Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice in the District of Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tazjrri ADDITIONAL HCF4ES NEEDED- We N.W.—Very Substantial Row Rd.)—Spacious Bpring 4-7453

THE EVENING STAR t APTS. UNFURN.—MD. (Coat.) APTS. UNFURNISHED—MD. |APTS. UNFURN.—VA. <C««it.> (HOUSES UNFURNISHED (Cent.) HOUSES for SALE—N.W. (Cont. > HOUStS FOR SALE—N.W. Washington, D. C. A-16 SILVER SPRING—I and 2 bedrm,. HARBOR TERRACE APARTMENTS COLORED—TAYLOR NR. 3RD ST. OVERLOOK* ROCK CREEK PARK— Excellent Terms to MONDAY. MAY30. 13.. S j (4 and 5 large rooms). Newly If you are interested In an apt con- N.W’.—6 rooms, fas heat, finished Beautiful aulet street of magnifi- - decorated. SBS 50 to §98.50. incl. venient to National Airport, we bsmt.. built-in garage: conven. cent homes bordering the park and I utils. HE. 4-7014. —5 2-BEDROOM have newly redecorated. 1-bedroom; transp : public, parochial schools; iust a few minutes from downtown. Responsible Purchaser Am. (Cent.) apts. p*r Handsome white brk.. New Orleans N.W. location nr. Walter Reed. Det. UNFUHN—P.c. SILVER SPRING—NewIy dec.: conv from $70.75 to $75.75 SIOO. Call 10 to 4. V. D. JOHN- bathe, location; bedrm- liv. dinette, mo., incl. utils. For inspection, appiy Nwd 1 STON, HU. 3-4615. —3l Colonial superb Quality Year- brick. 4 bedrmg., 2 rec. rm.. 1 rm.. HOMES i of det. brick gar. TA. kit. and bath: $75.80 mo. JU. at Apt. 1, 1301 Abingdon drive. 'round air-conditioning, library and Eves.. 9-1699 9-3490; after 6. LO 5-4800. —2 Alexandria. ¦¦¦¦¦¦¦¦ HOUSES WANTED TO RENT lavatory on Ist floor: four twin- or TU. 2-6194. DE LI'XE 2 BEDROOM APIS . -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School -

Suburbanization Historic Context and Survey Methodology

INTRODUCTION The geographical area for this project is Maryland’s 42-mile section of the I-95/I- 495 Capital Beltway. The historic context was developed for applicability in the broad area encompassed within the Beltway. The survey of historic resources was applied to a more limited corridor along I-495, where resources abutting the Beltway ranged from neighborhoods of simple Cape Cods to large-scale Colonial Revival neighborhoods. The process of preparing this Suburbanization Context consisted of: • conducting an initial reconnaissance survey to establish the extant resources in the project area; • developing a history of suburbanization, including a study of community design in the suburbs and building patterns within them; • defining and delineating anticipated suburban property types; • developing a framework for evaluating their significance; • proposing a survey methodology tailored to these property types; • and conducting a survey and National Register evaluation of resources within the limited corridor along I-495. The historic context was planned and executed according to the following goals: • to briefly cover the trends which influenced suburbanization throughout the United States and to illustrate examples which highlight the trends; • to present more detail in statewide trends, which focused on Baltimore as the primary area of earliest and typical suburban growth within the state; • and, to focus at a more detailed level on the local suburbanization development trends in the Washington, D.C. suburbs, particularly the Maryland counties of Montgomery and Prince George’s. Although related to transportation routes such as railroad lines, trolley lines, and highways and freeways, the location and layout of Washington’s suburbs were influenced by the special nature of the Capital city and its dependence on a growing bureaucracy and not the typical urban industrial base. -

Housing in the Nation's Capital

Housing in the Nation’s2005 Capital Foreword . 2 About the Authors. 4 Acknowledgments. 4 Executive Summary . 5 Introduction. 12 Chapter 1 City Revitalization and Regional Context . 15 Chapter 2 Contrasts Across the District’s Neighborhoods . 20 Chapter 3 Homeownership Out of Reach. 29 Chapter 4 Narrowing Rental Options. 35 Chapter 5 Closing the Gap . 43 Endnotes . 53 References . 56 Appendices . 57 Prepared for the Fannie Mae Foundation by the Urban Institute Margery Austin Turner G. Thomas Kingsley Kathryn L. S. Pettit Jessica Cigna Michael Eiseman HOUSING IN THE NATION’S CAPITAL 2005 Foreword Last year’s Housing in the Nation’s Capital These trends provide cause for celebration. adopted a regional perspective to illuminate the The District stands at the center of what is housing affordability challenges confronting arguably the nation’s strongest regional econ- Washington, D.C. The report showed that the omy, and the city’s housing market is sizzling. region’s strong but geographically unbalanced But these facts mask a much more somber growth is fueling sprawl, degrading the envi- reality, one of mounting hardship and declining ronment, and — most ominously — straining opportunity for many District families. Home the capacity of working families to find homes price escalation is squeezing families — espe- they can afford. The report provided a portrait cially minority and working families — out of of a region under stress, struggling against the city’s housing market. Between 2000 and forces with the potential to do real harm to 2003, the share of minority home buyers in the the quality of life throughout the Washington District fell from 43 percent to 37 percent. -

