38882 Exp03.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olympic Rowing Regatta Beijing, China 9-17 August

2008 Olympic Rowing Regatta Beijing, China 9-17 August MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTEnts 1. Introduction 3 2. FISA 5 2.1. What is FISA? 5 2.2. FISA contacts 6 3. Rowing at the Olympics 7 3.1. History 7 3.2. Olympic boat classes 7 3.3. How to Row 9 3.4. A Short Glossary of Rowing Terms 10 3.5. Key Rowing References 11 4. Olympic Rowing Regatta 2008 13 4.1. Olympic Qualified Boats 13 4.2. Olympic Competition Description 14 5. Athletes 16 5.1. Top 10 16 5.2. Olympic Profiles 18 6. Historical Results: Olympic Games 27 6.1. Olympic Games 1900-2004 27 7. Historical Results: World Rowing Championships 38 7.1. World Rowing Championships 2001-2003, 2005-2007 (current Olympic boat classes) 38 8. Historical Results: Rowing World Cup Results 2005-2008 44 8.1. Current Olympic boat classes 44 9. Statistics 54 9.1. Olympic Games 54 9.1.1. All Time NOC Medal Table 54 9.1.2. All Time Olympic Multi Medallists 55 9.1.3. All Time NOC Medal Table per event (current Olympic boat classes only) 58 9.2. World Rowing Championships 63 9.2.1. All Time NF Medal Table 63 9.2.2. All Time NF Medal Table per event 64 9.3. Rowing World Cup 2005-2008 70 9.3.1. Rowing World Cup Medal Tables per year 2005-2008 70 9.3.2. All Time Rowing World Cup Medal Tables per event 2005-2008 (current Olympic boat classes) 72 9.4. -

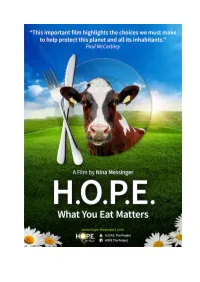

HOPE PRESSKIT.Pdf

H.O.P.E. What You Eat Matters A Film by Nina Messinger Documentary. Austria 2017. Running Time: 92 minutes. Language: English (with subtitles). Frame Rate: 25 fps. Shooting Format: HD. Sound: Dolby Digital 5.1, Stereo 2.0. www.hope-theproject.com H.O.P.E. What You Eat Matters I Press Kit SYNOPSIS (short) Obesity, allergies, diabetes, heart disease, or cancer: More than half of all people living in the industrialized world suffer from chronic diseases. Animals are reared for our consumption under abysmal conditions. Industrial-size livestock breeding facilities contribute to world hunger and the destruction of our natural environment and climate. The documentary H.O.P.E. shows how simply changing what we put on our plates and moving towards a plant-based diet can restore our body´s health and our planet´s balance. It has a clear message: By changing our eating habits, we can change the world! (long) Half of the population in Western society suffers from being overweight. Cardio- vascular diseases, diabetes and cancer are epidemic. Our meat consumption has quintupled over the past 50 years. 65 billion land animals are being slaughtered every year for food consumption. One third of the global grain production is fed to animals for fattening while 1.8 billion people worldwide suffer from hunger and starvation. Can there really be a solution to all these problems? It was the search for an answer to this question that led Austrian author and filmmaker Nina Messinger on a journey through Europe, India and the US to investigate the consequences of our diet and to meet with leading experts in nutrition, medicine, science, and agriculture, as well as with farmers and people who have recovered from severe illnesses by simply changing their eating habits. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 117 230 Relating to Racism, Blacks

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 117 230 ID015 623 TITLE A Selected Annotated Bibliography of .Material Relating to Racism, Blacks, Chicanos, Native Americans and Multi-Ethnicity. Vol-. 2. INSTITUTION Michigan Education Association, East Lansing. iv.'of Minority Affairs. PUB DATE 73 , NOTE 105p.; For volumes 1, 3, and 4; see ED 069 445, VD 015 624 and UD 015 718 respectively EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$5.70 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; *American Indians; *Annotated Bibliographies; Cultural Background; Cultural Factors; Ethnic'Groups; Ethnic Origins;, Ethnic Status Films; .Filmstrips; Instructional MaterialsC*Mexican Americans; *Negroes; Negro fiistory; Race'Relations; Racial Discrimination; Racial Factors; *Racism; Tape Recordings IDENTIFIERS Third World ABSTRACT The' second in the series, this selected annotated hihliography deals with new and recently discovered materials that address racism, BlackS, Chicanos,'native Americans, and multi - ethnicity. This bibliography is considered to be not all . inclusive but to reflect only on that material which,is considered to be most representative of the realities that relate to the involvemeiA and contributions of Third World groupS in'the development of the United States, and the climate of the times during which such involvement and contributions ocdurred.,Listing of materials usable at the elementary level are increased over those in Volume I. Contents deal with racism, including printed.materials, film, filmstrips, records and tapes; Black materials, including printed matter, films and filmstrips; Latino materials, including printed matter, films and filmstrips; native American materials, k. including printed matter, films and filmstrips; 'and multi-ethnic printed material. A list of Third World publishers is included. , (Author/AM) ********************************************************************* Documents acquired by ERIC include,many .informal Unpublished * materials not available from other sources. -

Suburbanization Historic Context and Survey Methodology

INTRODUCTION The geographical area for this project is Maryland’s 42-mile section of the I-95/I- 495 Capital Beltway. The historic context was developed for applicability in the broad area encompassed within the Beltway. The survey of historic resources was applied to a more limited corridor along I-495, where resources abutting the Beltway ranged from neighborhoods of simple Cape Cods to large-scale Colonial Revival neighborhoods. The process of preparing this Suburbanization Context consisted of: • conducting an initial reconnaissance survey to establish the extant resources in the project area; • developing a history of suburbanization, including a study of community design in the suburbs and building patterns within them; • defining and delineating anticipated suburban property types; • developing a framework for evaluating their significance; • proposing a survey methodology tailored to these property types; • and conducting a survey and National Register evaluation of resources within the limited corridor along I-495. The historic context was planned and executed according to the following goals: • to briefly cover the trends which influenced suburbanization throughout the United States and to illustrate examples which highlight the trends; • to present more detail in statewide trends, which focused on Baltimore as the primary area of earliest and typical suburban growth within the state; • and, to focus at a more detailed level on the local suburbanization development trends in the Washington, D.C. suburbs, particularly the Maryland counties of Montgomery and Prince George’s. Although related to transportation routes such as railroad lines, trolley lines, and highways and freeways, the location and layout of Washington’s suburbs were influenced by the special nature of the Capital city and its dependence on a growing bureaucracy and not the typical urban industrial base. -

Caldwell Esselstyn, M.D

Experts to Follow Caldwell Esselstyn, M.D. ʺDr. Esselstyn is a physician, author and former Olympic rowing champion. He is the author of Prevent and Reverse Heart Disease in which he demonstrates the benefits of a whole- foods, plant-based diet.ʺ To learn more about Dr. Esselstynʹs amazing work visit his website at http://www.dresselstyn.com/ Caldwell B. Esselstyn, Jr., received his B.A. from Yale University and his M.D. from Western Reserve University. In 1956, pulling the No. 6 oar as a member of the victorious United States rowing team, he was awarded a gold medal at the Olympic Games. He was trained as a surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic and at St. Georgeʹs Hospital in London. In 1968, as an Army surgeon in Vietnam, he was awarded the Bronze Star. Dr. Esselstyn has been associated with the Cleveland Clinic since 1968. During that time, he has served as President of the Staff and as a member of the Board of Governors. He chaired the Clinicʹs Breast Cancer Task Force and headed its Section of Thyroid and Parathyroid Surgery. He is a Fellow of the American College of Cardiology. Website: https://www.pbhw.com 1 Email: [email protected] In 1991, Dr. Esselstyn served as President of the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons. That same year he organized the first National Conference on the Elimination of Coronary Artery Disease, which was held in Tucson, Arizona. In 1997, he chaired a follow-up conference, the Summit on Cholesterol and Coronary Disease, which brought together more than 500 physicians and health-care workers in Lake Buena Vista, Florida. -

Benjamin Spock and the Spock Papers at Syracuse University

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Fall 1987 Benjamin Spock and the Spock Papers at Syracuse University Robert S. Pickett Syracuse University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, and the Child Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Pickett, Robert S. "Benjamin Spock and the Spock Papers at Syracuse University." The Courier 22.2 (1987): 3-22. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXII, NUMBER 2, FALL 1987 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXII NUMBER TWO FALL 1987 Benjamin Spock and the Spock Papers at Syracuse University By Robert S. Pickett, Professor of Child and 3 Family Studies, Syracuse University Alistair Cooke: A Response to Granville Hicks' I Like America By Kathleen Manwaring, Syracuse University Library 23 "A Citizen of No Mean City": Jermain W. Loguen and the Antislavery Reputation of Syracuse By Milton C. Sernett, Associate Professor 33 of Afro,American Studies, Syracuse University Jan Maria Novotny and His Collection of Books on Economics By Michael Markowski, Syracuse University 57 William Martin Smallwood and the Smallwood Collection in Natural History at the Syracuse University Library By Eileen Snyder, Physics and Geology Librarian, 67 Syracuse University News of the Syracuse University Library and the Library Associates 95 Benjamin Spack and the Spack Papers at Syracuse University BY ROBERT S. -

