours • The Eastern Coastal Drive • San Sebastián’s Beaches • Inland from Lekeitio • Cooking Schools and Classes • Your Western Coastal Excursion • Donostia’s Markets Bilbao - Page 108 • Sociedad Gastronómica • Sightseeing • Performing Arts • Pintxos Hopping • Doing The “Txikiteo” or “Poteo” • Dining In Bilbao • Dining in San Sebastián • Dining Outside Of Bilbao • Dining on Mondays in Donostia • Shopping Lodging in San Sebastián - Page 51 • Staying in Bilbao • On La Concha Beach • Staying outside Bilbao • Near La Concha Beach Excursions from Bilbao - Page 132 • In the Parte Vieja • A pretty drive inland to Elorrio & Axpe-Atxondo • In the heart of Donostia • Dining in the countryside • Near Zurriola Beach • To the beach • Near Ondarreta Beach • The Switzerland of the País Vasco • Renting an apartment in San Sebastián Vitoria-Gasteiz - Page 135 Coastal -

Spanish Censuses of the Sixteenth Century

BYU Family Historian Volume 1 Article 5 9-1-2002 Spanish Censuses of the Sixteenth Century George R. Ryskamp Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byufamilyhistorian Recommended Citation The BYU Family Historian, Vol. 1 (Fall 2002) p.14-22 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Family Historian by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Spanish Censuses of the Sixteenth Century by George R. Ryskamp, J.D., AG A genealogist tracing family lines backwards This article will be organized under a combination of in Spain will almost certainly find a lack of records the first and second approach, looking both at the that have sustained his research as he reaches the year nature of the original order to take the census and 1600. Most significantly, sacramental records in where it may be found, and identifying the type of about half ofthe parishes begin in or around the year census to be expected and the detail of its content. 1600, likely reflecting near universal acceptance and application of the order for the creation of baptismal Crown Censuses and marriage records contained in the decrees of the The Kings ofCastile ordered several censuses Council of Trent issued in 1563. 1 Depending upon taken during the years 1500 to 1599. Some survive the diocese between ten and thirty percent of only in statistical summaries; others in complete lists. 5 parishes have records that appear to have been In each case a royal decree ordered that local officials written in response to earlier reforms such as a (usually the municipal alcalde or the parish priest) similar decrees from the Synod of Toledo in 1497. -

CARNAVALES EN NAVARRA 2016 Definitivo

CARNAVALES EN NAVARRA 2016 NAFARROAKO INAUTERIAK / CARNAVALS EN NAVARRE / CARNIVALS IN NAVARRA Población Teléfono Fecha Personaje central Actividad principal Desfile de chicos con bota con la que pegan, los Cascabobos y de chicas con rostros ocultos, las Mascaritas. Cuestación por las casas y recogida 948336690 de huevos y chistorra para posterior elaboración de pinchos que se 9 de febrero CASCABOBOS AOIZ Marisol repartirán durante la quema de Ziriko y Kapusai, que representan a los MASCARITAS casa Cultura asesinos a causa de los que se cerró la calle Maldita. Durante el desfile, cascabobos y mascaritas atraviesan esa calle con antorchas para purificarla. Domingo 7 , carnaval infantil. Martes 9 , carnaval rural: desfile con txistularis, charanga y gaiteros. Baile típico, "Momotxorroen Dantza". Personajes vestidos con abarcas, pantalón azul y camisa blanca, remangada y manchada al igual que los brazos de sangre de cordero o de cerdo. En la cabeza llevan una cesta de la que cuelgan pieles de oveja y cuernos de vaca. De los enormes cuernos cuelgan sobre la cara MOMOTXORROS ALTSASU/ 948 56 21 61 crines de caballo. A la espalda los cencerros causan un verdadero 7, 9 y 13 de febrero MASCARITAS ALSASUA (Ayto) estruendo y en la mano llevan un "Sarde" para amedrentar al JUAN TRAMPOSO numeroso público asistente. En el desfile le siguen las brujas vestidas de negro , mascaritas (envueltas en sobrecamas multicolores, zapatos viejos, y el rostro cubierto de puntillas), "Juantramposos" (Personajes rellenos de hierba seca emparentados con el ziripot de Lantz y los Zaku zaharrak de lesaka), el macho cabrío y algunos personajes que representan un cuadro de labranza ritual. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Hondarribia Walking Tour Way of St

countrywalkers.com 800.234.6900 Spain: San Sebastian, Bilbao & Basque Country Flight + Tour Combo Itinerary Free-roaming horses wander the green pastures atop Mount Jaizkibel, where your walk brings panoramic views extending clear across Spain into southern France—from the Bay of Biscay to the Pyrenees. You’re on a walking tour in the Basque Country, a unique corner of Europe with its own ancient language and culture. You’ve just begun exploring this fascinating region—from Bilbao’s cutting-edge architecture to Hendaye’s beaches to the mountainous interior. Your week ahead also promises tasty glimpses of local culinary culture: a Basque cooking class, a festive dinner at a traditional gastronomic club, a homemade feast in a hillside farmhouse…. Speaking of food, isn’t it about time to begin your scenic seaward descent through the vineyards for lunch and wine tasting? On egin! (Bon appetit!) Highlights Join a private gastronomic club, or txoko, for an exclusive dinner as the members share their love of Basque cuisine. Live like royalty in a setting so beautiful it earned the honor of hosting Louis XIV and Maria Theresa’s wedding in St. Jean de Luz. Experience the vibrant nightlife in a Basque wine bar. Stroll the seaside paths that Spanish aristocracy once wandered in San Sebastián. Tour the world-famous Guggenheim Museum – one of the largest museums on Earth and an architectural phenomenon. Satisfy your cravings in a region with more Michelin-star rated restaurants than Paris. Rest your mind and body in a restored 17th-century palace, or jauregia. 1 / 10 countrywalkers.com 800.234.6900 Participate in a cooking demonstration of traditional Basque cuisine. -