DC Kids Count E-Databook

DC ACTION FOR CHILDREN DC KIDS COUNT e-Databook “People I meet... the effect upon me of my early life... of the ward and city I live in... of the nation” —Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass Every city has many identities, depending on But Washington, aka DC, is also simply a who you ask. A legislator, a police officer, a hometown, where many people live their daily coach or a clerk might describe the same lives, raise their children and create community city’s people, culture and reputation in starkly and the future together. different terms. Washington is home to 100,000 children We are the nation’s capital, the official under 18. They are one in six DC residents. Washington that so many politicians run The number of children under the age of 5 has campaigns against. We are an international started to grow again after almost a decade of center of power, featuring stately embassies and decline.1 serving as the temporary home to diplomats. This DC KIDS COUNT e-databook is for and For some Americans, Washington is a code about them. word for the bubble where politicians hobnob with “fat cats,” bureaucrats operate and media Why Place Matters in the Lives of swarm over the latest scandal. Children (and Families) For some Americans, Washington is a place to Children grow up (and families live) in specific visit with their children to learn about history, places: neighborhoods. How well these read the original Declaration of Independence, neighborhoods are doing affects how well the stand on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and children and their families who live in them are 1. -

Line Name Routes Per Line Benning Road-H Street X2 DC Garfield

Routes per Line Name Line Jurisdicti on Benning Road-H Street X2 DC Garfield-Anacostia Loop W6,8 DC East Capitol Street-Cardozo 96,97 DC Connecticut Avenue L1,2 DC Brookland-Fort Lincoln H6 DC Crosstown H2,3,4 DC Fort Totten-Petworth 60,64 DC Benning Heights-Alabama Ave V7,8 DC Hospital Center D8 DC Glover Park-Dupont Circle D2 DC 14th Street 52,54 DC Sibley Hospital - Stadium-Armory D6 DC Ivy City-Franklin Square D4 DC Takoma-Petworth 62,63 DC Massachusetts Avenue N2,4,6 DC Military Road-Crosstown E4 DC Sheriff Road-River Terrace U4 DC Ivy City-Fort Totten E2 DC Mount Pleasant 42,43 DC North Capitol Street 80 DC P Street-LeDroit Park G2 DC Park Road-Brookland H8,9 DC Pennsylvania Avenue 32,34,36 DC Deanwood-Alabama Avenue W4 DC Wisconsin Avenue 31,33 DC Rhode Island Avenue G8 DC Georgia Avenue Limited 79 DC 16th Street S2,4 DC Friendship Heights-Southeast 30N,30S DC Georgia Avenue-7th Street 70 DC Convention Center-Southwest Waterfront 74 DC U Street-Garfield 90,92 DC Capitol Heights-Minnesota Ave V2,4 DC Deanwood-Minnesota Ave Sta U7 DC Mayfair-Marshall Heights U5,6 DC Bladensburg Road-Anacostia B2 DC United Medical Center-Anacostia W2,3 DC Anacostia-Eckington P6 DC Anacostia-Congress Heights A2,6,7,8 DC Anacostia-Fort Drum A4,W5 DC National Harbor-Southern Ave NH1 MD Annapolis Road T18 MD Greenbelt-Twinbrook C2,4 MD Bethesda-Silver Spring J1,2 MD National Harbor-Alexandria NH2 MD Chillum Road F1,2 MD District Heights-Seat Pleasant V14 MD Eastover-Addison Road P12 MD Forestville K12 MD Georgia Avenue-Maryland Y2,7,8 MD Marlboro Pike J12 MD Marlow Heights-Temple Hills H11,12,13 MD College Park 83,83X,86 MD New Hampshire Avenue-Maryland K6 MD Martin Luther King Jr. -

State of Washington, D.C.'S Neighborhoods A-3

State of Washington, D.C.’s Neighborhoods Prepared by Peter A. Tatian G. Thomas Kingsley Margery Austin Turner Jennifer Comey Randy Rosso Prepared for The Office of Planning The Government of the District of Columbia September 30, 2008 The Urban Institute 2100 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 UI project no. 08040-000-01 State of Washington, D.C.’s Neighborhoods ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................... ii Acknowledgments............................................................................................. vi About this Report ............................................................................................... 1 I. Introduction...................................................................................................... 3 II. Demographics................................................................................................. 9 Population......................................................................................................................9 Households..................................................................................................................13 III. Economy – Jobs and Income ..................................................................... 15 Employed Residents and Unemployment Rate...........................................................15 Poverty and Household Income ..................................................................................18 Public Assistance -

Neighborhood Cluster (NC)

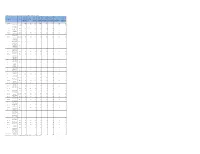

2014 Population Projections and Growth (between 2014 to 2020) by Neighborhood Cluster Office of Office of Office of % change in projected % change in projected % change in projected % change in projected Office of Planning's Planning's Planning's Planning's number of 0-3 year number of number of number of 14-17 year Neighborhood Cluster Population Cluster Names Ward Population Population Population olds per 4-10 year olds per 11-13 year olds per olds per (NC) Forecast in 2014 Forecast in 2014 Forecast in 2014 Forecast in 2014 neighborhood cluster neighborhood cluster neighborhood cluster neighborhood cluster (Ages 4-10) (Ages 0-3) (Ages 11-13) (Ages 14-17) 2014_2020 2014_2020 2014_2020 2014_2020 Citywide 36,910 44,227 15,577 20,296 12% 47% 32% 12% Kalorama Heights, Cluster 1 Adams Morgan and Ward1 & 2 981 752 179 181 18% 136% 98% 50% Columbia Heights, Mt. Pleasant, Pleasant Cluster 2 Plains and Park View Ward 1 3,506 3,267 1,044 1,251 -1% 78% 45% 27% Howard University, Le Droit Park and Cluster 3 Cardozo/Shaw Ward 1,2 & 6 565 478 116 167 32% 120% 102% 6% Georgetown and Cluster 4 Burleith/Hillandale Ward 2 650 919 243 262 89% 39% 72% 47% West End, Foggy Cluster 5 Bottom, GWU Ward 2 350 213 30 23 161% 212% 207% 158% Dupont Circle and Connecticut Avenue/K Cluster 6 Street Ward 1 & 2 608 428 71 81 55% 169% 167% 65% Cluster 7 Shaw and Logan Circle Ward 2 & 6 958 890 262 316 15% 90% 58% 27% Downtown, Chinatown, Penn Quarters, Mount Vernon Square and Cluster 8 North Capitol Street Ward 2 & 6 876 967 300 371 24% 66% 66% 30% Southwest Employment -

Report of Contracting Activity

Vendor Name Address Vendor Contact Vendor Phone Email Address Total Amount 1213 U STREET LLC /T/A BEN'S 1213 U ST., NW WASHINGTON DC 20009 VIRGINIA ALI 202-667-909 $3,181.75 350 ROCKWOOD DRIVE SOUTHINGTON CT 13TH JUROR, LLC 6489 REGINALD F. ALLARD, JR. 860-621-1013 $7,675.00 1417 N STREET NWCOOPERATIVE 1417 N ST NW COOPERATIVE WASHINGTON DC 20005 SILVIA SALAZAR 202-412-3244 $156,751.68 1133 15TH STREET NW, 12TH FL12TH FLOOR 1776 CAMPUS, INC. WASHINGTON DC 20005 BRITTANY HEYD 703-597-5237 [email protected] $200,000.00 6230 3rd Street NWSuite 2 Washington DC 1919 Calvert Street LLC 20011 Cheryl Davis 202-722-7423 $1,740,577.50 4606 16TH STREET, NW WASHINGTON DC 19TH STREET BAPTIST CHRUCH 20011 ROBIN SMITH 202-829-2773 $3,200.00 2013 H ST NWSTE 300 WASHINGTON DC 2013 HOLDINGS, INC 20006 NANCY SOUTHERS 202-454-1220 $5,000.00 3900 MILITARY ROAD NW WASHINGTON DC 202 COMMUNICATIONS INC. 20015 MIKE HEFFNER 202-244-8700 [email protected] $31,169.00 1010 NW 52ND TERRACEPO BOX 8593 TOPEAK 20-20 CAPTIONING & REPORTING KS 66608 JEANETTE CHRISTIAN 785-286-2730 [email protected] $3,120.00 21C3 LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT LL 11 WATERFORD CIRCLE HAMPTON VA 23666 KIPP ROGERS 757-503-5559 [email protected] $9,500.00 1816 12TH STREET NW WASHINGTON DC 21ST CENTURY SCHOOL FUND 20009 MARY FILARDO 202-745-3745 [email protected] $303,200.00 1550 CATON CENTER DRIVE, 21ST CENTURY SECURITY, LLC #ADBA/PROSHRED SECURITY BALTIMORE MD C. MARTIN FISHER 410-242-9224 $14,326.25 22 Atlantic Street CoOp 22 Atlantic Street SE Washington DC 20032 LaVerne Grant 202-409-1813 $2,899,682.00 11701 BOWMAN GREEN DRIVE RESTON VA 2228 MLK LLC 20190 CHRIS GAELER 703-581-6109 $218,182.28 1651 Old Meadow RoadSuite 305 McLean VA 2321 4th Street LLC 22102 Jim Edmondson 703-893-303 $13,612,478.00 722 12TH STREET NWFLOOR 3 WASHINGTON 270 STRATEGIES INC DC 20005 LENORA HANKS 312-618-1614 [email protected] $60,000.00 2ND LOGIC, LLC 10405 OVERGATE PLACE POTOMAC MD 20854 REZA SAFAMEJAD 202-827-7420 [email protected] $58,500.00 3119 Martin Luther King Jr. -

D.C.'S Disconnect Between Citywide Enrollment

D.C.’S DISCONNECT BETWEEN CITYWIDE ENROLLMENT GROWTH AND NEIGHBORHOOD CHANGES CHELSEA COFFIN | AUGUST 26, 2019 The District of Columbia has become a more popular place to live, especially for families. Population growth began in 2006, with young adults between the ages of 20 and 34 driving much of this growth (see Figure 1). This growth in the number of young adults translated into an increase in the number of babies born per year starting in 2006, and an increase in the school-age population starting in 2012. Figure 1. Population change driven by young adults and higher levels of births The school-age population (aged 5 to 17) started to rise a few years later in 2012, growing by 9 percent from 2010 to 2017.1 Public school2 enrollment for pre-kindergarten to grade 12 likewise grew by 20 percent over this time period. This population growth has also led to increased demand for family housing3 and rising property values: Citywide, the total assessed real value of single-family homes4 increased by 8.7 percent from 2010 to 2018, even while the total number of these homes decreased by 2.8 percent.5 1 Coffin, C. 2018. Will Children of Current Millennials Become Future Public School Students? D.C. Policy Center. Available at: https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/future-public-school-students-report/ 2 Here and throughout, public schools refer to both traditional public and public charter schools. 3 However, there is a lack of single-family apartments in D.C. See Tatian, P. A. and Hendley, L. 2019. -

COVID-19: Medstar Health Community Vaccine Locations

COVID-19: MedStar Health Community Vaccine Locations MedStar Health at Lafayette Centre Community Vaccination Center: MedStar Health Orthopaedic and Sports Center 1120 20th St., NW Bldg. 1 South – A Level Washington, DC 20036 See MedStar Health associate at front desk for check in instructions MedStar Health at Lafayette Centre is conveniently located in downtown Washington, D.C., midway between Dupont Circle and the K Street corridor. To access via Metro • Red Line o Dupont Circle Metro Station (0.17 miles) o Farragut North Metro Station (0.39 miles) • Orange, Silver, Blue o Farragut West Metro Station (0.49 miles) o Foggy Bottom – GWU (0.30 miles) Driving Directions Addresses listed above. Parking Garage Entrance is on 20th and 21st Street • From Northern Virginia o Take 66 East and take the E Street Exit o Turn Left onto 20th St, NW • From Bethesda / Chevy Chase o Take MD-355 South/Wisconsin Avenue toward Massachusetts Avenue o Turn right onto 21st St, NW • From Northern Prince Georges County o Take the Baltimore-Washington Pkwy in Greenbelt o Merge onto US-50 West/New York Ave NE to Rhode Island Avenue NW o Turn right onto M St, NW and turn right onto 20th Street, NW Bus Routes o MetroExtra Route (S9) o Metrobus Local Route (blue) L1, L2, D2, D6, G2, N2, N4, N3, N6 o Metrobus Major Route (red) 30N, 30S, 31, 33, 36, 38B, 42, 43, o Metrobus Commuter Route (silver) H1 MedStar Georgetown University Hospital Community Vaccination Center: Martin Marietta Conference Room 3800 Reservoir Rd., NW Lombardi Lower Level Washington, DC 20007 Driving Directions • From Northwest Washington o Take Wisconsin Avenue south to Reservoir Road. -

State of Washington, D.C.'S Neighborhoods, 2010

2010 Prepared by Jennifer Comey Chris Narducci Peter A. Tatian Prepared for The Office of Planning The Government of the District of Columbia November 2010 The Urban Institute 2100 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 Copyright © November 2010. The Urban Institute. All rights reserved. Except for short quotes, no part of this report may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the Urban Institute. The Urban Institute is a nonprofit, nonpartisan policy research and educational organization that examines the social, economic, and governance problems facing the nation. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. State of Washington, D.C.’s Neighborhoods iii CONTENTS About this Report ............................................................................................... 1 I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 5 II. Demographics ................................................................................................. 7 Population ................................................................................................................... 7 Households ................................................................................................................12 III. Economy—Jobs and Income .....................................................................