Medicine, Sport and the Body: a Historical Perspective

Carter, Neil. "Notes." Medicine, Sport and the Body: A Historical Perspective. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. 205–248. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781849662062.0006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 11:28 UTC. Copyright © Neil Carter 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Notes Introduction 1 J.G.P. Williams (ed.), Sports Medicine (London: Edward Arnold, 1962). 2 J.G.P. Williams, Medical Aspects of Sport and Physical Fitness (London: Pergamon Press, 1965), pp. 91–5. Homosexuality was legalized in 1967. 3 James Pipkin, Sporting Lives: Metaphor and Myth in American Sports Autobiographies (London: University of Missouri Press, 2008), pp. 44–50. 4 Paula Radcliffe, Paula: My Story So Far (London: Simon & Schuster, 2004). 5 Roger Cooter and John Pickstone, ‘Introduction’ in Roger Cooter and John Pickstone (eds), Medicine in the Twentieth Century (Amsterdam: Harwood, 2000), p. xiii. 6 Barbara Keys, Globalizing Sport: National Rivalry and International Community in the 1930s (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2006), p. 9. 7 Richard Holt, Sport and the British: A Modern History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), p. 3. 8 Deborah Brunton, ‘Introduction’ in Deborah Brunton (ed.), Medicine Transformed: Health, Disease and Society in Europe, 1800–1930 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004), p. xiii. 9 Cooter and Pickstone, ‘Introduction’ in Cooter and Pickstone (eds), p. xiv. 10 Patricia Vertinsky, ‘What is Sports Medicine?’ Journal of Sport History , 34:1 (Spring 2007), p. -

A Portrait of Pediatric Leadership: Dr. Benjamin Spock

A portrait of pediatric leadership: Dr. Benjamin Spock Richard B. Gunderman Department of Radiology, Riley Hospital for Children Indiana University School of Medicine Indianapolis, USA Pediatric radiologists can turn to many sources for leadership guidance: programming and publications at professional meetings and journals, courses offered by hospitals and health systems, and degree programs in business and health administration. Yet one of the best sources of insight is right under our noses — predecessors in the field of pediatrics whose leadership has left an enduring imprint on our profession and patients. When it comes to sheer magnitude, no pediatrician in recent memory left a larger mark or offered more inspiration for leaders than Benjamin Spock. Spock and his book Born the eldest child of a New Haven, CT, attorney in 1903, Spock attended Yale University, where he rowed on the varsity crew team that won the gold medal at the 1924 Paris Olympics [1]. He then entered medical school at Yale, eventually transferring to Columbia University, where he graduated first in his class in 1929. He had married Jane Cheney in 1927, and the couple had two sons. Believing that the pediatricians of the day focused too much on physical development, Spock enrolled in the New York Psychoanalytic Institute while also practicing pediatrics in the city. In conjunction with a 1944–1946 tour of duty in the U.S. Naval Reserve Corps and with the assistance of his wife, Spock began working on his best known book, The Commonsense Book of Baby and Child Care [2, 3]. First published in 1946, the book became a breakaway bestseller. -

Syuabus December 7-11, 1988 San Francisco Hilton on Hilton Square Keynote Speakers: Jay Haley, Arnold Lazarus and Cloe' Madanes

Brief Therapy: Myths, Methods and Metaphors the fourth international congress on Ericksonlan Approaches to Hypnosis and Psychotherapy SyUabUS December 7-11, 1988 San Francisco Hilton on Hilton Square Keynote Speakers: Jay Haley, Arnold Lazarus and Cloe' Madanes ) SM Featured speakers: Daniel Araoz, joseph Barber, joel Bergman, Simon Budman, Gianfranco Cecchin, Nicholas Cummings, Steve de Shazer, Albert Ellis, Richard Fisch, Stephen Gilligan, David Gordon, Mary Goulding, james Gustafson, Carol Lankton, Stephen Lankton, Herbert Lustig, Ruth McClendon, William O'Hanlon, Peggy Papp, Erving Polster, Sidney Rosen, Ernest Rossi, Peter Sifneos, Hans Strupp, Kay Thompson, Paul Watzlawick, john Weakland, Michael Yapko, Jeffrey Zeig and members of the Erickson family. Sponsored by The Milton H. Erickson Foundation, Inc., Phoenix, Arizona Co-sponsored by The Departments of Psychiatry and Psychology, The Veterans Administration Medical Center, Martinez, California and The Department of Family Practice, University of California at Davis Organizer: Jeffrey K. Zeig Executive Director: Linda Carr McThrall '' Each person is a unique Individual. Hence, psychotherapy should be for., mutated to meet the uniqueness of the ' individual's needs, rather than tailoring the person to fit the Procrustean bed of a hypothetical theory of human behavior. '' Milton H. Erickson, M.D. Table of Contents 1988 International Congress Schedule Wednesday. 2 Thursday. 4 Friday. 6 Saturday .......... .. ~ ....................... : . 7 Sunday .................................................. -