Navarra, Comunidad Foral De

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE ARQUITECTURA, VIVIENDA Y SUELO Navarra, Comunidad Foral de CÓDIGO POBLACIÓN TIPO FIGURA AÑO PUBLIC. PROVINCIA INE MUNICIPIO 2018 PLANEAMIENTO APROBACIÓN Navarra 31001 Abáigar 87 Normas Subsidiarias 1997 Navarra 31002 Abárzuza/Abartzuza 550 Plan General 1999 Navarra 31003 Abaurregaina/Abaurrea Alta 121 Plan General 2016 Navarra 31004 Abaurrepea/Abaurrea Baja 33 Plan General 2016 Navarra 31005 Aberin 356 Plan General 2003 Navarra 31006 Ablitas 2.483 Plan General 2015 Navarra 31007 Adiós 156 Plan General 2019 Navarra 31008 Aguilar de Codés 72 Plan General 2010 Navarra 31009 Aibar/Oibar 791 Plan General 2009 Navarra 31011 Allín/Allin 850 Plan General 2015 Navarra 31012 Allo 983 Plan General 2002 Navarra 31010 Altsasu/Alsasua 7.407 Plan General 2003 Navarra 31013 Améscoa Baja 730 Plan General 2003 Navarra 31014 Ancín/Antzin 340 Normas Subsidiarias 1995 Navarra 31015 Andosilla 2.715 Plan General 1999 Navarra 31016 Ansoáin/Antsoain 10.739 Plan General 2019 Navarra 31017 Anue 485 Plan General 1997 Navarra 31018 Añorbe 568 Plan General 2012 Navarra 31019 Aoiz/Agoitz 2.624 Plan General 2004 Navarra 31020 Araitz 525 Plan General 2015 Navarra 31025 Arakil 949 Normas Subsidiarias 2014 Navarra 31021 Aranarache/Aranaratxe 70 Sin Planeamiento 0 Navarra 31023 Aranguren 10.512 Normas Subsidiarias 1995 Navarra 31024 Arano 116 Plan General 1997 Navarra 31022 Arantza 614 Normas Subsidiarias 1994 Navarra 31026 Aras 157 Plan General 2008 Navarra 31027 Arbizu 1.124 Plan General 2017 Navarra 31028 Arce/Artzi 264 Plan General 1997 Navarra -

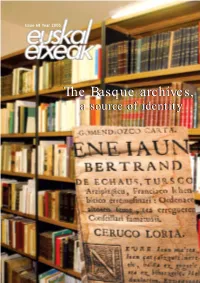

The Basquebasque Archives,Archives, Aa Sourcesource Ofof Identityidentity TABLE of CONTENTS

Issue 68 Year 2005 TheThe BasqueBasque archives,archives, aa sourcesource ofof identityidentity TABLE OF CONTENTS GAURKO GAIAK / CURRENT EVENTS: The Basque archives, a source of identity Issue 68 Year 3 • Josu Legarreta, Basque Director of Relations with Basque Communities. The BasqueThe archives,Basque 4 • An interview with Arantxa Arzamendi, a source of identity Director of the Basque Cultural Heritage Department 5 • The Basque archives can be consulted from any part of the planet 8 • Classification and digitalization of parish archives 9 • Gloria Totoricagüena: «Knowledge of a common historical past is essential to maintaining a people’s signs of identity» 12 • Urazandi, a project shining light on Basque emigration 14 • Basque periodicals published in Venezuela and Mexico Issue 68. Year 2005 ARTICLES 16 • The Basque "Y", a train on the move 18 • Nestor Basterretxea, sculptor. AUTHOR A return traveller Eusko Jaurlaritza-Kanpo Harremanetarako Idazkaritza 20 • Euskaditik: The Bishop of Bilbao, elected Nagusia President of the Spanish Episcopal Conference Basque Government-General 21 • Euskaditik: Election results Secretariat for Foreign Action 22 • Euskal gazteak munduan / Basque youth C/ Navarra, 2 around the world 01007 VITORIA-GASTEIZ Nestor Basterretxea Telephone: 945 01 7900 [email protected] DIRECTOR EUSKAL ETXEAK / ETXEZ ETXE Josu Legarreta Bilbao COORDINATION AND EDITORIAL 24 • Proliferation of programs in the USA OFFICE 26 • Argentina. An exhibition for the memory A. Zugasti (Kazeta5 Komunikazioa) 27 • Impressions of Argentina -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel.