Isaac Babel, Fellow Traveling, and the End of Nep *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry Sampler

POETRY SAMPLER 2020 www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature: An Anthology Edited by Maxim D. Shrayer New York Elegies: Ukrainian Poems on the City Edited by Ostap Kin Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine Edited by Oksana Maksymchuk & Max Rosochinsky The White Chalk of Days: The Contemporary Ukrainian Literature Series Anthology Compiled and edited by Mark Andryczyk www.academicstudiespress.com Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature An Anthology Edited, with Introductory Essays by Maxim D. Shrayer Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiv Note on Transliteration, Spelling of Names, and Dates xvi Note on How to Use This Anthology xviii General Introduction: The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature Maxim D. Shrayer xxi Early Voices: 1800s–1850s 1 Editor’s Introduction 1 Leyba Nevakhovich (1776–1831) 3 From Lament of the Daughter of Judah (1803) 5 Leon Mandelstam (1819–1889) 11 “The People” (1840) 13 Ruvim Kulisher (1828–1896) 16 From An Answer to the Slav (1849; pub. 1911) 18 Osip Rabinovich (1817–1869) 24 From The Penal Recruit (1859) 26 Seething Times: 1860s–1880s 37 Editor’s Introduction 37 Lev Levanda (1835–1888) 39 From Seething Times (1860s; pub. 1871–73) 42 Grigory Bogrov (1825–1885) 57 “Childhood Sufferings” from Notes of a Jew (1863; pub. 1871–73) 59 vi Table of Contents Rashel Khin (1861–1928) 70 From The Misfit (1881) 72 Semyon Nadson (1862–1887) 77 From “The Woman” (1883) 79 “I grew up shunning you, O most degraded nation . .” (1885) 80 On the Eve: 1890s–1910s 81 Editor’s Introduction 81 Ben-Ami (1854–1932) 84 Preface to Collected Stories and Sketches (1898) 86 David Aizman (1869–1922) 90 “The Countrymen” (1902) 92 Semyon Yushkevich (1868–1927) 113 From The Jews (1903) 115 Vladimir Jabotinsky (1880–1940) 124 “In Memory of Herzl” (1904) 126 Sasha Cherny (1880–1932) 130 “The Jewish Question” (1909) 132 “Judeophobes” (1909) 133 S. -

Isaak Babel," Anonymous, "He Died for Art," Nesweek (July 27, 1964)

European Writers: The Twentieth Century. Ed. George Stade. Vol. 11. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1983. Pp. 1885-1914. Babel's extant output: movie scripts, early short Isaac Babel fiction, journalistic sketches, one translation, and a few later stories that remained unpublished in Babel's lifetime (they were considered offensive either to the (1894 – 1940) party line or the censor's sense of public delicacy). His most famous work, the cycle of short stories Gregory Freidin and vignettes, Konarmiia (Red Cavalry), was first published in a separate edition in 1926. It dealt with the experiences of the Russo-Polish War of 1920 as (A version of this essay in Critical Biography was seen through the bespectacled eyes of a Russian published in European Writer of the Twentieth Jewish intellectual working, as Babel himself had Century [NY: Scribners, 1990]) done, for the newspaper of the red Cossack army. This autobiographical aura played a key rôle in the success and popularity of the cycle. The thirty three jewel-like pieces, strung together to form the first Isaac Babel (1894-1940) was, perhaps, the first edition of Red Cavalry, were composed in a short Soviet prose writer to achieve a truly stellar stature in period of time, between the summer of 1923 and the Russia, to enjoy a wide-ranging international beginning of 1925, and together constitute Babel's reputation as a grand master of the short story,1 and lengthiest work of fiction (two more pieces would be to continue to influence—directly through his own added subsequently). They also represent his most work as well as through criticism and scholarship— innovative and daring technical accomplishment. -

Babel' in Context a Study in Cultural Identity B O R D E R L I N E S : R U S S I a N А N D E a S T E U R O P E a N J E W I S H S T U D I E S

