Suburbanization Historic Context and Survey Methodology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANS Annual Report 2018

i AUDUBON NATURALIST SOCIETY Annual Report: A Year In Review 2017-2018 1 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Greetings! I’m Scott Fosler, President of the Audubon Naturalist Society Board of Directors. It’s my pleasure to share with you highlights of a remarkable year for ANS. Our Education Program served the largest number of campers and had the strongest revenue outcome for summer camp in ANS history. It helped 3,500 youngsters plant and grow organic salad greens in regional public schools (200 more students than last year). Our new chemistry curriculum on water quality and nitrate pollution was rolled out to high school teachers, thanks to support from the National Park Foundation. ANS staff helped produce our first parent guide to connect children with nature, and it was featured on NBC Washington News Channel 4. Registrations for adults to explore natural areas around Washington reached nearly 2,000. In Conservation Advocacy, ANS worked for greater transparency in stormwater management, and for a final stormwater funding compromise, during a fractious battle between the Montgomery County Council and Executive. Our Creek Critters program surpassed the 10,000-users mark. And we continued our valiant work along the Route 1 Corridor in Northern Virginia. We’ve earned the trust of residents by working with faith communities to educate, train and involve them in advocating for community-oriented green infrastructure solutions to redevelopment. Scott Fosler The new deer fence is now up and already helping native plant communities flourish in Woodend Nature ANS Board President Sanctuary. Restoration plantings included 217 new native shrubs and trees. -

Olympic Rowing Regatta Beijing, China 9-17 August

2008 Olympic Rowing Regatta Beijing, China 9-17 August MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTEnts 1. Introduction 3 2. FISA 5 2.1. What is FISA? 5 2.2. FISA contacts 6 3. Rowing at the Olympics 7 3.1. History 7 3.2. Olympic boat classes 7 3.3. How to Row 9 3.4. A Short Glossary of Rowing Terms 10 3.5. Key Rowing References 11 4. Olympic Rowing Regatta 2008 13 4.1. Olympic Qualified Boats 13 4.2. Olympic Competition Description 14 5. Athletes 16 5.1. Top 10 16 5.2. Olympic Profiles 18 6. Historical Results: Olympic Games 27 6.1. Olympic Games 1900-2004 27 7. Historical Results: World Rowing Championships 38 7.1. World Rowing Championships 2001-2003, 2005-2007 (current Olympic boat classes) 38 8. Historical Results: Rowing World Cup Results 2005-2008 44 8.1. Current Olympic boat classes 44 9. Statistics 54 9.1. Olympic Games 54 9.1.1. All Time NOC Medal Table 54 9.1.2. All Time Olympic Multi Medallists 55 9.1.3. All Time NOC Medal Table per event (current Olympic boat classes only) 58 9.2. World Rowing Championships 63 9.2.1. All Time NF Medal Table 63 9.2.2. All Time NF Medal Table per event 64 9.3. Rowing World Cup 2005-2008 70 9.3.1. Rowing World Cup Medal Tables per year 2005-2008 70 9.3.2. All Time Rowing World Cup Medal Tables per event 2005-2008 (current Olympic boat classes) 72 9.4. -

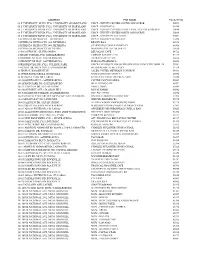

FSE Permit Numbers by Address

ADDRESS FSE NAME FACILITY ID 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER SOUTH CONCOURSE 50891 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - FOOTNOTES 55245 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER EVENT LEVEL STANDS & PRESS P 50888 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER NORTH CONCOURSE 50890 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY PLAZA LEVEL 50892 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, -, BETHESDA HYATT REGENCY BETHESDA 53242 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, 000, BETHESDA BROWN BAG 66933 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, 000, BETHESDA STARBUCKS COFFEE COMPANY 66506 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, BETHESDA MORTON'S THE STEAK HOUSE 50528 1 DISCOVERY PL, SILVER SPRING DELGADOS CAFÉ 64722 1 GRAND CORNER AVE, GAITHERSBURG CORNER BAKERY #120 52127 1 MEDIMMUNE WAY, GAITHERSBURG ASTRAZENECA CAFÉ 66652 1 MEDIMMUNE WAY, GAITHERSBURG FLIK@ASTRAZENECA 66653 1 PRESIDENTIAL DR, FY21, COLLEGE PARK UMCP-UNIVERSITY HOUSE PRESIDENT'S EVENT CTR COMPLEX 57082 1 SCHOOL DR, MCPS COV, GAITHERSBURG FIELDS ROAD ELEMENTARY 54538 10 HIGH ST, BROOKEVILLE SALEM UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 54491 10 UPPER ROCK CIRCLE, ROCKVILLE MOM'S ORGANIC MARKET 65996 10 WATKINS PARK DR, LARGO KENTUCKY FRIED CHICKEN #5296 50348 100 BOARDWALK PL, GAITHERSBURG COPPER CANYON GRILL 55889 100 EDISON PARK DR, GAITHERSBURG WELL BEING CAFÉ 64892 100 LEXINGTON DR, SILVER SPRING SWEET FROG 65889 100 MONUMENT AVE, CD, OXON HILL ROYAL FARMS 66642 100 PARAMOUNT PARK DR, GAITHERSBURG HOT POT HERO 66974 100 TSCHIFFELY -

