Ivan Kozlenko's Novel Tanzher and the Queer Challenge to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry Sampler

POETRY SAMPLER 2020 www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature: An Anthology Edited by Maxim D. Shrayer New York Elegies: Ukrainian Poems on the City Edited by Ostap Kin Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine Edited by Oksana Maksymchuk & Max Rosochinsky The White Chalk of Days: The Contemporary Ukrainian Literature Series Anthology Compiled and edited by Mark Andryczyk www.academicstudiespress.com Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature An Anthology Edited, with Introductory Essays by Maxim D. Shrayer Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiv Note on Transliteration, Spelling of Names, and Dates xvi Note on How to Use This Anthology xviii General Introduction: The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature Maxim D. Shrayer xxi Early Voices: 1800s–1850s 1 Editor’s Introduction 1 Leyba Nevakhovich (1776–1831) 3 From Lament of the Daughter of Judah (1803) 5 Leon Mandelstam (1819–1889) 11 “The People” (1840) 13 Ruvim Kulisher (1828–1896) 16 From An Answer to the Slav (1849; pub. 1911) 18 Osip Rabinovich (1817–1869) 24 From The Penal Recruit (1859) 26 Seething Times: 1860s–1880s 37 Editor’s Introduction 37 Lev Levanda (1835–1888) 39 From Seething Times (1860s; pub. 1871–73) 42 Grigory Bogrov (1825–1885) 57 “Childhood Sufferings” from Notes of a Jew (1863; pub. 1871–73) 59 vi Table of Contents Rashel Khin (1861–1928) 70 From The Misfit (1881) 72 Semyon Nadson (1862–1887) 77 From “The Woman” (1883) 79 “I grew up shunning you, O most degraded nation . .” (1885) 80 On the Eve: 1890s–1910s 81 Editor’s Introduction 81 Ben-Ami (1854–1932) 84 Preface to Collected Stories and Sketches (1898) 86 David Aizman (1869–1922) 90 “The Countrymen” (1902) 92 Semyon Yushkevich (1868–1927) 113 From The Jews (1903) 115 Vladimir Jabotinsky (1880–1940) 124 “In Memory of Herzl” (1904) 126 Sasha Cherny (1880–1932) 130 “The Jewish Question” (1909) 132 “Judeophobes” (1909) 133 S. -

3. Ostap Bender: the King Is Born

——————————————— Ostap Bender: The King Is Born ——————————————— CHAPTER 3 OSTAP BENDER: THE KING IS BORN — 89 — —————————————————— CHAPTER THREE —————————————————— — 90 — ——————————————— Ostap Bender: The King Is Born ——————————————— Dvenadtsat’ stuliev (The Twelve Chairs, 1928) and Zolotoi telenok (The Golden Calf, 1931, Soviet book edition 1933), by Ilya Il’f and Evgenii Petrov, hold a unique place in Soviet culture. Although incorporated into the official canon of SocialistR ealist satire (a phenomenon whose very existence was constantly put into question), the books “became a pool of quotes for several generations of Soviet intellectuals, who found the diptych to be a nearly overt travesty of propagandistic formulae, newspaper slogans, and the dictums of the founders of ‘Marxism- Leninism.’ Paradoxically, this ‘Soviet literary classic’ was read as anti- Soviet literature.” (Odesskii and Feldman, 6) As Mikhail Odesskii and David Feldman (12–25) have shown, Dvenadtsat’ stuliev was commissioned to Valentin Kataev and his “brigade” in 1927 by Vladimir Narbut, editor-in-chief of the journal 30 days, which serialized the novel throughout the first half of 1928. Narbut also was a director of a major publishing house, “Zemlia i Fabrika” (“Land and Factory”), which released the novel in book form after the journal publication. Kataev, already a recognized writer, invited two young journalists into his “brigade,” his brother Petrov and Il’f—an old acquaintance from Odessa and a colleague at the newspaper Gudok (Train Whistle) where Kataev had also worked in the past—letting them develop his story of a treasure hidden inside one chair of a dining room set. However, once Kataev had ascertained that the co-authors were managing fine without a “master’s oversight,” the older brother left the group and the agreement with the journal and publisher was passed on to Il’f and Petrov. -