Babel' in Context A Study in Cultural Identity B o r d e r l i n e s : r u s s i a n а n d e a s t e u r o p e a n J e w i s h s t u d i e s Series Editor: Harriet Murav—University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Editorial board: Mikhail KrutiKov—University of Michigan alice NakhiMovsKy—Colgate University David Shneer—University of Colorado, Boulder anna ShterNsHis—University of Toronto Babel' in Context A Study in Cultural Identity Ef r a i m Sic hEr BOSTON / 2012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book as available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2012 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved Effective July 29, 2016, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. ISBN 978-1-936235-95-7 Cloth ISBN 978-1-61811-145-6 Electronic Book design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press in 2012 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com C o n t e n t s Note on References and Translations 8 Acknowledgments 9 Introduction 11 1 / Isaak Babelʹ: A Brief Life 29 2 / Reference and Interference 85 3 / Babelʹ, Bialik, and Others 108 4 / Midrash and History: A Key to the Babelesque Imagination 129 5 / A Russian Maupassant 151 6 / Babelʹ’s Civil War 170 7 / A Voyeur on a Collective Farm 208 Bibliography of Works by Babelʹ and Recommended Reading 228 Notes 252 Index 289 Illustrations Babelʹ with his father, Nikolaev 1904 32 Babelʹ with his schoolmates 33 Benia Krik (still from the film, Benia Krik, 1926) 37 S. -

Odessa 2017 UDC 069:801 (477.74) О417 Editorial Board T

GUIDE Odessa 2017 UDC 069:801 (477.74) О417 Editorial board T. Liptuga, G. Zakipnaya, G. Semykina, A. Yavorskaya Authors A. Yavorskaya, G. Semykina, Y. Karakina, G. Zakipnaya, L. Melnichenko, A. Bozhko, L. Liputa, M. Kotelnikova, I. Savrasova English translation O. Voronina Photo Georgiy Isayev, Leonid Sidorsky, Andrei Rafael О417 Одеський літературний музей : Путівник / О. Яворська та ін. Ред. кол. : Т. Ліптуга та ін., – Фото Г. Ісаєва та ін. – Одеса, 2017. – 160 с.: іл. ISBN 978-617-7613-04-5 Odessa Literary Museum: Guide / A.Yavorskaya and others. Editorial: T. Liptuga and others, - Photo by G.Isayev and others. – Odessa, 2017. — 160 p.: Illustrated Guide to the Odessa Literary Museum is a journey of more than two centuries, from the first years of the city’s existence to our days. You will be guided by the writers who were born or lived in Odessa for a while. They created a literary legend about an amazing and unique city that came to life in the exposition of the Odessa Literary Museum UDC 069:801 (477.74) Англійською мовою ISBN 978-617-7613-04-5 © OLM, 2017 INTRODUCTION The creators of the museum considered it their goal The open-air exposition "The Garden of Sculptures" to fill the cultural lacuna artificially created by the ideo- with the adjoining "Odessa Courtyard" was a successful logical policy of the Soviet era. Despite the thirty years continuation of the main exposition of the Odessa Literary since the opening day, the exposition as a whole is quite Museum. The idea and its further implementation belongs he foundation of the Odessa Literary Museum was museum of books and local book printing and the history modern. -