HOPE PRESSKIT.Pdf

H.O.P.E. What You Eat Matters A Film by Nina Messinger Documentary. Austria 2017. Running Time: 92 minutes. Language: English (with subtitles). Frame Rate: 25 fps. Shooting Format: HD. Sound: Dolby Digital 5.1, Stereo 2.0. www.hope-theproject.com H.O.P.E. What You Eat Matters I Press Kit SYNOPSIS (short) Obesity, allergies, diabetes, heart disease, or cancer: More than half of all people living in the industrialized world suffer from chronic diseases. Animals are reared for our consumption under abysmal conditions. Industrial-size livestock breeding facilities contribute to world hunger and the destruction of our natural environment and climate. The documentary H.O.P.E. shows how simply changing what we put on our plates and moving towards a plant-based diet can restore our body´s health and our planet´s balance. It has a clear message: By changing our eating habits, we can change the world! (long) Half of the population in Western society suffers from being overweight. Cardio- vascular diseases, diabetes and cancer are epidemic. Our meat consumption has quintupled over the past 50 years. 65 billion land animals are being slaughtered every year for food consumption. One third of the global grain production is fed to animals for fattening while 1.8 billion people worldwide suffer from hunger and starvation. Can there really be a solution to all these problems? It was the search for an answer to this question that led Austrian author and filmmaker Nina Messinger on a journey through Europe, India and the US to investigate the consequences of our diet and to meet with leading experts in nutrition, medicine, science, and agriculture, as well as with farmers and people who have recovered from severe illnesses by simply changing their eating habits. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 117 230 Relating to Racism, Blacks

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 117 230 ID015 623 TITLE A Selected Annotated Bibliography of .Material Relating to Racism, Blacks, Chicanos, Native Americans and Multi-Ethnicity. Vol-. 2. INSTITUTION Michigan Education Association, East Lansing. iv.'of Minority Affairs. PUB DATE 73 , NOTE 105p.; For volumes 1, 3, and 4; see ED 069 445, VD 015 624 and UD 015 718 respectively EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$5.70 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; *American Indians; *Annotated Bibliographies; Cultural Background; Cultural Factors; Ethnic'Groups; Ethnic Origins;, Ethnic Status Films; .Filmstrips; Instructional MaterialsC*Mexican Americans; *Negroes; Negro fiistory; Race'Relations; Racial Discrimination; Racial Factors; *Racism; Tape Recordings IDENTIFIERS Third World ABSTRACT The' second in the series, this selected annotated hihliography deals with new and recently discovered materials that address racism, BlackS, Chicanos,'native Americans, and multi - ethnicity. This bibliography is considered to be not all . inclusive but to reflect only on that material which,is considered to be most representative of the realities that relate to the involvemeiA and contributions of Third World groupS in'the development of the United States, and the climate of the times during which such involvement and contributions ocdurred.,Listing of materials usable at the elementary level are increased over those in Volume I. Contents deal with racism, including printed.materials, film, filmstrips, records and tapes; Black materials, including printed matter, films and filmstrips; Latino materials, including printed matter, films and filmstrips; native American materials, k. including printed matter, films and filmstrips; 'and multi-ethnic printed material. A list of Third World publishers is included. , (Author/AM) ********************************************************************* Documents acquired by ERIC include,many .informal Unpublished * materials not available from other sources. -

Tazjrri ADDITIONAL HCF4ES NEEDED- We N.W.—Very Substantial Row Rd.)—Spacious Bpring 4-7453