RUSSIAN THEATRE in the AGE of MODERNISM Also by Robert Russell

RUSSIAN THEATRE IN THE AGE OF MODERNISM Also by Robert Russell VALENTIN KATAEV V. MAYAKOVSKY, KLOP RUSSIAN DRAMA OF THE REVOLUTIONARY PERIOD YU.TRIFONOV,OBMEN Also by Andrew Barratt YURY OLESHA'S 'ENVY' BETWEEN TWO WORLDS: A CRITICAL INTRODUCTION TO THE MASTER AND MARGARITA A WICKED IRONY: THE RHETORIC OF LERMONTOV'S A HERO OF OUR TIME (with A. D. P. Briggs) Russian Theatre in the Age of Modernism Edited by ROBERT RUSSELL Senior Lecturer in Russian University of Sheffield and ANDREW BARRATT Senior Lecturer in Russian University of Otago Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-1-349-20751-0 ISBN 978-1-349-20749-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-20749-7 Editorial matter and selection © Robert Russell and Andrew Barratt 1990 Text © The Macmillan Press Ltd 1990 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1990 All rights reserved. For information, write: Scholarly and Reference Division, St. Martin's Press, Inc., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 First published in the United States of America in 1990 ISBN 978-0-312-04503-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Russian theatre in the age of modernism / edited by Robert Russell and Andrew Barratt. p. em. ISBN 978-0-312-04503-6 1. Theater-Soviet Union-History-2Oth century. I. Russell, Robert, 1946-- . II. Barratt, Andrew. PN2724.R867 1990 792' .0947'09041--dc20 89-70291 OP Contents Preface vii Notes on the Contributors xii 1 Stanislavsky's Production of Chekhov's Three Sisters Nick Worrall 1 2 Boris Geyer and Cabaretic Playwriting Laurence Senelick 33 3 Boris Pronin, Meyerhold and Cabaret: Some Connections and Reflections Michael Green 66 4 Leonid Andreyev's He Who Gets Slapped: Who Gets Slapped? Andrew Barratt 87 5 Kuzmin, Gumilev and Tsvetayeva as Neo-Romantic Playwrights Simon Karlinsky 106 6 Mortal Masks: Yevreinov's Drama in Two Acts Spencer Golub 123 7 The First Soviet Plays Robert Russell 148 8 The Nature of the Soviet Audience: Theatrical Ideology and Audience Research in the 1920s Lars Kleberg 172 9 German Expressionism and Early Soviet Drama Harold B. -

Babel' in Context a Study in Cultural Identity B O R D E R L I N E S : R U S S I a N А N D E a S T E U R O P E a N J E W I S H S T U D I E S

Babel' in Context A Study in Cultural Identity B o r d e r l i n e s : r u s s i a n а n d e a s t e u r o p e a n J e w i s h s t u d i e s Series Editor: Harriet Murav—University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Editorial board: Mikhail KrutiKov—University of Michigan alice NakhiMovsKy—Colgate University David Shneer—University of Colorado, Boulder anna ShterNsHis—University of Toronto Babel' in Context A Study in Cultural Identity Ef r a i m Sic hEr BOSTON / 2012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book as available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2012 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved Effective July 29, 2016, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. ISBN 978-1-936235-95-7 Cloth ISBN 978-1-61811-145-6 Electronic Book design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press in 2012 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com C o n t e n t s Note on References and Translations 8 Acknowledgments 9 Introduction 11 1 / Isaak Babelʹ: A Brief Life 29 2 / Reference and Interference 85 3 / Babelʹ, Bialik, and Others 108 4 / Midrash and History: A Key to the Babelesque Imagination 129 5 / A Russian Maupassant 151 6 / Babelʹ’s Civil War 170 7 / A Voyeur on a Collective Farm 208 Bibliography of Works by Babelʹ and Recommended Reading 228 Notes 252 Index 289 Illustrations Babelʹ with his father, Nikolaev 1904 32 Babelʹ with his schoolmates 33 Benia Krik (still from the film, Benia Krik, 1926) 37 S. -

Scando-Slavica Valentin Kataev's Later Writing

This article was downloaded by: [Conliffe, Mark] On: 10 May 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 922094279] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Scando-Slavica Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t716100751 Valentin Kataev's Later Writing and “Uže napisan Verter”: Time, Memory, and a Critical Dream Mark Conliffe a a Dept. of German and Russian, Willamette University, Salem, OR, USA Online publication date: 10 May 2010 To cite this Article Conliffe, Mark(2010) 'Valentin Kataev's Later Writing and “Uže napisan Verter”: Time, Memory, and a Critical Dream', Scando-Slavica, 56: 1, 7 — 26 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00806765.2010.483775 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00806765.2010.483775 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Odessa 2017 UDC 069:801 (477.74) О417 Editorial Board T