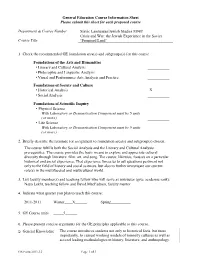

Slavic Lang M98T GE Form

General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Slavic Languages/Jewish Studies M98T Crisis and War: the Jewish Experience in the Soviet Course Title ‘Promised Land’ 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis X • Social Analysis Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. The course fulfills both the Social Analysis and the Literary and Cultural Analysis prerequisites. The course provides the basic means to explore and appreciate cultural diversity through literature, film, art, and song. The course, likewise, focuses on a particular historical and social experience. That experience forces us to ask questions pertinent not only to the field of history and social sciences, but also to further investigate our current role(s) in the multifaceted and multicultural world. 3. List faculty member(s) and teaching fellow who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Naya Lekht, teaching fellow and David MacFadyen, faculty mentor 4. Indicate what quarter you plan to teach this course: 2011-2011 Winter____X______ Spring__________ 5. GE Course units _____5______ 6. Please present concise arguments for the GE principles applicable to this course. General Knowledge The course introduces students not only to historical facts, but more importantly, to current working models of minority cultures as well as several leading methodologies in history, literature, and anthropology. -

1 / Isaak Babelʹ: a Brief Life

1 / Isaak Babelʹ: A Brief Life Beginnings Neither Babelʹ’s “Autobiography,” written in 1924 to gain ideological credentials as a “Soviet” writer, nor the so-called autobiographical stories, which Babelʹ intended to collect under the title Story of My Dovecote (История моей голубятни) strictly relate to the facts, but they are illuminating for the construction of the writer’s identity as someone who hid his highly individual personality behind the mask of a Soviet writer who had broken with his bourgeois Jewish past. Babelʹ’s father, for example, was not an impoverished shopkeeper, but a dealer in agricultural machinery, though not a particularly successful businessman. Emmanuel Itskovich, born in Belaia Tserkovʹ, was a typical merchant who had worked his way up and set up his own business.1 Babelʹ’s mother, Fenia (neé Shvekhvelʹ), as Nathalie Babel has testified, was quite unlike the Rachel of the Childhood stories. About his book of Childhood stories, Story of My Dovecote, Babelʹ wrote his family: “The subjects of the stories are all taken from my childhood, but, of course, there is much that has been made up and changed. When the book is finished, it will be clear why I had to do all that.”2 But then the fantasies of the untruthful boy in the story “In the Basement” (“В подвале”) do inject a kind of poetic truth into the real lives of his crazy grandfather, a disgraced rabbi from Belaia Tserkovʹ, and his drunken uncle Simon-Wolf. Despite the necessary post-revolutionary revision of biography carried out by many writers, nothing could be more natural than Hebrew, the Bible, and Talmud being taught at home by a melamed, or part-time tutor. -

DESCRIBE the NIGHT by Rajiv Joseph Directed by Giovanna Sardelli

Study Guide: Students & Educators DESCRIBE THE NIGHT By Rajiv Joseph Directed by Giovanna Sardelli Heather Baird Director of Education Tyler Easter Education Associate Fran Tarr Education Coordinator New York Premire Play1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I | THE PLAY Synopsis Characters Settings Themes SECTION II | THE CREATIVE TEAM Playwright & Director Biographies Cast List SECTION III | YOUR STUDENTS AS AUDIENCE Theater Vocabulary Describe the Night Vocabulary Describe the Night in Historical Context: Historical Figures: The people of Describe the Night Historical Timeline: The events that inspired Describe the Night Important Terms, Places, and Events in the world of Describe the Night Pre-Theater Activity SECTION IV | YOUR STUDENTS AS ACTORS Reading a Scene for Understanding Practical Aesthetics Exercise Mini-Lesson Vocabulary Scene Analysis Worksheet SECTION V | YOUR STUDENTS AS ARTISTS Post-Theater Creative Response Activity Common Core & DOE Theater Blueprint SECTION VI | THE ATLANTIC LEGACY Sources 2 THE PLAY THE PLAY Section I: The Play Synopsis Characters 3 SYNOPSIS In 1920, the Russian writer Isaac Babel wanders the countryside with the Red Cavalry. Seventy years later, a mysterious KGB agent spies on a woman in Dresden and falls in love. In 2010, an aircraft carrying most of the Polish government crashes in the Russian city of Smolensk. Set in Russia over the course of 90 years, this thrilling and epic new play by Rajiv Joseph (Atlantic’s Guards at the Taj, Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo) traces the stories of seven men and women con- nected by history, myth and conspiracy theories. *Denotes an actual historical figure CHARACTERS *Isaac - Russian, Jewish. -