THE EVENING STAR t APTS. UNFURN.—MD. (Coat.) APTS. UNFURNISHED—MD. |APTS. UNFURN.—VA. <C««it.> (HOUSES UNFURNISHED (Cent.) HOUSES for SALE—N.W. (Cont. > HOUStS FOR SALE—N.W. Washington, D. C. A-16 SILVER SPRING—I and 2 bedrm,. HARBOR TERRACE APARTMENTS COLORED—TAYLOR NR. 3RD ST. OVERLOOK* ROCK CREEK PARK— Excellent Terms to MONDAY. MAY30. 13.. S j (4 and 5 large rooms). Newly If you are interested In an apt con- N.W’.—6 rooms, fas heat, finished Beautiful aulet street of magnifi- - decorated. SBS 50 to §98.50. incl. venient to National Airport, we bsmt.. built-in garage: conven. cent homes bordering the park and I utils. HE. 4-7014. —5 2-BEDROOM have newly redecorated. 1-bedroom; transp : public, parochial schools; iust a few minutes from downtown. Responsible Purchaser Am. (Cent.) apts. p*r Handsome white brk.. New Orleans N.W. location nr. Walter Reed. Det. UNFUHN—P.c. SILVER SPRING—NewIy dec.: conv from $70.75 to $75.75 SIOO. Call 10 to 4. V. D. JOHN- bathe, location; bedrm- liv. dinette, mo., incl. utils. For inspection, appiy Nwd 1 STON, HU. 3-4615. —3l Colonial superb Quality Year- brick. 4 bedrmg., 2 rec. rm.. 1 rm.. HOMES i of det. brick gar. TA. kit. and bath: $75.80 mo. JU. at Apt. 1, 1301 Abingdon drive. 'round air-conditioning, library and Eves.. 9-1699 9-3490; after 6. LO 5-4800. —2 Alexandria. ¦¦¦¦¦¦¦¦ HOUSES WANTED TO RENT lavatory on Ist floor: four twin- or TU. 2-6194. DE LI'XE 2 BEDROOM APIS . -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School -

66-037-41 Forbes House 4811 Harvard Road College Park, Prince George’S County, Maryland C

CAPSULE SUMMARY PG: 66-037-41 Forbes House 4811 Harvard Road College Park, Prince George’s County, Maryland c. 1949 Private The Lustron at 4811 Harvard Road, College Park, Maryland, is significant for its architectural and engineering contributions. Closely associated with federally subsidized efforts to alleviate the post World War II housing shortage, the Lustron is integral to the history of housing in the United States. Although not widely implemented, Lustrons contribute to the post war development of the residential landscape funded primarily through government programs. As such, they are part of a long history of federally subsidized housing efforts, although characterized by innovations that seem remarkably daring in the context of federal housing programs—particularly given the strength of the forestry and conventional homebuilding industry. Further, the Lustron is significant for its contributions to prefabricated metal housing technology of the era as the manufacturing techniques utilized assembly line production directly influenced by the automobile industry. Porcelain-enameled steel panels were an innovative advancement for prefabricated housing construction, particularly as utilized in the single-floor modern ranch house plan that provides the Lustron with their unusual appearance. Their failure to capture a viable market is attributable perhaps to a nation that was truly ill-prepared to embrace modernity within the dearly-held institution of the house. The Forbes House retains sufficient integrity to convey its significance as a Lustron house constructed in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C. in the post World War II era. Constructed circa 1949, this one-story dwelling is the two-bedroom, Deluxe Westchester model produced by the Lustron Company in Columbus, Ohio. -

The Evolution of Architecture Faculty Organizational Culture at the University of Michigan Linda Mills

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations Graduate Capstone Projects 2018 The evolution of architecture faculty organizational culture at the University of Michigan Linda Mills Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.emich.edu/theses Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, and the Higher Education Administration Commons Recommended Citation Mills, Linda, "The ve olution of architecture faculty organizational culture at the University of Michigan" (2018). Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations. 933. https://commons.emich.edu/theses/933 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Graduate Capstone Projects at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: ARCHITECTURE FACULTY ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE The Evolution of Architecture Faculty Organizational Culture at the University of Michigan by Linda Mills Dissertation Eastern Michigan University Submitted to the Department of Leadership and Counseling Eastern Michigan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Educational Leadership Dissertation Committee: Ronald Flowers, Ed.D. Chair Jaclynn Tracy, Ph.D. Raul Leon, Ph.D. Russell Olwell, Ph.D. September 27, 2018 Ypsilanti, Michigan ARCHITECTURE FACULTY ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE ii Dedication This research is dedicated to all of the non-academic staff at the University of Michigan, at-will employees, who are working to support the work of faculty who operate with different norms, values and operating paradigms, protected by tenure, and unaware of the cognitive dissonance that exists between their operating worlds and ours. -

Historic Context and Survey of Post-World War II Residential Architecture Boulder, Colorado FINAL