GUIDE Odessa 2017 UDC 069:801 (477.74) О417 Editorial board T. Liptuga, G. Zakipnaya, G. Semykina, A. Yavorskaya Authors A. Yavorskaya, G. Semykina, Y. Karakina, G. Zakipnaya, L. Melnichenko, A. Bozhko, L. Liputa, M. Kotelnikova, I. Savrasova English translation O. Voronina Photo Georgiy Isayev, Leonid Sidorsky, Andrei Rafael О417 Одеський літературний музей : Путівник / О. Яворська та ін. Ред. кол. : Т. Ліптуга та ін., – Фото Г. Ісаєва та ін. – Одеса, 2017. – 160 с.: іл. ISBN 978-617-7613-04-5 Odessa Literary Museum: Guide / A.Yavorskaya and others. Editorial: T. Liptuga and others, - Photo by G.Isayev and others. – Odessa, 2017. — 160 p.: Illustrated Guide to the Odessa Literary Museum is a journey of more than two centuries, from the first years of the city’s existence to our days. You will be guided by the writers who were born or lived in Odessa for a while. They created a literary legend about an amazing and unique city that came to life in the exposition of the Odessa Literary Museum UDC 069:801 (477.74) Англійською мовою ISBN 978-617-7613-04-5 © OLM, 2017 INTRODUCTION The creators of the museum considered it their goal The open-air exposition "The Garden of Sculptures" to fill the cultural lacuna artificially created by the ideo- with the adjoining "Odessa Courtyard" was a successful logical policy of the Soviet era. Despite the thirty years continuation of the main exposition of the Odessa Literary since the opening day, the exposition as a whole is quite Museum. The idea and its further implementation belongs he foundation of the Odessa Literary Museum was museum of books and local book printing and the history modern. -

A Companion to Andrei Platonov's the Foundation

A Companion to Andrei Platonov’s The Foundation Pit Studies in Russian and Slavic Literatures, Cultures and History Series Editor: Lazar Fleishman A Companion to Andrei Platonov’s The Foundation Pit Thomas Seifrid University of Southern California Boston 2009 Copyright © 2009 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-934843-57-4 Book design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press in 2009 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com iv Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE Platonov’s Life . 1 CHAPTER TWO Intellectual Influences on Platonov . 33 CHAPTER THREE The Literary Context of The Foundation Pit . 59 CHAPTER FOUR The Political Context of The Foundation Pit . 81 CHAPTER FIVE The Foundation Pit Itself . -

Slavic Lang M98T GE Form

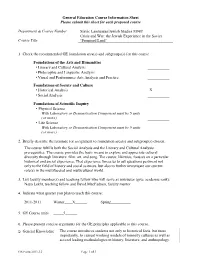

General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Slavic Languages/Jewish Studies M98T Crisis and War: the Jewish Experience in the Soviet Course Title ‘Promised Land’ 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis X • Social Analysis Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. The course fulfills both the Social Analysis and the Literary and Cultural Analysis prerequisites. The course provides the basic means to explore and appreciate cultural diversity through literature, film, art, and song. The course, likewise, focuses on a particular historical and social experience. That experience forces us to ask questions pertinent not only to the field of history and social sciences, but also to further investigate our current role(s) in the multifaceted and multicultural world. 3. List faculty member(s) and teaching fellow who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Naya Lekht, teaching fellow and David MacFadyen, faculty mentor 4. Indicate what quarter you plan to teach this course: 2011-2011 Winter____X______ Spring__________ 5. GE Course units _____5______ 6. Please present concise arguments for the GE principles applicable to this course. General Knowledge The course introduces students not only to historical facts, but more importantly, to current working models of minority cultures as well as several leading methodologies in history, literature, and anthropology. -

RUSSIAN ANTI-LITERATURE Rolf Hellebust University of Nottingham

RUSSIAN ANTI-LITERATURE Rolf Hellebust University of Nottingham The term anti-literature has a distinctly modern cachet. It was coined in 1935 by the English poet David Gascoyne, who used it to describe the maximalist avant-garde épatage of Dada and the Surrealists.1 A subtype, the anti-novel, comes to the fore in the latter half of the century with the appearance of the French nouveau roman in the 1950s and 60s. A search for literary analogues in twentieth-century Russia may fail to come up with any native Robbe- Grillet – yet the period over which Russians have been trying to write the novel to end all novel-writing has extended at least from Tolstoy‟s War and Peace (1869) to Andrei Bitov‟s Pushkin House (1978) and Sasha Sokolov‟s Palisandria (1985). No less than their Western counterparts from Cervantes to Joyce and beyond, these authors aim to exhaust the novel and/or create its ultimate representative by taking to an extreme its pre-existing tendencies: these include intertextuality and parody, fiction‟s encroachment upon non-fiction and upon historiography in particular, the sense of the novel as a genre minimally bound by literary conventions, and finally, the impression of exhaustiveness that comes from sheer length alone. To describe War and Peace as a work of anti-literature in the same breath as the postmodernist production of Bitov and Sokolov (not to mention Robbe-Grillet) may seem 1 2 anachronistic. Recall, though, Tolstoy‟s own comments on his book. Defending himself against anticipated criticism of his formal idiosyncrasies, the author of what is often considered the greatest novel ever written declares What is War and Peace? It is not a novel. -