Gregory Freidin Curriculum Vitae

GREGORY FREIDIN CURRICULUM VITAE Department of Slavic Languages & Literatures Stanford University Stanford CA 94305-2006 Phone: (650) 725-0006 / (650) 723-4438; Fax: (650) 723-0011 Email: [email protected] Education Ph.D., Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of California at Berkeley, June, 1979. Dissertation: "Time, Identity and Myth in Osip Mandelstam: 1908-1921" M.A., Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of California at Berkeley, June 1974 Special Student, Brandeis University, 1972 The First State Institute of Foreign Languages, Moscow, USSR, 1969-1971 Secondary School, Moscow, USSR, 1964 Professional Experience Director, Interdisciplinary Studies in the Humanities, Stanford University, April 2007- Interim Head, Division of Literatures, Cultures, and Languages (DLCL), 2005-2006 Research Fellow, European Forum at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, 2005- Acting Director, Center for Russian East-European and Eurasian Studies. Stanford University. 2003-04 Chairman, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, Stanford University, 1994-97, 1998-2001, 2007- Visiting Professor, Department of Slavic Languages & Literatures, University of California at Berkeley, 2001 Professor, 1993- Associate Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, Stanford University, 1985-93 Assistant Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, Stanford University 1978-85 Visiting Lecturer, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, Stanford University, 1977-78 -

O'donnell 1 the Soviet Century, 1914-2000 New York University

The Soviet Century, 1914-2000 New York University, Spring 2018 CORE UA-528 T/Th 3:30 – 4:45 PM Silver 408 Professor Anne O'Donnell Office hours: T 12:30-1:30 PM 19 University Place, Room 216 [email protected] Course Description: By its own definition, the Soviet Union was neither nation-state nor empire, neither capitalist nor communist, neither east nor west. What was the Soviet Union? What was Soviet socialism? Who made it? What was the role of the Communist Party in creating and maintaining Soviet rule? What is a personal dictatorship, and how did the Soviet Union become one? How did the Soviet regime maintain its rule over one-sixth the world’s landmass? Did it enjoy legitimacy among the population, and if so, why? What was the role of violence or coercion in the maintenance of Soviet power? Did people “believe” in the Soviet Union, and if so, in what exactly? How did the Soviet regime use institutions, social class, information networks, consumer desires, ethnic minorities, expert knowledge, cultural production, and understandings of the non-Soviet outside world to advance its ambitions? How and why did it succeed or fail? In the wake of recent challenges to liberal institutions across the Western world, the history of the Soviet Union offers its students critical insight into the characteristics and functioning of illiberal politics and an unfree society. It also illuminates the experience of people who made and lived through the world’s greatest experiment in organizing a non-capitalist society. This course will examine the project of building socialism—as a culture, economy, and polity—in the Soviet Union and its satellites from inception to collapse. -