Historic Context and Survey of Post-World War II Residential Architecture Boulder, Colorado FINAL Prepared for the City of Boulder, Colorado In association with the State Historical Fund Colorado Historical Society By Jennifer Bryant and Carrie Schomig TEC Inc. April 2010 Historic Context and Survey of Post-World War II Residential Architecture, Boulder, Colorado FUNDING AND PARTICIPANTS Prepared for the Funded by State Historic Fund Grant City of Boulder Project #08-01-007 Community Planning and Sustainability Department Historic Preservation Program The Colorado Historical Society’s State Boulder, CO 80306 Historical Fund (SHF) was created by the 1990 James Hewat, Historic Preservation Planner Colorado constitutional amendment allowing 303-441-3207 limited gaming in the towns of Cripple Creek, Central City, and Black Hawk. The amendment Prepared by directs that a portion of the gaming tax Jennifer Bryant, M.A., Historian revenues be used to promote historic Carrie Schomig, M.Arh., Architectural Historian preservation throughout the state. Funds are TEC Inc. distributed through a competitive grant 1658 Cole Boulevard, Suite 190 process, and all projects must demonstrate Golden, Colorado 80401 strong public benefit and community support. The City of Boulder, Historic Preservation State Historical Fund Coordinator Program has been awarded a SHF grant to Elizabeth Blackwell develop a historic context related to the theme Historic Preservation Specialist of post-World War II residential architecture in State Historical Fund the City of Boulder. Colorado Historical Society State Survey Project Coordinator Mary Therese Anstey Historical and Architectural Survey Coordinator Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation Colorado Historical Society 225 East 16th Avenue, Suite 950 Denver, CO 80203 Cover: This circa (ca.) 1953-1956 photograph shows the Edgewood subdivision in north-central Boulder, looking northwest. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Submissions

CULTURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT Information for Parks, Federal Agencies, Indian Tribes, States, Local Governments, and the Private Sector VOLUME 19 NO. 9 1996 CRM SUPPLEMENT National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Submissions he National Register of Historic California, or Usonian Houses by Frank Lloyd Places has been accepting multiple Wright, 1945-1960, in Iowa, contain valuable infor property nominations since 1977. mation that can be used in other states. To date, over one third of the Many cover documents are worthy of publica 66,300 National Register listings tion. The National Park Service encourages nominat are parTt of multiple property submissions. The ing authorities and others to seek ways to have them National Register multiple property nomination is published for scholars and the public to use. The designed to be a flexible tool for recording written information contained in them can also be used in statements of historic context and associated prop developing travel itineraries, World Wide Web sites, erty types and to provide a framework for evaluating for walking tours, interpretative projects, and other the significance of a related group of historic proper public education initiatives. ties. The statement of historic context is a written National Register Bulletin 16B: How to narrative that describes the unifying thematic frame Complete the National Register Multiple Property work; it must be developed in sufficient depth to Documentation Form (issued in 1991) explains in support the history, the relationships, and the detail how to nominate groups of related significant importance of the properties to be considered. A properties to the National Register. A video, The property type is a grouping of individual properties Multiple Property Approach, has been produced by characterized by common physical and/or associa the National Register. -

The Unveiling of a Statue to the Memory of Alexander R. Shepherd

F ins? THE SHEPHERD MEMORIAL The Unveiling of a Statue to the jHemorp of ^Ilexanber & ^ijepijerb in front of the District Building Washington, D. C. May 3, 1 909 Edited by WILLIAM VAN ZANDT COX for, the ^>ijcpfjerb jHemortal Committee -ioA.fttPuJIrkJU. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Order of Exercises 4 Introduction 7 Invocation by Rev. Dr. Wallace Radcliffe 11 Address by Chairman Theodore W. Noyes 13 Address by Mr. William F. Mattingly 23 Presentation of Statue by Mr. Brainard H. Warner 37 Acceptance by Commissioner Macfarland 39 Benediction by Right Rev. Alfred Harding 44 Shepherd Memorial Committee 45 Contributors to the Shepherd Memorial Fund 47 Financial Statement 51 ORDER OF EXERCISES Assembly Trumpeter, United States Marine Band Music— "America" United States Marine Band Invocation Rev. Wallace Radcliffe, D. D., LL. D. A Tribute—"Shepherd and the New Washington" Theodore W. Noyes Chairman Shepherd Memorial Committee, Presiding Music— "Some Day" — Wellings United States Marine Band Obligato by Arthur S. Whitcomb Address— "Shepherd and His Times" William F. Mattingly Unveiling of Statue By Alexander Robey Shepherd, 3d Salute First Battery Field Artillery, District of Columbia Militia Music— "The Star-Spangled Banner" United States Marine Band Presentation of Statue to the District of Columbia Brainard H. Warner Chairman Shepherd Memorial Finance Committee Acceptance of Statue Henry B. F. Macfarland President Board of Commissioners, District of Columbia Presentation of the Sculptor, U. S. J. Dunbar Music— March, "Gate City"— Weldon United States Marine Band Benediction Right Rev. Alfred Harding, Bishop of Washington Music under the direction of Lieut. W. H. Santelmann ALEXANDER R SHEPHERD aiexanber &.