Russian Drama in Marath I Polysystem 255

RUSSIAN DRAMA IN MARATH I POLYSYSTEM 255 Chapter VI: RUSSIAN DRAMA IN MARATHI POLYSYSTEM I A brief discussion o,n the theoretical aspect of translation of drama: Before examining the specific trends in drama translation, it is essential to place the main streams in the area of theatre translation within the framework of broader main streams in literary translation theory. It is observed that drama translation generally follows these trends. As we have already discussed in Chapter II, in the last twenty-five years there have been two major conflicting developments in the translation theory. The linguistically-oriented trend considers literary translation as a process of textual transfer. This is an ST oriented approach. In this approach translation scholars draw on recent work in descriptive linguistics. They attempt to grasp systematically the syntactic, stylistic and pragmatic properties of the texts in question. Moving away from comparative textual analysis, attempts are also made to set translations and their reception within the context of the receiving culture. This involves the study of the translations in the TL culture. The focus is not on mere textual transfer, but on cultural mediation and interchange. With regard to the first trend, Bogatyrev in discussing the function of the linguistic system in theatre in relation to the total experience states: Linguistic expression in theatre is a structure of signs constituted not only as discourse signs, but also as other signs. (Bogatyrev 1971:517-30) In a study of the specific problems of literary translation, with particular reference to the translation of dramatic texts, Susan Bassnet states that: In trying to formulate any theory of theatre translation, Bogatyrev's description of linguistic expression must be taken into account, and the 256 linguistic element must be translated bearing in mind its function in theatre discourse as a whole. -

1 / Isaak Babelʹ: a Brief Life

1 / Isaak Babelʹ: A Brief Life Beginnings Neither Babelʹ’s “Autobiography,” written in 1924 to gain ideological credentials as a “Soviet” writer, nor the so-called autobiographical stories, which Babelʹ intended to collect under the title Story of My Dovecote (История моей голубятни) strictly relate to the facts, but they are illuminating for the construction of the writer’s identity as someone who hid his highly individual personality behind the mask of a Soviet writer who had broken with his bourgeois Jewish past. Babelʹ’s father, for example, was not an impoverished shopkeeper, but a dealer in agricultural machinery, though not a particularly successful businessman. Emmanuel Itskovich, born in Belaia Tserkovʹ, was a typical merchant who had worked his way up and set up his own business.1 Babelʹ’s mother, Fenia (neé Shvekhvelʹ), as Nathalie Babel has testified, was quite unlike the Rachel of the Childhood stories. About his book of Childhood stories, Story of My Dovecote, Babelʹ wrote his family: “The subjects of the stories are all taken from my childhood, but, of course, there is much that has been made up and changed. When the book is finished, it will be clear why I had to do all that.”2 But then the fantasies of the untruthful boy in the story “In the Basement” (“В подвале”) do inject a kind of poetic truth into the real lives of his crazy grandfather, a disgraced rabbi from Belaia Tserkovʹ, and his drunken uncle Simon-Wolf. Despite the necessary post-revolutionary revision of biography carried out by many writers, nothing could be more natural than Hebrew, the Bible, and Talmud being taught at home by a melamed, or part-time tutor. -

Isaac Babel, Fellow Traveling, and the End of Nep *

The NEP Era: Soviet Russia 1921-1928, 6 (2012), 1-25. JANNEKE VAN DE STADT TWO TALES OF ONE CITY: ISAAC BABEL, FELLOW TRAVELING, AND THE END OF NEP * Abstract “An Evening at the Empress’s” (1922) and “The Road” (1932), two nar- ratives by Isaac Babel that have garnered relatively little critical attention, chart the harrowing descent of a once free-wheeling, confident NEP-era writer into the treacherous creative abyss that followed thereafter. While they have been described in passing as related variants, this study propos- es that the stories in question share a dark and much more deliberate compositional relationship. Over a span of ten years, Babel first depicts the open, independently-traveled creative road of the early twenties, and then reconfigures it to reflect its methodical narrowing, and eventual re- duction, to a vertiginous tight rope. This essay, in which the 1932 story is re-read through the revealing lens of its antecedent, examines Babel’s ret- rospective take on NEP as he witnessed, and experienced, the crippling effects of its dissolution. “The Marxian method affords an opportunity to estimate the condi- tions for the development of the new art, to trace all its sources, to help the most progressive tendencies by a critical illumination of the road, but it does not do more than that. Along its paths, art must make its own way on its own two feet.” Leon Trotsky “Journeys, like artists, are born and not made.” Lawrence Durrell In Literature and Revolution (1923), Trotsky explains that the creative disposition of Boris Pil’niak, Vsevolod Ivanov, and Sergei Esenin “has * This essay is dedicated to Judith Deutsch Kornblatt, whose keen critical eye and intel- lectual generosity have been invaluable “fellow travelers” of my work on Babel.