Ivan Kozlenko's Novel Tanzher and the Queer Challenge to The

31 In Search of Territories of Freedom: Ivan Kozlenko’s Novel Tanzher and the Queer Challenge to the Ukrainian Canon Vitaly Chernetsky Abstract: Ivan Kozlenko’s novel Tanzher (Tangier) became one of Ukraine’s biggest cultural events of 2017, vigorously debated in the country’s media and shortlisted for multiple prizes. This was unprecedented for Ukrainian literatu- re: a queer-themed novel whose plot centers on two pansexual love triangles, one taking place in the 1920s, the other in the early 2000s, did not provoke a torrent of homophobic abuse. Its presentations were not picketed by right- -wing extremists, the way this happened on multiple occasions to other recent gay-themed publications, most notably the 2009 anthology 120 storinok So- domu (120 Pages of Sodom). Set in the city of Odessa, the novel constructs an alternative affirming myth, reinterpreting the episode in the city’s history when it served as Ukraine’s capital of filmmaking in the 1920s and seeking to reinsert this queer-positive narrative into the national literary canon. This article analyzes the project of utopian transgression the novel seeks to enact and situates it both in the domestic sociocultural field and in the broader con- texts of global LGBTQ writing, countercultural practices, and the challenges faced by postcommunist societies struggling with the new conservative turn in national cultural politics. Keywords: Ukrainian literature; Odessa; queering the canon; postmodernist intertextuality; pansexuality In recent years, discussions of Ukrainian culture often sought to combine two seemingly opposite trends: an emphasis on unity, in the face of attempts at fracturing the nation along political, regional, generational, linguistic, and other lines, and the thesis that its diversity can be seen as a source of its strength. -

Checklist of the Works of Isaak Babel΄ (1894-1940) and Translations Compiled by Efraim Sicher Ben-Gurion University of the Nege

Checklist of the works of Isaak Babel΄ (1894-1940) and translations Compiled by Efraim Sicher Ben-Gurion University of the Negev This bibliography of the works of Isaak Babel΄ attempts to present as complete a corpus as possible of what remains in print or in archival manuscripts. At the time of his arrest in May 1939, manuscripts were seized by the secret police and have not been traced; a new collection of stories, Новые Рассказы, was planned for publication by Советский писатель in a printrun of 20,000 copies. The conditions in which Babel΄ wrote and his own mischevious dealings with editors plus the censorship during his life and after his death in the Soviet Union and elsewhere resulted in the distortion or suppression of the true publication history and conception of his work. Even after the posthumous rehabilitation in 1954, it cost Ehrenburg much effort to have a selected works published, and following the arrest of Siniavksy in 1965, the editor of the somewhat enlarged 1966 selected works had to admit it was not easy to write about Babel΄. A slightly larger selection was published the same year in Kemerovo, instead of Odessa, as planned, because of fear that it would give the impression of an independent Odessa Jewish voice. Despite the publication of new material in various central Asian journals, all uncensored editions of the Red Cavalry stories (that is, up to 1931 inclusively) were still on the list of banned books in the USSR in 1973. The uncensored stories were published abroad, in 1979 and 1989. Perestroika eased some restrictions and new collections were published in Moscow from 1989, though there was some opposition; only at the end of the Soviet period did a collected works appear. -

How Things Were Done in Odessa

NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH TITLE: HOW THINGS WERE DONE IN ODESSA: CULTURAL AND INTELLECTUAL PURSUITS IN A SOVIET CITY OF THE 1970s AUTHOR: Maurice Friedberg University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign This report is based upon research supported in part by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research with funds provided by the U. S. Departments of State and Defense and the Central Intelligence Agency, through the Council's Contract #701 with the University of Illinois for the Soviet Interview Project. Subsequent to the expiration of federal support and the Council's Contract #701, the author has volunteered this report to the Council for distribution within the U.S. Government, By agreement with the Department of State, the costs of duplication and distribution are covered by the Council under its Grant #1006-555009 from the Department under Title VIII. The analysis and interpretations in this report are those of the author, and not of the Council or any part of the U. S. Government. DATE: May, 1989 Contents Preface I . Introduction 1 I. Ethnicity 6 II. Religion 22 III. Newspapers, Radio, Television 30 IV. Doctors and Lawyers 40 V. Educational Institutions 49 (A Music School, 53; A Theater School, 55; A School for Cooks, 56; A Boarding School, 58; Foreign Language Courses, 65; Public Schools, 67; Higher Education, 68.) VI. Entertainment 84 (A Municipal Park, 86; Organizing a Parade, 92; Sports, Chess, 96; Organized Excursions, 99; Amateur Ensembles, 100.) VII. The Arts 119 (Theater, 119; Cinema, 128; Music, 134; Painting and Sculpture, 150.) VIII.