Chapter 2 20Th Century

THE SPORT OF ROWING To the readers of www.Rowperfect.co.uk This is the seventh installment on draft. Your comments, suggestions, correc- www.Rowperfect.co.uk of the latest draft of tions, agreements, disagreements, additional the beginning of my coming new book. sources and illustrations, etc. will be an es- Many thanks again to Rebecca Caroe for sential contribution to what has always been making this possible. intended to be a joint project of the rowing community. Details about me and my book project You can email me anytime at: are available at www.rowingevolution.com. [email protected]. For seven years I have been researching and writing a four volume comprehensive histo- For a short time you can still access the ry of the sport of rowing with particular em- first six installments, which have been up- phasis on the evolution of technique. In dated thanks to feedback from readers like these last months before publication, I am you. Additional chapters for your review inviting all of you visitors to the British will continue to appear at regular intervals Rowperfect website to review the near-final on www.Rowperfect.co.uk. TThhee SSppoorrtt ooff RRoowwiinngg AA CCoommpprreehheennssiivvee HHiissttoorryy bbyy PPeetteerr MMaalllloorryy VVoolluummee II GGeenneessiiss ddrraafffttt mmaannuussccrriiippttt JJaannuuaarryy 22001111 TThhee SSppoorrtt ooff RRoowwiinngg AA CCoommpprreehheennssiivvee HHiissttoorryy bbyy PPeetteerr MMaalllloorryy ddrraafffttt mmaannuussccrriiippttt JJaannuuaarryy 22001111 VVoolluummee II GGeenneessiiss Part V British Rowing in the Olympics 247 THE SPORT OF ROWING 22. The Birth of the Modern Olympics Athens – Paris – St. Louis www.olympic.org Pierre de Coubertin During classical times, every four years www.rudergott.de the various city-states of Greece would set 1896 Olympic Games, Athens aside their differences and call truces in ongoing wars in order to meet in peace at Olympia for a festival of athletic and rowing. -

Zenker, Stephanie F., Ed. Books For

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 415 506 CS 216 144 AUTHOR Stover, Lois T., Ed.; Zenker, Stephanie F., Ed. TITLE Books for You: An Annotated Booklist for Senior High. Thirteenth Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-0368-5 ISSN ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 465p.; For the 1995 edition, see ED 384 916. Foreword by Chris Crutcher. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 03685: $16.95 members, $22.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC19 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Adolescents; Annotated Bibliographies; *Fiction; High School Students; High Schools; *Independent Reading; *Nonfiction; *Reading Interests; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Motivation; Recreational Reading; Thematic Approach IDENTIFIERS Multicultural Materials; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Designed to help teachers, students, and parents identify engaging and insightful books for young adults, this book presents annotations of over 1,400 books published between 1994 and 1996. The book begins with a foreword by young adult author, Chris Crutcher, a former reluctant high school reader, that discusses what books have meant to him. Annotations in the book are grouped by subject into 40 thematic chapters, including "Adventure and Survival"; "Animals and Pets"; "Classics"; "Death and Dying"; "Fantasy"; "Horror"; "Human Rights"; "Poetry and Drama"; "Romance"; "Science Fiction"; "War"; and "Westerns and the Old West." Annotations in the book provide full bibliographic information, a concise summary, notations identifying world literature, multicultural, and easy reading title, and notations about any awards the book has won. -

The Militant

Photo by Finer Part of throng that protested war at New York rally Nat'l Protest Hits Viet War; THE 2 0 ,0 0 0at Rallyin New York NEW YORK — The November broad coalition of some 80 antiwar The rally was co-chaired by MILITANT 5-8 Mobilization for Peace in Viet and community groups. A. J. Muste, chairman of the na Published in the Interest of the Working People nam was kicked off here with a The rally served to kick off the tional November 8 Mobilization, and Al Evanoff, an official of Dis huge rally Nov. 5, held just off weekend’s activities. These in Vol. 31 - No. 41 Monday, November 14, 1966 Price 10£ cluded mass leafleting at churches trict 65, AFL-CIO, and a member Times Square. Some 20,000 people and in communities on Sunday, of the administrative committee crowded onto Sixth Avenue from leafleting of GIs at various places of the Parade Committee. 40th to 42nd Sts., while others where they can be reached in the Speakers at the rally spoke out stood on 41st St. going toward city on Sunday night, mass leaf against the war in a militant way Broadway. leting throughout the city on Mon and almost all of them urged with Good Vote Is Indicated Many people came to the rally day and leafleting at the polls on drawal of U.S. forces from Viet as participants in feeder marches Tuesday. nam. organized by antiwar and com Tables were set up at various The speakers included: Ruth munity groups in various parts of Turner, a national officer of CORE; Ivanhoe Donaldson, New For Ala.